3.5 Isostasy

Lithospheric Plates Float on the Mantle

The mantle is able to convect because it can deform by flowing over very long timescales. This means that tectonic plates are floating on the mantle, like a raft floating in the water, rather than resting on the mantle like a raft sitting on the ground. How high the lithosphere floats will depend on the balance between gravity pulling the lithosphere down, and the force of buoyancy as the mantle resists the downward motion of the lithosphere. Isostasy is the state in which the force of gravity pulling the plate toward Earth’s centre is balanced by the resistance of the mantle to letting the plate sink.

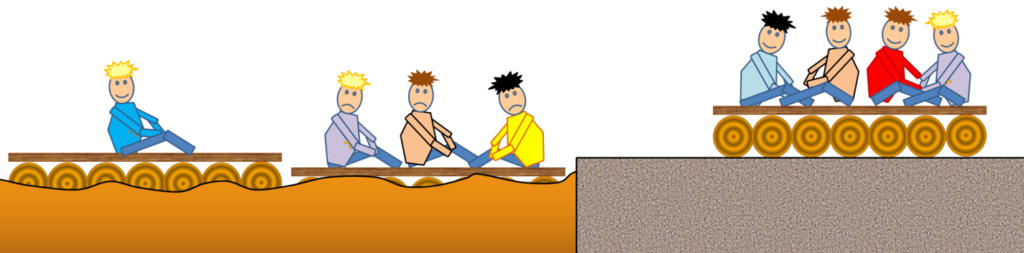

To see how isostasy works, consider the rafts in Figure 3.18. The raft on the right is sitting on solid concrete. The raft will remain at the same elevation whether there are two people on it, or four, because the concrete is too strong to deform. In contrast, isostasy is in play for the rafts on the left, which are floating in a swimming pool full of peanut butter. With only one person on board, the raft floats high in the peanut butter, but with three people, it sinks dangerously low. Peanut butter, rather than water, is used in this example because the viscosity of peanut butter (its stiffness or resistance to flowing) more closely represents the relationship between the tectonic plates and the mantle. Although peanut butter has a similar density to water, it’s higher viscosity means that if a person is added to a raft, it will take longer for the raft to settle lower into the peanut butter that it would take the raft to sink into water.

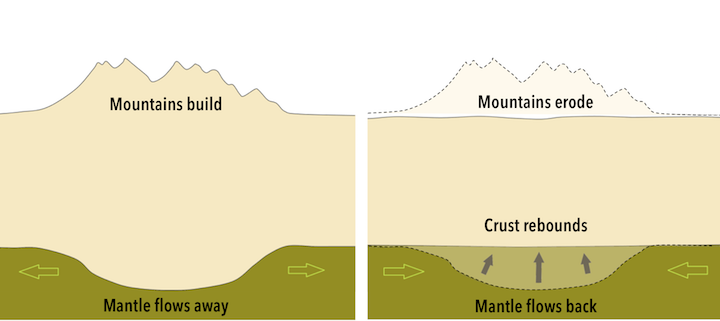

The relationship of Earth’s crust to the mantle is similar to the relationship of the rafts to the peanut butter. The raft with one person on it floats comfortably high. Even with three people on it the raft is less dense than the peanut butter, so it floats, but it floats uncomfortably low for those three people. The crust, with an average density of around 2.6 g/cm3, is less dense than the mantle (average density of ~3.4 g/cm3 near the surface, but more at depth), and so it is floating on the mantle. When weight is added to the crust through the process of mountain building, the crust slowly sinks deeper into the mantle, and the mantle material that was there is pushed aside (Figure 3.19, left). When erosion removes material from the mountains over tens of millions of years, decreasing the weight, the crust rebounds and the mantle rock flows back (Figure 3.19, right).

