Introduction

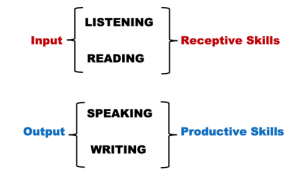

The skills of Listening and Speaking were the focus of the previous module. The remaining two SWRL skills, Reading and Writing, are presented in Learning Module 6.

In each of Modules 5 and 6, one receptive skill was matched with one productive skill, as shown in the image below. Both receptive and productive skills are highlighted in these modules to ensure that all four skills receive balanced attention during the language learning process.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Reading

Two barriers to reading in a new language are (a) decoding and (b) comprehension. Comprehension has been discussed in previous modules and will be reinforced in the current module.

Decoding is the ability to distinguish between letters, sounds, and letter patterns, enabling students to recognize familiar words and to sound out words that are unfamiliar.

When a student demonstrates skill with decoding in a target language, this means that the student has mastered the mechanics or the phonetics of reading letters and their matching sounds. This does not mean that the student also comprehends what is being read; it only means that the student can read with fluency (ease of word recognition, sentence flow, pauses).

Some language students experience challenges with reading. They may have difficulty remembering the sounds of letters, pronouncing the letters, or putting letters together to make words. If this is the case, teachers are encouraged to examine whether the same issues with decoding exist in the student’s first language. Decoding challenges may be a signal of deeper issues with literacy, or this may be a sign of a speech or hearing impairment.

Phonemic Awareness

It is important to pay close attention to the sounds of a new language. However, it may not be possible for some students to pronounce letters and words in exactly the same manner as native speakers of the language. Pronunciation in English, for example, is impacted by first language phonemic distance from English, the number of hours spent learning the language, the age of learners, and individual oral adaptability. In some cases, the cause may be a physical impairment with the tongue. Note the following quote from Gibbons (p. 170):

“The phonemes of different languages are rarely exactly the same, although many phonemes in the student’s first language may be close. This means that for English language learners, their own languages will not match all the sounds in English, and vice versa. Most language learners, especially in the early stages of learning the language, make use of the closest sound in their own language when the English phoneme is unfamiliar (and they probably “hear” it as the sound in their own language, too).

Gibbons (2015), p. 170

The general consensus among language educators is that accents should not be considered problematic unless pronunciation is impeding comprehension of oral language and/or negatively affecting development of reading and writing skills in English.

An infographic titled What are the Hardest Languages to Learn (Source: Voxy) can be viewed here: https://voxy.com/blog/hardest-languages-infographic/. It presents an interesting perspective on the number of hours an English speaker typically needs to learn another language. While not grounded in academic research, the infographic is thought-provoking because it separates languages into three distinct categories based on language distance. The concept of language distance will be discussed in greater detail in an upcoming module.

Fluency vs Accuracy in Reading

As mentioned previously, fluency is a focus on mechanics: the combination of letters, patterns, and blends to create specific sounds, leading to word recognition. However, a native speaker will also know how to read accurately, with proper points of emphasis, stress, and intonation. This requires a deeper understanding of context in the target language. One distinct clue that a reader does not comprehend what is being read is the lack of accuracy when reading.

To emphasize this point, if a reader is proficient in English, the words in the sentences below will be read with both fluency and accuracy (Source: Coelho, 2016, p. 60).

- We polish the Polish furniture.

- A farm can produce produce.

- The soldier decided to desert in the desert.

- The dove dove into the bushes.

- The insurance for the invalid was invalid.

- The bandage was wound around the wound.

- They were too close to the door to close it.

- The wind was too strong to wind the sail.

- I shed a tear when I saw the tear in my clothes.

- I spent last evening evening out a pile of dirt.

However, if a reader is limited to decoding skills, the sentences may not be read accurately. Accuracy requires a broad range of vocabulary and background knowledge in English. In other words, the input must be comprehensible to the student. A fluent reader will easily read the words, but an accurate reader will read the statements with the correct sentence stress and accenting on words that look alike, but require different pronunciation. A fluent and accurate reader has a high level of proficiency in the target language as evidenced in the reader’s comprehension of vocabulary and contextual meaning.

An example of the power of comprehension for proficient readers is shown below.

I cnduo’t bvleiee taht I culod aulaclty uesdtannrd waht I was rdnaieg. Unisg the icndeblire pweor of the hmuan mnid, aocdcrnig to rseecrah at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it dseno’t mttaer in waht oderr the lterets in a wrod are, the olny irpoamtnt tihng is taht the frsit and lsat ltteer be in the rhgit pclae. The rset can be a taotl mses and you can sitll raed it whoutit a pboerlm. Tihs is bucseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey ltteer by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe.

