Chapter 14. Growing and Developing

14.1 Conception and Prenatal Development

Charles Stangor and Jennifer Walinga

Learning Objectives

- Review the stages of prenatal development.

- Explain how the developing embryo and fetus may be harmed by the presence of teratogens and describe what a mother can do to reduce her risk.

Conception occurs when an egg from the mother is fertilized by a sperm from the father. In humans, the conception process begins with ovulation, when an ovum, or egg (the largest cell in the human body), which has been stored in one of the mother’s two ovaries, matures and is released into the fallopian tube. Ovulation occurs about halfway through the woman’s menstrual cycle and is aided by the release of a complex combination of hormones. In addition to helping the egg mature, the hormones also cause the lining of the uterus to grow thicker and more suitable for implantation of a fertilized egg.

If the woman has had sexual intercourse within one or two days of the egg’s maturation, one of the up to 500 million sperm deposited by the man’s ejaculation, which are travelling up the fallopian tube, may fertilize the egg. Although few of the sperm are able to make the long journey, some of the strongest swimmers succeed in meeting the egg. As the sperm reach the egg in the fallopian tube, they release enzymes that attack the outer jellylike protective coating of the egg, each trying to be the first to enter. As soon as one of the millions of sperm enters the egg’s coating, the egg immediately responds by both blocking out all other challengers and at the same time pulling in the single successful sperm.

The Zygote

Within several hours of conception, half of the 23 chromosomes from the egg and half of the 23 chromosomes from the sperm fuse together, creating a zygote — a fertilized ovum. The zygote continues to travel down the fallopian tube to the uterus. Although the uterus is only about four inches away in the woman’s body, the zygote’s journey is nevertheless substantial for a microscopic organism, and fewer than half of zygotes survive beyond this earliest stage of life. If the zygote is still viable when it completes the journey, it will attach itself to the wall of the uterus, but if it is not, it will be flushed out in the woman’s menstrual flow. During this time, the cells in the zygote continue to divide: the original two cells become four, those four become eight, and so on, until there are thousands (and eventually trillions) of cells. Soon the cells begin to differentiate, each taking on a separate function. The earliest differentiation is between the cells on the inside of the zygote, which will begin to form the developing human being, and the cells on the outside, which will form the protective environment that will provide support for the new life throughout the pregnancy.

The Embryo

Once the zygote attaches to the wall of the uterus, it is known as the embryo. During the embryonic phase, which will last for the next six weeks, the major internal and external organs are formed, each beginning at the microscopic level, with only a few cells. The changes in the embryo’s appearance will continue rapidly from this point until birth.

While the inner layer of embryonic cells is busy forming the embryo itself, the outer layer is forming the surrounding protective environment that will help the embryo survive the pregnancy. This environment consists of three major structures: The amniotic sac is the fluid-filled reservoir in which the embryo (soon to be known as a fetus) will live until birth, and which acts as both a cushion against outside pressure and as a temperature regulator. The placenta is an organ that allows the exchange of nutrients between the embryo and the mother, while at the same time filtering out harmful material. The filtering occurs through a thin membrane that separates the mother’s blood from the blood of the fetus, allowing them to share only the material that is able to pass through the filter. Finally, the umbilical cord links the embryo directly to the placenta and transfers all material to the fetus. Thus the placenta and the umbilical cord protect the fetus from many foreign agents in the mother’s system that might otherwise pose a threat.

The Fetus

Beginning in the ninth week after conception, the embryo becomes a fetus. The defining characteristic of the fetal stage is growth. All the major aspects of the growing organism have been formed in the embryonic phase, and now the fetus has approximately six months to go from weighing less than an ounce to weighing an average of six to eight pounds. That’s quite a growth spurt.

The fetus begins to take on many of the characteristics of a human being, including moving (by the third month the fetus is able to curl and open its fingers, form fists, and wiggle its toes), sleeping, as well as early forms of swallowing and breathing. The fetus begins to develop its senses, becoming able to distinguish tastes and respond to sounds. Research has found that the fetus even develops some initial preferences. A newborn prefers the mother’s voice to that of a stranger, the languages heard in the womb over other languages (DeCasper & Fifer, 1980; Moon, Cooper, & Fifer, 1993), and even the kinds of foods that the mother ate during the pregnancy (Mennella, Jagnow, & Beauchamp, 2001). By the end of the third month of pregnancy, the sexual organs are visible.

How the Environment Can Affect the Vulnerable Fetus

Prenatal development is a complicated process and may not always go as planned. About 45% of pregnancies result in a miscarriage, often without the mother ever being aware it has occurred (Moore & Persaud, 1993). Although the amniotic sac and the placenta are designed to protect the embryo, substances that can harm the fetus, known as teratogens, may nevertheless cause problems. Teratogens include general environmental factors, such as air pollution and radiation, but also the cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs that the mother may use. Teratogens do not always harm the fetus, but they are more likely to do so when they occur in larger amounts, for longer time periods, and during the more sensitive phases, as when the fetus is growing most rapidly. The most vulnerable period for many of the fetal organs is very early in the pregnancy — before the mother even knows she is pregnant.

Harmful substances that the mother ingests may harm the child. Cigarette smoking, for example, reduces the blood oxygen for both the mother and child and can cause a fetus to be born severely underweight. Another serious threat is fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), a condition caused by maternal alcohol drinking that can lead to numerous detrimental developmental effects, including limb and facial abnormalities, genital anomalies, and intellectual disability. Each year in Canada, it is estimated that nine babies in every 1,000 are born with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), and it is considered one of the leading causes of intellectual disability in the world today (Health Canada, 2006; Niccols, 1994). Because there is no known safe level of alcohol consumption for a pregnant woman, the Public Health Agency of Canada (2011) states that there is no safe amount or safe time to drink alcohol during pregnancy. Therefore, the best approach for expectant mothers is to avoid alcohol completely. Maternal drug abuse is also of major concern and is considered one of the greatest risk factors facing unborn children.

