2.1 Electric Flux

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Define the concept of flux

- Describe electric flux

- Calculate electric flux for a given situation

The concept of flux describes how much of something goes through a given area. More formally, it is the dot product of a vector field (in this chapter, the electric field) with an area. You may conceptualize the flux of an electric field as a measure of the number of electric field lines passing through an area (Figure 2.1.1). The larger the area, the more field lines go through it and, hence, the greater the flux; similarly, the stronger the electric field is (represented by a greater density of lines), the greater the flux. On the other hand, if the area rotated so that the plane is aligned with the field lines, none will pass through and there will be no flux.

(Figure 2.1.1) ![]()

A macroscopic analogy that might help you imagine this is to put a hula hoop in a flowing river. As you change the angle of the hoop relative to the direction of the current, more or less of the flow will go through the hoop. Similarly, the amount of flow through the hoop depends on the strength of the current and the size of the hoop. Again, flux is a general concept; we can also use it to describe the amount of sunlight hitting a solar panel or the amount of energy a telescope receives from a distant star, for example.

To quantify this idea, Figure 2.1.2(a) shows a planar surface ![]() of area

of area ![]() that is perpendicular to the uniform electric field

that is perpendicular to the uniform electric field ![]() . If

. If ![]() field lines pass through

field lines pass through ![]() , then we know from the definition of electric field lines (Electric Charges and Fields) that

, then we know from the definition of electric field lines (Electric Charges and Fields) that ![]() , or

, or ![]() .

.

The quantity ![]() is the electric flux through

is the electric flux through ![]() . We represent the electric flux through an open surface like

. We represent the electric flux through an open surface like ![]() by the symbol

by the symbol ![]() . Electric flux is a scalar quantity and has an SI unit of newton-meters squared per coulomb (

. Electric flux is a scalar quantity and has an SI unit of newton-meters squared per coulomb (![]() ). Notice that

). Notice that ![]() may also be written as

may also be written as ![]() , demonstrating that electric flux is a measure of the number of field lines crossing a surface.

, demonstrating that electric flux is a measure of the number of field lines crossing a surface.

(Figure 2.1.2) ![]()

of area

of area  is perpendicular to the electric field

is perpendicular to the electric field  .

.  field lines cross surface

field lines cross surface  . (b) A surface

. (b) A surface  of area

of area  whose projection onto the

whose projection onto the  -plane is

-plane is  . The same number of field lines cross each surface.

. The same number of field lines cross each surface.Now consider a planar surface that is not perpendicular to the field. How would we represent the electric flux? Figure 2.1.2(b) shows a surface ![]() of area

of area ![]() that is inclined at an angle

that is inclined at an angle ![]() to the

to the ![]() -plane and whose projection in that plane is

-plane and whose projection in that plane is ![]() (area

(area ![]() ). The areas are related by

). The areas are related by ![]() . Because the same number of field lines crosses both

. Because the same number of field lines crosses both ![]() and

and ![]() , the fluxes through both surfaces must be the same. The flux through

, the fluxes through both surfaces must be the same. The flux through ![]() is therefore

is therefore ![]() . Designating

. Designating ![]() as a unit vector normal to

as a unit vector normal to ![]() (see Figure 2.1.2(b)), we obtain

(see Figure 2.1.2(b)), we obtain

![]()

INTERACTIVE

Check out this video to observe what happens to the flux as the area changes in size and angle, or the electric field changes in strength.

Area Vector

For discussing the flux of a vector field, it is helpful to introduce an area vector ![]() . This allows us to write the last equation in a more compact form. What should the magnitude of the area vector be? What should the direction of the area vector be? What are the implications of how you answer the previous question?

. This allows us to write the last equation in a more compact form. What should the magnitude of the area vector be? What should the direction of the area vector be? What are the implications of how you answer the previous question?

The area vector of a flat surface of area ![]() has the following magnitude and direction:

has the following magnitude and direction:

- Magnitude is equal to area (

)

) - Direction is along the normal to the surface (

); that is, perpendicular to the surface.