Source: Google Images

Proficient readers will be able to unscramble the letters to determine the words in each sentence. Research (at the university named in the text) illustrates that even if words are misspelled or letters are scrambled, proficient readers can decode the message due to their knowledge of vocabulary and ability to pick up contextual cues in the text.

Before-During-After Reading Strategies

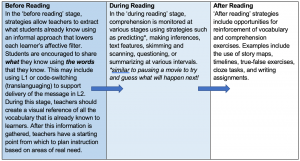

Gibbons (2015) and other language specialists consider before-during-after reading strategies to be the most effective means of introducing, explaining, and reinforcing vocabulary. These strategies ensure a high level of comprehensible input, so that students can read and comprehend texts in a new language. This is particularly important for students learning subject area content in a new language. A summary of before-during-after strategies is given below.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

In general, reading skills are enhanced by the use of the following strategies:

- brainstorming, explicit instruction, word walls, language experience charts, graphic organizers, visuals (photos, props), questions, interviews, sequencing tasks, choral reading, small-group reading, guided reading.

Electronic tools can be particularly helpful when introducing a topic, recalling prior learning, or reinforcing concepts between L1 and L2. Some examples of online tools are:

- news clips, audio/video recordings, online textbooks, online dictionaries, Wikipedia, informational emails, online library resources (particularly dual language books).

Before-during-after reading strategies explicitly target vocabulary building, but teachers are ultimately responsible for selecting and adapting appropriate reading resources and strategies to suit the age, prior knowledge, and language proficiency level of the learners in class.

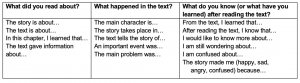

Practicing an after-reading strategy that uses a three-step pattern can be especially helpful when reviewing the content of a subject-specific text. Samples of questions and frame sentences are shown below.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Other samples of after-reading questions can be downloaded from Mercer Island Schools Mondo Bookshop, Grade 4. PDF.

Brief video explanations are available here:

- University of New Brunswick. (2019). Intentional Vocabulary Instruction L2RIC. 6:24 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rXlkTMmXOZU

- University of Toronto (OISE). Before, During, and After Reading Comprehension.The Balanced Literacy Diet. 5:45 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sd1FlXxpVIw

- Oxford University Press ELT. Reading Effectively: A 3-Stage Lesson Guide. 4:29 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xh8M_x57pa4

Using Authentic Materials and Texts

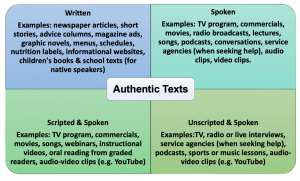

There is a pervading myth that authentic materials are too difficult for language learners and should therefore be avoided as resources in the classroom. In their book Authentic Materials Myths, authors Zyzik & Polio (2017) describe authentic materials as “…those created for some real-world purpose other than language learning, and often, but not always, provided by native speakers for native speakers.” The definition indicates that materials were not created for language learning, but rather, to communicate something of value to native speakers. However, the materials provide a culturally-appropriate, real-world example of how the language is used by native speakers. For this reason, authentic materials are a rich source of support for language learners. In their book, Zyzik & Polio share many ideas for practical ways to incorporate authentic texts into the language learning classroom.

Authentic texts can be divided into 4 categories: written, spoken, scripted and unscripted (Zyzik & Polio, 2017). Each category contains texts that can be useful for language learning, if teachers take time to use pre-during-post reading strategies to ensure that language is comprehensible.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Supplementary video clips to support this topic are available here:

- American English. (n/d). Task-based Reading Activities Using Authentic Materials & Skills. 3:27 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eXPzKa2_-y4

- Storyline Online (2022). English stories/books read aloud by various actors. SAG-ACTRA Foundation. https://storylineonline.net/

The CEFR/CFR and Reading

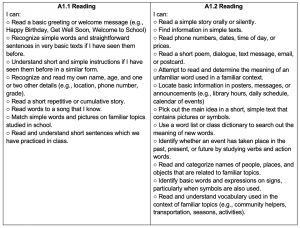

A review of the Reading Descriptors found in the CEFR/CFR chart (Prokopchuk, 2021), available in Appendix B, provides a comparative look at skill progression in reading.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan.

The verbs used in the second column of descriptors illustrate progress with both reading and comprehension. For example, at A1.1, a student can ‘match simple words and pictures on familiar topics’. With more practice and support, in level A1.2 the student can ‘read and categorize names of people, places, and objects’.

Writing

According to Gibbons (2015, p. 144), a principle of good teaching is “…to go from what students already know to what they don’t yet know, to move from the given (already known) to the new (what is yet to be learned)…” Therefore, when encouraging language learners to write, they should move from ‘the known to the new’. A thorough scan of known vocabulary and visible/accessible word banks of new vocabulary should be part of the instructional process. The following questions can guide classroom planning for writing activities:

- Is there an opportunity for students to ‘show what they know’ by visual representation if they have not yet learned enough vocabulary in the target language?

