Chapter 34: Delivery

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between visual delivery and verbal delivery

- Utilize specific techniques to enhance vocal delivery

- Describe the importance of nonverbal delivery in public speaking

- Highlight common non-verbal pitfalls

- Utilize specific techniques to enhance non-verbal delivery

Key Terms and Concepts

- visual delivery

- verbal delivery

- verbal communication

- nonverbal communication

- projection

- vocal enunciation

- rate

- vocal pauses

You’ve done the research. You’ve written the information down into an outline, and transferred all of that onto a 3×5 cue card using keywords. Now it’s finally time to practice.

By now, you should recognize that a presentation—like all communication—is more than just transferring information from one person to another. It’s all about how you communicate that information. Ultimately, your delivery is going to be a big part of that. More specifically, your visual delivery and verbal delivery will have a huge impact on how your message is received and the overall experience of your audience. Rather than a check-list of skillsets, we invite you to read these as a series of inter-related behaviors and practices.

Visual Delivery

Have you played charades? Many of you have likely “acted out” a person, place, or a thing for an audience, using only your body and no words. Charades, like many games, demonstrates the heightened or exaggerated use of nonverbal communication—through acting out, the game highlights how powerful this communication method can be.

When speaking, similar to charades, your job is to create a captivating experience for your audience that leads them to new information or to consider a new argument. Nonverbals provide an important part of that experience by accentuating your content and contributing to an aesthetic experience.

As we discussed earlier, public speaking is embodied, and your nonverbals are a key part of living and communicating in and through your body. Here are the nonverbals that we will discuss in this section:

- eye contact

- facial expressions

- attire

- gestures and hands

- feet and posture

- moving in the space

All of the above enhance your message and invite your audience to give their serious attention to it—and to you. Your credibility, your sincerity, and your knowledge of your speech become apparent through your nonverbal behaviors.

Eye Contact

Imagine bringing in two qualified applicants for a job opening that you were responsible to fill. Each applicant will sit directly across from you and three other colleagues who are assisting.

While answering questions, Applicant 1 never breaks eye contact with you. It’s likely that, as the interview progresses, you begin to feel uncomfortable, even threatened, and begin shifting your own eyes around the room awkwardly. When the applicant leaves, you finally take a deep breath but realize that you can’t remember anything the applicant said.

Applicant 2 enters and, unlike the first, looks down at their notes and never makes direct eye contact. As you try to focus on their answers, they seem so uncomfortable that you aren’t able to concentrate on the exchange.

Both approaches are common mistakes when integrating eye contact into a speech. We have likely all seen speakers who read their presentation from notes and never look up. It’s also common for a speaker to zoom in on one audience member (such as the teacher!) and never break their gaze.

The general rule is that 80% of your total speech time should be spent making eye contact with your audience. When you’re able to connect by using eye contact, you create a more intimate, trusting, and transparent experience.

It’s important to note that you want to establish genuine eye contact with your audience, and not “fake” eye contact. There have been a lot of techniques generated for “faking” eye contact, and none of them look natural. For example, these approaches aren’t great:

- Three points on the back wall – One technique says you can just pick three points on the back wall and look at each point. What ends up happening, though, is you look like you are staring off into space and your audience will spend the majority of your speech trying to figure out what you are looking at. This technique may work better for a larger audience, but in a more intimate space (such as the classroom), the audience is close enough to be suspicious. Put simply: we can tell you aren’t looking at us.

- The swimming method – This happens when someone is reading their speech and looks up quickly and briefly, not unlike a swimmer who pops their head out of the water for a breath before going back under. Eye contact is more than just physically moving your head; it is about looking at your audience and establishing a connection.

Instead, work to maintain approximately three seconds of eye contact with audience members throughout the room. You are, after all, speaking to them, so use your eyes to make contact. This approach may also reduce some anxiety because you can envision yourself speaking directly to one person at a time, rather than a room full of strangers.

