Introduction

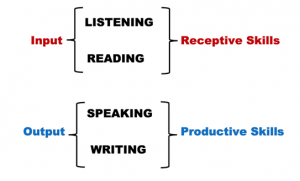

The next two modules focus on the four skill areas for language learning: Listening, Speaking, Reading and Writing.

The ‘swirled’ line drawing below offers a visual representation of the acronym SWRL, used by some language experts to represent the four skill areas.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Authors Cohan, Honigsfield & Dove (2020) prefer to use SWIRL, which specifically mentions Interaction (two-way) as an extension of Speaking (one-way). Whether you use SWRL or SWIRL, the purpose of the acronym is to highlight the equal importance of receptive skills (listening and reading) and productive skills (speaking and writing). Krashen referred to receptive skills as input, while Swain labelled the productive skills as output.

This module discusses ways to enhance listening and speaking skills in the language classroom. Several strategies that encourage student talk in the classroom will be shared.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Listening

In the book Scaffolding Language, Scaffolding Learning, Pauline Gibbons (2015) states that “The teaching of listening is often assumed to ‘happen’ in the process of the teaching of speaking or reading; teaching programs often refer to ‘listening and speaking’ as a single unit, so the specific teaching of listening may be overlooked.” (p. 183). Gibbons believes that the process of listening is very similar to the process of reading in that both skills involve a high degree of comprehension to be meaningful.

During the listening process, the listener needs to focus intently on incoming messages. The idea of visualizing what is said while it is being said (much like creating an audiovisual clip in your head) can be helpful. Gibbons states that “…your ‘in-the-head’ knowledge allows you to map key words onto the words you are hearing, and therefore predict meaning.” (p. 185). If the incoming text is too difficult, the listener sinks rather than swims in a sea of new words. There is no prior ‘in-the-head’ knowledge that can be linked to the new messages. Without a firm base of prior knowledge, the meaning of new words cannot be predicted, and the message carries no meaning for the listener.

To understand the role of context while listening, imagine that a colleague is telling a story in the staff room about a recent plane trip that did not go smoothly. Your colleague is speaking about air turbulence, oxygen masks falling during the flight, and a lack of in-flight service. The full impact of this story is understood more clearly if others in the staff room have had the experience of flying. For those who have never flown, it will be difficult to listen and comprehend why this colleague was distraught about air turbulence, oxygen masks, and in-flight service. These terms carry meaning in the context of air travel. Only those colleagues who have travelled by plane will literally be able to ‘picture the scenario’ while their colleague is relating the situation.

Source: Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Lord of the Wings

Our Noisy World

Is it common for teachers to take time to teach the skill of listening to support learning? Have you ever taken time to focus on listening with your students? The answer is likely no. We make the assumption that students come to class ready to listen and learn.

Today’s world is filled with noise. Unfortunately, we have all grown accustomed to the noise and may choose to ignore important pieces of information being shared by others. Students (and many adults!) have learned to practice selective listening amidst this noise. They choose to listen only to what interests them or what is relevant to their needs, while actively ignoring other incoming information. In fact, social media apps have become successful largely due to algorithms that detect each person’s selective listening and reading interests. Background mechanisms built into the apps de-select other topics or noteworthy items. A user’s newsfeed is then saturated with pre-selected items based on the user’s search history. The user is drawn into selective listening, viewing, and reading through these algorithms.

Brief video explanations are available here:

- TED Talk: 5 Ways to Listen Better. Speaker: Julian Treasure 7:50 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cSohjlYQI2A

- Career and Life Skills Lesson: Listening Skills – Active Listening 4:48 min.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Al3NfpVJl-U

The CEFR/CFR and Listening

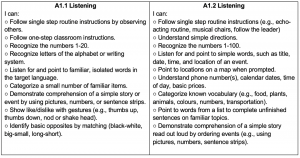

The CEFR/CFR reference scale identifies listening as one of four distinct skills for language learning. It is helplful to spend some time reviewing the Listening Descriptors found in the CEFR/CFR chart (Prokopchuk, 2021), available in Appendix B.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

The descriptors in each column illustrate a growing level of comprehension. For example, a beginner student begins by following one-step classroom instructions (A1.1) but is soon able to understand simple directions (A1.2). This means the student has made progress with language comprehension and listening skills.

Speaking (Oracy)

When creating lesson plans, teachers are encouraged to take a step back and view the topic, the vocabulary and reading materials through the eyes of a language learner. Where might the students experience the greatest challenge with comprehension? Which vocabulary has been taught previously in class and will be understood by students? Which words are new? Can the students use the vocabulary confidently?