); that is, perpendicular to the surface.

Since the normal to a flat surface can point in either direction from the surface, the direction of the area vector of an open surface needs to be chosen, as shown in Figure 2.1.3.

(Figure 2.1.3) ![]()

Since ![]() is a unit normal to a surface, it has two possible directions at every point on that surface (Figure 2.1.4(a)). For an open surface, we can use either direction, as long as we are consistent over the entire surface. Part (c) of the figure shows several cases.

is a unit normal to a surface, it has two possible directions at every point on that surface (Figure 2.1.4(a)). For an open surface, we can use either direction, as long as we are consistent over the entire surface. Part (c) of the figure shows several cases.

(Figure 2.1.4) ![]()

has been given a consistent set of normal vectors that allows us to define the flux through the surface.

has been given a consistent set of normal vectors that allows us to define the flux through the surface.However, if a surface is closed, then the surface encloses a volume. In that case, the direction of the normal vector at any point on the surface points from the inside to the outside. On a closed surface such as that of Figure 2.1.4(b), ![]() is chosen to be the outward normal at every point, to be consistent with the sign convention for electric charge.

is chosen to be the outward normal at every point, to be consistent with the sign convention for electric charge.

Electric Flux

Now that we have defined the area vector of a surface, we can define the electric flux of a uniform electric field through a flat area as the scalar product of the electric field and the area vector:

Figure 2.1.5 shows the electric field of an oppositely charged, parallel-plate system and an imaginary box between the plates. The electric field between the plates is uniform and points from the positive plate toward the negative plate. A calculation of the flux of this field through various faces of the box shows that the net flux through the box is zero. Why does the flux cancel out here?

(Figure 2.1.5) ![]()

) is negative, because

) is negative, because  is in the opposite direction to the normal to the surface. The electric flux through the top face (

is in the opposite direction to the normal to the surface. The electric flux through the top face ( ) is positive, because the electric field and the normal are in the same direction. The electric flux through the other faces is zero, since the electric field is perpendicular to the normal vectors of those faces. The net electric flux through the cube is the sum of fluxes through the six faces. Here, the net flux through the cube is equal to zero. The magnitude of the flux through rectangle

) is positive, because the electric field and the normal are in the same direction. The electric flux through the other faces is zero, since the electric field is perpendicular to the normal vectors of those faces. The net electric flux through the cube is the sum of fluxes through the six faces. Here, the net flux through the cube is equal to zero. The magnitude of the flux through rectangle  is equal to the magnitudes of the flux through both the top and bottom faces.

is equal to the magnitudes of the flux through both the top and bottom faces.The reason is that the sources of the electric field are outside the box. Therefore, if any electric field line enters the volume of the box, it must also exit somewhere on the surface because there is no charge inside for the lines to land on. Therefore, quite generally, electric flux through a closed surface is zero if there are no sources of electric field, whether positive or negative charges, inside the enclosed volume. In general, when field lines leave (or “flow out of”) a closed surface, ![]() is positive; when they enter (or “flow into”) the surface,

is positive; when they enter (or “flow into”) the surface, ![]() is negative.

is negative.

Any smooth, non-flat surface can be replaced by a collection of tiny, approximately flat surfaces, as shown in Figure 2.1.6. If we divide a surface S into small patches, then we notice that, as the patches become smaller, they can be approximated by flat surfaces. This is similar to the way we treat the surface of Earth as locally flat, even though we know that globally, it is approximately spherical.

(Figure 2.1.6) ![]()

To keep track of the patches, we can number them from 1 through ![]() . Now, we define the area vector for each patch as the area of the patch pointed in the direction of the normal. Let us denote the area vector for the

. Now, we define the area vector for each patch as the area of the patch pointed in the direction of the normal. Let us denote the area vector for the ![]() th patch by

th patch by ![]() . (We have used the symbol

. (We have used the symbol ![]() to remind us that the area is of an arbitrarily small patch.) With sufficiently small patches, we may approximate the electric field over any given patch as uniform. Let us denote the average electric field at the location of the

to remind us that the area is of an arbitrarily small patch.) With sufficiently small patches, we may approximate the electric field over any given patch as uniform. Let us denote the average electric field at the location of the ![]() th patch by

th patch by ![]() .

