2 Module 2: Classical Sociological Perspectives: Origins, Applications and Relevance

Learning Objectives

- Identify the three dimensions of knowledge and outline how they account for the evolution of human knowledge

- Distinguish between the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment

- Explain how social thought differs from sociological thought

- Explain why sociology emerged when it did.

- Describe the central ideas of the founders of sociology (Durkheim, Marx, Weber, Simmel and Martineau)

- Discuss why contemporary sociological thinkers continue to revisit the insights of the classical thinkers

2.0 Locating Sociological Perspectives within a broader Account of the Evolution of Human Knowledge

While sociologists share a common adherence to the framework and central insights of the sociological imagination (as described in Module One), the complexity, historical contingency and multi-layered reality of society–the subject of sociology–has fostered the development of a disciplinary community that is multi-perspectival in its structure, organization and development. To appreciate why this is an important and valuable feature of the discipline of sociology it is instructive to explore recent thinking in the history of science. This is particularly the case in current efforts to systematically account for the historical evolution of human knowledge. As described by Jurgen Renn, it is through conscious reflection on the cognitive, material and social dimensions of knowledge within particular historical contexts that we can gain insight into the complexity of those evolutionary processes.

Building on the general insights of Renn concerning the evolution of human knowledge, a primary objective in this module is to explore the origins of different sociological perspectives from their roots in pre-sociological thought to their emergence within the context of the intellectual, political, economic and social conditions of industrial society.

2.1 Distinguishing Between Social Thought and Sociological Thought

Since ancient times, people have been fascinated by the relationship between individuals and the societies to which they belong. The ancient Greeks might be said to have provided the foundations of sociology through the distinction they drew between physis (nature) and nomos (law or custom). Whereas nature or physis for the Greeks was “what emerges from itself” without human intervention, nomos in the form of laws or customs, were human conventions designed to constrain human behaviour. The modern sociological term “norm” (i.e., a social rule that regulates human behaviour) comes from the Greek term nomos. Histories by Herodotus (484–425 BCE) was a proto-anthropological work that described the great variations in the nomos of different ancient societies around the Mediterranean, indicating that human social life was not a product of nature but a product of human creation. If human social life was the product of an invariable human or biological nature, all cultures would be the same. The concerns of the later Greek philosophers — Socrates (469–399 BCE), Plato (428–347 BCE), and Aristotle (384–322 BCE) — with the ideal form of human community (the polis or city-state) can be derived from the ethical dilemmas of this difference between human nature and human norms. The ideal community might be rational but it was not natural.

In the 13th century, Ma Tuan-Lin, a Chinese historian, first recognized social dynamics as an underlying component of historical development in his seminal encyclopedia, General Study of Literary Remains. The study charted the historical development of Chinese state administration from antiquity in a manner very similar to contemporary institutional analyses. The next century saw the emergence of the historian some consider to be the world’s first sociologist, the Berber scholar Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) of Tunisia. His Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History is known for going beyond descriptive history to an analysis of historical processes of change based on his insights into “the nature of things which are born of civilization” (Khaldun quoted in Becker and Barnes, 1961). Key to his analysis was the distinction between the sedentary life of cities and the nomadic life of pastoral peoples like the Bedouin and Berbers. The nomads, who exist independent of external authority, developed a social bond based on blood lineage and “esprit de corps” (‘Asabijja), which enabled them to mobilize quickly and act in a unified and concerted manner in response to the rugged circumstances of desert life. The sedentaries of the city entered into a different cycle in which esprit de corps is subsumed to institutional power and the intrigues of political factions. The need to be focused on subsistence is replaced by a trend toward increasing luxury, ease, and refinements of taste. The relationship between the two poles of existence, nomadism and sedentary life, was at the basis of the development and decay of civilizations (Becker and Barnes, 1961).