Facial Expressions

Picture being out to dinner with a friend and, as you finish telling a story about a joke you played on your partner, you look up to a grimacing face.

“What?” you ask.

“Oh, nothing,” they reply. But their face says it all.

Realizing that their face has “spilled the beans” so to speak, your friend might correct their expression by shrugging and biting their lip—a move that may insinuate nervousness or anxiety. You perceive that they didn’t find your story as humorous as you’d hoped.

Facial expressions communicate to others (and audiences) in ways that are consistent or inconsistent with your message. In the example above, your friend’s feedback of “oh, nothing” was inconsistent with their facial expressions. Their words didn’t trump their facial expressions, however, and their nonverbal feedback was part of the communication.

In the context of your speech, your facial expressions will matter. Your audience will be looking at your face to guide them through the speech, so these expressions are an integral part of communicating meaning to your audience.

In fact, if your facial expressions seem inconsistent with or contradictory to the tone of the argument, an audience may go so far as to feel distrust toward you as a speaker. Children might, for example, say, “I’m fine” or “It doesn’t hurt” after falling and scraping their knee, but their face often communicates a level of discomfort. In this case, their facial expression is inconsistent with their verbal message. If you’re frowning while presenting information that the audience perceives to be positive, they may feel uneasy or unsure how to process that information. So, consistency can increase your ethos.

Similarly, your facial expressions, like the soundtrack of a movie or commercial, can assist in setting the aesthetic tone; they are part of developing pathos. Given the amount of information that we all encounter daily, including information about global injustices, it’s often insufficient to merely state the problem and how to solve it. Audience members need buy-in from you as the speaker. Using facial expressions to communicate emotions, for example, can demonstrate your commitment to and feelings about an issue.

To be clear, facial expressions, like other forms of nonverbal communication, can greatly impact an audience member’s perception of the speaker, but not all audiences may interpret your expressions the same.

Attire

What you wear can either enhance or detract from the audience’s experience. Like facial expressions, you want your attire to be consistent with the message that you’re delivering. Context is important here, since the purpose and audience will inform appropriate attire.

We recommend considering two questions when selecting your attire:

First, what attire matches the occasion? Is this a casual occasion? Does it warrant a more professional or business-casual approach? If you’re speaking at an organization’s rally, for example, you may decide to wear attire with the organization’s logo and jeans. Other occasions, such as a classroom or city council meeting, may require a higher level of professional attire.

Second, ask yourself, “have I selected any attire that could be distracting while I’m speaking?” Certain kinds of jewelry, for example, might make additional noise or move around your arm, and audiences can focus too much on the jewelry. In addition to noise-makers, some attire can have prints that might distract, including letters, wording, or pictures.

Your attire can influence how the audience perceives you as a speaker—that is, your credibility—which, as we’ve discussed, is key to influencing listeners.

Movement

When you (and your body) move, you communicate. You may, for example, have a friend who, when telling exciting stories, frantically gestures and paces the room—their movement is part of how they communicate their story. They likely do this unconsciously, and that’s often how much of our informal movement occurs.

Many of us, like your friend, have certain elements of movement that we comfortably integrate into our daily interactions. In order to determine how to integrate movements most effectively into your speech, ask yourself, “how can I utilize these movements (or put them in check) to enhance the audience’s experience?” In this section, we will introduce how and why movement should be purposefully integrated into your speech. We’ll focus on your hands and your feet, and consider how to move around the space.

Not sure what nonverbals you commonly use when communicating? Ask a friend! Your friends are observant, and they can likely tell you if you over-gesture, look down, stay poised, etc. Use this inventory to determine areas of focus for your speeches.

Gestures and Hands

Everyone who gives a speech in public gets scared or nervous. Even professionals who do this for a living feel that way, but they have learned how to combat those nerves through experience and practice. When we get scared or nervous, our bodies emit adrenaline into our systems so we can deal with whatever problem is causing us to feel that way. In a speech, that burst of adrenaline is going to try to work its way out of your body and manifest itself somehow. One of the main ways is through your hands.