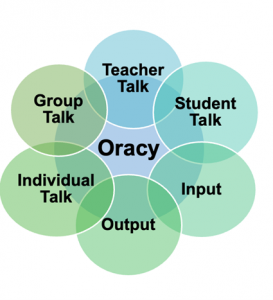

Classroom talk is a term used to describe a balanced approach to teacher talk, student talk, individual and group talk in the classroom. Each type of ‘talk’ requires comprehensible input (teacher talk) and many opportunities for output by students. Selecting strategies that allow students to practice their speaking skills may seem challenging (particularly in large classrooms) and time is in short supply! However, it is possible to plan strategically and support each student’s oral language progress in the target language.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

You will recall from a previous module the terms comprehensible input, the Goldilocks Rule and the Five-Finger Rule. These terms drew attention to the number of unfamiliar words encountered by a language learner. To ensure that input is comprehensible, teachers can lessen the language load by reducing the number of new words in a lesson using strategies such as:

- revising or simplifying the language in learning materials;

- using visuals or graphic organizers to aid comprehension;

- presenting information in short, comprehensible chunks;

- pre-teaching key vocabulary; or

- using a pre-during-post teaching strategy to ensure comprehension of oral or written text.

Output is central to the language learning process. To enable output, students must become active participants in the communication process by asking for repetition or clarification (e.g., Can you repeat, please? Can you explain?), making gestures (e.g., raising hands and shoulders for “I don’t understand”), making a drawing, pointing to a symbol, paraphrasing, or using circumlocution, which means talking around a topic using known words when key terms are unknown. In the example shown below, the student cannot remember the word ‘winter’. The teacher sparks the student’s memory using two different prompts.

Teacher: What season comes after fall?

Student: The season that comes after fall is… very cold.

Teacher (Prompt 1): Which season is very cold?

Student: After fall it is very cold and there is snow.

Teacher (Prompt 2): Repeat after me: Spring, Summer, Fall, and …

Student: Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter!

Teacher: What season comes after fall?

Student: The season that comes after fall is winter.

The term circumlocution goes hand in hand with Merill Swain’s phrase stretched language. Swain (2000), a noted Canadian linguist, describes this as language that is somewhat unfamiliar to the learner but is used within a conversation in an experimental fashion to convey a message. “You are pushed to go beyond the language you can control well and to try out ways of saying something that requires you to use language you are still unsure of, probably using faulty grammar or inaccurate vocabulary” (Gibbons, 2015, p. 26). Using the example above, the student’s attempt at stretched language is highlighted.

Teacher: What season comes after fall?

Student: The season that comes after fall is… very cold.

Teacher: Which season is very cold?

Student: After fall it is very cold and there is snow. Outside is very white, snow is crunchy like sugar. So cold…temperature is minus.

Teacher: That is true! Repeat after me: Spring, Summer, Fall, and …

Student: Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter!

Teacher: What season comes after fall?

Student: The season that comes after fall is winter.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Gibbons (Chapter 2, 2015) introduces two terms that are linked to classroom talk. Dialogic teaching refers to a classroom technique that encourages students to make connections to their prior learning both in and out of school and to voice their thoughts freely, knowing that their ideas and opinions will be accepted by their teachers and peers. Dialogic teaching is a combination of teacher talk, student talk, individual and group contributions. The teacher establishes an environment for conversations that are not dominated or controlled by one person. “Where the talk is teacher-led, exchanges are extended beyond students offering only one-word or short answers, and there is a sustained and topic-related series of exchanges” (Gibbons, 2015, p. 33). From this description, it appears that dialogic teaching reflects the principles of the Communicative Approach to language learning!

Another technique that supports classroom talk is message abundancy. This term refers to strategically delivered, multiple encounters with vocabulary in order to ensure full comprehension. The example offered by Gibbons in Chapter 2 (pp 43-44) of driving to a new location using verbal directions, a map, and a GPS illustrates the effectiveness of multiple encounters with the same message.

Another example of message abundancy is offered here. If the concept of reduce-reuse-recycle is being studied in the mainstream classroom, students can reinforce this concept (which is likely familiar to them in L1) through action items, such as:

- having a wastebasket marked ‘recycle’ in the classroom;

- ‘reusing’ plastic containers for markers, pens, and pencils, and

- ‘reducing’ the amount of waste by asking students to bring refillable water bottles.

Then, as a language arts project, the class can create dual language booklets (using students’ first languages and the language being learned at school) to explain why the reuse-reduce-recycle initiative is important for the environment. For example, if the school language is English, the booklet text in English can be created together in the classroom. Students can then create a translation of the English text together with their parents as a take-home project. Students can illustrate the booklet to complete the project. (To read more about various types of dual language texts, see the article titled Affirming Identity in Multilingual Classrooms.)

To further reinforce the three words in the new language, students can participate in an art project to recreate or redesign the reduce-reuse-recycle symbol using both their L1 and L2.

