Chapter 12. Stress, Health, and Coping

12.2 Health and Stress

Jennifer Walinga

Learning Objectives

- Understand the nature of stress and its impact on personal, social, economic, and political health.

- Describe the psychological and physiological interactions initiated by stress.

- Identify health symptoms resulting from stress.

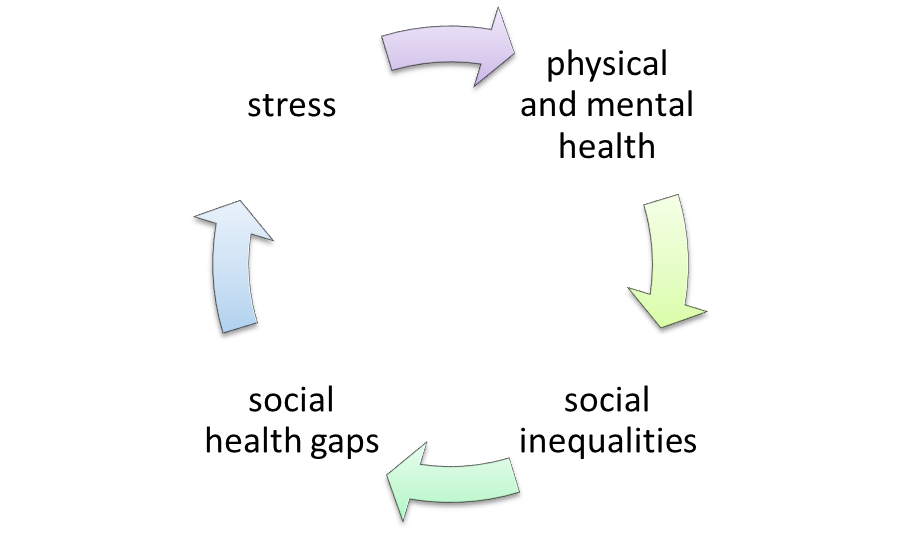

Stress can pose a deleterious effect on health outcomes (Thoits, 2010). In 50 years of research concerning the links between stress and health, several major findings emerge (see Figure 12.4, “The Sociopolitical-Economic Factors of Stress”).

- Personal. When stressors are measured comprehensively, their damaging impacts on physical and mental health are substantial.

- Socioeconomic. Differential exposure to stressful experiences can produce gender, racial-ethnic, marital status, and social class inequalities in physical and mental health.

- Sociopolitical. Stressors proliferate over the life course and across generations, widening health gaps between advantaged and disadvantaged group members.

Coping with stress depends on high levels of mastery, self-esteem, and/or social support that can reduce the impacts of stressors on health and well-being. Therefore, policy recommendations inspired by the snowballing impacts of stress focus on:

- The need for more widely disseminated and employed coping and support interventions and education.

- An increased focus of programs and policies at macro and meso levels of intervention on the structural conditions that put people at risk of stressors.

- The development of programs and policies that target children who are at lifetime risk of ill health and distress due to exposure to poverty and stressful family circumstances.

Negative Impacts of Stress on Health

The human body is designed to react to stress in ways meant to protect against threats from predators and other aggressors. In today’s society, stressors take on a more subtle but equally threatening form such as shouldering a heavy workload, providing for a family, and taking care of children or elderly relatives. The human body treats any perceived stressor as a threat.

When the body encounters a perceived threat (e.g., a near-miss accident, shocking news, a demanding assignment), the hypothalamus, a tiny region at the base of the brain, instigates the “fight-or-flight response” — a combination of nerve and hormonal signals. This system prompts the adrenal glands, located at the top of the kidneys, to release a surge of hormones, including adrenaline and cortisol.

Adrenaline is a hormone that increases heart rate, elevates blood pressure, and boosts energy supplies. Cortisol, the primary stress hormone, increases sugars (glucose) in the bloodstream, enhances the brain’s use of glucose, and increases the availability of substances that repair tissues. Cortisol also curbs functions that would be nonessential or detrimental in a fight-or-flight situation. It alters immune system responses and suppresses the digestive system, the reproductive system, and growth processes. This complex natural alarm system also communicates with regions of the brain that control mood, motivation, and fear.

The body’s stress-response system is usually temporary. Once a perceived threat has passed, hormone levels return to normal. As adrenaline and cortisol levels drop, heart rate and blood pressure return to baseline levels, and other systems resume their regular activities. But when stressors are always present, such as those we experience in a modern, fast-paced society, the body can constantly feel under attack, and the fight-or-flight reaction remains activated.

