11.1. (Very) Brief Refresher of the Basics

Recall that it is important when proposing nucleophile-electrophile reactions to avoid violating the octet rule. For example, if a nucleophile is attacking an electrophile that already has a full octet, the electrophile will have to lose electrons to avoid having more than a full octet/valence. Most often this is done by breaking another bond at the same time the new bond is being formed. In some reactions this may result in a σ bond being broken and another group/atom being ejected from the molecule. Atoms or groups of atoms that are ejected as part of the reaction are called leaving groups.

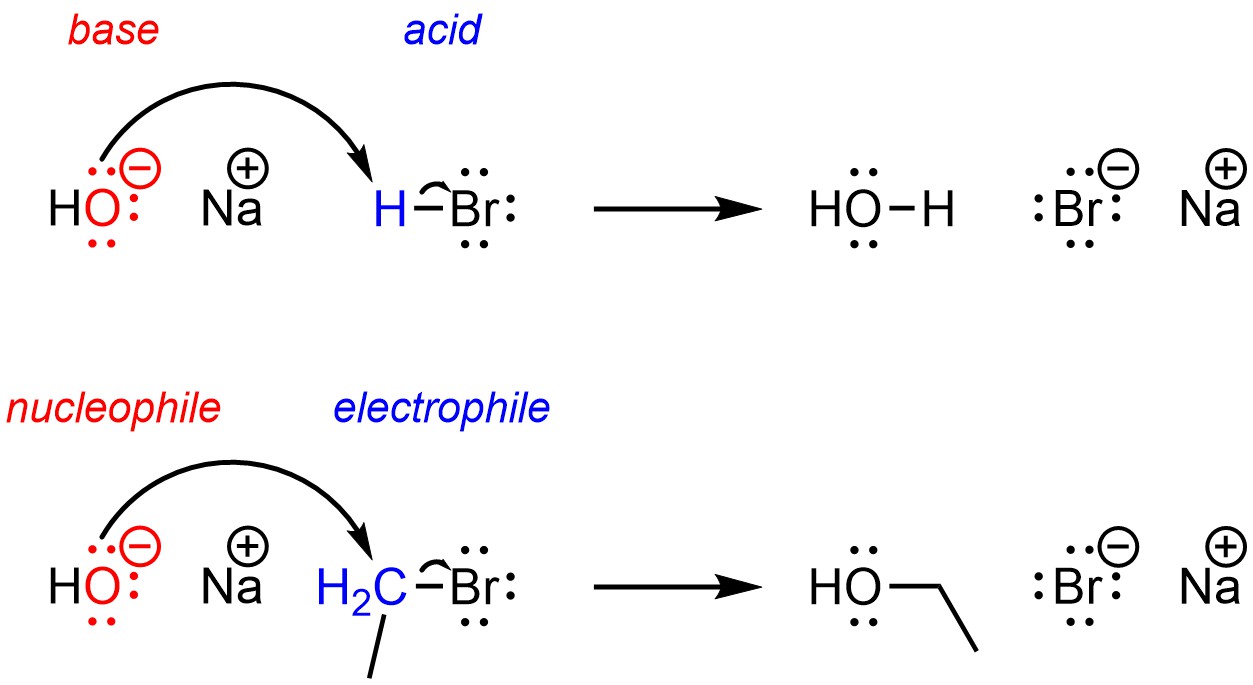

Recall that under the definitions of nucleophile and electrophile all Brønsted acid-base reactions are also nucleophile-electrophile reactions. The proton of the acid is electron-deficient and can be classed as an electrophile, while the base is electron-rich and can be classed as a nucleophile.

Nucleophilic substitution reactions are very similar to acid-base reactions (Scheme 11.1).

Scheme 11.1 – Comparison of an Acid-Base Reaction Mechanism with a Nucleophilic Substitution (SN2) Reaction Mechanism.

All nucleophilic substitution reactions follow one of two possible mechanisms. The goal of this chapter is to discuss the two possibilities and give enough context that students can determine which mechanism is followed for a given reaction.

There are many specifically named nucleophilic substitution reactions. For example, the formation of an ether by having an alkoxide attack an alkyl halide (see Scheme 11.8) is sometimes called Williamson Ether synthesis. This text will generally avoid using the specific names, but it is possible that they may be encountered in assignments, labs, discussions, etc. In these cases, searching the name of the reaction using a resource such as Wikipedia will be a straightforward way of understanding what is being discussed.