However, it was not until the 19th century that the basis of the modern discipline of sociology can be said to have been truly established. The impetus for the ideas that culminated in sociology can be found in the three major transformations that defined modern society and the culture of modernity: the development of modern science from the 16th century onward, the emergence of democratic forms of government with the American and French Revolutions (1775–1783 and 1789–1799 respectively), and the Industrial Revolution beginning in the 18th century. Not only was the framework for sociological knowledge established in these events, but also the initial motivation for creating a science of society. Early sociologists like Comte and Marx sought to formulate a rational, evidence-based response to the experience of massive social dislocation brought about by the transition from the European feudal era to capitalism. This was a period of unprecedented social problems, from the breakdown of local communities to the hyper-exploitation of industrial labourers. Whether the intention was to restore order to the chaotic disintegration of society, as in Comte’s case, or to provide the basis for a revolutionary transformation in Marx’s, a rational and scientifically comprehensive knowledge of society and its processes was required. It was in this context that “society” itself, in the modern sense of the word, became visible as a phenomenon to early investigators of the social condition.

The development of modern science provided the model of knowledge needed for sociology to move beyond earlier moral, philosophical, and religious types of reflection on the human condition. Key to the development of science was the technological mindset that Max Weber termed the disenchantment of the world: “principally there are no mysterious incalculable forces that come into play, but rather one can, in principle, master all things by calculation” (1919). The focus of knowledge shifted from intuiting the intentions of spirits and gods to systematically observing and testing the world of things through science and technology. Modern science abandoned the medieval view of the world in which God, “the unmoved mover,” defined the natural and social world as a changeless, cyclical creation ordered and given purpose by divine will. Instead modern science combined two philosophical traditions that had historically been at odds: Plato’s rationalism and Aristotle’s empiricism (Berman, 1981). Rationalism sought the laws that governed the truth of reason and ideas, and in the hands of early scientists like Galileo and Newton, found its highest form of expression in the logical formulations of mathematics. Empiricism sought to discover the laws of the operation of the world through the careful, methodical, and detailed observation of the world. The new scientific worldview therefore combined the clear and logically coherent, conceptual formulation of propositions from rationalism, with an empirical method of inquiry based on observation through the senses. Sociology adopted these core principles to emphasize that claims about social life had to be clearly formulated and based on evidence-based procedures. It also gave sociology a technological cast as a type of knowledge which could be used to solve social problems.

The emergence of democratic forms of government in the 18th century demonstrated that humans had the capacity to change the world. The rigid hierarchy of medieval society was not a God-given eternal order, but a human order that could be challenged and improved upon through human intervention. Through the revolutionary process of democratization, society came to be seen as both historical and the product of human endeavours. Age of Enlightenment philosophers like Locke, Voltaire, Montaigne, and Rousseau developed general principles that could be used to explain social life. Their emphasis shifted from the histories and exploits of the aristocracy to the life of ordinary people. Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792) extended the critical analysis of her male Enlightenment contemporaries to the situation of women. Significantly for modern sociology they proposed that the use of reason could be applied to address social ills and to emancipate humanity from servitude. Wollstonecraft for example argued that simply allowing women to have a proper education would enable them to contribute to the improvement of society, especially through their influence on children. On the other hand, the bloody experience of the democratic revolutions, particularly the French Revolution, which resulted in the “Reign of Terror” and ultimately Napoleon’s attempt to subjugate Europe, also provided a cautionary tale for the early sociologists about the need for the sober scientific assessment of society to address social problems.

The Industrial Revolution in a strict sense refers to the development of industrial methods of production, the introduction of industrial machinery, and the organization of labour to serve new manufacturing systems. These economic changes emblemize the massive transformation of human life brought about by the creation of wage labour, capitalist competition, increased mobility, urbanization, individualism, and all the social problems they wrought: poverty, exploitation, dangerous working conditions, crime, filth, disease, and the loss of family and other traditional support networks, etc. It was a time of great social and political upheaval with the rise of empires that exposed many people — for the first time — to societies and cultures other than their own. Millions of people were moving into cities and many people were turning away from their traditional religious beliefs. Wars, strikes, revolts, and revolutionary actions were reactions to underlying social tensions that had never existed before and called for critical examination. August Comte in particular envisioned the new science of sociology as the antidote to conditions that he described as “moral anarchy.”

Sociology therefore emerged; firstly, as an extension of the new worldview of science; secondly, as a part of the Enlightenment project and its focus on historical change, social injustice, and the possibilities of social reform; and thirdly, as a crucial response to the new and unprecedented types of social problems that appeared in the 19th century with the Industrial Revolution. It did not emerge as a unified science, however, as its founders brought distinctly different perspectives to its early formulations.

