Introduction

There are varying opinions about the ‘best’ program model for language learning. In recent decades, the immersion model has been a popular choice for school-aged children in Canada. Yet we know that the immersion model is not possible in many settings, particularly rural settings, due to demographics and limited resources. What other program models and options should be considered for language learning?

Learning Module 3 describes three models commonly used for delivering language instruction in school settings: (a) language as a school subject (b) bilingual education, and (c) immersion education. Of course, languages are also learned outside of school hours (e.g., after-school programs, Saturday schools, summer camps), but the focus of this module is on language delivery during school hours as part of the regular curriculum.

When parents are questioned about their reasons for enrolling children in a language program, one common response is “We want our children to be fluent in another language”. However, the word ‘fluent’ is elusive, meaning different things to different people. What is fluency? Is fluency the same as proficiency? This module examines the meaning of the terms fluency, accuracy, and proficiency and the impact of factors such as place, purpose, and time on language learning.

Program Models: Begin With an Understanding of Proficiency Levels

It may seem strange to begin with proficiency levels rather than moving directly into a description of program models. However, an understanding of proficiency levels informs the selection of a program model in a particular school and location. Consider these questions:

- Is the goal of a language program to provide basic conversational language (BICS) or is the goal to study academic content (subject areas) in the target language (CALP)?

- What is the language background of the learners? Do they have prior experience with the language? (If yes, this may influence the selection of a program model).

- Is there a clear understanding of the stages of language proficiency for assessment of progress?

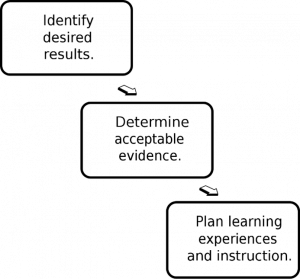

The process of beginning with the end goals in mind (in this case, proficiency levels), is called backward design. Introduced for curriculum development by authors Wiggins and McTighe (Understanding by Design, 2005), the process guides decision-making about program design, delivery, and resources for learning.

Source: Permission: Public Domain.

Determining Proficiency Using A Language Reference Scale

To understanding the meaning of fluency, accuracy, and proficiency, educators must focus on language progression over time, which is comparable to grade-by-grade cumulative progress in one subject area at school. Using language fluently is only one part of the language equation. Using language accurately is the other important indicator of progress. The long-term goal is proficiency, which is a combination of fluency and accuracy.

FLUENCY + ACCURACY = LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY

Fluency describes the spontaneous flow of language without specific attention to language forms, while accuracy focuses on the correct use of a language system, with attention to grammar, pronunciation, and vocabulary. Sometimes a student will speak freely and confidently on many topics, but their speech has many grammatical errors (for example, incorrect case endings, lack of subject-verb agreement, incomplete sentences). This means that the student is speaking fluently but needs support with accuracy. To reach language proficiency, language learners must exhibit both fluency and accuracy in the target language.

As with the term fluency, there is often some confusion with labels such as beginner, intermediate and advanced when referring to language skills. Such terms are subjective and open to interpretation by teachers or administrators. For example, a language beginner may be a student who has:

- no prior experience with the language being learned;

- some knowledge of simple words, phrases, and greetings;

- basic conversational skills in the target language (BICS); or,

- knowledge of the alphabet for reading purposes, without full comprehension.

A language reference scale charts language progress in a cumulative manner, using descriptors of language skills at various stages of learning from absolute beginner to near-native proficiency. A well-constructed, valid and reliable scale illustrates how language students are progressing along a language continuum. The continuum marks stages of language learning that are common across all languages and cultures.

A reference scale can assist language educators to:

- assess the starting point of each student enrolled in a language program;

- create realistic connections between curricular goals and student proficiency levels;

- guide resource selection based on learner skills, comprehension levels, and curricular goals;

- select instructional strategies that build the 4 skill areas: listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

- select assessment strategies that are appropriate for learner language levels

- collaborate with colleagues to improve the progress of language learners at each level of the reference scale;

- create professional networks of language educators across schools, districts, and ministries to support instruction, assessment, and resource development.

Most importantly, a language reference scale provides clear starting points and continual check points for monitoring progress. As students reach higher levels of proficiency in the target language, they transition from conversational language to academic language. The phrase ‘slow but steady wins the race’ aptly describes the language learning process.

A language reference scale confirms that language learning takes time and moves in stages along the language continuum.

The Common (European) Framework of Reference for Languages

For more than a decade, Saskatchewan K-12 schools have used the CFR, or Common Framework of Reference to chart the progress of English language learners in schools. The reference scale is a school-based adaptation of the CEFR, or Common European Framework of Reference (2001) developed by the European Union’s Language Policy Division. The CEFR is a valid, reliable, and research-based reference tool for language learning used in several Canadian provinces and in many countries within and outside of Europe.

