Chapter 22: The Rhetorical Nature of Reports

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define what a report is and identify the different forms that it can take.

- Identify how certain reports can be informal, formal, or somewhere in-between.

- Explain how you have already created several reports during your academic career.

Key Terms and Concepts

- report

- written report

- oral report

- informative report

- persuasive report

Over the next several chapters, we will be walking you through the process of creating reports. Reports are crucial deliverables in many technical professions. In fact, engineers can spend anywhere from 20% to 95% of their time writing reports (Leydens, 2008). That’s a lot of writing! However, it’s also important to remember that not all reports are written, as they can take an oral format as well. Before we go into the actual process of how to write a report or give a presentation, however, let’s look at reports more generally.

What is a Report?

What comes to mind when you think of the word report? If you went to school in Canada, your first thought might be one of the many book reports you did for your English classes where you had to summarize and review a book you read recently. However, since you have been in this class for a couple weeks now, maybe you’re thinking about reports in a professional/technical sense, like a business proposal or a research statement.

Before we get too ahead of ourselves, let’s consider this definition for the word report:

That definition is pretty basic, but what that tells you is that reports are happening around you all the time because, as we’ve already learned, communication is the transmission of information. This also means that a report doesn’t just have to be written, since we also transmit information when we speak. Let’s look at a more detailed definition.

Something has changed with this definition. Can you see what it is? Similar to our first definition, this new definition also describes reports as an exchange of information. The difference, though, is that there is a focus on you—the writer or speaker—to share that information in a way that is accessible and relatable to your audience.

We’ll explain how to do that in just a moment, but let’s first review the different forms a report might take in your professional career, as well as some reports you may have already done (possibly even without realizing it).

Types of Reports

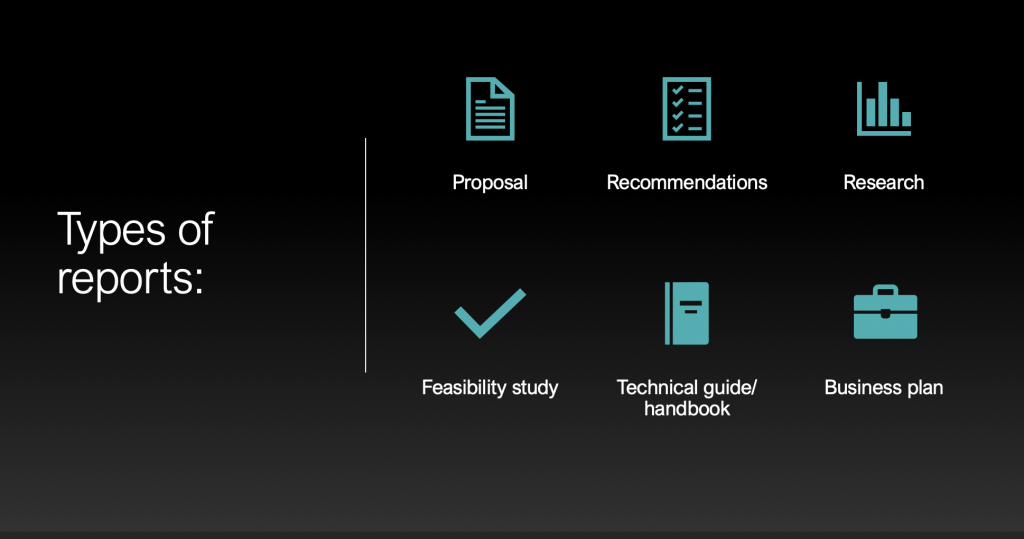

Reports can take different forms. Here are few different types:

Depending on your career trajectory, you may have to do a several, if not all, of these report types.