Three common reactions to this adrenaline rush are:

- Jazz hands! It may sound funny, but nervous speakers can unknowingly incorporate “jazz hands”—shaking your hands at your sides with fingers opened wide—at various points in their speech. While certainly an extreme example, this and behaviors like it can easily becoming distracting.

- Stiff as a board. At the other end of the scale, people who don’t know what to do with their hands or use them “too little” sometimes hold their arms stiffly at their sides, behind their backs, or in their pockets, all of which can also look unnatural and distracting.

- Hold on for dear life! Finally, some speakers might grip their notes or a podium tightly with their hands. This tendency might also result in tapping on a podium, table, or another object nearby.

It’s important to remember that just because you aren’t sure what your hands are doing does not mean they aren’t doing something. Fidgeting, making jazz hands, gripping the podium, or keeping hands in pockets are all common and result in speakers asking, “did I really do that? I don’t even remember!”

Are you someone who uses gestures when speaking? If so, great! Use your natural gestures to create purposeful aesthetic emphasis for your audience. If you were standing around talking to your friends and wanted to list three reasons why you should all take a road trip this weekend, you would probably hold up your fingers as you counted off the reasons (“First, we hardly ever get this opportunity. Second, we can…”). Try to pay attention to what you do with your hands in regular conversations and incorporate that into your delivery. Be conscious, though, of being over the top and gesturing at every other word. Remember that gestures highlight and punctuate information for the audience, so too many gestures (like jazz hands) can be distracting.

Similarly, are you someone who generally rests your arms at your sides? That’s OK, too! Work to keep a natural (and not stiff) look, but challenge yourself to integrate a few additional gestures throughout the speech.

Feet and Posture

Just as it does through your hands, nervous energy might try to work its way out of your body through your feet. Common difficulties include:

- The side-to-side. You may feel awkward standing without a podium and try to shift your weight back and forth. On the “too much” end, this is most common when people start “dancing” or stepping side to side.

- The twisty-leg. Another variation is twisting feet around each other or the lower leg.

- Stiff-as-a-board. On the other end are speakers who put their feet together, lock their knees, and never move from that position. Locked knees can restrict oxygen to your brain, so there are many reasons to avoid this difficulty.

These options look unnatural, and therefore will prove to be distracting to your audience.

The default position for your feet, then, is to have them shoulder-width apart, with your knees slightly bent. Since public speaking often results in some degree of physical exertion, you need to treat speaking as a physical activity. Public speaking is, after all, a full body experience. Being in-tune and attuned to your body will allow you to speak in a way that’s both comfortable for you and the audience.

In addition to keeping your feet shoulder-width apart, you’ll also want to focus on your posture. By focusing on good posture over time, it will eventually become habitual.

Moving in the Space

We know that you’re likely wondering, “Should I do any other movement around the room?”

Unfortunately, there isn’t an easy answer. Movement depends on two overarching considerations:

1) What’s the space?

2) What’s the message?

First, movement is always informed by the space in which you’ll speak. Consider the two following examples:

- You’ll be a giving a presentation at a university where a podium is set up with a stable microphone.

- You’re speaking at a local TedTalk event with an open stage.

Both scenarios provide constraints and opportunities for movement.

In the university space, you must stay planted behind the microphone to guarantee sound. While somewhat constraining, this setup does allow a stable location to place your notes and a microphone to assist in projecting, and it allows you to focus on other verbal and nonverbal techniques.

In the TedTalk example, you are not constrained by a stable microphone and you have a stage for bodily movement. The open stage means that the entire space becomes part of the aesthetic experience for the audience. However, if you are less comfortable with movement, the open space may feel intimidating because audiences may assume that you’ll use the entire space.

Once you have knowledge of the speaking space and speech content, you can start using movement to add dimension to the aesthetic experience for your audience.

