Chapter 15: Memos and Letters

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Distinguish between a memo and letter and explain their different purposes in a professional setting.

- Identify the seven elements of the full block letter format.

Key Terms and Concepts

Type your examples here.

- SIDCRA

- Memos

- Header Block

- Letters

- Full block letter format

Professional Correspondence

A lot of your time as a professional will be spent communicating through letters, memos, emails, and text messages. Some of these forms of communication are probably more familiar to you than others; however, as a professional it is important that you understand how and when to use each format and why. This is because your employer will expect you to be able to communicate effectively to maintain your credibility and build relation with co-workers, clients, and the public.

When you craft your correspondence, letters and memos are treated as informal reports and follow the SIDCRA format. Similarly, in a professional context, emails and texts should maintain this organizational structure to help your audience understand and retrieve information quickly. This is why you should begin with the main point for each of these types of correspondence. Busy readers need to be able to scan the document quickly to assess if the document requires immediate attention.

As always, before you begin to write, consider your audience’s needs and your purpose for writing in the first place. For all correspondence, you should:

- Include a detailed subject line which provides a summary, or a sense of purpose for the document,

- Provide a brief introduction which states the purpose for writing and provides an overview or forecasting of the rest of the document,

- Provide necessary context for your reader in either the introduction or in a background paragraph,

- Use headings to help your reader find information quickly, and to help you, the writer, organize information effectively, and

- Keep paragraphs short and focused on one main point.

To decide which format to use, consider the size and importance of your audience, your purpose for writing, and the complexity of the information being communicated.

Although RCM 200 introduces standard templates and formats, there is some room for variation, and you should always follow your employer’s particular preference for letter, memo, and email format.

For this chapter, we will focus on memos and letters. The following chapter will be on email and text messages.

Memos

Memoranda, or memos, are one of the most versatile document forms used in professional settings. Memos are “in house” documents (sent within an organization) to pass along or request information, outline policies, present short reports, or propose ideas. While they are often used to inform, they can also be persuasive documents. A company or institution typically has its own “in house” style or template that is used for documents such as letters and memos.