Left Image: Source: Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Nadine3103. Right Image: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Although some may think that these projects are repetitious, the term reinforcement is more accurate. Repetition means delivering the same message in the same way multiple times, while reinforcement involves different ways of delivering the same message to ensure understanding.

Strategies for dialogic teaching and message abundancy include:

- explicit (direct) vocabulary instruction;

- multiple exposures to words (e.g., oral reading + graphic organizer + text + video clip);

- careful selection of key vocabulary that is useful across many contexts (e.g., describe, investigate, search, illustrate, decide, combine, compare, analyze, demonstrate);

- tasks that involve recurring use of vocabulary;

- active engagement that draws out more than definitions of words;

- use of technology for language reinforcement;

- opportunities for incidental learning.

Strategies to Make Teacher Talk More Comprehensible

There are a few changes that teachers can make in their own teaching practice to facilitate language learning. From your own teaching experience, you may know that language learners have difficulty understanding a string of instructions or an explanation of a concept in class. Students may ask you to repeat what you have said or speak more slowly. Language learners are listening intently for key words or phrases that will help them understand the overall message. However, even when a language teacher (or native speaker) talks at ‘normal speed’, it can sound like a continuous chain of syllables to a language learner. Students need ‘think time’ and ‘wait time’ to process and decipher messages. A few strategies that can make Teacher Talk more comprehensible to language learners are recommended by Reiss (Chapter 6, 2012).

- Slow down speech.

- Limit the use of contractions.

- Use fewer pronouns.

- Simply sentence structure.

- Use familiar words and be consistent.

- Be aware of idioms.

- Audiotape and analyze your own speech.

- Animate your words or be dramatic.

- Use visuals and graphics.

- Display the learning plan.

- Post the homework assignment.

- Review while you teach.

- End each lesson with an oral and written review.

- Provide review notes.

The CEFR/CFR and Speaking

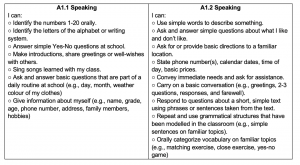

A comparison of the descriptors found in the CEFR/CFR chart (Prokopchuk, 2021), available in Appendix B, will result in a better understanding of how speaking skills progress over time.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

The descriptors in each column illustrate growth with speaking abilities in the new language. For example, a beginner student begins by answering simple yes/no questions (A1.1) but is soon able to carry on a basic conversation (A1.2).

Review Your Learning

- Explain the relationship between listening and comprehension during the language learning process.

- Compare the terms dialogic teaching and message abundancy, and the role each plays in building oral language skills for language learners.

- Identify strategies that improve teacher talk and encourage student talk in the classroom.

Module 5 Glossary

Circumlocution: Talking around a topic using known vocabulary when more specific terms or phrases are unknown or not part of the speaker’s lexicon.

Dialogic teaching: An approach to learning that encourages student contributions, promotes classroom talk, and stimulates students’ thinking through a high level of engagement in the learning process.

Message abundancy: A term coined by Pauline Gibbons to describe multiple encounters with vocabulary in order to ensure full comprehension.

Selective listening: A phrase that describes mental filtering of sounds and messages to focus attention on specific information that is relevant to you.

Stretched language: A process in which a language learner incorporates new or somewhat familiar words into various situations in order to experiment with language and go beyond the comfort zone to build a broader vocabulary base.

References

Cummins, J., Bismilla, V., Chow, P., Cohen, S., Giampapa, F., Leoni, L., Sandhu, P., & Sastri, P. (2005). Affirming Identity in Multilingual Classrooms. In Educational Leadership. 63 (1). pp. 38-43. Retrieved from: https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/affirming-identity-in-multilingual-classrooms

Cohan, A., Honigsfeld, A., & Dove, M. (2020). Team up. Speak up. Fire up! ASCD: Alexandria VA.

Gibbons, P. (2015). Chapter 2: Classroom Talk. In Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning. Teaching English Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom. Second Edition. Heinemann. Portsmouth NH. pp. 23-48.

Gibbons, P. (2015). Chapter 7: Listening – An Active and Thinking Process. In Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning. Teaching English Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom. Second Edition. Heinemann. Portsmouth NH. pp. 182-205

Prokopchuk, N. (2021). The CEFR/CFR Reference Scale: A Practical Tool for Assessing Language Skills in an Additional Language. Chart. College of Education, University of Saskatchewan.

Reiss, J. (2012). Chapter 6: Presenting New Material: Teaching the Lesson. In 120 Content Strategies for English Language Learning. Teaching for Academic Success in Secondary School. Second Edition. Pearson Education Inc. pp.69-85.

Swain, M. (2000). The Output Hypothesis and Beyond: Mediating Acquisition Through Collaborative Dialogue. In Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning, ed. j. Landtolf. Oxford: Oxford University Press.