2.2 Classical Sociological Thought

2.2.1 August Comte: The Father of Sociology

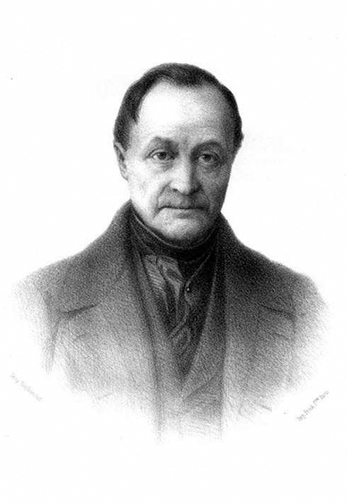

The term sociology was first coined in 1780 by the French essayist Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (1748–1836) in an unpublished manuscript (Fauré et al., 1999). In 1838, the term was reinvented by Auguste Comte (1798–1857). The contradictions of Comte’s life and the times he lived through can be in large part read into the concerns that led to his development of sociology. He was born in 1798, year 6 of the new French Republic, to staunch monarchist and Catholic parents. They lived comfortably off his father’s earnings as a minor bureaucrat in the tax office. Comte originally studied to be an engineer, but after rejecting his parents’ conservative, monarchist views, he declared himself a republican and free spirit at the age of 13 and was eventually kicked out of school at 18 for leading a school riot. This ended his chances of getting a formal education and a position as an academic or government official.

He became a secretary to the utopian socialist philosopher Henri de Saint-Simon (1760–1825) until they had a falling out in 1824 (after St. Simon reputedly purloined some of Comte’s essays and signed his own name to them). Nevertheless, they both thought that society could be studied using the same scientific methods utilized in the natural sciences. Comte also believed in the potential of social scientists to work toward the betterment of society and coined the slogan “order and progress” to reconcile the opposing progressive and conservative factions that had divided the crisis-ridden, post-revolutionary French society. Comte proposed a renewed, organic spiritual order in which the authority of science would be the means to create a rational social order. Through science, each social strata would be reconciled with their place in a hierarchical social order. It is a testament to his influence in the 19th century that the phrase “order and progress” adorns the Brazilian coat of arms (Collins and Makowsky, 1989).

Comte named the scientific study of social patterns positivism. He described his philosophy in a well-attended and popular series of lectures, which he published as The Course in Positive Philosophy (1830–1842) and A General View of Positivism (1848/1977). He believed that using scientific methods to reveal the laws by which societies and individuals interact would usher in a new “positivist” age of history. In principle, positivism, or what Comte called “social physics,” proposed that the study of society could be conducted in the same way that the natural sciences approach the natural world.

While Comte never in fact conducted any social research, his notion of sociology as a positivist science that might effectively socially engineer a better society was deeply influential. Where his influence waned was a result of the way in which he became increasingly obsessive and hostile to all criticism as his ideas progressed beyond positivism as the “science of society” to positivism as the basis of a new cult-like, technocratic “religion of humanity.” The new social order he imagined was deeply conservative and hierarchical, a kind of a caste system with every level of society obliged to reconcile itself with its “scientifically” allotted place. Comte imagined himself at the pinnacle of society, taking the title of “Great Priest of Humanity.” The moral and intellectual anarchy he decried would be resolved through the rule of sociologists who would eliminate the need for unnecessary and divisive democratic dialogue. Social order “must ever be incompatible with a perpetual discussion of the foundations of society” (Comte, 1830/1975).

2.2.2 Theoretical Perspectives on the Formation of Modern Society

While many sociologists have contributed to research on society and social interaction, three thinkers provide the basis of modern-day perspectives. Émile Durkheim, Karl Marx, and Max Weber developed different theoretical approaches to help us understand the development of modern capitalist society. In the following discussion of modern society, we examine Durkheim’s, Marx’s and Weber’s analytical focus on a foundational sociological concept: social structure.

