Introduction

The Wiggins and McTighe (Understanding by Design, 2005) planning model shared in the previous module, called backward design, helps instructors to plan lessons by beginning with the end in mind. Viewed through the lens of the K-12 curriculum, this means that lesson planning should begin with a focus on curriculum objectives, or the ‘results’ of the learning. Backward design involves three steps:

- Identify the desired results. What will students know and be able to do at the end of the unit, course or term?

- Determine acceptable evidence of progress. What methods will be used to assess learning? How will students demonstrate their language learning?

- Plan learning experiences and instruction. What tasks, activities, or resources will help students to learn the target language?

When working with language learners, the success of lesson planning is dependent on knowing the language abilities of students at the start of the instructional program.

- What do students already know and what can they do using the target language?

- Are students absolute beginners or do they have some prior knowledge in the target language?

- How will a range of language skills affect planning for differentiated learning tasks?

- How will this affect resource selection?

This module proposes that teachers begin the backward design process with one additional step: initial assessment of language skills. Language specialist Elizabeth Coelho (2012) recommends a step by step process for initial assessment, outlined in the module, to provide teachers with a clear snapshot of the language abilities of students in the classroom. Once initial assessment is complete, teachers can plan lessons that more closely align with each student’s prior knowledge, comprehension levels, and language abilities. Instructional resources and tasks can also be selected strategically to help students expand language skills in listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

Research in language education points to significant benefits when language is learned through content instruction. This requires that language objectives be written to match content objectives referred to in the first step of the backward design process. Instructional planning that considers both language objectives and content objectives improves classroom progress with language learning. According to Genesee (1994), a leading researcher in immersion and second language education:

- Instructional approaches that integrate content and language are likely to be more effective than approaches in which language is taught in isolation.

- The use of instructional strategies and academic tasks that encourage active discourse among learners and between learners and teachers is likely to be especially beneficial for second language learning.

- Language development should be systematically integrated with academic development in order to maximize language learning.

Source: Coelho (2012) Ch.3, p. 71.

Initial Assessment: A Snapshot of Language Skills

Conducting an initial assessment helps to determine each student’s language proficiency in the target language at the beginning of a language program. The results offer a snapshot that acts as a baseline starting point from which all language progress can be assessed throughout the year. Initial assessment can be very revealing! Comments such as “We thought they remembered more from last year” or “Although the students read fluently, many don’t understand the content” are common.

One of the major strengths of the initial assessment process is the collaboration that can take place between language teachers and grade-level teachers. A clear picture of each student’s academic capabilities emerges. The language teacher then documents a student’s language level using a reference framework such as the CEFR (explained in the previous module), and then makes decisions about how to structure lesson plans that will help language students achieve the course objectives. Planning takes place with teachers fully informed about language strengths and areas that need support.

Coelho outlined a comprehensive sequence of activities for initial language assessment in her book Language and Learning in Multilingual Classrooms (2012). Originally designed for English language learners in schools, Coelho’s process of initial assessment is applicable to all language learners (Chapter 2, pp 28-31). The steps below are an adaptation of Coelho’s original sequence for English learners.

STEP 1: WRITING AND READING SKILLS

(A) Ask the student to label a picture in the target language.

- If the student can label the picture, ask the student to write a few sentences or paragraphs to introduce themselves, describe a favourite place, describe the picture, or retell an important event.

- Take note of the following: How long does it take the student to produce the piece of writing? Does the student check and edit the piece? How simple or complex is the language used in the writing?

(B) Offer a few samples of text to determine the range of reading abilities.

- Allow the student to select the text that they are comfortable reading aloud.

- Ensure that samples reflect a range of reading levels and interests, e.g., basic greetings, friendly conversation, informational text, poetry, and an excerpt from a novel.

- Provide a few minutes for preparation.

This is not meant to be a comprehension exercise; rather, you will learn something about the student’s familiarity with print, ability to decode, place stresses on the correct parts of words or phrases in sentences, and read aloud with confidence and fluency.

STEP 2: ORAL SKILLS – INFORMAL INTERVIEW

Proceed to this step only if the student has some basic oral language skills.

- Ask simple, open-ended questions to get a sense of the student’s conversational skills. Make note of the student’s fluency, pronunciation, accuracy with grammar and word choice, and overall ability to communicate effectively. Sample questions might be:

- What is your name?

- How old are you?

- Where do you live?

- What are the names of your parents?

- Do you have grandparents (or a favourite aunt or uncle)? What are their names?

- What is your favourite movie (or song, book, or app)?

- Tell me about your last birthday (or family gathering). Did you have a party?

