Chapter 27: Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Summarizing Sources

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Integrate sources into your writing by using a lead-in, a source, and analysis

- Differentiate between direct quotes, paraphrase, and summary and explain when to use each integration method

- Edit direct quotes on the grammatical level by using the seamless integration method, signal phrase method, and colon method

- Apply the five-step process for paraphrasing to different texts to write your own paraphrases

- Apply the three-step process for summarizing to a piece of media that you enjoy

Key Terms and Concepts

- plagiarism

- direct quote

- paraphrase

- summary

We are now officially in the second stage of the report writing process: producing your report!

By now, you should be off to a good start with your formal research report. You have used rhetorical theory to plan out your message and you already have several sources that you want to use. The question we must now address is how you include those sources into your writing in a professional way?

Academic integrity plays a huge role here. You obviously don’t want to copy a source’s research word for word and claim it as your own. That would be plagiarism. However, you also don’t want to only copy large chunks of the text and just put that in your paper either. That would be poor writing. Instead, you want to include a combination of both where you use the work of others to help support your arguments and ideas. This chapter will walk you through how to do this.

Integrating Materials Into Your Report

Exercise #1: Interactive Video

Let’s begin with a video that provides an overview of the source integration process. Some of these practices are probably already be familiar to you.

One of the most important takeaways from the video is that it is not enough to simply present information from your sources in your paper. You must also draw your own conclusions. Otherwise you are simply restating someone else’s work, and you are not furthering your argument. Many students forget this crucial step in writing reports. Thankfully, it’s a relatively easy fix once you know what to do. We will first walk you through the structure you need to follow, and then show you how to use it to incorporate direct quotes, paraphrase, and summary in your report.

The Source Integration Structure

Read the example paragraph below. What is wrong with it?

A couple of things should stand out. The most obvious is that the paragraph is almost exclusively direct quotes. We have a little bit of the student’s input at the start and end of the paragraph, but there isn’t really anything substantial in-between the quotes.

