Introduction

Five approaches and/or methods are presented in this module as a foundational backdrop to current language teaching methodologies. This module answers the question “What approaches or methods used in the past have influenced current language teaching methodologies?

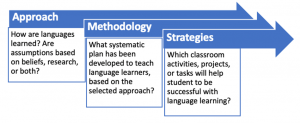

The terms ‘approach’ and ‘method’ are often used synonymously, but a distinction should be made. An approach is a broad term used to describe a set of beliefs or assumptions about the nature of language learning. A method (also called methodology) describes a systematic plan for language teaching that follows a selected approach. Strategies (sometimes called techniques) are actions, tasks, or activities that support a language teaching methodology. Strategies bring a selected methodology to life in the classroom.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan.

Brief video explanations are available here:

- International TEFL & TESOL Training (2017). Theories, Methods, and Techniques of Teaching. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLbVib986kwejHLSDSDglLNPaZtt2uizzc

(1) Grammar Translation Method

This is by far the oldest method of language teaching, dating back several centuries. The original purpose was to translate classic literature from Ancient Latin and Greek into modern languages.

Key Features

In this method, students learn grammatical features of the target language. They are given practice exercises such as grammar drills and sentence translations. The aim is for students to be able to translate with ease between two languages, usually their first or native language (L1) and the target language (L2) being learned. Students begin with basic sentence translations and progress to paragraphs and longer texts. Translation demands high levels of proficiency with written text. Students must understand both the context and meaning in order to translate messages accurately from one language to the other.

Weaknesses

- A major weakness is the intense focus on reading, writing, and grammar without equal attention to oral communication skills. The ability to communicate with others orally is not the focus of this method. Note: Translation should not be confused with interpretation, which is oral.

- Another weakness is the lack of interaction for real-life, authentic communication. The grammar-translation method is static, requiring interaction between the reader and text. Authentic communication is active and engaging, comprised of listening, speaking, reading, and writing for various purposes with different target audiences.

- A third weakness is an overemphasis on grammatical accuracy and the memorization of grammatical rules, making language learning a rules-driven rather than communication-driven academic pursuit.

Try It!

Translate the following English paragraph to another language that you know.

‘Anne of Green Gables’ by Canadian author L. M. Montgomery offers hours of enjoyable reading for pre-teens. This book recounts the life of an 11-year old red-headed orphan girl named Anne Shirley. Anne is adopted by an elderly brother and sister, Matthew and Marilla Cuthbert, who live on a farm called Green Gables. The farm is near the town of Avonlea on Prince Edward Island. Matthew and Marilla had hoped to adopt a boy to help on the farm. Instead, they receive a very curious, outspoken, and imaginative girl. Anne brings many unexpected adventures to Matthew, Marilla, and the residents of Avonlea.

Credit: Nadia Prokopchuk

(2) The Natural Approach

In the mid-20th century, linguists recognized that the grammar-translation method had many shortcomings. Krashen and Terrell (1983) proposed a new methodology stemming from Terrell’s belief in the Natural Approach (1977). The approach described the process of learning a new language as being similar to the acquisition of a first language in childhood. Krashen further explained that language acquisition involves spontaneous, experiential learning, and language input from many sources. Krashen added five hypotheses to Terrell’s theory.

a) Acquisition-learning hypothesis – L2 is acquired in a manner parallel to L1. Acquisition, or absorbing the language naturally, is not the same as learning in a classroom (studying the language and its rules).

b) Natural order hypothesis – The brain retains grammatical rules subconsciously in a natural order. Teachers should expect errors during language acquisition, knowing that rules are being absorbed naturally.

c) Monitor hypothesis – Self-correction, a kind of internal monitor, helps students to gain control of the grammatical features of language over time.

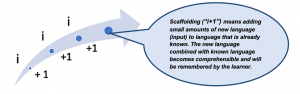

d) Input hypothesis – Students acquire new vocabulary through input that is slightly beyond their current level of language comprehension (“i +1”), guided by mentors or language speakers.

e) Affective filter hypothesis – Pressure, fear, and anxiety have a negative effect on language learning (lowered self-confidence, motivation, worry).

Key Features

The methodology requires that teachers use only the target language, or L2, in the classroom, without references to or support from L1. The goal is to create an atmosphere of immersion, in an effort to simulate language learning in the home environment. No grammatical instruction is provided in the Natural Approach. Students model and repeat language until grammatical patterns are absorbed over time.

As students grow in their ability to communicate using oral language, they are introduced to reading and writing in L2.

