Chapter 10. Metamorphism and Metamorphic Rocks

Adapted by Karla Panchuk from Physical Geology by Steven Earle

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter and completing the review questions at the end, you should be able to:

- Summarize the factors that influence the nature of metamorphic rocks.

- Explain how foliation forms in metamorphic rocks.

- Classify metamorphic rocks based on their texture and mineral content, and explain the origins of both.

- Describe the various settings in which metamorphic rocks are formed and explain the links between plate tectonics and metamorphism

- Describe the different types of metamorphism, including burial metamorphism, regional metamorphism, seafloor metamorphism, subduction zone metamorphism, contact metamorphism, shock metamorphism, and dynamic metamorphism.

- Explain how metamorphic facies and index minerals are used to characterize metamorphism in a region.

- Explain why fluids are important for metamorphism and describe what happens during metasomatism.

Metamorphism Occurs Between Diagenesis And Melting

Metamorphism is the change that takes place within a body of rock as a result of it being subjected to high pressure and/or high temperature. The parent rock or protolith is the rock that exists before metamorphism starts. New metamorphic rocks can form from old ones as pressure and temperature progressively increase. The term parent rock is typically applied to the initial unmetamorphosed rock, rather than referring to each metamorphic rock that formed as metamorphism progresses. We don’t always know whether metamorphism occurred in an uninterrupted sequence or whether metamorphism stopped and started again for different reasons at different times.

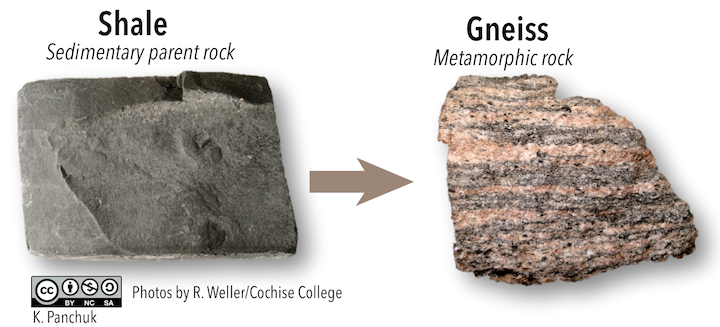

Metamorphic rocks form under pressures and temperatures that are higher than those experienced by sedimentary rocks during diagenesis, but at temperatures lower than those that cause igneous rocks to melt. Given that pressure and water content affect the temperature at which rocks melt, metamorphism can occur at higher temperatures for some kinds of rocks, whereas other rocks will begin to melt under these same conditions. Metamorphic rocks can have very different mineral assemblages and textures than their parent rocks (Figure 10.2), but their over-all chemical composition usually does not change very much.

Most metamorphism results from the burial of igneous, sedimentary, or pre-existing metamorphic rocks, to the point where they experience different pressures and temperatures than those at which they formed. Metamorphism can also take place if cold rock near the surface is intruded and heated by a hot igneous body. Metamorphism usually involves temperatures above 150°C, but some types of metamorphism do occur at temperatures lower than those at which the parent rock formed.