- Do you play sports (or take dance lessons, music lessons, other lessons)? Tell me something about your hobby.

STEP 3: ORAL SKILLS – PICTURE PROMPT

Proceed to this step only if the student was able to participate in Step 2.

- Provide a set of pictures showing people of various ages involved in different activities.

- Ask the students to select a picture and to talk about what they see. Some students might point and name objects in the picture, while others might describe the picture. Students with greater oral fluency may be able to tell a story, using the picture as the starting point or the ending.

STEP 4: WRITTEN SKILLS

Proceed to this step only if the student was able to complete Step 1(A). If the student has no experience with writing in the target language, you will need to adjust lesson plans accordingly for this student.

- Ask the student to write about the picture they selected. Some students will be able to label a few items, while others may be able to write sentences or a descriptive paragraph. Students with greater levels of fluency may be able to create a story about the picture.

- Offer a bilingual dictionary and see whether students make use of it (if age-appropriate).

- When assessing the writing, use a holistic approach. First, consider the writer’s age, level of detail in the writing, organization of thoughts, and flow of information. Then consider vocabulary, grammar, spelling, and punctuation.

STEP 5: READING COMPREHENSION

- Provide a selection of short reading passages with age-appropriate content and at various levels of difficulty.

- Ask the student to choose a passage and read it silently.

- Ask the student to talk about what was read. You can provide prompts or ask questions to encourage the student to retell or summarize the content.

- Ask students to connect the passage to their own prior knowledge (e.g., Have you ever seen…? Has this happened to you? When?)

- Proceed to more challenging questions involving analysis, inference, or synthesis (What would you do if…? Do you think that…? What might happen next?)

- If the student is able to talk about the content quite easily, encourage the student to try a more challenging reading passage.

- If you have time limitations, a quiz format could be used with students, e.g., true-false questions, matching, fill-in-the-blank, short answer questions.

After conducting an initial assessment, teachers will be able to check some of the “I can” statements found in the CEFR/CFR chart of descriptors (N. Prokopchuk, 2021) found in Appendix B of this text. Most teachers agree that the knowledge gained through the initial assessment process is invaluable to lesson planning.

Language Learning Through Content Instruction

The early success of bilingual and immersion models resulted in an increase in research on the process of learning language through content. Researchers Genesee (1994) and Met (1998) recognized that content gives language learning meaning and purpose. Language becomes the vehicle for learning school-based topics.

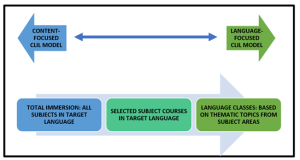

The positive effects of this combination resulted in a gradual shift from the Communicative Approach to an approach called Content-based Instruction, CBI (also known as Integrated Language and Content Instruction, or ILCI, introduced in the previous module). The approach describes language teaching that shifts the focus away from the language itself to content (linked to school subjects) that can be learned in the target language. Met (1998) characterized this gradual shift as a movement toward a content-driven rather than language-driven approach.

The European variation, called Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), proposed that the traditional language and grammar approach used to study foreign languages be changed to a content-driven approach. The ‘content-language continuum’ emerged as a new model for language learning (The CLIL Guidebook v.2, 2021).

Adaptation: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan. Based on: Attard-Montalto, S., & Walter, L., (2021). The CLIL4U Guidebook v.2 2021, (p. 38).

Brief video clips to extend your understanding are available here:

- Presentation by J. Alberich. (n/d) CLIL – A Brief Introduction 1:32 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uIRZWn7-x2Y

- Explained Simply. (n/d). CLIL – Content & Language Integrated Learning 4:37 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2h33LnIqR1c

- CLIL4U Swiss Project. (n/d). Six Videos Demonstrating CLIL. 14:15 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dFuCrxRobh0

- CLIL 4U Main Website. (n/d). https://languages.dk/clil4u/

Language Objectives: A Focus on Academic Language

Educators are familiar with content objectives, which are statements that define what a student is expected to know, understand, and be able to do at the end of each grade, unit, or specific course of study. In K-12 education, content objectives are the end goals of subject-area curricula at each grade level.

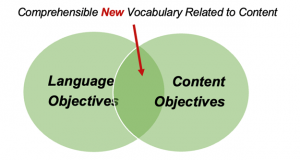

Language objectives (in relation to content area teaching) are a more recent construct. Language objectives present the academic language required to achieve content objectives. Well-constructed language objectives complement the knowledge and skills identified in content objectives. Language objectives combined with content objectives can benefit all students in K-12 education, not just those learning an additional language.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

When language objectives are infused into the study of content from various subjects, students become engaged in learning the target language through the real-world environment of the classroom. In other words, language learning has a function and a purpose. Real communication is taking place for real purposes in the classroom to achieve course and grade-level objectives.