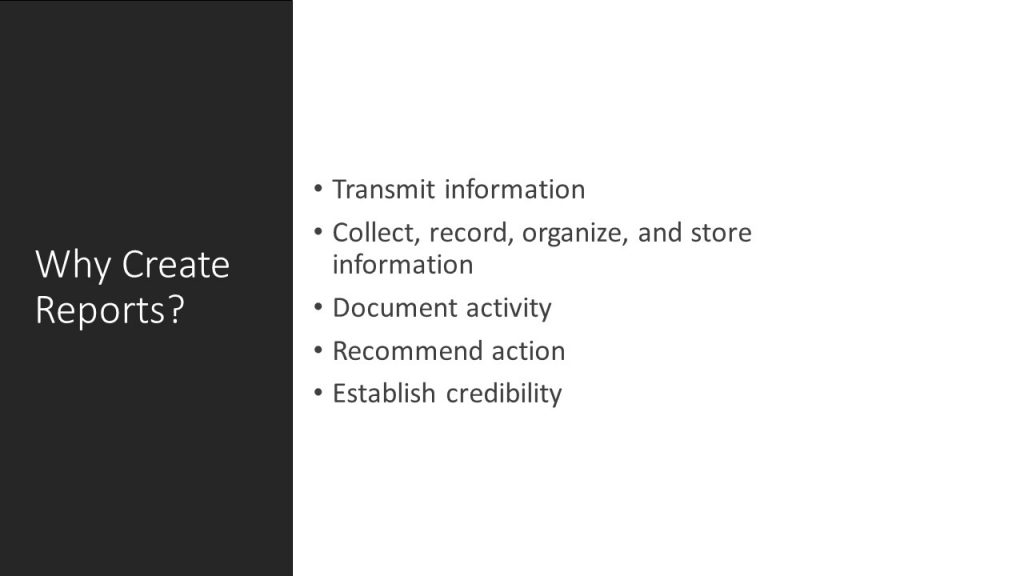

The reason why you may be writing or presenting a report will depend on your career and need. As a result, there are a number of different reasons why you would create one:

Do any of those reasons sound familiar? They should! At their core, reports are a form of rhetorical communication, which we covered in the first chapter. Not only are they intentional, purposeful acts of communication, but they also involve making a connection with the audience in order to get them to change something. You’ll need to accomplish both in the formal report and persuasive presentation you create for RCM 200.

Composing a report may seem a bit overwhelming, but it’s important to realize that you have already created several reports in your life. Of course, you may think, “That’s not true. The whole reason I’m taking the class is so I can learn how to do that!” Trust us when we say you have more experience with reports than you think.

Kinds of Reports

To help you see how you have already been creating reports in other contexts, it is important to distinguish between the two types of reports.

