Chapter 17. Defining Psychological Disorders

17.5 Personality Disorders

Charles Stangor and Jennifer Walinga

Learning Objectives

- Categorize the different types of personality disorders and differentiate antisocial personality disorder from borderline personality disorder.

- Outline the biological and environmental factors that may contribute to a person developing a personality disorder.

To this point in the chapter we have considered the psychological disorders of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) categorization system. A personality disorder is a disorder characterized by inflexible patterns of thinking, feeling, or relating to others that cause problems in personal, social, and work situations. Personality disorders tend to emerge during late childhood or adolescence and usually continue throughout adulthood (Widiger, 2006). The disorders can be problematic for the people who have them, but they are less likely to bring people to a therapist for treatment.

The personality disorders are summarized in Table 17.5, “Descriptions of the Personality Disorders.” They are categorized into three types: those characterized by odd or eccentric behaviour, those characterized by dramatic or erratic behaviour, and those characterized by anxious or inhibited behaviour. As you consider the personality types described in Table 13.5, I’m sure you’ll think of people that you know who have each of these traits, at least to some degree. Probably you know someone who seems a bit suspicious and paranoid, who feels that other people are always “ganging up on him,” and who really do not trust other people very much. Perhaps you know someone who fits the bill of being overly dramatic — the “drama queen” who is always raising a stir and whose emotions seem to turn everything into a big deal. Or you might have a friend who is overly dependent on others and can’t seem to get a life of her own.

The personality traits that make up the personality disorders are common — we see them in the people with whom we interact every day — yet they may become problematic when they are rigid, overused, or interfere with everyday behaviour (Lynam & Widiger, 2001). What is perhaps common to all the disorders is the person’s inability to accurately understand and be sensitive to the motives and needs of the people around them.

| Table 17.5 Descriptions of the Personality Disorders. | ||

| Cluster | Personality disorder | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| A. Odd/eccentric | Schizotypal | Peculiar or eccentric manners of speaking or dressing. Strange beliefs. “Magical thinking” such as belief in ESP or telepathy. Difficulty forming relationships. May react oddly in conversation, not respond, or talk to self. Speech elaborate or difficult to follow. (Possibly a mild form of schizophrenia.) |

| Paranoid | Distrust in others, suspicion that people have sinister motives. Apt to challenge the loyalties of friends and read hostile intentions into others’ actions. Prone to anger and aggressive outbursts but otherwise emotionally cold. Often jealous, guarded, secretive, overly serious. | |

| Schizoid | Extreme introversion and withdrawal from relationships. Prefers to be alone, little interest in others. Humourless, distant, often absorbed with own thoughts and feelings, a daydreamer. Fearful of closeness, with poor social skills, often seen as a “loner.” | |

| B. Dramatic/erratic | Antisocial | Impoverished moral sense or “conscience.” History of deception, crime, legal problems, impulsive and aggressive or violent behaviour. Little emotional empathy or remorse for hurting others. Manipulative, careless, callous. At high risk for substance abuse and alcoholism. |

| Borderline | Unstable moods and intense, stormy personal relationships. Frequent mood changes and anger, unpredictable impulses. Self-mutilation or suicidal threats or gestures to get attention or manipulate others. Self-image fluctuation and a tendency to see others as “all good” or “all bad.” | |

| Histrionic | Constant attention seeking. Grandiose language, provocative dress, exaggerated illnesses, all to gain attention. Believes that everyone loves him. Emotional, lively, overly dramatic, enthusiastic, and excessively flirtatious. | |

| Narcissistic | Inflated sense of self-importance, absorbed by fantasies of self and success. Exaggerates own achievement, assumes others will recognize they are superior. Good first impressions but poor longer-term relationships. Exploitative of others. | |

| C. Anxious/inhibited | Avoidant | Socially anxious and uncomfortable unless he or she is confident of being liked. In contrast with schizoid person, yearns for social contact. Fears criticism and worries about being embarrassed in front of others. Avoids social situations due to fear of rejection. |