Coelho (2012, p. 73) identifies several features of ILCI that make it successful, such as: attention to comprehension in the new language, more opportunities for interaction, purposeful learning tasks linked to mainstream curriculum, and attention to forms and functions used naturally in a classroom context.

Writing Language Objectives that Align with Content Objectives

Now that we know why the combination of language and content objectives is important, how do we create language objectives? The acronym SMART is helpful when creating objectives, to ensure that they are specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-based.

Source – Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Dungdm93

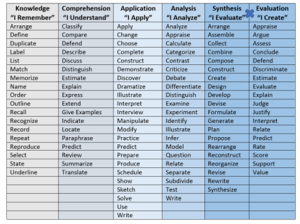

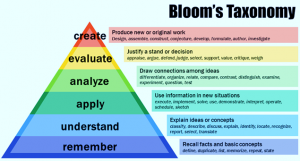

One proven way to ensure that language objectives are well-written is to use verbs that are specific and measurable (observable), linked to the four skill areas: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. To ensure that verbs are not limited to simple or lower-level cognitive tasks for language learners, (e.g., list, retell, categorize, read), the verbs should also reflect a range of tasks that tap higher levels of thinking along Bloom’s Taxonomy.

The two images that follow contain verbs that support the creation of language objectives.

NOTE: The first image represents the updated 2001 version of the taxonomy with upper levels labeled as ‘evaluate’ and ‘create’. The second table of verbs represents the original categories of Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956), with the upper levels being Synthesis and Evaluation. There is clearly some overlap between the upper levels in both versions of the taxonomy.

Source – Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching

Chart Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan. A more comprehensive list of verbs may be found here: Utica University PDF

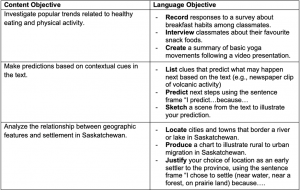

Examples of Language Objectives Aligned with Content Objectives

Chart Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Try it! Write language objectives to match one of the content objectives below. Hint: Focus on the verbs.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Review Your Learning

- Describe some ways to conduct an initial assessment to document a student’s language skills in listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

- State the benefits of writing language objectives to correspond with content objectives linked to the school curriculum.

- Demonstrate your ability to write language objectives that correspond to content objectives linked to the levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Use one or two content objectives from your own school curriculum for this task.

Module 4 Glossary

Bloom’s Taxonomy: A hierarchy created by Benjamin Bloom in 1956 (revised 2001) to present six stages of observable actions that tap higher levels of thinking and increased cognitive activity.

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): A dual-focused approach in which an additional language is used for the learning and teaching of both content and language.

Content based instruction (CBI): An approach in which students learn the language in real-world contexts using subject matter that is important or relevant to their needs.

Content objectives: Statements that indicate what a student is expected to know, understand, and be able to do at the end of each grade, unit, or specific course of study.

Initial assessment: Involves a series of steps that help to determine a child’s language proficiency in the target language at the beginning of a language program.

Language objectives: Target the vocabulary required to comprehend subject matter and achieve the content objectives.

References

Attard-Montalto, S. & Walter, L. (2021). The CLIL Guidebook v.2. A Gateway to CLIL & Technology-Enhanced Scaffolded Learning. Council of Europe and the Erasmus Centre. Retrieved from: https://languages.dk/archive/clil4u/book/clil%20book%20en.pdf

Coelho, E. (2012). Language and Learning in Multilingual Classrooms: A Practical Approach. Multilingual Matters. Bristol.

Genesee, F. (1994) Integrating Language and Content: Lessons from Immersion. In Educational Practice Reports. No 11. National Center for Research on Cultural Diversity and Second Language Learning. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Met, M. (1998). Curriculum decision-making in content-based language teaching. In J. Cenoz & F. Genesee (Eds)., Beyond bilingualism: Multilingualism and multilingual education (pp. 35-63). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Prokopchuk, N. (2021). The CEFR/CFR Reference Scale: A Practical Tool for Assessing Language Skills in an Additional Language. Chart. College of Education, University of Saskatchewan.

Utica University. (n/d). Bloom’s Taxonomy of Measurable Verbs. New York. Retrieved from: https://www.utica.edu/academic/Assessment/new/Blooms%20Taxonomy%20-%20Best.pdf

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design. Association for Supervision & Curriculum (ASCD). Virginia: Alexandria.