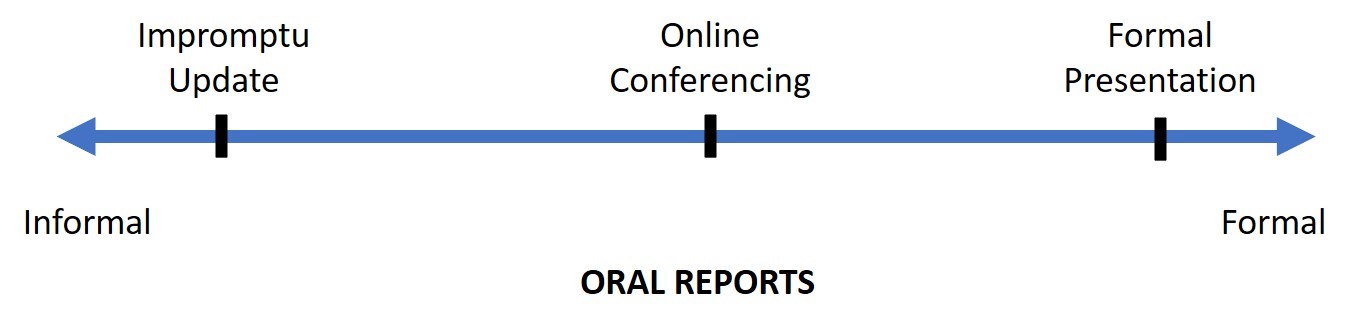

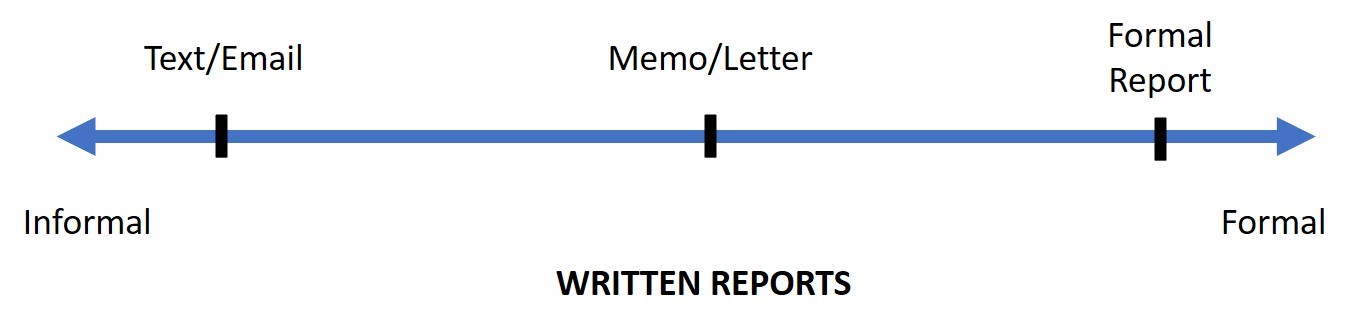

As we have mentioned, reports can be presented either orally or in writing. However, within those two categories are range of different forms that a report can take. Not only that, it’s important to recognize that reports can move on a spectrum from informal to formal.

Oral Reports

Can you think of any informal oral reports that you’ve done? Here is an example: if you meet with your team, and a colleague asks you about your portion of the research, you might tell them about some of the resources you have found and how you plan to use them. In this case, you would be providing an impromptu update. Does this sound familiar? If you bump into a friend in the hall and have a brief chat about your plans this weekend, this is also an impromptu update.

Online conferencing happens when you meet a supervisor, instructor, or team over a platform like Zoom or Webex. Usually, such meetings take place at a scheduled time, which means there are specific topics you need to discuss. It is far less casual than running into someone in the hallway. However, even an online conference can be less formal depending on the context. If you are video chatting with friends or family in another city, or province, or even country, odds are it will be far less formal, especially if you are just catching up!

If you have ever given a presentation in front of a class, you have given a formal presentation. In such assignments, you were likely being graded, which means there was more at stake for you. Similarly, if you are the leader of an on-campus club, you might occasionally have to speak in front of your club to discuss future plans and events. While this may be less stressful because you are not being graded, you are still operating in a professional capacity, which makes the presentation more formal.

These are just some of the ways you have already given oral reports in your life. Can you think of any other examples and whether they are informal or formal?

Written Reports

Like oral reports, written reports can take many forms that fall somewhere on the spectrum of informal and formal.

As we have discussed, text messages are generally very brief and are best kept short. As a result, they are an informal type of written report. If someone has asked you to text them when you leave, then they are asking for a written report. Emails can also fall into this informal category as well when they are being written to friends and family. However, emails become more formal when written to either a potential employer or co-worker. As you saw in the Job Package section of this textbook, formal writing is essential if you want to convince a potential employer to hire you.

Memos and letters tend to be more formal since they are used in official capacities. However, even those will only be seen by a small audience.

Formal reports are much more technical, and will likely be seen by a larger audience. Therefore, they are much more formal.

Reports and Rhetoric

Hopefully, you have a sense of how you are already creating reports in your daily life. Now, let’s review some examples of reports you may be familiar with (and some you may not be) and discuss how that writing is rhetorical in nature. While all these examples are focused on written reports, you will see examples of a rhetorical oral report later on in this text.

Form Reports

A form report is what it sounds like: a form that you fill out to report something. These reports tend to be very dry and require only concise statements describing the facts. However, each still has a persuasive element.

- Taxes

- If you have ever filed a tax return, you have submitted a form report to the government. This type of form report includes all of your sources of income and your eligible deductions. While most of this information is factual, you are still trying to persuade the government to accept your tax return because you do not want to provoke an audit. Ultimately, you are trying to convince the government that your information is credible.