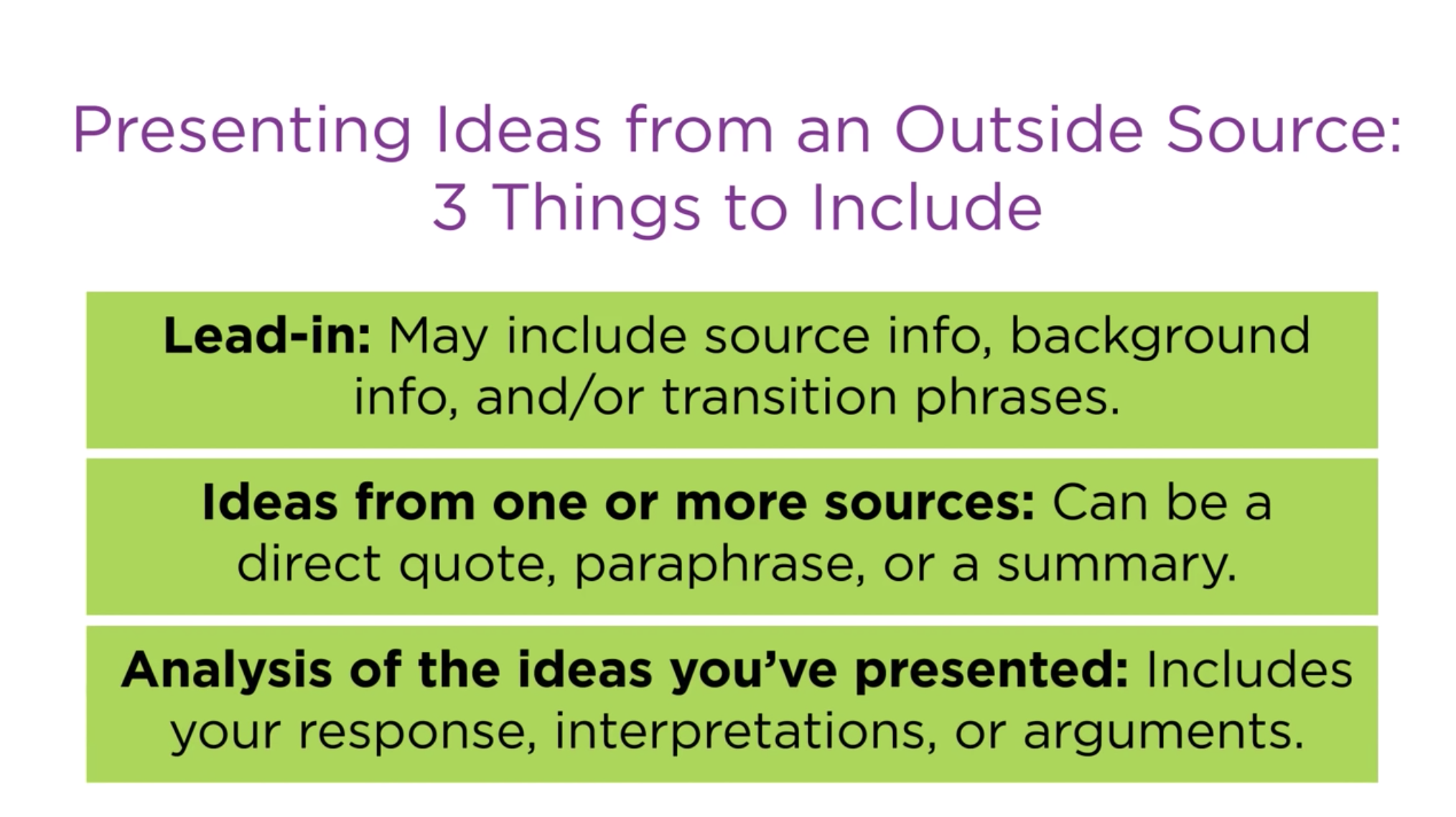

Ultimately, the student didn’t incorporate all three elements for integrating sources that are recommended in the above video. As a reminder they are:

Let’s look at the same paragraph again, but highlight the three elements we have discussed. This will show you visually how the paragraph is arranged. We will use the following colors:

Lead-in

Idea from a Source

Analysis

We do have some lead-in for the quotes, but almost no analysis is given. Yes, the quoted information may be relevant, but it is not immediately clear how it’s relevant to the writer’s main point because there is not enough analysis.

Students often mistakenly assume that their readers will figure out the relevance on their own, but that is not the case. It is not the reader’s job to interpret your writing for you. It is up to you to be as explicit as possible by connecting your sources to your argument.

Let’s look at a revised version of the above paragraph that does a better job incorporating a lead-in, a source, and analysis. We have color coded the three elements again so you can better see where they are in the paragraph:

Direct Quotes, Paraphrasing, and Summary

When writing in academic and professional contexts, you are required to engage with the words and ideas of other authors. Therefore, being able to correctly and fluently incorporate other writers’ words and ideas in your own writing is a critical writing skill. As you now know, there are three main ways to integrate evidence from sources into your writing:

One important note that we haven’t mentioned is that you are required to include a citation anytime you are using another person’s words and/or ideas. This means that even if you do not quote directly, but paraphrase or summarize source content and express it in your own words, you still must give credit to the original authors for their ideas. Your RCM 200 instructor will be making sure you do this when they read your formal written report.

You have already seen the use of citations in action throughout this textbook. Anytime we have integrated content from another source, you will have seen a citation that looks something like this:

(Smith, 2020)

These citations are done using the American Psychology Association (APA) style. You will be expected to use this citation style in your own paper. However, if you are not sure how to do APA citation correctly, don’t worry. We will go into the specific mechanics of how to cite sources in the next chapter.

We will now walk you through each source integration method, giving you opportunities to practice each one. If at any point you’re confused, or unclear, don’t hesitate to ask your instructor for help. The University of Saskatchewan Writing Centre is also a great resource.