The environment in which the mother is living also has a major impact on infant development (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Haber & Toro, 2004). Children born into homelessness or poverty are more likely to have mothers who are malnourished, who suffer from domestic violence, stress, and other psychological problems, and who smoke or abuse drugs. And children born into poverty are also more likely to be exposed to teratogens. Poverty’s impact may also amplify other issues, creating substantial problems for healthy child development (Evans & English, 2002; Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007).

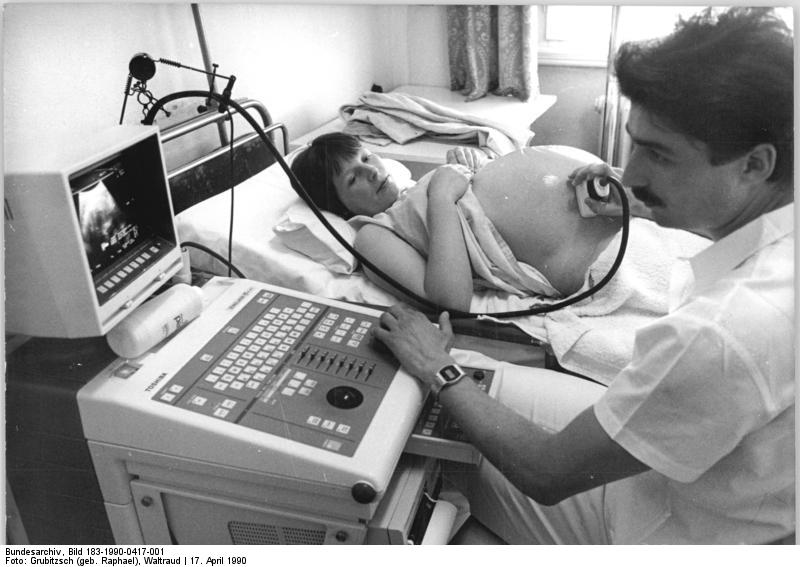

Mothers normally receive genetic and blood tests during the first months of pregnancy to determine the health of the embryo or fetus. They may undergo sonogram, ultrasound, amniocentesis, or other testing (Figure 14.1). The screenings detect potential birth defects, including neural tube defects, chromosomal abnormalities (such as Down syndrome), genetic diseases, and other potentially dangerous conditions. Early diagnosis of prenatal problems can allow medical treatment to improve the health of the fetus.

Key Takeaways

- Development begins at the moment of conception, when the sperm from the father merges with the egg from the mother.

- Within a span of nine months, development progresses from a single cell into a zygote and then into an embryo and fetus.

- The fetus is connected to the mother through the umbilical cord and the placenta, which allow the fetus and mother to exchange nourishment and waste. The fetus is protected by the amniotic sac.

- The embryo and fetus are vulnerable and may be harmed by the presence of teratogens.

- Smoking, alcohol use, and drug use are all likely to be harmful to the developing embryo or fetus, and the mother should entirely refrain from these behaviours during pregnancy or if she expects to become pregnant.

- Environmental factors, especially homelessness and poverty, have a substantial negative effect on healthy child development.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- What behaviours must a woman avoid engaging in when she decides to try to become pregnant, or when she finds out she is pregnant? Do you think the ability of a mother to engage in healthy behaviours should influence her choice to have a child?

- Given the negative effects of poverty on human development, what steps do you think societies should take to try to reduce poverty?

Image Attributions

Figure 14.1: “Leipzig, Universitätsklinik, Untersuchung” by Grubitzsch (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-1990-0417-001,_Leipzig,_Universit%C3%A4tsklinik,_Untersuchung.jpg) is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 DE (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en).

References

DeCasper, A. J., & Fifer, W. P. (1980). Of human bonding: Newborns prefer their mothers’ voices. Science, 208, 1174–1176.

Duncan, G., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). Family poverty, welfare reform, and child development. Child Development, 71(1), 188–196.

Evans, G. W., & English, K. (2002). The environment of poverty: Multiple stressor exposure, psychophysiological stress, and socio-emotional adjustment. Child Development, 73(4), 1238–1248.

Gunnar, M., & Quevedo, K. (2007). The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 145–173.

Haber, M., & Toro, P. (2004). Homelessness among families, children, and adolescents: An ecological-developmental perspective. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 7(3), 123–164.

Health Canada. (2006). It’s your health: Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder [PDF]. Retrieved June 2014 from http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hl-vs/alt_formats/pacrb-dgapcr/pdf/iyh-vsv/diseases-maladies/fasd-etcaf-eng.pdf

Mennella, J. A., Jagnow, C. P., & Beauchamp, G. K. (2001). Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics, 107(6), e88.

Moon, C., Cooper, R. P., & Fifer, W. P. (1993). Two-day-olds prefer their native language. Infant Behavior & Development, 16, 495–500.

Moore, K., & Persaud, T. (1993). The developing human: Clinically oriented embryology (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders.

Niccols, G. A. (1994). Fetal alcohol syndrome: Implications for psychologists. Clinical Psychology Review, 14, 91–111.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2011). The healthy pregnancy guide. Retrieved May 10, 2014 from http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/hp-gs/guide/index-eng.php