Memo Format

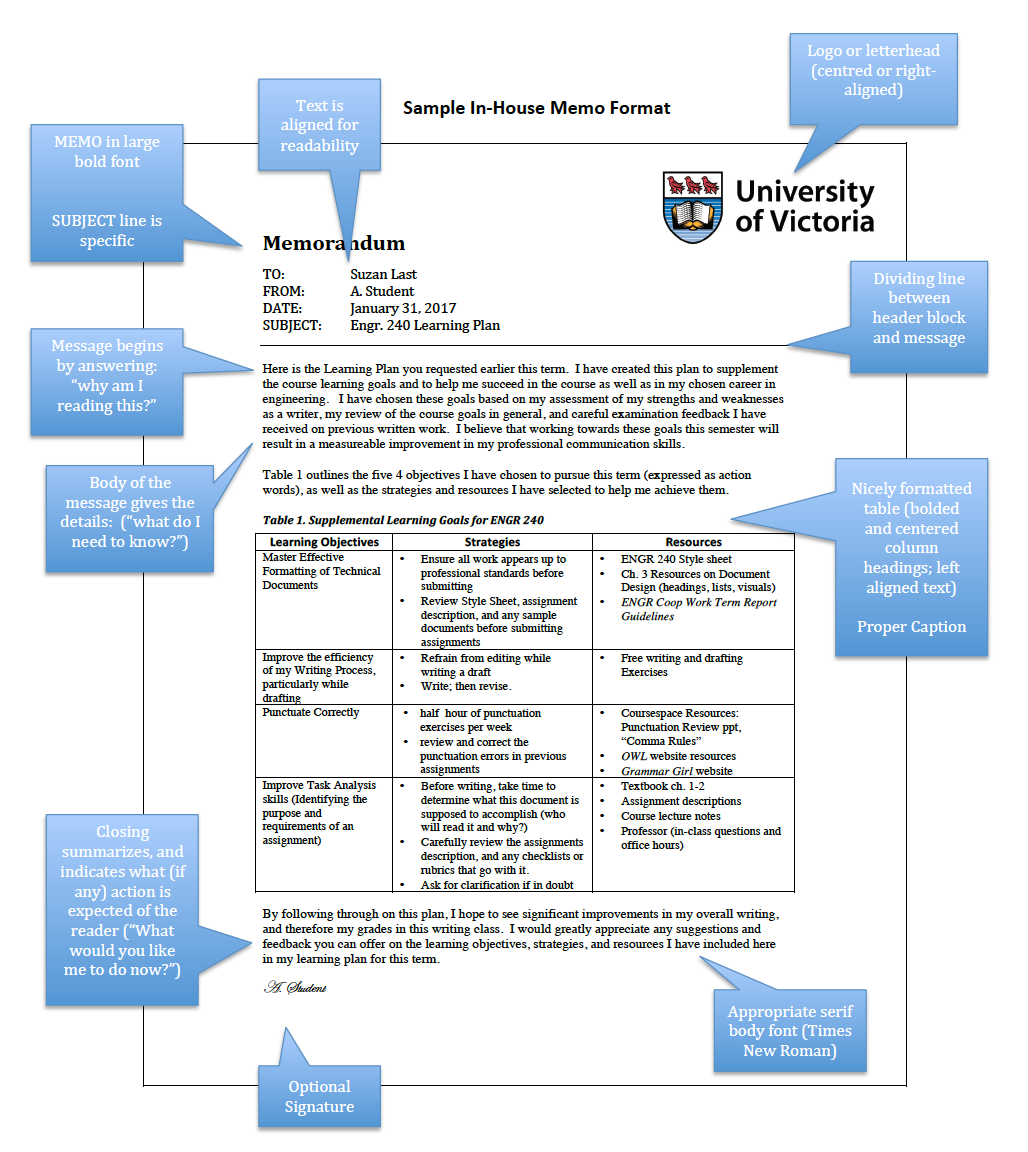

Figure #1 below shows a sample of an “in house” memo style (the style we will use for memo assignments written for this class), with annotations pointing out various relevant features. The main formatted portions of a memo are the Logo or Letterhead (which is optional), the Header Block, and the Message.

The Header Block

The Header Block appears at the top left side of your memo, directly underneath the word MEMO or MEMORANDUM in large, bold, capitalized letters. This section contains detailed information on the recipient, sender, and purpose. It includes the following lines:

- TO: give the recipient’s full name, and position or title within the organization

- FROM: include the sender’s (your) full name and position or title

- DATE: include the full date on which you sent the memo

- SUBJECT or RE: write a brief phrase that concisely describes the main content of your memo.

Place a horizontal line under your header block, and place your message below.

The Message

The length of a memo can range from a few short sentences to a multi-page report that includes figures, tables, and appendices. Whatever the length, there is a straightforward organizational principle you should follow. Organize the content of your memo so that it answers the following questions for the reader:

- Opening: Do I have to read this? Why do I have to read this?

- Details: What do I need to know?

- Closing: What am I expected to do now?

The Opening

Memos are generally very direct and concise. There is no need to start with general introductions before getting to your point. Your readers are colleagues within the same organization and are likely familiar with the context you are writing about. The opening sentences of the memo’s message should make it clear to the reader whether they have to read this entire memo and why. For example, if the memo is informing me about an elevator that’s out of service in a building I never enter, then I don’t really have to read any further?

The Details

The middle section of the message should give all of the information needed to adequately inform the readers and fulfill the purpose of the memo. Start with the most general information, and then add the more specific facts and details. Make sure there is enough detail to support your purpose, but don’t overwhelm your readers with unnecessary details or information that is already well known to them.

The Closing

The final part of the message indicates what, if any, action is required or requested of the readers. If you are asking your readers to do something, be as courteous as possible, and try to indicate how this action will also benefit them.

For more information on writing memos, check out the memo page on the the Online Writing Lab at Purdue University: Parts of a Memo.

Exercise #1: Sample Memo

Below are two images. The first shows a potential memo layout with tips for creating one. The second shows a sample memo.

Does the sample memo have all the parts we’ve discussed in this section? Does it need more information? Less? Is there anything you think would be helpful for the author to include?

Letter

Letters are brief messages sent to recipients that are often outside the organization, or external. They are often printed on letterhead paper that represents the business or organization, and are generally limited to one or two pages. While email and text messages may be used more frequently today, the business letter remains a common form of written communication as it serves many functions, such as:

- introducing you to a potential employer

- announcing a product or service

- communicating feelings and emotions (complaint letters, for example).