| Dependent | Submissive, dependent, requiring excessive approval, reassurance, and advice. Clings to people and fears losing them. Lacking self-confidence. Uncomfortable when alone. May be devastated by end of close relationship or suicidal if breakup is threatened. | |

| Obsessive-compulsive | Conscientious, orderly, perfectionist. Excessive need to do everything “right.” Inflexibly high standards and caution can interfere with his or her productivity. Fear of errors can make this person strict and controlling. Poor expression of emotions. (Not the same as obsessive-compulsive disorder.) | |

| Adapted from American Psychiatric Association, 2013. | ||

The personality disorders create a bit of a problem for diagnosis. For one, it is frequently difficult for the clinician to accurately diagnose which of the many personality disorders a person has, although the friends and colleagues of the person can generally do a good job of it (Oltmanns & Turkheimer, 2006). And the personality disorders are highly comorbid; if a person has one, it’s likely that he or she has others as well. Also, the number of people with personality disorders is estimated to be as high as 15% of the population (Grant et al., 2004), which might make us wonder if these are really disorders in any real sense of the word.

Although they are considered as separate disorders, the personality disorders are essentially milder versions of more severe disorders (Huang et al., 2009). For example, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder is a milder version of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders are characterized by symptoms similar to those of schizophrenia. This overlap in classification causes some confusion, and some theorists have argued that the personality disorders should be eliminated from the DSM. But clinicians normally differentiate Axis I and Axis II disorders, and thus the distinction is useful for them (Krueger, 2005; Phillips, Yen, & Gunderson, 2003; Verheul, 2005).

Although it is not possible to consider the characteristics of each of the personality disorders in this book, let’s focus on two that have important implications for behaviour. The first, borderline personality disorder (BPD), is important because it is so often associated with suicide, and the second, antisocial personality disorder (APD), because it is the foundation of criminal behaviour. Borderline and antisocial personality disorders are also good examples to consider because they are so clearly differentiated in terms of their focus. BPD (more frequently found in women than men) is known as an internalizing disorder because the behaviours that it entails (e.g., suicide and self-mutilation) are mostly directed toward the self. APD (mostly found in men), on the other hand, is a type of externalizing disorder in which the problem behaviours (e.g., lying, fighting, vandalism, and other criminal activity) focus primarily on harm to others.

Borderline Personality Disorder

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a psychological disorder characterized by a prolonged disturbance of personality accompanied by mood swings, unstable personal relationships, identity problems, threats of self-destructive behaviour, fears of abandonment, and impulsivity. BPD is widely diagnosed — up to 20% of psychiatric patients are given the diagnosis, and it may occur in up to 2% of the general population (Hyman, 2002). About three-quarters of diagnosed cases of BDP are women.

People with BPD fear being abandoned by others. They often show a clinging dependency on the other person and engage in manipulation to try to maintain the relationship. They become angry if the other person limits the relationship, but also deny that they care about the person. As a defence against fear of abandonment, borderline people are compulsively social. But their behaviours, including their intense anger, demands, and suspiciousness, repel people.

People with BPD often deal with stress by engaging in self-destructive behaviours, for instance by being sexually promiscuous, getting into fights, binge eating and purging, engaging in self-mutilation or drug abuse, and threatening suicide. These behaviours are designed to call forth a “saving” response from the other person. People with BPD are a continuing burden for police, hospitals, and therapists. Borderline individuals also show disturbance in their concepts of identity: they are uncertain about self-image, gender identity, values, loyalties, and goals. They may have chronic feelings of emptiness or boredom and be unable to tolerate being alone.

BPD has both genetic and environmental roots. In terms of genetics, research has found that those with BPD frequently have neurotransmitter imbalances (Zweig-Frank et al., 2006), and the disorder is heritable (Minzenberg, Poole, & Vinogradov, 2008). In terms of environment, many theories about the causes of BPD focus on a disturbed early relationship between the child and his or her parents. Some theories focus on the development of attachment in early childhood, while others point to parents who fail to provide adequate attention to the child’s feelings. Others focus on parental abuse (both sexual and physical) in adolescence, as well as on divorce, alcoholism, and other stressors (Lobbestael & Arntz, 2009). The dangers of BPD are greater when they are associated with childhood sexual abuse, early age of onset, substance abuse, and aggressive behaviours. The problems are amplified when the diagnosis is comorbid (as it often is) with other disorders, such as substance abuse disorder, major depressive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Skodol et al., 2002).