The Natural Approach is dependent on comprehensible input, a term introduced by Krashen as part of the Input Hypothesis and symbolized as ‘i + 1’ (information that is known by the learner ‘i’, plus a new piece of information, or ‘1’). Comprehensible input is comparable to scaffolding as described by Vygotsky (1978). In Krashen’s view, language acquisition takes place when known language is blended with small amounts of new language. A language speaker (such as a teacher, guide, or mentor) helps the language learner to add the new language to their existing ‘language storehouse’ in the brain. Vygotsky used the phrase More Knowledgeable Other, or MKO, to describe the person providing guidance.

Krashen further asserted that high levels of comprehensible input build receptive language, which is the language received and stored by the brain through listening & reading. This storehouse of vocabulary is the foundation for productive language, which is the language needed for speaking & writing.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

In 1983, Krashen and Terrell identified four stages of language learning: pre-production (listening, gestures); early production (short phrases); speech emergence (sentences); intermediate fluency (conversation). These stages have influenced approaches to language teaching across North American for several decades.

Weaknesses

- The distinction between acquisition and learning is not firmly supported by research. Terms such as acquiring, learning, and studying language are used interchangeably.

- Assumptions about a natural cognitive order for acquiring grammar are not supported in research. There is little evidence that an immersive approach in the classroom results in learners acquiring grammar naturally and in a logical order.

- The natural immersive environment of the home, where a first language surround infants and young children in the context of daily living, cannot be replicated in an artificial classroom environment.

- The hypothesis builds on a faulty assumption that a new language has no connection to knowledge already available in a first language. This premise discounts conceptual knowledge and literacy skills gained in a student’s first language and stored in the brain.

(3) Audio-Lingual Method

This method aligns well with Krashen’s hypothesis about the need for comprehensible input in language learning. The audio-lingual method promotes the notion that learning language can be simulated inside the classroom by using prescribed dialogues and texts which are comprehensible to the learners. When students are able to repeat dialogues easily, they are asked to transfer (‘transpose’) the memorized language to other situations they may encounter outside the classroom.

The audio-lingual method promotes accuracy over fluency, meaning that vocabulary is limited, but grammatically accurate. The method relies on memorization of set phrases for prescribed contexts or situations. Vocabulary-building does not extend beyond the prescribed dialogues and texts.

Key Features

As with the Natural Approach, the Audio-Lingual Method proposes that students hear and use only the target language in the classroom, with no disruptions from their L1. Students are presented with a series of prepared drills and conversational sequences. They rehearse the sequences in pairs or small groups (e.g., role play, dialogues, class skits) until sentence patterns and grammatical sequences are memorized. In the initial stages, language is presented orally using audio-visual supports (e.g., audio recordings, film/video clips, pictures, props, gestures). Written language is introduced when basic oral skills have been mastered from the prepared dialogues and texts.

Weaknesses

- Language forms are practiced in static drills without explicit instruction to highlight grammatical features of the new language.

- The method limits language learning to well-rehearsed sequences rather than allowing for expanded language learning beyond these sequences.

- Memorized language sequences learned in the classroom are often inadequate for real-life purposes or difficult to transfer to authentic situations encountered outside the classroom.

Try It!

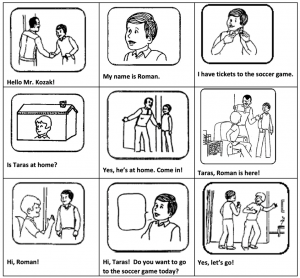

Memorize the text that matches each illustration, then role play with classmates using only the visuals. Three participants are required for the role play: Mr. Kozak, Roman, Taras.

Audio Visual Dialogue – Example for Role-Play (with text)

Source: Ukrainian Canadian Congress (1981). Mova I Rozmova (Language and Conversation). Winnipeg. https://www.spiritsd.ca/ukrainian/eng_high_mova.htm Permission: Courtesy of the Government of Saskatchewan Non-Commercial Reproduction.

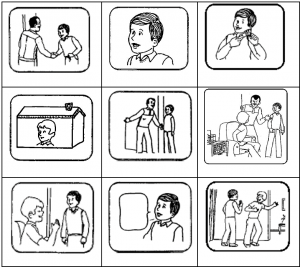

Audio Visual Dialogue – Example for Role-Play (text removed)

Source: Ukrainian Canadian Congress (1981). Mova I Rozmova (Language and Conversation). Winnipeg. https://www.spiritsd.ca/ukrainian/eng_high_mova.htm Permission: Courtesy of the Government of Saskatchewan Non-Commercial Reproduction.