The six levels in the CEFR scale, A1 to C2, describe what language learners are able to do in the language(s) they know at each stage of the language learning process. The six levels are divided into four skill strands: listening, speaking (production and interaction), reading, and writing. Language educators can be assured of consistency and objectivity when using the scale to monitor and assess language progress. Global descriptors of all levels are shown below.

Source – Permission: © Council of Europe.

Source – Permission: © Council of Europe.

The adapted CFR document used in Saskatchewan schools has been further sub-divided to create detailed progress descriptors for K-12 language learners at the A1 (A1.1, A1.2), A2 (B1.1, B1.2) and B1 (B1.1, B1.2) levels.

An easy-to-use CEFR/CFR chart with descriptors of what school-aged children know and can do at each stage of language learning is provided in Appendix B of this text. The CEFR/CFR Reference Scale: A Practical Tool for Assessing Language Skills in an Additional Language (Prokopchuk, 2021) can help teachers to monitor learner progress and assign a language level at the end of a term or year of study. Checked descriptors illustrate areas of language progress, while those that remain unchecked will require additional support in the classroom.

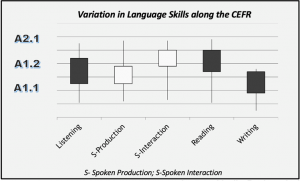

It is rare for students to have equal strength in each of the skill areas of the CEFR/CFR as they learn a language. Given the variability of factors that impact language learning, there is no clear division between levels. Student progress is often jagged or uneven, as shown in the illustration below. An average level can be assigned to indicate each student’s general skill level at the end of the term or course.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Selecting a Program Model: Key Questions to Consider

After a brief examination of the CEFR language reference scale in the previous section, one fact is clear: Students learn language(s) in a cumulative manner over time. There is no ‘quick and easy’ pathway. Students cannot skip stages in the language learning process.

Being aware of the stages of language learning along a reference scale such as the CEFR can help school officials and the school community make decisions about the type of language program that can be offered and maintained in a school district. A few key questions, such as those listed below, can help to inform the decision-making process.

Place (or Location): How does your location impact the choice of language(s) being studied?

- Is there a cultural connection between the target language and the people within a community?

- Are there local resources (e.g., language speakers) to support the language?

- Are there cultural or historic ties to the language in the broader area?

- Is there significant distance between local languages and the language being studied (e.g., different country or continent)? If the answer is yes, why is the language being considered for study at school? Will there be local support for enrolment?

- How does the location impact student motivation, access to learning resources, and the desire to continue language study in the future?

Purpose: Is the purpose (goal) for studying a language communication OR academic study?

- Why is the target language being offered in schools?

- Is the target language being promoted for specific purposes (future job, travel, study, work)?

- Is the goal to promote bilingualism (with students having no choice as to the language of study)?

- Is the purpose linked to a parental request or a government mandate?

- How do students feel about language learning? Will students enrol?

Time: How much time is available for instruction within the school setting?

- How often can the learning take place?

- How large are the blocks of time devoted to language learning?

- Can the learning continue grade by grade, or will there be barriers to continuation (e.g., student enrolment, teacher availability, funding shortages, limited resources)?

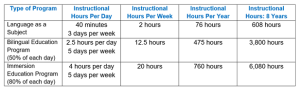

In terms of instructional time, three important factors – amount, frequency, and intensity* – influence and often determine the ability of students to reach higher levels of proficiency.

The chart below illustrates the vast difference in instructional hours available for language learning based on the program model selected in a school or district. Calculations are based on 190 school days and 5 instructional hours per day. This reflects a total of 950 instructional hours per year and 7,600 hours over 8 years (Grades 1-8).

*Intensity – language study compressed into a specific time frame (e.g. bilingual education for one full semester, 6-week immersion block, one full day of language study per week).

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Given the significant difference in the hours of language instruction, language expectations in each type of program must be realistic and proportional to the amount, frequency, and intensity of instruction in the target language. The three models identified in the chart are described in the segment that follows.

Three Program Models

Language as a Subject: When language is studied as a school subject, students attend language class during designated time periods each week. The amount of time available for language as a subject is determined by local school authorities. This model resembles the study of any other subject being learned at school. The language curriculum per grade level is supplied by the ministry or local education authority. It is common for students to achieve conversational language skills (Cummins: BICS) in this type of program.

The Bilingual Program Model: This model, also called dual language education or partial immersion, is defined as “schooling at the elementary and/or secondary levels in which English along with another language are used for at least 50% of academic instruction during at least one school year.” (Genesee, F. & Lindholm-Leary, K., 2008). In this model, students learn the new language while learning content from selected subject areas. Instruction in bilingual education integrates language outcomes with content outcomes in an approach called integrated language and content instruction (ILCI). More information about ILCI appears in an upcoming module.