Direct Quotes

A direct quote is the word-for-word copy of someone else’s words and/or ideas. This is noted by quotation marks (” “) around those words. Using quotations to support your argument has several benefits over paraphrase and summary:

- Integrating quotations provide direct evidence from reliable sources to support your argument

- Using the words of credible sources conveys your credibility by showing you have done research into the area you are writing about and consulted relevant and authoritative sources

- Selecting effective quotations illustrates that you can extract the important aspects of the information and use them effectively in your own argument

However, be careful not to over-quote. As we saw in the above example, if you over-quote, you risk relying too much on the words of others and not your own.

Quotations should be used sparingly because too many quotations can interfere with the flow of ideas and make it seem like you don’t have ideas of your own.

When should you use quotations?

- If the language of the original source uses the best possible phrasing or imagery, and no paraphrase or summary could be as effective; or

- If the use of language in the quotation is itself the focus of your analysis (e.g., if you are analyzing the author’s use of a particular image, metaphor, or other rhetorical strategy).

How to Integrate Quotations Correctly

Integrating quotations into your writing happens on two levels: the argumentative level and the grammatical level.

The Argumentative Level

At the argumentative level, the quotation is being used to illustrate or support a point that you have made, and you will follow it with some analysis, explanation, comment, or interpretation that ties that quote to your argument.

As we mentioned earlier, this is where many students run into trouble. This is known as a “quote and run.” Never quote and run. This leaves your reader to determine the relevance of the quotation, and they might interpret it differently than you intended! A quotation, statistic or bit of data cannot speak for itself; you must provide context and an explanation for the quotations you use. As long as you use the three steps we listed above for integrating sources, you will be on the right track.

The Grammatical Level

The second level of integration is grammatical. This involves integrating the quotation into your own sentences so that it flows smoothly and fits logically and syntactically. There are three main methods to integrate quotations grammatically:

- Seamless Integration Method: embed the quoted words as if they were an organic part of your sentence. This means that if you read the sentence aloud, your listeners would not know there was a quotation.

- Signal Phrase Method: use a signal phrase (Author + Verb) to introduce the quotation, clearly indicating that the quotation comes from a specific source

- Colon Method: introduce the quotation with a complete sentence ending in a colon.

Let’s see this in action. Consider the following opening sentence (and famous comma splice) from A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens, as an example:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

Dickens, C. (2017). A tale of two cities. Alma Books Ltd. p. 5

Below are examples of the quote being integrated using the three methods.

1. Seamless Integration: embed the quotation, or excerpts from the quotation, as a seamless part of your sentence

Charles Dickens (2017) begins his novel with the paradoxical observation that the eighteenth century was both “the best of times” and “the worst of times” (p. 5).

2. Signal Phrase: introduce the author and then the quote using a signal verb (scroll down to see a list of common verbs that signal you are about to quote someone)

Describing the eighteenth century, Charles Dickens (2017) observes, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” (p. 5).

3. Colon: if your own introductory words form a complete sentence, you can use a colon to introduce and set off the quotation. This can give the quotation added emphasis.

Dickens (2017) defines the eighteenth century as a time of paradox: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” (p. 5).

The eighteenth century was a time of paradox: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” (Dickens, 2017, p. 5).

It’s important that you not rely on any one grammatical method in your own writing. Instead, try to use a balance of methods to make your writing seem more dynamic and varied.

Editing Quotations

When you use quotation marks around material, this indicates that you have used the exact words of the original author. However, sometimes the text you want to quote will not fit grammatically or clearly into your sentence without making some changes. Perhaps you need to replace a pronoun in the quote with the actual noun to make the context clear, or perhaps the verb tense does not fit. There are two main ways to edit a quotation to make it fit grammatically with your own sentence:

- Use square brackets: to reflect changes or additions to a quote, place square brackets around any words that have been changed or added.

- Use ellipses: ellipses show that some text has been removed. They can have either three dots (. . .) or four dots (. . . .). Three dots indicate that some words have been removed from the sentence; four dots indicate that a substantial amount of text has been deleted, including the period at the end of a sentence.

Let’s look at this in action using the quote below.