(4) Total Physical Response

Total Physical Response, or TPR, was created by Dr. James Asher (1965). As with the theories of Terrell and Krashen, Asher believed that children learn a new language the way they learn their mother tongue. Children interact with their parents and the environment, combining actions and words for meaningful learning experiences. For example, a parent may say, “Look at me. Give me the toy.” The child will respond physically by looking and then handing the toy to the parent. These listening-responding actions continue for months until the child begins to mimic language by repeating one or two words, followed by phrases, and eventually full sentences.

TPR can be compared to games such as ‘Simon Says’ or ‘Follow the Leader’, in which participants listen for instructions and then perform the actions.

Key Features

The teacher demonstrates a command-action sequence. Students are asked to listen to the command and perform the action several times. Then, together with the teacher, students repeat both the command and the action. After several choral repetitions, the teacher pulls away support (scaffolding) to allow student-led commands and actions.

TPR works particularly well with young children using learning activities such as fingerplays, action stories, and action songs. The combination of language and movement makes learning enjoyable. An extension of TPR with older learners is commonly called ‘role play’. For example, students can act out a cooking lesson, play charades, or participate in a ‘Who Am I’ game. TPR works with large or small classes and requires few props or materials. Teachers need to plan language-movement sequences carefully for best results.

Weaknesses

- Younger children are often very open to movement and actions in the classroom, while older learners may find action sequences uncomfortable or embarrassing (unless the sequences are part of demonstrations, such as cooking or science experiments).

- TPR is highly dependent on brief statements and the use of imperative form of verbs, limiting language learning to commands with action verbs.

- Vocabulary grows at a slow pace, confined to directive statements and commands. Varied sentence patterns, questioning strategies, descriptive language, and interaction sequences for real-world communication are not part of TPR.

Try it!

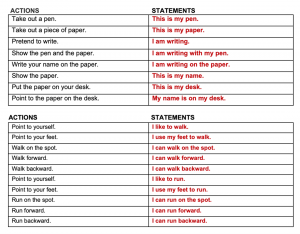

Follow the TPR sequence below.

Step 1: Students perform the actions following the teacher’s example.

Step 2: Students combine the action and statements as a choral exercise led by the teacher.

Step 3: Students repeat the actions and phrases in pairs or small groups on their own.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

(5) The Communicative Approach

This approach grew in popularity in the late 1970s. It blended Krashen’s theory of natural language acquisition with the realization that students learn language more effectively in the classroom when communication is meaningful, purposeful, and applicable to their lives. The Communicative Approach, also known as Communicative Language Teaching, or CLT, does not adhere to one prescribed methodology. Several methodologies have been integrated into CLT, including task-based learning, immersion/partial immersion education, and integrated language and content instruction (ILCI). Other terms for ILCI are content-based instruction (CBI) and content and language integrated learning (CLIL).

Key Features

Three distinguishing features of the Communicative Approach are:

- learner-centered instruction;

- language learning for real-life purposes; and,

- emphasis on fluency over accuracy.

In this approach, the teacher is the guide or facilitator of language learning in the classroom and students are active participants. Students gain confidence in their ability to communicate freely on various topics without feeling pressure to be grammatically accurate. Although grammar is not the central focus of the approach, it is still an important component of classroom instruction. Teachers draw attention to forms and functions of the language in the context of classroom language learning activities. Three methodologies that grew from the Communicative Approach are described below.

Task-Based Learning: This methodology centers on a problem to be solved or a task to be completed using the target language. Students begin with pedagogical tasks that are completed within the classroom, followed by target tasks to be completed outside the classroom. The tasks completed in the classroom allow the students to gain the language skills required to work on tasks outside the classroom, creating a ‘language bridge’ between the classroom and the real world. Tasks are carefully selected and sequenced to build functional language.

Full Immersion/Partial Immersion: Immersion education, in general, reflects the basic principles of communicative language teaching within the context of mainstream K-12 education. Immersion education has several delivery formats, such as partial, early, middle, and late immersion, bilingual education, and dual language education. Lyster and Genesee (2012) describe immersion education as “…a form of bilingual education that provides students with a sheltered classroom environment in which they receive at least half of their subject-matter instruction through the medium of a language that they are learning as a second, foreign, heritage, or indigenous language (L2). In addition, immersion students receive some instruction through the medium of a shared primary language, which normally has majority status in the community. (p.1) The curriculum for immersion education is cumulative in nature, with new language sequenced grade-by-grade into each subject area taught in the target language.

Integrated Language and Content Learning (ILCI). As with immersion, ILCI methodology reflects the belief that language is best learned through active use in authentic contexts. In the case of K-12 education, the context is the school classroom. Students learn to communication in the new language while also learning content in the subject areas. In other words, the classroom is used for learning language and learning content through language. The methodology promotes a combination of language objectives and content area objectives. Teachers create language objectives that target key terms and phrases needed to learn content successfully. The focus on language and content allows students to reach curriculum objectives in the subject areas.