Immersion Education (Canadian model): As with the bilingual model, students learn a new language through content area study. Canadian French immersion programs are structured to use the target language between 80% and 100% of the school day for most subject areas. In Early Immersion, students begin as a cohort in Kindergarten or Grade One and build language knowledge along a grade-by-grade learning path. Immersion curricula are specifically designed to teach language through content in a cumulative manner. Although Middle Immersion and Late Immersion models are possible, they are difficult to establish due to the logistics of location (gathering students from other schools in a new location) and the language demands on students who do not begin in the primary grades.

Research Supports the ‘Bilingual Advantage’

There is agreement among psychologists, language researchers, and education officials that knowing more than one language has cognitive advantages. Benefits include increased conceptual understanding, flexible thinking, creativity, and executive function (Bialystok 2011, 2017, Marian & Shook 2012).

The Ontario Ministry of Education (2008) uses the term ‘bilingual advantage’ when referring to English language learners in Canadian schools who are speakers of other languages, but are learning English to achieve academic success at school. Ministry officials state that first languages need to be supported by teachers, parents, and the community so that students retain first language skills while becoming bilingual, rather than losing these skills in monolingual classrooms. The quote below from the Ontario Ministry document refers to English language learners; however, the premise is applicable to any language(s) being added to a student’s first language.

Students who see their previously developed language skills acknowledged by their teachers and parents are more likely to feel confident and take the risks involved in learning a new language. They are able to view English as an addition to their first language, rather than as a substitution for it. Respect and use of the first language contribute both to the building of a confident learner and to the efficient learning of additional languages and academic achievement, including: developing mental flexibility; developing problem-solving skills; communicating with family members; experiencing a sense of cultural stability and continuity; understanding cultural and family values; developing awareness of global issues; expanding career opportunities. Students who are able to communicate and are literate in more than one language are better prepared to participate in a global society. Though this has benefits for the individual, Canadian society also stands to gain from having a multilingual workforce.

Supporting English Language Learners (2008), p. 8

According to the Associated Press (2001), there are more bilingual people in the world than monolingual people. More than 60% of the world’s children are being raised as bilinguals. Now more than ever, languages are an essential vehicle for global communication and cross-cultural understanding. Language education in schools can prepare students to live, work, study, and travel in a very interconnected world.

Review Your Learning

- Identify in general terms what students can do at each stage of language proficiency in the CEFR/CFR: A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2.

- Explain how factors such as place, purpose and time influence the type of program model selected for language education.

- List the basic characteristics of three program models for language learning: language as a subject, bilingual education (also called dual language, partial immersion), and immersion education.

Module 3 Glossary

Accuracy: Describes the correct use of a language system, with specific attention to grammar, pronunciation, and vocabulary.

Backward Design: A process that examines the end goals (objectives, outcomes) for a subject or course, and uses these goals as the basis for curriculum design, lesson planning, and assessment.

CEFR/CFR: Acronyms for Common (European) Framework of Reference that refer to a valid, reliable reference scale used to describe language abilities in four skill areas: listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

Fluency: Unrestricted, comprehensible flow of language without specific attention to language forms.

Integrated Language and Content Instruction (ILCI): A dual-focused approach in which an additional language is used for the learning and teaching of both content and language.

Language continuum: A cumulative chart that illustrates the developmental stages of language progress observed across languages and cultures.

Language reference scale: An objective chart that describes observable language skills and abilities along a language continuum.

Proficiency: the combination of language fluency and accuracy, resulting in the ability to use language competently for various purposes and in different circumstances.

References

Associated Press. (2001). Some facts about the world’s 6,800 tongues. Retrieved from: http://articles.cnn.com/2001-06-19/us/language.glance_1_languages-origin-tongues?_s=PM:US.

Bialystok, E. (2011). Reshaping the mind: The benefits of bilingualism. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology. 65(4), pp. 229-35.[10] Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4341987/

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. Strasbourg. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/uses-and-objectives

Genesee, F. & Lindholm-Leary, K. (2008). Dual Language Education in Canada and the USA. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education. Retrieved from: https://www.psych.mcgill.ca/perpg/fac/genesee/21.pdf

Marian, V. & Shook, A. (2012). The Cognitive Benefits of Being Bilingual. In Cerebrum, the Dana forum on Brain Science. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3583091/

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2008). Supporting English Language Learners. A practical guide for Ontario educators. Grades 1-8. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. pp.8-9. Retrieved from: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/document/esleldprograms/guide.pdf

Prokopchuk, N. (2021). The CEFR/CFR Reference Scale: A Practical Tool for Assessing Language Skills in an Additional Language. Chart. College of Education, University of Saskatchewan.

Saskatchewan Ministry of Education. (2013). A Guide to Using the Common Framework of Reference with Learners of English as an Additional Language. Regina: Author. Retrieved from: https://pubsaskdev.blob.core.windows.net/pubsask-prod/82934/82934-A_Guide_to_Using_the_CFR_with_EAL_Learners.pdf

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design. Association for Supervision & Curriculum (ASCD). Virginia: Alexandria.