“Engineers are always striving for success, but failure is seldom far from their minds. In the case of Canadian engineers, this focus on potentially catastrophic flaws in a design is rooted in a failure that occurred over a century ago. In 1907 a bridge of enormous proportions collapsed while still under construction in Quebec. Planners expected that when completed, the 1,800-foot main span of the cantilever bridge would set a world record for long-span bridges of all types, many of which had come to be realized at a great price. According to one superstition, a bridge would claim one life for every million dollars spent on it. In fact, by the time the Quebec Bridge would finally be completed, in 1917, almost ninety construction workers would have been killed in the course of building the $25 million structure”

Petroski, H. (2012). The obligation of an engineer. In To forgive design: Understanding failure (pp. 175-198). Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674065437

You are allowed to change the original words, to shorten the quoted material or integrate material grammatically, but only if you signal those changes appropriately with square brackets or ellipses:

Example 1: Petroski (2012) observed that “[e]ngineers are always striving for success, but failure is seldom far from their minds” (p. 175).

Example 2: Petroski (2012) recounts the story of a large bridge that was constructed at the beginning of the twentieth century in Quebec, saying that “by the time [it was done], in 1917, almost ninety construction workers [were] killed in the course of building the $25 million structure” (p. 175)

Example 3: “Planners expected that when completed the … bridge would set a world record for long-span bridges of all types” (Petroski, 2012, p. 175).

In summary, there are a lot of ways you can approach integrating quotes. You can even change certain elements of your quote as long you indicate this with proper punctuation.

Exercise #2: Integrating a Quote at the Grammatical Level

Below is an excerpt from William Zinsser’s “Simplicity.” After you read the excerpt, write your own sentences using all three integration methods we have discussed. Don’t forget, you can change the quotes slightly if you need to. Just ensure that you are using ellipses or square brackets to indicate this. Also, try to say something interesting about the words you are quoting. Don’t just say “Zinsser (1980) says ‘insert quote.'” Your sentence(s) should express your own ideas.

You’ll notice that there is no page number associated with this quote. That is because this version comes from a website, which does not have page numbers.

Once you are done, compare them to the examples below. If your approach is different that’s totally fine. If you’re not sure that you did it correctly, please check with your instructor.

Zinsser, W. K. (1980). Simplicity. In On writing well: An informal guide to writing nonfiction. Harper Perennial.

Paraphrase and Summary

Unlike direct quotes, which use a source’s exact wording, paraphrase and summary allow you to use your own words to present information. While the approach to using both methods is similar, the reason you will choose one over the other is different.

A paraphrase is typically more detailed and specific than a summary. It also retains the length of the original source.

A summary, on the other hand, is used when describing an entire source. For example, if you want to emphasize the main ideas of a source, but not go into a great detail, then a summary is usually best.

Paraphrase

Exercise #3: Interactive Video

Watch the interactive video below on paraphrasing. It will explain when paraphrasing is preferable over direct quotes, how to correctly paraphrase a source, and how to combine a paraphrase and direct quote in the same sentence.

The video will stop at different points to test your knowledge. Make sure you answer the questions. Additionally, take note of the 5 steps for paraphrasing as you watch.

Link to Original Video: tinyurl.com/paraprocess

As the video states, paraphrasing is when you put source text in your own words and alter the sentence structure to avoid using direct quotes. Paraphrasing is the preferred way of using a source when the original wording isn’t important. This way, you can incorporate the source’s ideas so they’re stylistically consistent with the rest of your document and thus better tailored to the needs of your audience. Also, paraphrasing a source into your own words proves your advanced understanding of the source text. The video lists five steps for paraphrasing a source. They are:

- Read the source material until you fully understand the author’s meaning. This may take 3-4 readings to accomplish.

- Take notes and list key terms that you can use in your paraphrase

- Write your own paraphrase without looking at the source material. You should include the key terms that you wrote down

- Check that your version captures the intent of the original and all important information

- Provide in-text (parenthetical) citation

We will go through this in a bit more detail below. However, if you feel like you understand, feel free to skip down to the next part.

An In-Depth Look at Paraphrase

A paraphrase must faithfully represent the source text by containing the same ideas as the original in about the same length. Let’s walk through the five steps mentioned in the video above to create a paraphrase for the following text:

Students frequently overuse direct quotation [when] taking notes, and as a result they overuse quotations in the final [research] paper. Probably only about 10% of your final manuscript should appear as directly quoted matter. Therefore, you should strive to limit the amount of exact transcribing of source materials while taking notes.