- Is there a plan for introducing new vocabulary that offers opportunities for students to access L1 as a link to prior learning?

- Does the selected strategy expand learner knowledge of vocabulary?

- Within the strategy, is there an opportunity to list, define, and record vocabulary for future reference (e.g., personal word journal, word walls, class dictionary)?

- Does the student have (access to) information about grammatical rules?

- Is this genre appropriate for the language learning process at this time?

Explicit, Age-Appropriate Instruction About Grammar

Many linguists agree that students require explicit instruction about the rules of a language in order to help them achieve language proficiency. In her book Adding English (2016, p. 170), Coelho states:

“Most students require a certain amount of explicit instruction to help them figure out some of the rules of English grammar. The older students are, the less likely they are to intuitively pick up the patters of English and the more formal instruction they may require. Even young children and beginning learners of English can understand the concepts “one” and “more than one” when learning the plural endings of nouns, such as books…”

Coelho (2016), p. 170

Grammar instruction is most effective when it focuses on patterns of language use in meaningful contexts. Isolated drills and practice lessons without some type of practical context has been shown to be ineffective (e.g., Grammar-Translation Method). Students are often unable to reproduce the patterns or remember the rules in spontaneous, real-life situations.

Language learners of all ages benefit from explicit instruction about rules. The instruction must be developmentally-appropriate and based on language that is meaningful to students. Young learners often need appropriate examples, predictable order, and multiple exposures to the rules of the language. Formal instruction will not be effective at certain ages and stages of learning. For example, young language beginners will not benefit from a lesson on subject-verb agreement if they have not yet learned the meaning of the words ‘noun’ and ‘verb’.

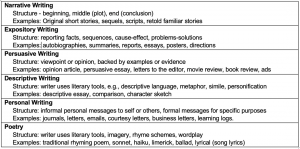

Writing Genres

Genres encompass a broad range of writing types as shown in the chart below. This chart is certainly not exhaustive, but it conveys the expansiveness of writing genres. Within these genres are also sub-types such as fiction (fantasy, science fiction, historical fiction) and non-fiction (informational writing, autobiography).

Understanding imagery, figurative speech, or literary language in certain genres (e.g., poetry, fantasy) can be problematic for language learners. Imagine the depth of language required for a non-English speaker to read and comprehend a chapter in one of the Harry Potter books (Author: J. K. Rowling), followed by a written assignment based on the reading! This would be a daunting task.

Teachers need to consider the language level, purpose, and goals of their program before expanding their use of genres.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

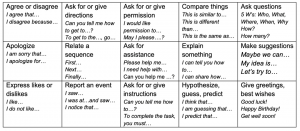

Best Practices for Writing

When language teachers ask students to write for a specific genre, they may need to provide sentence frames to help students complete the function or tasks. Sentence frames can be displayed in wall charts or recorded in each student’s personal journal.

Some examples of sentence frames (in italics) are provided in the chart below, organized by language functions.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

In general, writing skills are enhanced by the use of the following strategies:

- a print-rich environment, explicit instruction, word walls, graphic organizers (timelines, flow charts, webs, Venn diagrams, tables, other types of organizers), illustrations, picture prompts, cloze technique, sentence frames, paragraph frames, and story-starters.

As with reading, electronic tools can also be used to support writing. Examples of online tools that support writing assignments are:

- news clips, audio/video recordings, online textbooks, online dictionaries, Wikipedia, informational emails, online library resources (particularly dual language books).

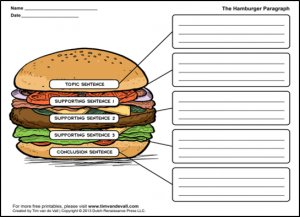

Students may also need help constructing a well-written paragraph in the target language. The illustration of a ‘paragraph frame’ provided below is commonly used in schools to explain the components of a well-written English language paragraph. Students certainly remember the image of a hamburger with multiple layers! The number of supporting sentences is flexible (not limited to 3).

Source – Permission: Copyright © 2022 Tim’s Printables.

In the video presentation titled Scaffolds for Writing (2011), Elizabeth Coelho offers a simplified explanation of the paragraph frame pictured above, using three statements: “This is what I know” (topic sentence); “Here is some evidence to show what I know” (supporting sentences); and, “Now you should believe me” (concluding sentence). In this same video presentation, Coelho adds a valuable explanation of an effective strategy for language learning known as cloze. The Coelho video clip is available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WdvXJ1GsSkk .