As discussed in Module One, social structures can be defined as general patterns of social behaviour and organization that persist through time. Here Durkheim’s analysis focuses on the impacts of the growing division of labour as a uniquely modern social structure, Marx’s on the economic structures of capitalism (private property, class, competition, crisis, etc.), and Weber’s on the rationalized structures of modern organization. While the aspect of modern structure that Durkheim, Marx and Weber emphasize differs, their common approach is to stress the impact of social structure on culture and ways of life rather than the other way around. This remains a key element of sociological explanation today.

Émile Durkheim: The Pathologies of the Social Order and Functionalism

Émile Durkheim (1858–1917) helped establish sociology as a formal academic discipline by establishing the first European department of sociology at the University of Bordeaux in 1895, and by publishing his Rules of the Sociological Method in 1895. He was born to a Jewish family in the Lorraine province of France (one of the two provinces, along with Alsace, that were lost to the Germans in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871). With the German occupation of Lorraine, the Jewish community suddenly became subject to sporadic anti-Semitic violence, with the Jews often being blamed for the French defeat and the economic/political instability that followed. Durkheim attributed this strange experience of anti-Semitism and scapegoating to the lack of moral purpose in modern society.

As in Comte’s time, France in the late 19th century was the site of major upheavals and sharp political divisions: the loss of the Franco-Prussian War, the Paris Commune (1871) in which 20,000 workers died, the fall and capture of Emperor Napoleon III (Napoleon I’s nephew), the creation of the Third Republic, and the Dreyfus Affair. This undoubtedly led to the focus in Durkheim’s sociology on themes of moral anarchy, decadence, disunity, and disorganization. For Durkheim, sociology was a scientific but also a “moral calling” and one of the central tasks of the sociologist was to determine “the causes of the general temporary maladjustment being undergone by European societies and remedies which may relieve it” (1897/1951). In this respect, Durkheim represented the sociologist as a kind of medical doctor, studying social pathologies of the moral order and proposing social remedies and cures. He saw healthy societies as stable, while pathological societies experienced a breakdown in social norms between individuals and society. He described this breakdown as a state of normlessness or anomie — a lack of norms that give clear direction and purpose to individual actions. As he put it, anomie was the result of “society’s insufficient presence in individuals” (1897/1951).

Key to Durkheim’s approach was the development of a framework for sociology based on the analysis of social facts and social functions. Social facts are those things like law, custom, morality, religious rites, language, money, business practices, etc. that are defined externally to the individual. Social facts:

- Precede the individual and will continue to exist after she or he is gone;

- Consist of details and obligations of which individuals are frequently unaware; and

- Are endowed with an external coercive power by reason of which individuals are controlled.

For Durkheim, social facts were like the facts of the natural sciences. They could be studied without reference to the subjective experience of individuals. He argued that “social facts must be studied as things, that is, as realities external to the individual” (Durkheim, 1895/1964). Individuals experience them as obligations, duties, and restraints on their behaviour, operating independently of their will. They are hardly noticeable when individuals consent to them but provoke reaction when individuals resist.

Durkheim argued that each of these social facts serve one or more functions within a society. They exist to fulfill a societal need. For example, one function of a society’s laws may be to protect society from violence and punish criminal behaviour, while another is to create collective standards of behaviour that people believe in and identify with. Laws create a basis for social solidarity and order. In this manner, each identifiable social fact could be analyzed with regard to its specific function in a society. Like a body in which each organ (heart, liver, brain, etc.) serves a particular function in maintaining the body’s life processes, a healthy society depends on particular functions or needs being met. Durkheim’s insights into society often revealed that social practices, like the worshipping of totem animals in his study of Australian Aboriginal religions, had social functions quite at variance with what practitioners consciously believed they were doing. The honouring of totemic animals through rites and privations functioned to create social solidarity and cohesion for tribes whose lives were otherwise dispersed through the activities of hunting and gathering in a sparse environment.

Émile Durkheim and Functionalism

Émile Durkheim’s (1858-1917) key focus in studying modern society was to understand the conditions under which social and moral cohesion could be reestablished. He observed that European societies of the 19th century had undergone an unprecedented and fractious period of social change that threatened to dissolve society altogether. In his book The Division of Labour in Society (1893/1960), Durkheim argued that as modern societies grew more populated, more complex, and more difficult to regulate, the underlying basis of solidarity or unity within the social order needed to evolve. His primary concern was that the cultural glue that held society together was failing, and that the divisions between people were becoming more conflictual and unmanageable. Therefore Durkheim developed his school of sociology to explain the principles of cohesiveness of societies (i.e., their forms of social solidarity) and how they change and survive over time. He thereby addressed one of the fundamental sociological questions: why do societies hold together rather than fall apart?