One benefit of movement is that it allows you to engage with different sections of the audience. If you are not constrained to one spot (in the case of a podium or a seat, for example), then you are able to use movement to engage with the audience by adjusting your spatial dynamic. You can literally move your body to different sides of the stage and audience. Such a use of space enables each side of a room to be pulled in to the content because you close the physical distance and create clear pathways for eye contact.

Without these changes, sections of the audience may feel lost or forgotten. Consider your role as a student. Have you experienced a professor or teacher who stays solitary and does not move to different sides of the room? It can be difficult to stay motivated to listen or take notes if a speaker is dominating one area of the space.

Changing the spatial dynamics goes beyond moving from side-to-side. You can also move forward and backward. This allows you to move closer to the audience or back away depending on what experience you’re trying to create.

In addition to engaging with the audience, movement often signals a transition between ideas or an attempt to visually enunciate an important component of your information. You may want to signal a change in time or mark progression. If you’re walking your audience through information chronologically, movement can mark that temporal progression where your body becomes the visual marker of time passing.

When you speak, moving in the space can be beneficial. As you plan your purposeful movement, be aware of the message you’re providing and the space in which you’re speaking.

Verbal Delivery

Humans are communicators. We rely on communication processes to make sense of our world, and we rely on others’ communicating with us to create shared meaning. Through symbols, we use and adapt language with one another and our communities.

The same is true for speeches, but what symbols you select and how you portray them—what we’ll call verbal delivery— are dependent on your audience and how they experience or comprehend what you say.

For example, consider your favorite podcaster or podcast series. We love crime podcasts! Despite being reliant on verbal delivery only, the presenters’ voices paint an aesthetic picture as they walk us through stories around crime, murder, and betrayal. So, how do they do it? What keeps millions of people listening to podcasts and returning to their favorite verbal-only speakers? Is it how they say it? Is it the language they choose? All of these are important parts of effective verbal delivery.

Below, we begin discussing verbal delivery, looking at the following topics:

- projection

- vocal enunciation

- rate

- vocal pauses

Projection

“Louder!”

You may have experienced a situation where an audience notified a speaker that they couldn’t be heard. “Louder!” Here, the audience is letting the speaker know to increase their volume, or the relative softness or loudness of one’s voice. In this example, the speaker needed to more fully project their vocals to fit the speaking-event space by increasing their volume. In a more formal setting, however, an audience may be reluctant to give such candid feedback, so it is your job to prepare.

Projection is a strategy to vocally fill the space; thus, the space dictates which vocal elements need to be adapted because every person in the room should comfortably experience your vocal range. If you speak too softly (too little volume or not projecting), your audience will struggle to hear and understand and may give up trying to listen. If you speak with too much volume, your audience may feel that you are yelling at them, or at least feel uncomfortable with you shouting. The volume you use should fit the size of the audience and the room.

Vocal Enunciation

Vocal enunciation is often reduced to pronouncing words correctly, but enunciation also describes the expression of words and language.

Have you ever spoken to a friend who replied, “Stop that! You’re mumbling.” If so, they’re signaling to you that they aren’t able to understand your message. You may have pronounced the words correctly but had poorly enunciated the words, leading to reduced comprehension.

One technique to increase enunciation occurs during speech rehearsal, and it’s known as the “dash” strategy: e-nun-ci-ate e-ve–ry syll–a–bal in your pre-sen-ta-tion.

The dashes signify distinct enunciation to create emphasis and expression. However, don’t go overboard! The dash strategy is an exaggerated exercise, but it can lead to a choppy vocal delivery.

Instead, use the dash strategy to find areas where difficult and longer words need more punctuated emphasis and, through rehearsal, organically integrate those areas of emphasis into your presentational persona.

Rate

The rate is how quickly or slowly you say the words of your speech. A slower rate may communicate to the audience that you do not fully know the speech. “Where is this going?” they may wonder. It might also be slightly boring if the audience is processing information faster than it’s being presented.