Weaknesses

- As with the Natural Approach, the primary goal of Communicative Language Teaching is fluency rather than accuracy. Attention to grammatical features is left to the discretion of the teacher.

- Programs that are built on topics that reflect student interests may result in weak or unbalanced communication skills.

- Teachers continue to have difficulty recreating real-life communication in the artificial environment of the classroom.

- Assessment of progress can be challenging, given the focus on fluency for authentic purposes. Markers of language success must be clearly defined at the outset.

Try It!

To encourage communication in the target language, create a Word Wall using a strategy called Brainstorming. Ask students to generate words and phrases based on a picture prompt that is relevant to a topic/theme being studied in class.

Step 1: Students share words and phrases that come to mind when looking at the selected picture. The teacher writes everything down on a whiteboard, poster, or flip chart.

Step 2: Ask students to organize the words/phrases into categories. Create lists that can be displayed in the classroom (shown below). Students can refer to the Word Wall when talking, singing, dramatizing, or writing on the topic.

Step 3: Students may transfer vocabulary from the Word Wall to a personal language notebook. Remind students that they may use their L1 as a tool to help them understand and remember the meaning of new vocabulary.

Picture Prompt: Autumn

Source: Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Michael Morse

Students might contribute some/all of the words below. These words can be categorized (e.g., colours, nature, clothing, action words) and used to create a Word Wall.

Word Bank

leaf, leaves, children, boy, girl, fall, fun, many, cool, jacket, sweater, trees, red, yellow, brown, gold, crimson, copper, play, throw, catch, run, jump, laugh, chilly, rustle, falling, autumn, forest, crunch, crackle, crisp, jumping, throwing, catching, rustling, colourful, happy, smiling, playing, laughing, sunshine, chilly, playtime, recess.

Use any format to create the Word Wall. Brief video explanations are available here:

- Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE). The Balanced Literacy Diet. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Q_Ek_ZD7hY

- Hampton, L. (2019). Learning Focused. Ideas for Creating Word Walls. https://learningfocused.com/word-wall-ideas-interactive-classroom-word-wall-makeover/

Review Your Learning

- Describe five language teaching methodologies/approaches that have been used in past decades to promote language study.

- Identify key features and weaknesses of each methodology/approach.

- Recall personal language learning experiences from past years. Which approach or methodology was commonly used by your language teacher(s)?

- Think about your current teaching practices. Which approach or methodology do you frequently use for language instruction? Why?

Module 1 Glossary

Approach: A broad term used to describe a set of beliefs or assumptions about the nature of language learning.

Comprehensible input: A strategy for language learning that involves the use of language that is slightly above the level of language that is understood by learners. Krashen described this small margin between the known and the new as i +1.

Interpretation: Involves oral transfer of information from one language to another, ensuring that the intended meaning is conveyed to the listener.

Method (methodology): Describes a systematic plan for language teaching that reflects a selected approach.

Productive language: The language produced (output) through speaking and writing.

Receptive language: The language received and stored in the brain (input) through listening and reading.

Scaffolding: Process of adding small bits of new information (input) to existing knowledge, guided by an individual who is a ‘More Knowledgeable Other’ (Vygotsky = MKO).

Strategies: Actions, tasks, or activities that support language instruction in the classroom as part of a teaching methodology.

Translation: Involves written transfer of information from one language to another.

References

Brown, H. D. & Lee, H. (2015). Teaching by Principles. An Interactive Approach to Language Pedagogy. Fourth Edition. New York: Pearson Education Inc.

Krashen, S.D. & Terrell, T.D. (1983). The natural approach: Language acquisition in the classroom. London: Prentice Hall Europe.

Lyster, R. & Genesee, F. (2012). Immersion Education. In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315714959_Immersion_Education

McLeod, S. A. (2012). Zone of proximal development. Retrieved from: www.simplypsychology.org/Zone-of-Proximal-Development.html

Richards, J. & Rogers, T. (2014). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Romeo, K. (n/d). Krashen and Terrell’s “Natural Approach”. Retrieved from: https://web.stanford.edu/~hakuta/www/LAU/ICLangLit/NaturalApproach.htm

Terrell, T.D. (1977). A natural approach to the acquisition and learning of a language. Modern Language Journal, 61. 325-336.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Watson, Sue. (2020). How to Brainstorm in the Classroom. ThoughtCo. Retrieved from: thoughtco.com/brainstorm-in-the-classroom-3111340