Research Focus: Affective and Cognitive Deficits in BPD

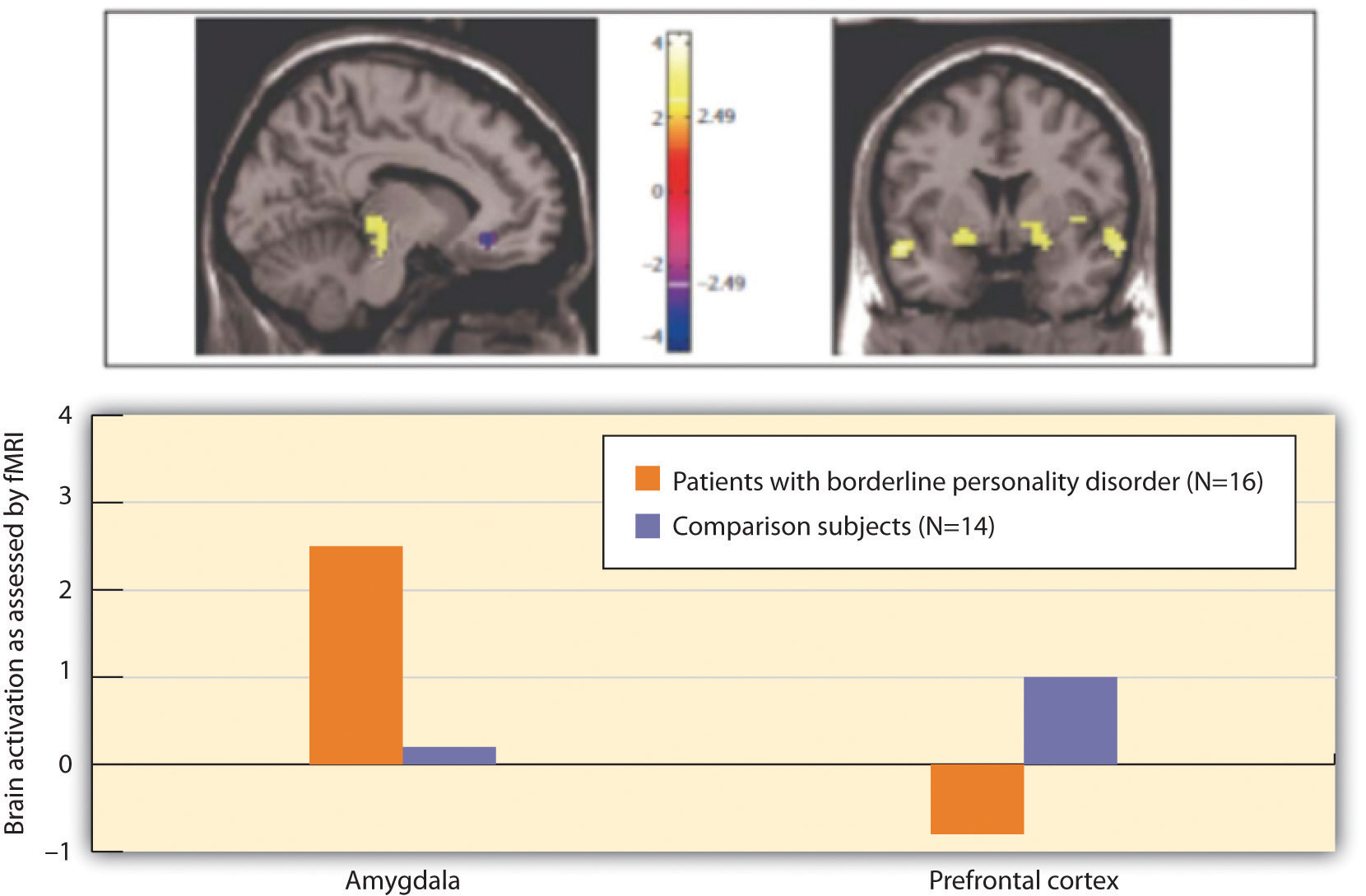

Posner et al. (2003) hypothesized that the difficulty that individuals with BPD have in regulating their lives (e.g., in developing meaningful relationships with other people) may be due to imbalances in the fast and slow emotional pathways in the brain. Specifically, they hypothesized that the fast emotional pathway through the amygdala is too active, and the slow cognitive-emotional pathway through the prefrontal cortex is not active enough in those with BPD.

The participants in their research were 16 patients with BPD and 14 healthy comparison participants. All participants were tested in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine while they performed a task that required them to read emotional and nonemotional words, and then press a button as quickly as possible whenever a word appeared in a normal font and not press the button whenever the word appeared in an italicized font.

The researchers found that while all participants performed the task well, the patients with BPD had more errors than the controls (both in terms of pressing the button when they should not have and not pressing it when they should have). These errors primarily occurred on the negative emotional words.

Figure 17.15 shows the comparison of the level of brain activity in the emotional centres in the amygdala (left panel) and the prefrontal cortex (right panel). In comparison to the controls, the BPD patients showed relatively larger affective responses when they were attempting to quickly respond to the negative emotions, and showed less cognitive activity in the prefrontal cortex in the same conditions. This research suggests that excessive affective reactions and lessened cognitive reactions to emotional stimuli may contribute to the emotional and behavioural volatility of borderline patients.

Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD)

In contrast to borderline personality disorder, which involves primarily feelings of inadequacy and a fear of abandonment, antisocial personality disorder (APD) is characterized by a disregard of the rights of others, and a tendency to violate those rights without being concerned about doing so. APD is a pervasive pattern of violation of the rights of others that begins in childhood or early adolescence and continues into adulthood. APD is about three times more likely to be diagnosed in men than in women. To be diagnosed with APD the person must be 18 years of age or older and have a documented history of conduct disorder before the age of 15. People having antisocial personality disorder are sometimes referred to as “sociopaths” or “psychopaths.”

