Introduction

The provincial motto in Saskatchewan is From Many Peoples Strength, a statement recognizing the value of a diverse population. The wheel in the photo below is prominently displayed on the first floor of the College of Education at the University of Saskatchewan. This offers another reminder that diverse populations have many cultural subsets of citizens.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Students in schools also represent the societal and cultural subsets within a geographical location. An increased level of diversity offers a compelling reason for educational renewal. Instructional approaches from the past need to be revised to move beyond the ‘one textbook, one workbook, one exam’ approach. For the school curriculum to be effective, students need to see themselves reflected in the curriculum and resources. Students want to be heard, seen, and supported in the classroom.

The final learning module in this language education text supports an inclusive approach to learning known as Culturally Responsive Teaching, or CRT. Another term for CRT is Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP).

What Does ‘Culture’ Really Mean?

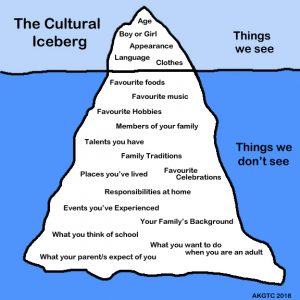

For many people, the word culture is specifically about ethnicity. Authors Helmer and Eddy (2012) explain that culture is not limited to a student’s ethnic background. Cultural affiliations can extend to personal interests, such as music, the arts, sports, or lifestyle. These groups then become the sub-cultures that comprise a student’s unique identity. To illustrate, a high school student can belong to a sports team, a choir, dance group, drama club and debating team. Each sub-culture has its own set of values, expectations, and responsibilities. Therefore, each individual becomes a unique composite of various cultural affiliations. Some cultural affiliations are visible on the surface (e.g., clothing and language), while others are hidden beneath the surface (e.g., talents and heritage).

Source: Permission: CC BY 4.0 Courtesy of A Kids’ Guide to Canada.

A brief video explanation of the term ‘culture’ is available here:

- Cultural Competence Introductory Video. (n/d). SOM Diversity. 3:46 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zcFADtVc5FM

Personal Beliefs and Biases

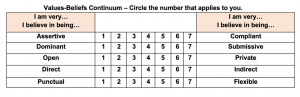

Authors Helmer and Eddy (2012) encourage teachers to reflect on their own cultural values and beliefs by conducting a personal audit. Teachers may not be unaware that they are modeling deeply-ingrained personal beliefs and biases when they set classroom rules or insist on particular practices to be followed.

The authors state that “We all have a basic set of principles that guide how we live, how we interact with others, and those with whom we choose to associate. Within a given cultural group, these principles are often not articulated into a clear focus or creed.” (p. 90).

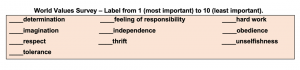

The two audit exercises below were created based on information found in Chapter 7 of the Helmer & Eddy (2012) text Look at Me When I Talk To You. These exercises offer an opportunity to determine which values, beliefs, and characteristics have defined us for many years and may be the source of personal biases.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

A very useful chart of cultural values was created by L. Robert Kohls, Executive Director of the Washington International Centre (in Helmer & Eddy, 2012). The chart compares North American values with values that can be observed among other cultural groups. Kohls’ intent was to help students and visitors to the USA understand societal norms and behaviours in America that might seem puzzling to visitors or newcomers. This chart can be used as an educational tool to spark conversations among staff members about differing values, beliefs, and viewpoints.

The chart is not meant to be interpreted as an either/or list of values. Teachers who represent diverse cultures in North America often find themselves somewhere in between the range of identified values and beliefs.

Values in North America |

Values in Other Cultures |

| Personal control over environment, responsibility | Fate, destiny |

| Change is natural and positive | Stability, tradition, continuity |

| Time and its control | Human interaction |

| Equality, fairness | Hierarchy, rank, status |

| Individualism, independence | Group welfare, dependence |

| Self-help, initiative | Birthright, inheritance |

| Competition | Cooperation |

| Future orientation | Past orientation |

| Action, work orientation | “Being” orientation |

| Informality | Formality |

| Directness, openness, honesty | Indirectness, ritual, saving face |

| Practicality, efficiency | Idealism, theory |

| Materialism, acquisitiveness | Spiritualism, detachment |

Source: Helmer & Eddy (2012) p. 28

What is Culturally Responsive Teaching?

According to Villegas and Lucas (2002), Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT) means that teachers are open to learning about their students’ lives, hold affirming views of diversity, and are willing to advocate for their students. Ladson-Billings (1994) describes CRT as an approach that moves the school curriculum away from superficial celebrations of heroes, holidays, ethnic foods, and national costumes. This approach:

“…integrates a student’s background knowledge and prior home and community experiences into the curriculum and the teaching and learning experiences that take place in the classroom.” Ontario Ministry of Education (2013) Monograph (p.2)

CRT taps into each student’s rich stores of knowledge and diverse perspectives, which are rooted in family language and cultural experiences.

CRT encourages and builds positive attitudes toward student diversity. By infusing school curricula with the principles of CRT, teachers have the ability to reduce attitudes of racism, prejudice, and discrimination. Some ways to infuse CRT into the school curriculum include:

- providing access to multicultural resources;

- opening up dialogues for sharing different cultural practices and beliefs;

- conducting a language audit to see which languages are represented in the classroom;

- posting words/phrases in the languages of families in the school community;

- inviting families to share cultural practices and background experiences;

- encouraging multicultural projects that focus on different cultures and countries;

- raising awareness of global circumstances and efforts to help others in need around the world, particularly after natural disasters or war.