Two central components of social solidarity in traditional, premodern societies were the common collective conscience — the communal beliefs, morals, and attitudes of a society shared by all — and high levels of social integration — the strength of ties that people have to their social groups. These societies were held together because most people performed similar tasks and shared values, language, and symbols. There was a low division of labour, a common religious system of social beliefs, and a low degree of individual autonomy. Society was held together on the basis of mechanical solidarity: a minimal division of labour and a shared collective consciousness with harsh punishment for deviation from the norms. Such societies permitted a low degree of individual autonomy. Essentially there was no distinction between the individual conscience and the collective conscience.

Societies with mechanical solidarity act in a mechanical fashion; things are done mostly because they have always been done that way. If anyone violated the collective conscience embodied in laws and taboos, punishment was swift and retributive. This type of thinking was common in preindustrial societies where strong bonds of kinship and a low division of labour created shared morals and values among people, such as among the feudal serfs. When people tend to do the same type of work, Durkheim argued, they tend to think and act alike.

Modern societies, according to Durkheim, were more complex. Collective consciousness was increasingly weak in individuals and the ties of social integration that bound them to others were increasingly few. Modern societies were characterized by an increasing diversity of experience and an increasing division of people into different occupations and specializations. They shared less and less commonalities that could bind them together. However, as Durkheim observed, their ability to carry out their specific functions depended upon others being able to carry out theirs. Modern society was increasingly held together on the basis of a division of labour or organic solidarity: a complex system of interrelated parts, working together to maintain stability, i.e., like an organism (Durkheim, 1893/1960).

According to his theory, as the roles individuals in the division of labour become more specialized and unique, and people increasingly have less in common with one another, they also become increasingly interdependent on one another. Even though there is an increased level of individual autonomy — the development of unique personalities and the opportunity to pursue individualized interests — society has a tendency to cohere because everyone depends on everyone else. The academic relies on the mechanic for the specialized skills required to fix his or her car, the mechanic sends his or her children to university to learn from the academic, and both rely on the baker to provide them with bread for their morning toast. Each member of society relies on the others. In premodern societies, the structures like religious practice that produce shared consciousness and harsh retribution for transgressions function to maintain the solidarity of society as a whole; whereas in modern societies, the occupational structure and its complex division of labour function to maintain solidarity through the creation of mutual interdependence.

While the transition from mechanical to organic solidarity is, in the long run, advantageous for a society, Durkheim noted that it creates periods of chaos and “normlessness.” One of the outcomes of the transition is social anomie. Anomie — literally, “without norms” — is a situation in which society no longer has the support of a firm collective consciousness. There are no clear norms or values to guide and regulate behaviour. Anomie was associated with the rise of industrial society, which removed ties to the land and shared labour; the rise of individualism, which removed limits on what individuals could desire; and the rise of secularism, which removed ritual or symbolic foci and traditional modes of moral regulation. During times of war or rapid economic development, the normative basis of society was also challenged. People isolated in their specialized tasks tend to become alienated from one another and from a sense of collective conscience. However, Durkheim felt that as societies reach an advanced stage of organic solidarity, they avoid anomie by redeveloping a set of shared norms. According to Durkheim, once a society achieves organic solidarity, it has finished its development.

Durkheim and the Sociological Study of Suicide

Durkheim was very influential in defining the subject matter of the new discipline of sociology. For Durkheim, sociology was not about just any phenomena to do with the life of human beings, but only those phenomena which pertained exclusively to a social level of analysis. It was not about the biological or psychological dynamics of human life, for example, but about the external social facts through which the lives of individuals were constrained. Moreover, the dimension of human experience described by social facts had to be explained in its own terms. It could not be explained by biological drives or psychological characteristics of individuals. It was a dimension of reality sui generis (of its own kind, unique in its characteristics). It could not be explained by, or reduced to, its individual components without missing its most important features. As Durkheim put it, “a social fact can only be explained by another social fact” (Durkheim, 1895/1964).