Isostasy and Glacial Rebound

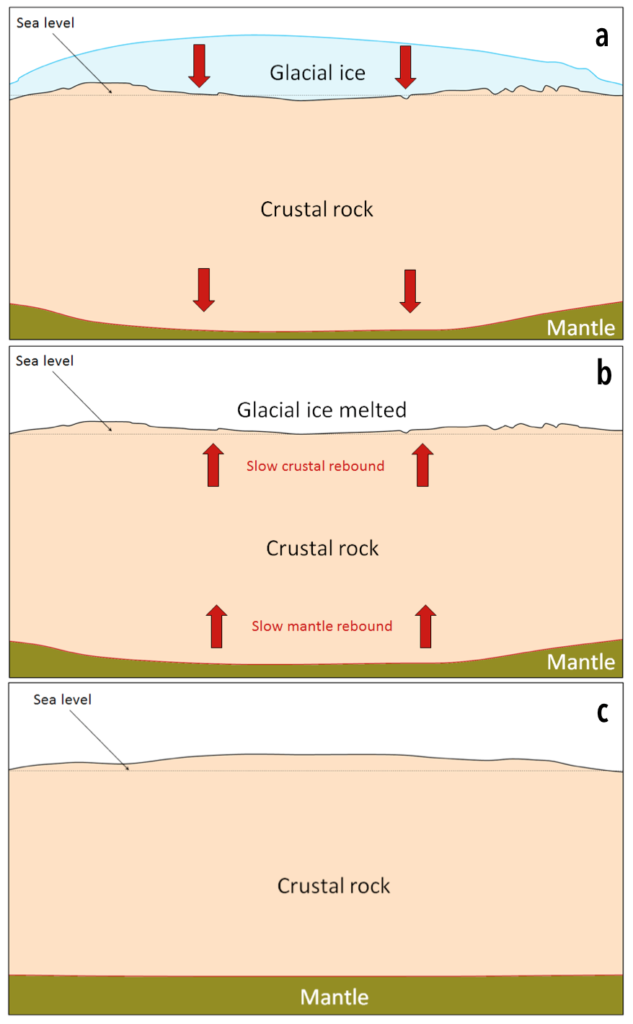

The crust and mantle respond in a similar way to glaciation. Thick accumulations of glacial ice add weight to the crust, and the crust subsides, pushing the mantle out of the way. The Greenland ice sheet, at over 2,500 m thick, has depressed the crust below sea level (Figure 3.20a). When the ice eventually melts, the crust and mantle will slowly rebound (Figure 3.20b), but full rebound will likely take more than 10,000 years (3.20c).

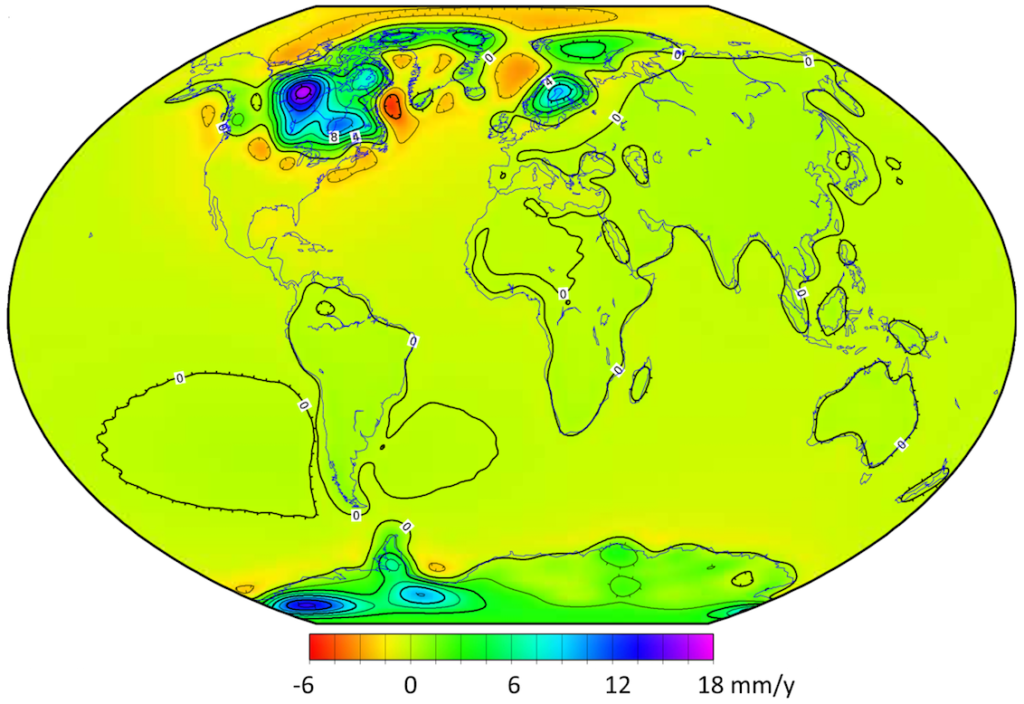

Large parts of Canada are still rebounding as a result of the loss of glacial ice over the past 12,000 years, as are other parts of the world (Figure 3.21). The highest rate of uplift is in a large area west of Hudson Bay, where the Laurentide Ice Sheet was the thickest, at over 3,000 m. Ice finally left this region around 8,000 years ago, and the crust is currently rebounding at nearly 2 cm/year. Strong isostatic rebound is also occurring in northern Europe where the Fenno-Scandian Ice Sheet was thickest, and in the eastern part of Antarctica, which also experienced significant ice loss during the Holocene.

Glacial rebound in one location means subsidence in surrounding areas (Figure 3.21, yellow through red regions). Regions surrounding the former Laurentide and Fenno-Scandian Ice Sheets that were lifted up when mantle rock was forced aside and beneath them are now subsiding as the mantle rock flows back.

How Can the Mantle Be Both Solid and Plastic?

You might be wondering how it is possible that Earth’s mantle is solid, rigid rock, and yet it convects and flows like a very viscous liquid. The explanation is that the mantle behaves as a non-Newtonian fluid, meaning that it responds differently to stresses depending on how quickly the stress is applied.

A good example of non-Newtonian behaviour is the deformation of Silly Putty, which can bounce when it is compressed rapidly when dropped, and will break if you pull on it sharply. But will deform in a liquid manner if stress is applied slowly. The force of gravity applied over a period of hours can cause it to deform like a liquid, dripping through a hole in a glass tabletop (Figure 3.22). Similarly, the mantle will flow when placed under the slow but steady stress of a growing (or melting) ice sheet.