Although language classrooms appear to be a natural fit with the principles of CRT, many language programs continue to follow the ‘one language-one culture’ approach in the classroom. Well-meaning teachers still believe that learning a new language involves an exclusive focus on ethnocultural elements of that language. This type of exclusivity does not reflect or respect diverse cultures in the classroom. By extension, it also reproduces the outdated ‘monolingual principle‘ described by Cummins (2007), which is characterized by three pervading myths:

- Instruction should be carried out exclusively in the target language.

- Translation between L1 and L2 has no place in the teaching of language or literacy.

- Within immersion and bilingual programs, languages must be kept rigidly separate.

Studying a new language can and should involve a focus on building language proficiency, but not at the loss of each student’s cultural identity or background. By infusing a language program with opportunities for students to see how diversity strengthens their local and global community, students become more open to differences in their midst. They will be less afraid of ‘the other’ or the somewhat negative label of ‘foreigners’. Students will come to understand that diverse people around the world give us new approaches to solving common world problems (e.g., environmental issues, global health issues), helping others in need (e.g., natural disasters, world hunger), or advancing global knowledge.

Brief video explanations of CRT and classroom diversity are available here:

- Introduction to Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (2010). 4:39 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nGTVjJuRaZ8

- ClickView (n/d) Wellbeing for children: Identity and Values. 5:03 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=om3INBWfoxY&list=RDLVsQuM5e0QGLg&index=5

How Can Teachers Become More Culturally Responsive?

Culturally responsive classrooms have teachers who set the tone for acceptance of cultural diversity. Teachers become role models who actively display respectful attitudes toward diversity by being honest, open, and genuinely interested in the lives of their students beyond the classroom.

Source – Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain

The language learning classroom, in particular, offers opportunities for students to share their cultures, traditions, language(s), beliefs, lifestyles, and values through an approach known as inquiry-based learning (see diagram above). Inquiry can be used to help students delve into topics that reflect key aspects of their culture and identity. Students can conduct research on any topic of interest using their full repertoire of languages and prior conceptual learning. They can present what they have learned in the classroom, and allow classmates to follow up with more questions or dialogue. Inquiry-based learning allows students to wonder out loud without fear of reprisal or negativity. They search for answers to their questions by consulting credible and reliable sources, using their first language(s) as an additional research tool. Students can investigate, record, discover, think, try, and reflect on their learning, as highlighted in the illustration. The opportunity to share what they have learned with classmates builds oral and written skills in the target language. It is a win-win process for all language learners!

The document Culturally Responsive Teaching (Region X Equity Assistance Center, Education Northwest 2016), offers several best practices for creating a culturally responsive classroom. Some of the recommended practices are listed below.

- Have high expectations for all learners regardless of their background, socio-economic status, or identity.

- Cultivate cross-cultural communication and respect for others.

- Validate the cultural identity of students in the classroom when designing teaching units.

- Gather diverse resources that reflect students’ lives within and beyond the local community.

- Collaborate with educators, administrators, and community members to create a welcoming school environment that embraces student diversity and discourages discrimination.

When teachers create warm, welcoming, and accepting classrooms, this can counterbalance negative attitudes toward those that are perceived as ‘different’ or ‘outsiders’. Negative attitudes that go unchecked often lead to prejudice, bullying, and discrimination.

Brief video explanations of strategies that support CRT are available here:

- Culturally Responsive Teaching and Learning (2011). Genevieve Erker. 8:52 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_uOncGZWxDc

- Competencies for Teaching in Multicultural Classrooms. University of New Brunswick. 7:13 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MwM7kYUGUzA

Review Your Learning

- Define culture as seen through a sociological rather than ethnic lens.

- Describe some personal cultural biases that came to light after conducting a personal audit.

- Identify strategies for building positive attitudes toward cultural diversity in the classroom.

- Explore ways to support cultural inclusivity by using inquiry-based learning in lesson planning.

Module 8 Glossary

Culture: Patterns of behaviour (a way of life) among people who share similar worldviews, beliefs, talents, customs, and values.

Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT): Promotes a proactive approach to honouring cultural diversity by incorporating a student’s background knowledge and prior home/community experiences into the curriculum as part of daily instruction.

Inquiry-based learning: A teaching strategy that offers students the opportunity to learn by exploring their own interests, asking questions, researching topics, and nurturing their natural curiosity.

Monolingual principle: An approach that requires exclusive use of the target language in the classroom to minimize perceived interference from students’ first language(s).

Personal audit: A written or oral survey, checklist, or interview that allows an individual to explore their own strengths and shortcomings.

References

Cummins, J. (2007). Rethinking monolingual instructional strategies in multilingual classrooms. Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. University of Toronto. Retrieved from: https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/CJAL/article/view/19743/21428

Helmer, S. & Eddy, C. (2012). Look at Me When I Talk to You. EAL Learners in Non-EAL Classrooms. Pippin. Don Mills ON.

Ontario Ministry of Education Student Achievement Division. (2013). Culturally Responsive Pedagogy. K-12 Capacity Building Series. Secretariat Special Edition #35. ISSN 19138490.

Queen’s University. (n/d). Inquiry-Based Learning. Centre for Teaching and Learning. Retrieved from: https://www.queensu.ca/ctl/resources/instructional-strategies/inquiry-based-learning

Villegas, A. M., & Lucas, T. (2002). Educating culturally responsive teachers: A coherent approach. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.