The CEFR/CFR and Writing

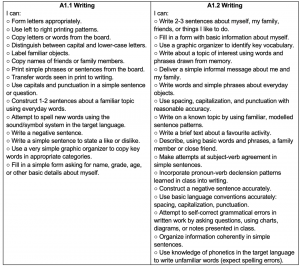

A comparative look at the Writing Descriptors in the CEFR/CFR chart (Prokopchuk, 2021), available in Appendix B, illustrates how writing skills progress during the earliest stages of language learning.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

The descriptors in the second column illustrate a growing level of writing ability. For example, in the beginning stages of writing in a new language at A1.1, the student can write one or two sentences about a familiar topic. As writing skills progress at A1.2, the student can write a brief text about a favourite activity.

To Sum Up: Create a Toolkit of Vocabulary-Building Strategies

Many strategies and resources have proven to be effective for skill-building in the areas of listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Recall that Cummins separated vocabulary into two types: communicative (BICS) and academic (CALP). Communicative vocabulary is easier to establish and can be gained in a relatively short time, while academic vocabulary requires more time and strategic support. For this reason, language teachers are encouraged to create a toolkit of effective strategies that target academic vocabulary. Language specialist Kate Kinsella (2017) uses the term high-utility academic vocabulary to describe a collection of words and phrases that appear frequently across a wide range of subject areas.

Kinsella states that school success for language learners is dependent on ‘owning’ a broad base of high-utility academic vocabulary. According to Kinsella, students “must recognize a critical mass of vocabulary and be able to competently deploy a toolkit of high-utility academic words they clearly own”. Owning words means that students understand and can accurately use a broad base of vocabulary to articulate thoughts, provide oral responses, or complete assignments on academic topics.

High utility academic words differ from words used in conversational language. Many of these words have Greek or Latin roots that have been shared around the world to discuss the sciences, mathematics, medicine, business, or technology. As such, the words sound very similar and can easily be understood in academic circles. Words that are derived from a common root word and sound similar across two or more languages are called cognates. Some examples of cognates are information, computer, astronomy, and biology.

To illustrate how high-utility words can be infused into classroom language, a common phrase such as ‘Let’s think about this’, can be replaced with ‘Let’s consider this perspective’ or ‘Let’s analyze this’. The terms consider, perspective, and analyze are useful and transferable across subject areas. The words ‘perspective’ and ‘analyze’ are also cognates in a number of languages, such as French, Spanish, Ukrainian, Portuguese, and German.

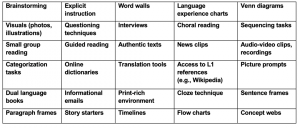

If classroom language teachers feel at a loss for where to begin when lesson planning and building high-utility vocabulary, the chart of possibilities shown below can be used with confidence. The chart is not comprehensive; other strategies may be added to this collection.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Review Your Learning

- Clarify the difference between ‘reading fluently’, ‘reading accurately’ and ‘reading with comprehension’.

- Refute the myth that authentic materials are not suitable for use in the language classroom.

- Explain the rationale for age-appropriate explicit instruction about grammatical rules to support writing in a new language.

- Select and describe five reading and writing strategies that are effective for language learning in a classroom setting.

Module 6 Glossary

Authentic materials: Texts and other resources that target real-world purposes other than language learning, usually created by native speakers for native speakers.

Before-during-after reading strategies: A series of strategies that support comprehension of reading material by a) eliciting prior knowledge and introducing key vocabulary before a text is read b) supporting vocabulary growth and comprehension during reading, and c) reinforcing vocabulary and learning material from the text after reading.

Cognates: Words that are derived from a common root word and sound similar across two or more languages.

Decoding skills: Describes the ability to distinguish between letters, sounds, and letter patterns, enabling students to recognize familiar words and figure out words that are unfamiliar.

High-utility academic vocabulary: Frequently occurring words used across a wide range of subject area topics for academic learning.

Writing genres: Various types of literary writing created within a culture by members of that culture for a social purpose.

References

Coelho, E. (2016). Adding English. A Guide to Teaching in Multilingual Classrooms. Second Edition. University of Toronto Press.

Gibbons, P. (2015). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning. Teaching English Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom. Second Edition. Heinemann. Portsmouth NH.

Kinsella, K. (2017). Helping Academic English Learners Develop Productive Word Knowledge. In Language Magazine. Retrieved from: https://www.languagemagazine.com/2017/03/17/helping-academic-english-learners-develop-productive-word-knowledge/

Prokopchuk, N. (2021). The CEFR/CFR Reference Scale: A Practical Tool for Assessing Language Skills in an Additional Language. Chart. College of Education, University of Saskatchewan.

Zyzik, E. & Polio, C. (2017.) Authentic Materials Myths. University of Michigan Press.