Letters are the most formal format for business correspondence, and your credibility will be established by using a formal tone and a conventional format for the document.

Use a letter format for communicating with people outside of your own organization, or for information which will be kept on file (such as a letter of offer from an employer) or may be needed for legal proceedings. Your reader will expect a well written and well formatted document. The full block letter format is the most straightforward letter format and will be covered in the next section. Professionals who produce their own correspondence using this format will appreciate its simplicity and consistency.

As we will soon see, there are many types of letters, and many adaptations in terms of form and content.

The Full Block Letter Format

A typical letter has 7 main elements, which make up the full block letter format.

- Letterhead/logo: Sender’s name and return address

- The heading: names the recipient, often including address and date

- Salutation: “Dear ______ ” use the recipient’s name, if known.

- The introduction: establishes the overall purpose of the letter

- The body: articulates the details of the message

- The conclusion: restates the main point and may include a call to action

- The signature line: sometimes includes the contact information

You can see how these elements are implemented in the example above. Keep in mind that letters represent you/or and your company in your absence. In order to communicate effectively and project a positive image, remember that

- your language should be clear, concise, specific, and respectful

- each word should contribute to your purpose

- each paragraph should focus on one idea

- the parts of the letter should form a complete message

- the letter should be free of errors.

Exercise 2: Sample letter

Types of Messages

Letters and memos can be written for many purposes. Here are just a few reasons you may have to write these documents in your professional career. We will also provide some tips for each one.

Making a Request

Whenever you make a request, whether in a memo or letter, remember to consider the tone of your words: be polite and be respectful. It is certainly easier, and faster, to send off a message without proofreading it, but doing so will help you make sure that you do not sound demanding or condescending to your audience.

Remember that your request will add to your audience’s already busy day, so acknowledge the time and effort necessary to address your request. Finally, always be as specific as possible about what you expect your reader to do and provide the necessary information so that the reader can successfully fulfill your request.

When making a request you should:

- quickly establish relation, and then begin with the main point

- explain in the body of the document your needs and provide details to justify the request

- end by extending goodwill and appreciation

- always be courteous and proofread to eliminate poor tone

Thank-Yous

Thank-you letters may feel like an old-fashioned way to communicate, but even in today’s fast-paced world, a well-written thank you letter can establish your credibility and professionalism. A hand written thank-you letter is always most appropriate, but a business thank-you letter may be printed on company stationery.

A thank-you letter does not need to be long, but it should communicate your sincere appreciation to the reader.

- Be specific about what you are thanking the reader for. Avoid clichés and stock phrases.

- Include some details about why you are thankful and how you benefited from the reader’s actions.

- End with a sincere compliment and repeat the thank-you.

Interview Thank-You Note

A brief thank-you letter or thank-you email is an important step in the interview and job search process. Not only will the note of thanks communicate your professionalism, but it will also give you an opportunity to demonstrate your commitment to the company. Use this opportunity to remind the reader why you are the best candidate for the position.

“Good News” Messages

Obviously, preparing a good news message (such as a message of of Congratulations, Acknowledgement, and Acceptance) is easier than preparing a negative message. However, care should be taken in all correspondence to maintain your credibility as a professional.

- Be specific about the achievement or award.

- Be sincere in your congratulations.

- Avoid using language which might sound patronizing or insincere.

“Bad News” Messages

In the course of your professional career, you are going to need to write negative messages (such as messages of Complaint or Refusal) for a variety of reasons. Tone is very important here; comments should be made using neutral language and should be as specific as possible.

A thoughtful writer will remember that the message will likely have negative consequences for the audience, and although it may be appropriate to begin with a buffer sentence to establish relation, get to the main point as quickly as possible. Keep your audience’s needs in mind; your audience will need to clearly understand your decision and your reasons for making such a decision.

Do not hide your bad news in ambiguous language to save your own sense of face. Finally, remember to be courteous and considerate of your audience’s feelings. Avoid inflaming the situation with emotional, accusatory, or sarcastic language, and avoid personal attacks on your reader.

- Be polite and use neutral language.

- Be specific about the bad news you are conveying.

- Provide relevant details so your audience can understand your decision.

- End with an appropriate closing; avoid insincere or falsely positive endings which are disrespectful to your audience.