.

![]()

Therefore, we can write the electric flux ![]() through the area of the

through the area of the ![]() th patch as

th patch as

![]()

The flux through each of the individual patches can be constructed in this manner and then added to give us an estimate of the net flux through the entire surface ![]() , which we denote simply as

, which we denote simply as ![]() .

.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\Phi=\sum_{i=1}^{N}\Phi_i=\sum_{i=1}^{N}\vec{\mathbf{E}}_i\cdot\delta\vec{\mathbf{A}}_i~(N\mathrm{patch~estimate}).\]](https://openpress.usask.ca/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-56afbd5e1beeecdadfc5d348b877e016_l3.png)

This estimate of the flux gets better as we decrease the size of the patches. However, when you use smaller patches, you need more of them to cover the same surface. In the limit of infinitesimally small patches, they may be considered to have area ![]() and unit normal

and unit normal ![]() . Since the elements are infinitesimal, they may be assumed to be planar, and

. Since the elements are infinitesimal, they may be assumed to be planar, and ![]() may be taken as constant over any element. Then the flux

may be taken as constant over any element. Then the flux ![]() through an area

through an area ![]() is given by

is given by ![]() . It is positive when the angle between

. It is positive when the angle between ![]() and

and ![]() is less than

is less than ![]() and negative when the angle is greater than

and negative when the angle is greater than ![]() . The net flux is the sum of the infinitesimal flux elements over the entire surface. With infinitesimally small patches, you need infinitely many patches, and the limit of the sum becomes a surface integral. With

. The net flux is the sum of the infinitesimal flux elements over the entire surface. With infinitesimally small patches, you need infinitely many patches, and the limit of the sum becomes a surface integral. With ![]() representing the integral over

representing the integral over ![]() ,

,

In practical terms, surface integrals are computed by taking the antiderivatives of both dimensions defining the area, with the edges of the surface in question being the bounds of the integral.

To distinguish between the flux through an open surface like that of Figure 2.1.2 and the flux through a closed surface (one that completely bounds some volume), we represent flux through a closed surface by

where the circle through the integral symbol simply means that the surface is closed, and we are integrating over the entire thing. If you only integrate over a portion of a closed surface, that means you are treating a subset of it as an open surface.

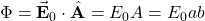

EXAMPLE 2.1.1

Flux of a Uniform Electric Field

A constant electric field of magnitude ![]() points in the direction of the positive

points in the direction of the positive ![]() -axis (Figure 2.1.7). What is the electric flux through a rectangle with sides

-axis (Figure 2.1.7). What is the electric flux through a rectangle with sides ![]() and

and ![]() in the (a)

in the (a) ![]() -plane and in the (b)

-plane and in the (b) ![]() -plane?

-plane?

(Figure 2.1.7) ![]()

through a rectangular surface.

through a rectangular surface.Strategy

Apply the definition of flux: ![]() , where the definition of dot product is crucial.

, where the definition of dot product is crucial.

Solution

- In this case,

.

. - Here, the direction of the area vector is either along the positive

-axis or toward the negative

-axis or toward the negative  -axis. Therefore, the scalar product of the electric field with the area vector is zero, giving zero flux.

-axis. Therefore, the scalar product of the electric field with the area vector is zero, giving zero flux.

Significance

The relative directions of the electric field and area can cause the flux through the area to be zero.

EXAMPLE 2.1.2

Flux of a Uniform Electric Field through a Closed Surface

A constant electric field of magnitude ![]() points in the direction of the positive

points in the direction of the positive ![]() -axis (Figure 2.1.8). What is the net electric flux through a cube?