- Incident Report

- If you have ever worked at a job where safety was a large component, such as a lifeguard, you probably filled out incident reports. In these reports, you were not just describing the incident as you experienced it; rather, you were trying to present it in such a way that the reader will accept your account as true, complete, and unbiased.

- Expense Report

- If you spent your own money for company business, and you wanted to get it back, then you needed to write an expense report that demonstrated your professionalism. Otherwise, the company would not reimburse you.

Even though all of the above examples may appear simple, all of them have a rhetorical element that must be considered when filling them out.

Other Reports

Of course, all reports aren’t as dry and concise as tax forms. After all, only the most basic level of persuasion is required in order to inspire the Canadian Revenue Agency to accept how much money you owe them or for them to pay you money you that you are owed. Sometimes, however, a certain report will require you to focus more carefully on your persuasive skills in order to convince someone to do something with the facts.

- Job Application

- Whenever you compose a job package to apply for a job, you are creating a report. This report describes the education, experiences, and skills that you can offer to a potential employer in the hope of persuading them that your report is true and that your assessment of how you will be a good fit is valid.

- Application to Graduate School

- Similarly, when applying to graduate school, you are trying to persuade the admissions board that you would be a good fit for their program and their school.

- Funding for Business Plan

- If you plan to start your own business, you will write up a business plan. This is a report that you create in order to attain funding for your business. A bank will not give you a loan without a complete report or if they don’t believe you are credible!

In summary, reports take many forms. You have already tried some, and others you have not. Regardless, it’s okay if you are not an expert in any of them. This skill will come with time and plenty of practice. Our goal in this course is to give you the general skills you need to create effective, persuasive reports so that you can apply your knowledge to other situations.

Ultimately, in order to write a really effective report or give a stellar presentation, you will want to apply the rhetorical tools we have already discussed in this course.

How are Reports Rhetorical?

Reports (both written and oral) fall under two categories: informative reports and persuasive reports. Both try to achieve similar, though different, results. With an informative report, you want to establish your credibility so the audience accepts the facts. With persuasive reports, you want to audience to accept the facts, but you may also want to change their thinking and, therefore, their actions.

For this course, you will be creating two reports: a written formal research report and an oral persuasive presentation.

Since both of your reports will be rhetorical in nature, your ultimate goal is to persuade the audience to take action on a topic. The question is, then, how do you accomplish this in your reports? The best place is start with the rhetorical theory that we learned from Bitzer and Aristotle. By using rhetorical theory to assess the situation and to plan a report, your message will become more persuasive.

Over the next couple of chapters, we will walk you through how to apply that theory as you construct your own reports. To help you see how this theory is applied in practice, you will see two students Mei (she/her) and Hamid (he/him) go through their own processes. Mei is working on the written report for this course, and Hamid is working on the persuasive oral presentation. Before they can jump into using the theory, though, they’ll need to come up with a focused topic for their report.

Key Takeaways

- Reports can take many forms. Whether written or oral, you already have experience creating a number different types of reports that range from informal to formal.

- This experience will be a big help to you in this course. What will probably be different for most of you, though, is that you will need to use the rhetorical theory we have discussed in this course to create your messages.

- Specifically, you will be using the theory of Bitzer and Aristotle to craft your reports so that they are persuasive in nature, not simply informative.

References

Leydens, J. (2008). Novice and insider perspectives on academic and workplace writing: Toward a continuum of rhetorical awareness. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 51(3), 242-263. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpc.2008.2001249

an account of your investigation into a subject, presented in a written document or oral presentation that has conventional formatting

the receiver or receivers of a message

the process of a source stimulating a source-selected meaning in the mind of a receiver by means of verbal and non-verbal messages

a type of report where a person is using their voice to relay information

a speech delivery method where a short message is presented without advanced preparation

a quality that allows others to trust and believe you

a report where you establish your credibility so the audience will accept the facts you present

a type of report where a person uses writing to relay information

a report where you want the audience to accept the facts and you want them to change their thinking and actions