By contrast, speaking too fast can be overly taxing on an audience’s ability to keep up with and digest what you are saying. It sometimes helps to imagine that your speech is a jog that you and your friends (the audience) are taking together. You (as the speaker) are setting the pace based on how quickly you speak. If you start sprinting, it may be too difficult for your audience to keep up and they may give up halfway through. Most people who speak very quickly know they speak quickly, and if that applies to you, just be sure to practice slowing down and writing yourself delivery cues in your notes to maintain a more comfortable rate.

You will want to maintain a good, deliberate rate at the beginning of your speech because your audience will be getting used to your voice. We have all called a business where the person answering the phone mumbles the name of the business in a rushed way. We aren’t sure if we called the right number. Since the introduction is designed to get the audience’s attention and arouse interest in your speech, you will want to focus on clear vocal rate here.

You might also consider varying the rate depending on the type of information being communicated. While you’ll want to be careful going too slow consistently, slowing your rate for a difficult piece of supporting material may be helpful. Similarly, quickening your rate in certainly segments can communicate an urgency.

Although the experience might seem awkward, watching yourself give a speech via recording (or web cam) is a great way to gauge your natural rate and pace.

Vocal Pauses

The common misconception for public speaking students is that pausing during your speech is bad, but vocal pauses can increase both the tone and comprehension of your argument. This is especially true if you are making a particularly important point or wanting a statement to have powerful impact: you will want to give the audience a moment to digest what you have said. You may also be providing new or technical information to an audience that needs additional time to absorb what you’re saying.

For example, consider the following statement:

Following a statement like this, you want to give your audience a brief moment to fully consider what you are saying.

Use audience nonverbal cues and feedback (and provide them as an audience member) to determine whether additional pauses may be necessary for audience comprehension. Audiences are generally reactive and will use facial expressions and body language to communicate if they are listening, if they are confused, angry, or supportive.

Of course, there is such a thing as pausing too much, both in terms of frequency and length. Someone who pauses too often may appear unprepared. Someone who pauses too long (more than a few seconds) runs the risk of the audience feeling uncomfortable or, even worse, becoming distracted or letting their attention wander.

Pauses should be controlled to maintain attention of the audience and to create additional areas of emphasis.

Key Takeaways

- How you communicate your speech—and how the audience interprets the information—will be depend on your visual delivery and verbal delivery.

- Your visual delivery will depend on the nonverbal elements of your speech, which include eye contact, facial expressions, attire, and movement.

- Your verbal delivery will depend on how you say the words themselves. Are you speaking loud enough? Clear enough? How fast are you speaking? Are you pausing enough to let your words resonate with audience? All of these things will impact how the audience interprets and retains what you say.

Attributions

This chapter is adapted from “Speak Out, Call In: Public Speaking as Advocacy” by Meggie Mapes (on Pressbooks). It is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

This chapter is also adapted from “Speak Out, Call In: Public Speaking as Advocacy” by Meggie Mapes (on Pressbooks). It is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