Apology / Conciliation

Learning how to apologize well is an important skill for young professionals. A poorly written apology can exacerbate problems for both you and your company. Don’t apologize unnecessarily, but when an apology is in order, do so sincerely and with full recognition of your audience’s hurt, frustration and disappointment.

Once you reach a leadership position in your field, you may also need to apologize for someone else’s error. As a leader in an organization, it will be your job to take responsibility and to apologize fully to maintain your organization’s credibility.

Sincere apologies focus on the audience’s needs and feelings, not the needs and feelings of the person issuing the apology. Avoid the ubiquitous “this is not who I am” phrase as part of an apology because saying “this is not who I am” is not an apology at all. If you do something that requires an apology, take responsibility and recognize that your actions or words caused hurt or inconvenience for someone else. An apology must also be sincere; an accusation veiled as as an apology will not persuade anyone that you are actually sorry. A phrase such as “I am sorry you feel that way” will not convince your audience that you are sincerely sorry. An apology should:

- Sincerely acknowledge that you are sorry for the words or actions which caused harm

- Acknowledge that the audience’s hurt, frustration, or anger is real, and warranted

- Take responsibility for the mistake and the negative consequences of the mistake

- Never suggest that the audience is somehow to blame for the problem

- Offer some form of compensation if it seems appropriate to do so

Transmittal Letters

When you send a report or some other document (such as a resumé) to an external audience, send it with a letter that briefly explains the purpose of the enclosed document and a brief summary. For more information on these kinds of transmittal documents for reports, visit Chapter 29: Formatting the Report. For more information on cover letters, visit Chapter 19: Cover/Application Letters.

Click the link to download a Letter of Transmittal Template (.docx).

Letters of Inquiry

You may want to request information about a company or organization such as whether they anticipate job openings in the near future or whether they fund grant proposals from non-profit groups.

In this case, you would send a letter of inquiry, asking for additional information. As with most business letters, keep your request brief, introducing yourself in the opening paragraph and then clearly stating your purpose and/or request in the second paragraph. If you need very specific information, consider placing your requests in list form for clarity. Conclude in a friendly way that shows appreciation for the help you will receive.

Follow-up Letters

Any time you have made a request of someone, write a follow-up letter expressing your appreciation for the time your letter-recipient has taken to respond to your needs or consider your job application. If you have had a job interview, the follow-up letter thanking the interviewer for his/her time is especially important for demonstrating your professionalism and attention to detail.

Exercise #3: Letters

Letters within the professional context may take on many other purposes, such as communicating with suppliers, contractors, partner organizations, clients, government agencies, and so on.

Below are three images of letters. The first shows a layout using the full-block format discussed above. The second image is a cover letter, the second is a transmittal letter.

Do the sample letters have all the parts we’ve discussed in this section? If so, what do they still need? Is there anything you think would be helpful for the author to include?

For additional examples of professional letters, take a look at the sample letters provided by David McMurrey in his online textbook on technical writing: Online Technical Writing: Examples, Cases & Models.

Key Takeaways

- Even in the digital age, writing correspondence will be a regular part of your professional career. Not only do these types of correspondence help maintain your credibility as an employee, they help you build relation with co-workers, clients, and the public.

- Memos are in house, internal documents that serve a number of purposes, such as passing along information or proposing ideas. Their format includes a Header Block followed by the message itself. A message has three parts: the opening, details, and a closing.

- Letters are more formal than memos, since they are generally externally sent to people outside of a company or organization. They use a full block format which is the standard for most organizations. Like memos, there are many different reasons you may write a letter.

Attributions

This chapter is adapted from “Technical Writing Essentials” by Suzan Last (on BCcampus). It is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

a quality that allows others to trust and believe you

an acronym that stands for the six parts of a report: (1) summary, (2) introduction, (3) discussion, (4) conclusion, (5) recommendations, (6) appendix

full name "memoranda," these are documents sent within an organization to pass along or request information, outline policies, present short reports, or propose ideas

a brief message to recipients that are often outside the organization

the attitude of a communicator toward the message being delivered and/or the audience receiving the message

our sense of self-worth in a given situation

the section of a memo that contains detailed information on its recipient, sender, and purpose

brief messages sent to recipients that are often outside an organization

a standard letter format that has seven elements: (1) letterhead/logo, (2) the heading, (3) salutation, (4) the introduction, (5) the body, (6) the conclusion, (7) the signature line