People with APD feel little distress for the pain they cause others. They lie, engage in violence against animals and people, and frequently have drug and alcohol abuse problems. They are egocentric and frequently impulsive, for instance suddenly changing jobs or relationships. People with APD soon end up with a criminal record and often spend time incarcerated. The intensity of antisocial symptoms tends to peak during the 20s and then may decrease over time.

Biological and environmental factors are both implicated in the development of antisocial personality disorder (Rhee & Waldman, 2002). Twin and adoption studies suggest a genetic predisposition (Rhee & Waldman, 2002), and biological abnormalities include low autonomic activity during stress, biochemical imbalances, right hemisphere abnormalities, and reduced gray matter in the frontal lobes (Lyons-Ruth et al., 2007; Raine, Lencz, Bihrle, LaCasse, & Colletti, 2000). Environmental factors include neglectful and abusive parenting styles, such as the use of harsh and inconsistent discipline and inappropriate modelling (Huesmann & Kirwil, 2007).

Key Takeaways

- A personality disorder is a disorder characterized by inflexible patterns of thinking, feeling, or relating to others that causes problems in personal, social, and work situations.

- Personality disorders are categorized into three clusters, characterized by odd or eccentric behaviour, dramatic or erratic behaviour, and anxious or inhibited behaviour.

- Although they are considered as separate disorders, the personality disorders are essentially milder versions of more severe Axis I disorders.

- Borderline personality disorder is a prolonged disturbance of personality accompanied by mood swings, unstable personal relationships, and identity problems, and it is often associated with suicide.

- Antisocial personality disorder is characterized by a disregard of others’ rights and a tendency to violate those rights without being concerned about doing so.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- What characteristics of men and women do you think make them more likely to have APD and BDP, respectively? Do these differences seem to you to be more genetic or more environmental?