Lester, J. D. (1976). Writing research papers: A complete guide. Pearson Scott Foresman.

Step 1: Read the Source Material Until You Fully Understand It

What are these three sentences about? What information do they give us?

They discuss how students rely too much on direct quotations in their writing. It also explains just how much of a final paper should include direct quotes. Seems clear enough, so lets move on to the next step.

Step 2: Take Notes and List Key Terms for Your Paraphrase

The key terms you come up with for your paraphrase will depend on what information you want to convey to the reader. For our purposes, let’s say you want to use Lester (1976) to highlight how much students over-quote in their papers. You may focus on the following key terms:

- 10%

- students

- research.

Notice that this is only 3 words from the original text, which has over 50 words! This may not seem like much, but it’s definitely enough words for our paraphrase.

Step 3: Using Key Terms, Write Your Own Paraphrase Without Looking at Original

Let’s try to put together a paraphrase. As a matter of good writing, you should try to streamline your paraphrase so that it tallies fewer words than the source passage while still preserving the original meaning. An accurate paraphrase of the original passage above, for instance, can reduce the three-line passage to two lines without losing or distorting any of the original points. Here’s our attempt with the key terms highlighted in yellow:

Lester (1976) advises against exceeding 10% quotation in your written work. Since students writing research reports often quote excessively because of copy-cut-and-paste note-taking, they should try to minimize using sources word for word (Lester, 1976).

This isn’t necessarily a perfect example of a paraphrase, but it is certainly a good start! Time to move on to the next step.

Step 4: Compare Your Paraphrase to the Original

Here is the original text with our paraphrase:

Original: Students frequently overuse direct quotation [when] taking notes, and as a result they overuse quotations in the final [research] paper. Probably only about 10% of your final manuscript should appear as directly quoted matter. Therefore, you should strive to limit the amount of exact transcribing of source materials while taking notes.

Paraphrase: Lester (1976) advises against exceeding 10% quotation in your written work. Since students writing research reports often quote excessively because of copy-cut-and-paste note-taking, they should try to minimize using sources word for word (Lester, 1976).

Notice that, even though we only have three key terms, we didn’t have to repeat any two-word sequences from the original. This is because we have changed the sentence structure in addition to most of the words. This can definitely take a couple of tries, so if you don’t get it right away, that’s okay. If you’re still stuck, check in with your instructor or the University of Saskatchewan Writing Centre.

Step 5: Provide an In-Text Citation

We’ve already done this step twice in our paper: once at the start of our paper with “Lester (1976) advises…” and once at the end with “(Lester, 1976).” We’ll talk about how to do this more in-depth in the next chapter.

Common Plagiarism Issues with Paraphrase

As we mentioned in the previous section, when paraphrasing, it is important to change both the words and sentence structure of the original text. However, many students struggle with the first part. They will typically only substitute major words (nouns, verbs, and adjectives) here and there while leaving the source passage’s basic sentence structure intact. This inevitably leaves strings of words from the original untouched in the “paraphrased” version, which can be dangerous because including such direct quotation without quotation marks will be caught by the plagiarism–busting software that college instructors use these days.

Consider, for instance, the following poor attempt at a paraphrase of the Lester (1976) passage that substitutes words selectively. Like last time, we have included the original text with the incorrect paraphrase. We have also highlighted the unchanged words in yellow.

Original Quote: Students frequently overuse direct quotation [when] taking notes, and as a result they overuse quotations in the final [research] paper. Probably only about 10% of your final manuscript should appear as directly quoted matter. Therefore, you should strive to limit the amount of exact transcribing of source materials while taking notes (Lester, 1976).

Poor Paraphrase: Students often overuse quotations when taking notes, and thus overuse them in research reports (Lester, 1976). About 10% of your final paper should be direct quotation. You should thus attempt to reduce the exact copying of source materials while note taking (Lester, 1976).