This is the framework of Durkheim’s famous study of suicide. In Suicide: A Study in Sociology (1897/1997), Durkheim attempted to demonstrate the effectiveness of his rules of social research by examining suicide statistics in different police districts. Suicide is perhaps the most personal and most individual of all acts. Its motives would seem to be absolutely unique to the individual and to individual psychopathology. However, what Durkheim observed was that statistical rates of suicide remained fairly constant, year by year and region by region. Moreover, there was no correlation between rates of suicide and rates of psychopathology. Suicide rates did vary, however, according to the social context of the suicides. For example, suicide rates varied according to the religious affiliation of suicides. Protestants had higher rates of suicide than Catholics, even though both religions equally condemn suicide. In some jurisdictions Protestants killed themselves 300% more often than Catholics. Durkheim argued that the key factor that explained the difference in suicide rates (i.e., the statistical rates, not the purely individual motives for the suicides) were the different degrees of social integration of the different religious communities, measured by the degree of authority religious beliefs hold over individuals, and the amount of collective ritual observance and mutual involvement individuals engage in in religious practice. A social fact — suicide rates — was explained by another social fact — degree of social integration.

The key social function of religion was to integrate individuals by linking them to a common external doctrine and to a greater spiritual reality outside of themselves. Religion created moral communities. In this regard, he observed that the degree of authority that religious beliefs held over Catholics was much stronger than for Protestants, who from the time of Luther had been taught to take a critical attitude toward formal doctrine. Protestants were more free to interpret religious belief and in a sense were were more individually responsible for supervising and maintaining their own religious practice. Moreover, in Catholicism the ritual practice of the sacraments, such as confession and taking communion, remained intact, whereas in Protestantism ritual was reduced to a minimum. Participation in the choreographed rituals of religious life created a highly visible, public focus for religious observance, forging a link between private thought and public belief. Because Protestants had to be more individualistic and self-reliant in their religious practice, they were not subject to the strict discipline and external constraints of Catholics. They were less integrated into their communities and more thrown back on their own resources. They were more prone to what Durkheim termed egoistic suicide: suicide which results from the individual ego having to depend on itself for self-regulation (and failing) in the absence of strong social bonds tying it to a community.

Durkheim’s study was unique and insightful because he did not try to explain suicide rates in terms of individual psychopathology. Instead, he regarded the regularity of the suicide rates as a social fact, implying “the existence of collective tendencies exterior to the individual” (Durkheim, 1897/1997), and explained their variation with respect to another social fact: social integration. He wrote, “Suicide varies inversely with the degree of integration of the social groups of which the individual forms a part” (Durkheim, 1897/1997).

Contemporary research into suicide in Canada shows that suicide is the second leading cause of death among young people aged 15 to 34 (behind death by accident) (Navaneelan, 2012). The greatest increase in suicide since the 1960s has been in the age 15-19 age group, increasing by 4.5 times for males and by 3 times for females. In 2009, 23% of deaths among adolescents aged 15-19 were caused by suicide, up from 9% in 1974, (although this difference in percentage is because the rate of suicide remained fairly constant between 1974 and 2009, while death due to accidental causes has declined markedly). On the other hand, married people are the least likely group to commit suicide. Single, never-married people are 3.3 times more likely to commit suicide than married people, followed by widowed and divorced individuals respectively. How do sociologists explain this?

It is clear that adolescence and early adulthood is a period in which social ties to family and society are strained. It is often a confusing period in which teenagers break away from their childhood roles in the family group and establish their independence. Youth unemployment is higher than for other age groups and, since the 1960s, there has been a large increase in divorces and single parent families. These factors tend to decrease the quantity and the intensity of ties to society. Married people on the other hand have both strong affective affinities with their marriage partners and strong social expectations placed on them, especially if they have families: their roles are clear and the norms which guide them are well-defined. According to Durkheim’s proposition, suicide rates vary inversely with the degree of integration of social groups. Adolescents are less integrated into society, which puts them at a higher risk for suicide than married people who are more integrated. It is interesting that the highest rates of suicide in Canada are for adults in midlife, aged 40-59. Midlife is also a time noted for crises of identity, but perhaps more significantly, as Navaneelan (2012) argues, suicide in this age group results from the change in marital status as people try to cope with the transition from married to divorced and widowed.