The long-term activation of the stress-response system — and the subsequent overexposure to cortisol and other stress hormones — can disrupt almost all of the body’s processes and increase the risk of numerous mental and physical health problems, including:

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Digestive problems

- Heart disease

- Sleep problems

- Weight gain

- Memory and concentration impairment

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

Statistics from the Canadian Mental Health Association are alarming in describing the negative health impacts of stress (Higgins, Duxbury, & Lyons, 2008):

- Stress, depression, and burnout are linked to increased absenteeism, and greater use of prescription medications and employee assistance programs.

- Work-related stress costs Canadian taxpayers an estimated $2.8 billion annually in physician visits, hospital stays, and emergency room visits.

- Additionally, 11% of those surveyed say they use drugs as a coping mechanism, with anti-depressant and tranquilizer use on the rise.

- Over half of the respondents reported high levels of perceived stress; one in three reported high levels of burnout and depressed mood.

- Only 41% were satisfied with their lives and one in five was dissatisfied. Almost one in five perceived that their physical health was fair to poor.

- The physical and mental health of Canadian employees has deteriorated over time: 1.5 times more employees reported high depressed mood in 2001 than in 1991. Similarly, 1.4 times more employees reported high levels of perceived stress in 2001 than in 1991.

Positive Impacts of Stress on Health

While research has shown that stress can be extremely deleterious in terms of health outcomes, it can also have positive impacts on health. Because stress is subjective and hinges on perception, the degree to which a person perceives an event as threatening or non-threatening determines the level of stress that person experiences. An individual’s perception or appraisal of an event or instance depends on many factors, such as gender, personality, character, context, memories, upbringing, age, size, relationships, and status – all of which are relative and arbitrary. One individual may perceive a broken-down car on the highway as an extremely stressful event, whereas another individual may perceive such an incident as invigorating, exciting, or a relief.

Eustress

Hans Selye, the prominent stress psychologist, proposed the concept of eustress to capture stress that is not necessarily debilitative and could be potentially facilitative to a person’s sense of well-being, capacity, or performance. Selye explained that every experience or change represents a challenge or stressor to the human system, and thus every experience is met with some degree of “alarm” or arousal (1956). It is individual difference, or “how we take it,” that determines whether a stressor is interpreted as eustress (positive or challenging) or dystress (negative or threatening). Likewise, the multidimensional theory of performance anxiety (Jones & Swain, 1992, 1995; Jones & Hardy, 1993; Martens, Burton, Vealey, Bump, & Smith, 1990) includes a directional component for measuring individuals’ anxiety interpretation along with the traditional intensity component.

Research Focus: Anxiety Direction

In 2007, Hanton and associates studied six high-performance athletes to better understand the role and nature of anxiety and stress as it relates to athletic performance. Specifically, the researchers were interested in understanding athletes’ interpretations of competitive stress and the role that experience plays in that interpretation. Athletes were asked to reflect on the influence of positive and negative critical incidents on the interpretation and appraisal of cognitive and somatic experiences of stress and anxiety symptoms.

Six elite athletes were interviewed prior to critical athletic incidents such as an important race or game, a final game or match, or a particularly challenging event. Some athletes reported negative interpretations of their anxious or nervous feelings:

“I felt anxious thoughts like I had never experienced before. It was the new environment. The fact that we were playing at Wembley with a big crowd. That was unfamiliar and started to overwhelm me. I started to doubt myself and wonder whether I belonged there, whether I had the skills or ability to compete.”

Comparatively, one participant described similar anxious thoughts and feelings but interpreted them positively:

“When I’m nervous and feeling sick inside, that means that the race is important to me and I’m there to achieve something. This time it was almost as though I could be sick, they [symptoms] were that intense. But that was positive because it showed just how important that race was to me and that I was ready to compete.”

The researchers have found a number of reasons for the variation in interpretation of emotional and somatic experiences of anxiety; the factor impacting performance is not the cognitive, emotional, or somatic anxiety itself, but rather the direction or individual’s interpretation of that anxiety that can influence, either facilitatively or debilitatively, performance.

Stress-Related Growth

Stress has also been associated with personal growth and development. Stress can enhance an individual’s resilience or hardiness. The hardiness theoretical model was first presented by Kobasa (1979) and illustrates resilient stress response patterns in individuals and groups. Often regarded as a personality trait or set of traits, psychological hardiness has been described by Bartone (1999) as a style of functioning that includes cognitive, emotional, and behavioural qualities. The hardy style of functioning distinguishes people who stay healthy under stress from those who develop stress-related problems.

Hardiness includes the elements of commitment, control, and challenge. Commitment is the tendency to see the world as interesting and meaningful. Control is the belief in one’s own ability to control or influence events. Challenge involves seeing change and new experiences as exciting opportunities to learn and develop. The hardy person is considered courageous in dealing with new experiences and disappointments, and highly competent. The hardy person is not immune to stress, but is resilient in responding to a variety of stressful conditions. Individuals high in hardiness not only remain healthy, but they also perform better under stress. In this way, hardiness is a chicken-and-egg concept in that hardy people seem to be able to better tolerate and grow from stressful events or become more hardy. It is unclear whether stress fosters hardiness or hardiness is something a person is born with.