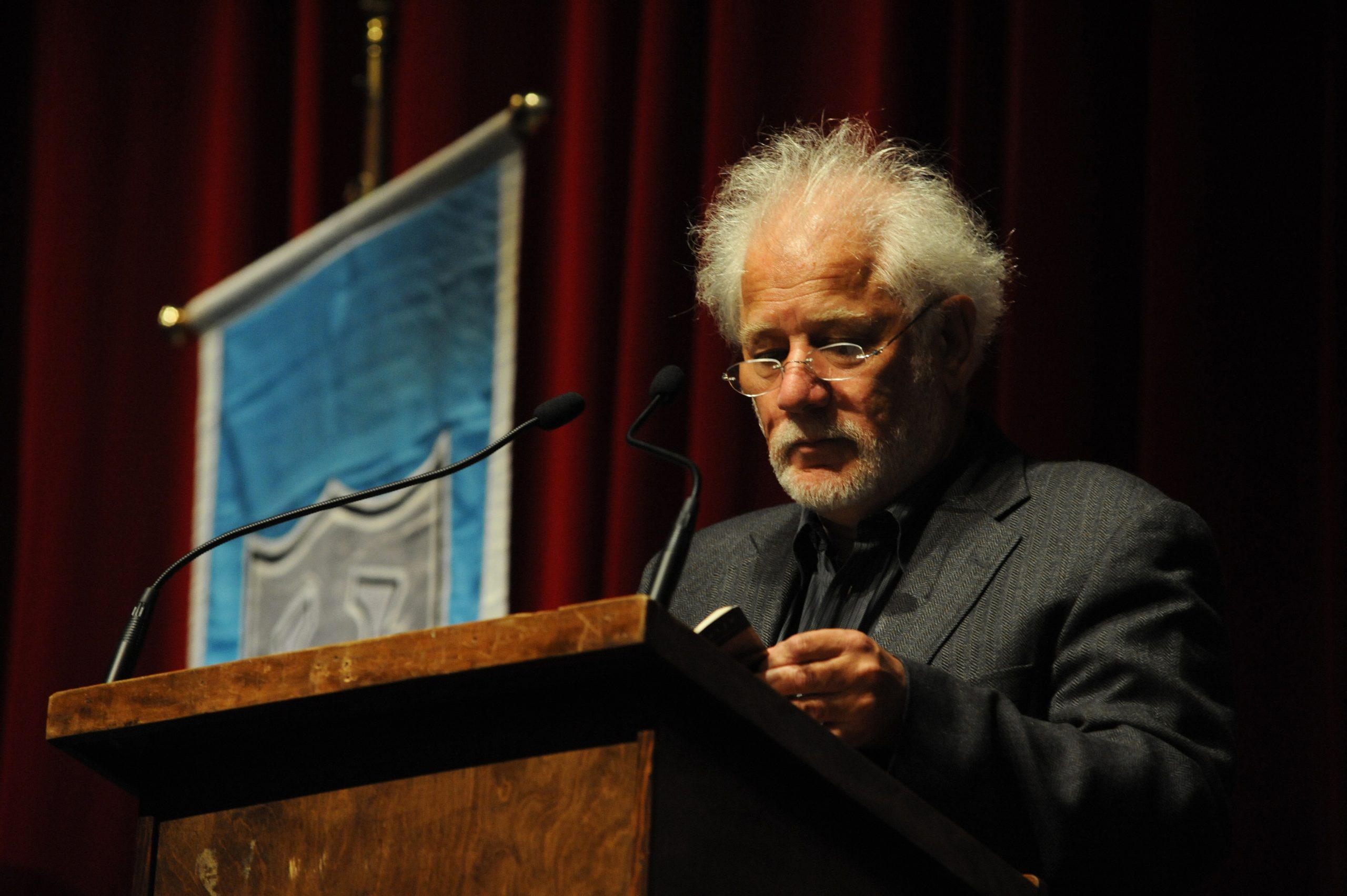

Image #1: “Michael Ondaatje Tualane Lecturn 2010” (on Wikimedia Commons) is used under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License

Image #2: “TED Talk Santa Barbara, CA” (on Wikimedia Commons) is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License

the way you use elements of nonverbal communication—eye contact, facial expressions, attire, and movement—to communicate your message

using your voice to communicate a message through projection, vocal enunciation and punctuation, pace and rate, and vocal pauses

the transfer of information through the use of body language including eye contact, facial expressions, gestures and more

the receiver or receivers of a message

a quality that allows others to trust and believe you

a rhetorical appeal that addresses the values of an audience as well as establishes authorial credibility/character

a rhetorical appeal that tries to tap into the audience's emotions to get them to agree with a claim

a technique for making your voice loud and clear that is more than just speaking loudly or shouting

a speaking technique where words are pronounced correctly and expressed in such a way that it draws in the audience

how quickly or slowly you speak during a presentation

a strategic pause during a presentation that gives your audience a chance to fully understand what has been said