-axis (Figure 2.1.8). What is the net electric flux through a cube?

(Figure 2.1.8) ![]()

through a closed cubic surface.

through a closed cubic surface.Strategy

Apply the definition of flux: ![]() , noting that a closed surface eliminates the ambiguity in the direction of the area vector.

, noting that a closed surface eliminates the ambiguity in the direction of the area vector.

Solution

Through the top face of the cube, ![]()

Through the bottom face of the cube, ![]() because the area vector here points downward.

because the area vector here points downward.

Along the other four sides, the direction of the area vector is perpendicular to the direction of the electric field. Therefore, the scalar product of the electric field with the area vector is zero, giving zero flux.

The net flux is ![]() .

.

Significance

The net flux of a uniform electric field through a closed surface is zero.

EXAMPLE 2.1.3

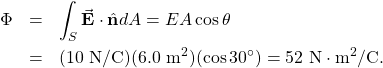

Electric Flux through a Plane, Integral Method

A uniform electric field ![]() of magnitude

of magnitude ![]() is directed parallel to the

is directed parallel to the ![]() -plane at

-plane at ![]() above the

above the ![]() -plane, as shown in Figure 2.1.9. What is the electric flux through the plane surface of area

-plane, as shown in Figure 2.1.9. What is the electric flux through the plane surface of area ![]() located in the

located in the ![]() -plane? Assume that

-plane? Assume that ![]() points in the positive

points in the positive ![]() -direction.

-direction.

(Figure 2.1.9) ![]()

.

.Strategy

Apply ![]() , where the direction and magnitude of the electric field are constant.

, where the direction and magnitude of the electric field are constant.

Solution

The angle between the uniform electric field ![]() and the unit normal

and the unit normal ![]() to the planar surface is

to the planar surface is ![]() . Since both the direction and magnitude are constant,

. Since both the direction and magnitude are constant, ![]() comes outside the integral. All that is left is a surface integral over

comes outside the integral. All that is left is a surface integral over ![]() , which is

, which is ![]() . Therefore, using the open-surface equation, we find that the electric flux through the surface is

. Therefore, using the open-surface equation, we find that the electric flux through the surface is

Significance

Again, the relative directions of the field and the area matter, and the general equation with the integral will simplify to the simple dot product of area and electric field.

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 2.1

What angle should there be between the electric field and the surface shown in Figure 2.1.9 in the previous example so that no electric flux passes through the surface?

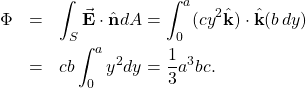

EXAMPLE 2.1.4

Inhomogeneous Electric Field

What is the total flux of the electric field ![]() through the rectangular surface shown in Figure 2.1.10?

through the rectangular surface shown in Figure 2.1.10?

(Figure 2.1.10) ![]()

Strategy

Apply ![]() . We assume that the unit normal

. We assume that the unit normal ![]() to the given surface points in the positive

to the given surface points in the positive ![]() -direction, so

-direction, so ![]() . Since the electric field is not uniform over the surface, it is necessary to divide the surface into infinitesimal strips along which

. Since the electric field is not uniform over the surface, it is necessary to divide the surface into infinitesimal strips along which ![]() is essentially constant. As shown in Figure 2.1.10, these strips are parallel to the x-axis, and each strip has an area

is essentially constant. As shown in Figure 2.1.10, these strips are parallel to the x-axis, and each strip has an area ![]() .

.

Solution

From the open surface integral, we find that the net flux through the rectangular surface is

Significance

For a non-constant electric field, the integral method is required.

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 6.2

If the electric field in Example 2.1.4 is ![]() , what is the flux through the rectangular area?

, what is the flux through the rectangular area?

Candela Citations

- Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/7a0f9770-1c44-4acd-9920-1cd9a99f2a1e@8.1. Retrieved from: http://cnx.org/contents/7a0f9770-1c44-4acd-9920-1cd9a99f2a1e@8.1. License: CC BY: Attribution