As you can see, several strings of words from the original are left untouched because the writer didn’t change the sentence structure of the original. Plagiarism-catching software, like Turnitin, specifically look for this kind of writing and produce Originality Reports to indicate how much of a paper is plagiarized. In this case, the Originality Report would indicate that the passage is 64% plagiarized because it retains 25 of the original words (out of 39 in this “paraphrase”) but without quotation marks around them.

Correcting this by simply adding quotation marks around passages such as “when taking notes, and” would be unacceptable because those words aren’t important enough on their own to warrant direct quotation. The fix would just be to paraphrase more thoroughly by altering the words and the sentence structure, as shown in the paraphrase a few paragraphs above.

Exercise #4: Paraphrase Practice

Now try it on your own. Below are three pieces of original text from the McCroskey, MacLennan, and Booth readings from this course. Try writing your own paraphrases for each one and compare them to the examples below. Note that the key words in the examples are highlighted. If your version is different that’s okay as long as you follow the steps we listed out. If you’re not sure if you’re paraphrase is correct, check with your instructor.

(1) “Rhetorical communication is goal-directed. It seeks to produce specific meaning in the mind of another individual. In this type of communication there is specific intent on the part of the source to stimulate meaning in the mind of the receiver” (McCroskey, 2015, p. 22).

(2) “The successful professional must therefore be able to present specialized information in a manner that will enable non-specialist readers to make policy, procedural, and funding decisions. In order to do this, a technical specialist’s communication, like that of any other professional, must establish and maintain credibility and authority with those who may be unfamiliar with technical subjects (MacLennan, 2009, p. 4)

(3) The common ingredient that I find in all of the writing I admire—excluding for now novels, plays and poems—is something that I shall reluctantly call the rhetorical stance, a stance which depends on discovering and maintaining in any writing situation a proper balance among the three elements that are at work in any communicative effort: the available arguments about the subject itself, the interests and peculiarities of the audience, and the voice, the implied character, of the speaker. I should like to suggest that it is this balance, this rhetorical stance, difficult as it is to describe, that is our main goal as teachers of rhetoric (Booth, 1963, p. 141).

Summary

Summarizing is one of the most important skills in professional communication. Professionals of every field must explain to non-expert customers, managers, and even co-workers the complex concepts on which they are experts, but in a way that those non-experts can understand. Adapting the message to such audiences requires brevity but also translating jargon-heavy technical details into plain, accessible language.

Fortunately, the process for summarizing is very similar to paraphrasing. Like paraphrasing, a summary is putting the original source in your own words. The main difference is that a summary is a fraction of the source length—anywhere from less than 1% to a quarter depending on the source length and length of the summary.

A summary can reduce a whole novel or film to a single-sentence blurb, for instance, or it could reduce a 50-word paragraph to a 15-word sentence. It can be as casual as a spoken overview of a meeting your colleague was absent from, or an elevator pitch selling a project idea to a manager. It can also be as formal as a memo report to your colleagues on a conference you attended on behalf of your organization.

When summarizing, you will follow the same process as a paraphrase, but with a few additional steps:

-

- Determine how big your summary should be (according to your audience’s needs) so that you have a sense of how much material you should collect from the source.

- Pull out the main points, which can usually be found in places like the summary portion of a report, the introduction, the abstract at the beginning of an article, or a topic sentence at the beginning of a paragraph.

- Disregard detail such as supporting evidence and examples. These elements belong in a paraphrase, not a summary.

- How many points you collect depends on how big your summary should be (according to audience needs).

- Don’t forget to cite your summary.

Exercise #5: Summary Practice

You have already had a lot of practice summarizing in your daily life. Any time you tell someone about a book, movie, or TV show you like, you are summarizing. You are obviously not going to spend time going over every chapter, every scene, or every episode in excruciating detail. Instead, you will just talk about the main points, the number of which will depend how long your summary needs to be.

Here are some examples. Below are summaries for two very different sources: the Harry Potter franchise and the Nine Axioms reading you did a few weeks ago. There are three summaries for each source: one that is 45 words long, one that is 30 words long, and one that is 15 words long. What information is cut to make the summaries more succinct? Are there any important details lost between the different summaries?