- Do you know people who suffer from antisocial personality disorder? What behaviours do they engage in, and why are these behaviours so harmful to them and others?

Image Attributions

Figure 17.15: Adapted from Posner et al., 2003.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Grant, B., Hasin, D., Stinson, F., Dawson, D., Chou, S., Ruan, W., & Pickering, R. P. (2004). Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(7), 948–958.

Huang, Y., Kotov, R., de Girolamo, G., Preti, A., Angermeyer, M., Benjet, C.,…Kessler, R. C. (2009). DSM-IV personality disorders in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. British Journal of Psychiatry, 195(1), 46–53.

Huesmann, L. R., & Kirwil, L. (2007). Why observing violence increases the risk of violent behavior by the observer. In D. J. Flannery, A. T. Vazsonyi, & I. D. Waldman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of violent behavior and aggression (pp. 545–570). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Hyman, S. E. (2002). A new beginning for research on borderline personality disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 51(12), 933–935.

Krueger, R. F. (2005). Continuity of Axes I and II: Towards a unified model of personality, personality disorders, and clinical disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19, 233–261.

Lobbestael, J., & Arntz, A. (2009). Emotional, cognitive and physiological correlates of abuse-related stress in borderline and antisocial personality disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(2), 116–124.

Lynam, D., & Widiger, T. (2001). Using the five-factor model to represent the DSM-IV personality disorders: An expert consensus approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(3), 401–412.

Lyons-Ruth, K., Holmes, B. M., Sasvari-Szekely, M., Ronai, Z., Nemoda, Z., & Pauls, D. (2007). Serotonin transporter polymorphism and borderline or antisocial traits among low-income young adults. Psychiatric Genetics, 17, 339–343.

Minzenberg, M. J., Poole, J. H., & Vinogradov, S. (2008). A neurocognitive model of borderline personality disorder: Effects of childhood sexual abuse and relationship to adult social attachment disturbance. Development and Psychological disorder. 20(1), 341–368.

Oltmanns, T. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2006). Perceptions of self and others regarding pathological personality traits. In R. F. Krueger & J. L. Tackett (Eds.), Personality and psychopathology (pp. 71–111). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Phillips, K. A., Yen, S., & Gunderson, J. G. (2003). Personality disorders. In R. E. Hales & S. C. Yudofsky (Eds.), Textbook of clinical psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Posner, M., Rothbart, M., Vizueta, N., Thomas, K., Levy, K., Fossella, J.,…Kernberg, O. (2003). An approach to the psychobiology of personality disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 15(4), 1093–1106.

Raine, A., Lencz, T., Bihrle, S., LaCasse, L., & Colletti, P. (2000). Reduced prefrontal gray matter volume and reduced autonomic activity in antisocial personality disorder. Archive of General Psychiatry, 57, 119–127.

Rhee, S. H., & Waldman, I. D. (2002). Genetic and environmental influences on anti-social behavior: A meta-analysis of twin and adoptions studies. Psychological Bulletin, 128(3), 490–529.

Skodol, A. E., Gunderson, J. G., Pfohl, B., Widiger, T. A., Livesley, W. J., & Siever, L. J. (2002). The borderline diagnosis I: Psychopathology, comorbidity, and personality structure. Biological Psychiatry, 51(12), 936–950.

Verheul, R. (2005). Clinical utility for dimensional models of personality pathology. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19, 283–302.

Widiger, T.A. (2006). Understanding personality disorders. In S. K. Huprich (Ed.), Rorschach assessment to the personality disorders. The LEA series in personality and clinical psychology (pp. 3–25). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Zweig-Frank, H., Paris, J., Kin, N. M. N. Y., Schwartz, G., Steiger, H., & Nair, N. P. V. (2006). Childhood sexual abuse in relation to neurobiological challenge tests in patients with borderline personality disorder and normal controls. Psychiatry Research, 141(3), 337–341.