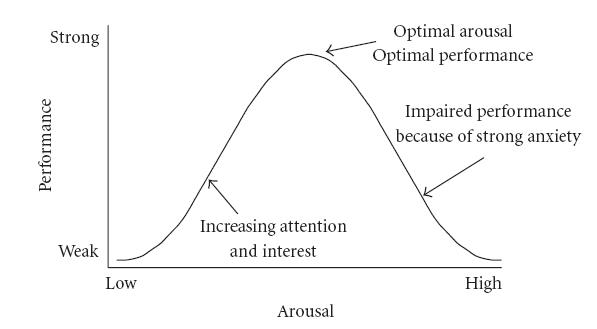

The inverted U hypothesis asserts that, up to a point, stress can be growth inducing but that there is a turning or tipping point when stress just becomes too much and begins to become debilitative (see Figure 12.5, “The Stress Curve”). Feelings of stress (cognitive or physical) can be interpreted negatively to mean that a person is not ready, or positively to mean that a person is ready. It is the person’s interpretation, not the stress itself, that influences the outcome.

Key Takeaways

- When stress is measured comprehensively, it can have debilitating effects on physical and mental health.

- Stress has been shown to create inequalities socioeconomically.

- Over time, stress can lead to health divisions and sociopolitical disparities.

- Policies and programming that enhance education, address structural conditions, and target children are most effective at addressing the negative impacts of stress in society.

- Long-term activation of the physiological stress-response system can disrupt almost all of the body’s processes increasing the risk of numerous mental and physical health problems.

- Stress can also have a positive impact on health.

- Anxiety direction is an individual’s interpretation of the stress experience (thoughts and emotions) that determine the impact of a stressor on a person’s health state or performance.

- The inverted U hypothesis asserts that the degree or intensity of stress can act as a tipping point for an individual’s performance or health. There is a subjective point where the stress shifts from invigorating to overwhelming and debilitating.

- Hardiness represents a trait that enables individuals to tolerate and even grow from stressful experiences due to increased commitment, control, and challenge interpretations.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Reflect on a time in your life when stress seemed to increase your negative health outcomes. Based on what you know about the stress response, what physiological factors may have been at play?

- In a group, share a critical incident you perceived to be stressful but from which you believed you grew as a person. What factors may have helped you to tolerate the stress more effectively?

- In what ways could we better educate people to navigate an increasingly stressful environment?

- In a group, discuss the kinds of social and workplace policies that need to be in place to break the cycle of stress-related health problems.

Image Attributions

Figure 12.4: By J. Walinga.

Figure 12.5: (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:HebbianYerkesDodson.JPG) is in the public domain.

References

Bartone, P. T. (1999). Hardiness protects against war-related stress in army reserve forces. Consulting Psychology Journal, 51, 72–82.

Hanton, S., Cropley, B., Neil, R., Mellalieu, S.D., & Miles, A. (2007). Experience in sport and its relationship with competitive anxiety. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 5(1), 28-53.

Higgins, C., Duxbury, L. & Lyons, S. (2008). Reducing Work Life Conflict: What works, what doesn’t? Health Canada. Retrieved May 2014 from http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ewh-semt/pubs/occup-travail/balancing-equilibre/index-eng.php#ack

Jones, G., & Swain, A. B. J. (1992). Intensity and direction dimensions of competitive state anxiety and relationships with competitiveness. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 74, 467–472.

Jones, G., & Swain, A. B. J. (1995). Predispositions to experience debilitative and facilitative anxiety in non-elite performers. The Sport Psychologist, 9, 202–212

Jones, G., Swain, A. B. J., & Hardy, L. (1993). Intensity and direction dimensions of competitive state anxiety and

relationships with performance. Journal of Sport Sciences, 11, 525–532.

Kobasa, S. C. (1979). Stressful life events, personality, and health: An inquiry into hardiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(1), 1–11.

Martens, R., Burton, D., Vealey, R. S., Bump, L. A., & Smith, D. E. (1990). Development and validation of the

competitive state anxiety inventory-2 (CSAI-2). In R. Martens, R. S. Vealey, & D. Burton (Eds.), Competitive

anxiety in sport (pp. 117–213). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics

Selye, H. (1956). The stress of life. New York, NY, US: McGraw-Hill.

Thoits, P.A. (2010). Strd health: major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(1), suppl S41–S53.

Yerkes R. M. , & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18, 459–482.

Long Descriptions

Figure 12.4 long description: Stress can hurt physical and mental health which can increase social inequalities and social health gaps which can cause more stress.