What’s Harry Potter about?

45 word summary: It’s about a British boy named Harry Potter who finds out he is a wizard. He goes to a magic school called Hogwarts where he becomes friends with Ron and Hermione. Together, they learn how to cast spells and fight an evil wizard named Voldemort (Rowling, 2015).

30 word summary: It’s about a boy named Harry Potter who finds out he is a wizard. He goes to a school called Hogwarts where he learns magic and fights an evil wizard (Rowling, 2015).

15 word summary: It’s about a boy named Harry who attends a magic school and fights evil wizards (Rowling, 2015).

What are MacLennan’s Nine Axioms?

45 word summary: The Nine Axioms of Communication are nine interconnected principles that can help us design effective messages. They explain why communication works and, just as importantly, why it doesn’t. More specifically, they are tools that will help us identify effective communication strategies and diagnose communication problems (MacLennan, 2009).

30 word summary: They are nine interconnected principles of communication that MacLennan (2009) wrote to help us understand how communication works. They also help us identify effective communication strategies and diagnose any communication problems.

15 word summary: They’re nine principles that show how communication works, identify effective communication strategies, and diagnose problems (MacLennan, 2009).

Again, notice that neither summary goes into great detail about the topic. They just stress the main points. The Harry Potter summary doesn’t go into all the adventures that happen in the books, and the Nine Axioms summary doesn’t list out all Nine Axioms. Knowing what information to keep is essential in writing a good summary.

Now it’s your turn. Pick a movie, TV show, or book that you really like. Write three summaries about the thing you selected: one that is 45 words long, one that is 30 words long and one that is 15 words long. You don’t need to include a citation. For an extra challenge, try to make your summaries the exact number of words.

Once you are done, compare your three summaries. What is different between them? How did the different length requirements affect your writing? What elements did you have to cut? Why were those elements not as important?

Key Takeaways

- Avoiding plagiarism should always be a concern when you are doing research for a report. Even in the professional world, it’s important to make sure you are integrating your sources in an ethical way. Not doing so can result in fines and even termination from your job.

- Many students struggle with this on an organizational level. They tend to think they can just stack quotes on top of quotes and that will be enough, but it is definitely not!

- Instead, you should always use three things when integrating outside sources into your writing: a lead-in, the source, and your analysis. Having a balance of all three will make your writing more persuasive.

- You can include ideas from a source in one of three ways: direct quotes, paraphrase, and summary.

- Direct quotes are best when the language of the original source is the best possible phrasing or imagery and a paraphrase/summary could not be as effective. It is also preferable if you are planning to analyze the specific language in the quotation (such as a metaphor or rhetorical strategy).

- Paraphrasing is best when the original wording of a source is not important. This means that you can incorporate a source’s ideas in such a way that they’re stylistically consistent with the rest of your document. This allows you flexibility to better tailor your writing to the needs of your audience.

- A Summary is best when you want to focus on only the main ideas of a source. The length of your summary will depend on your needs, but it’s not uncommon for a summary to be less than 1% to a quarter the length of the original source.

References

Dickens, C. (2017). A tale of two cities. Alma Books Ltd.

Lester, J. D. (1976). Writing research papers: A complete guide. Pearson Scott Foresman.

Petroski, H. (2012). The obligation of an engineer. In To forgive design: Understanding failure (pp. 175-198). Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674065437

Attributions

This chapter is adapted from Technical Writing Essentials (on BCcampus) by Suzan Last and Candice Neveu. It is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This chapter is also adapted from Business Communications for Fashion (on openpress.usask.ca) by Anna Cappuccitti. It is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

when a person represents the ideas of another as their own original work

a word-for-word copy of someone else's words and/or ideas.

a way to use your own words to present information. This method is more detailed and specific than a summary and retains the length of the original source.

a way to use your own words to present your own information. This method is used for describing an entire source. This means that you will focus only on main ideas and not go into details.

a quality that allows others to trust and believe you

an account of your investigation into a subject, presented in a written document or oral presentation that has conventional formatting