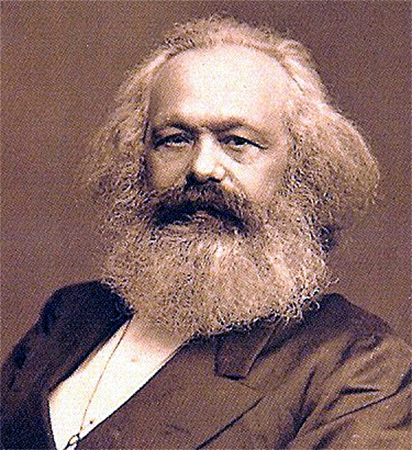

Karl Marx: The Ruthless Critique of Everything Existing

Karl Marx (1818–1883) was a German philosopher and economist. In 1848 he and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) co-authored the Communist Manifesto. This book is one of the most influential political manuscripts in history. It also presents in a highly condensed form Marx’s theory of society, which differed from what Comte proposed. Whereas Comte viewed the goal of sociology as recreating a unified, post-feudal spiritual order that would help to institutionalize a new era of political and social stability, Marx developed a critical analysis of capitalism that saw the material or economic basis of inequality and power relations as the cause of social instability and conflict. The focus of sociology, or what Marx called historical materialism (the “materialist conception of history”), should be the “ruthless critique of everything existing,” as he said in a letter to his friend Arnold Ruge (1802-1880). In this way the goal of sociology would not simply be to scientifically analyze or objectively describe society, but to use a rigorous scientific analysis as a basis to change it. This framework became the foundation of contemporary critical sociology (discussed more fully in Module Three).

Although Marx did not call his analysis “sociology,” his sociological innovation was to provide a social analysis of the economic system. Whereas Adam Smith (1723–1790) and the political economists of the 19th century tried to explain the economic laws of supply and demand solely as a market mechanism (similar to the abstract discussions of stock market indices and investment returns in the business pages of newspapers today), Marx’s analysis showed the social relationships that had created the market system, and the social repercussions of their operation. As such, his analysis of modern society was not static or simply descriptive. He was able to put his finger on the underlying dynamism and continuous change that characterized capitalist society.

Marx was also able to create an effective basis for critical sociology in that what he aimed for in his analysis was, as he put it in another letter to Arnold Ruge, “the self-clarification of the struggles and wishes of the age.” While he took a clear and principled value position in his critique, he did not do so dogmatically, based on an arbitrary moral position of what he personally thought was good and bad. He felt, rather, that a critical social theory must engage in clarifying and supporting the issues of social justice that were inherent within the existing struggles and wishes of the age. In his own work, he endeavoured to show how the variety of specific work actions, strikes, and revolts by workers in different occupations — for better pay, safer working conditions, shorter hours, the right to unionize, etc. — contained the seeds for a vision of universal equality, collective justice, and ultimately the ideal of a classless society.

Karl Marx and Critical Sociology

For Marx, the creation of modern society was tied to the emergence of capitalism as a global economic system. In the mid-19th century, as industrialization was expanding, Karl Marx (1818–1883) observed that the conditions of labour became more and more exploitative. The large manufacturers of steel were particularly ruthless, and their facilities became popularly dubbed “satanic mills” based on a poem by William Blake. Marx’s colleague and friend, Frederick Engels, wrote The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844, which described in detail the horrid conditions.

Photo of Friedrich Engels (right) by George Lester. Marx & Engels is in the public domain.

Add to that the long hours, the use of child labour, and exposure to extreme conditions of heat, cold, and toxic chemicals, and it is no wonder that Marx referred to capital as “dead labour, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks” (Marx, 1867/1995).

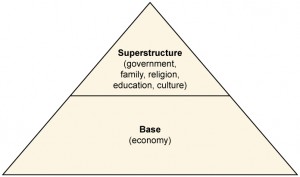

As we saw in Module One, Marx’s explanation of the exploitative nature of industrial society draws on a more comprehensive theory of the development of human societies from the earliest hunter-gatherers to the modern era: historical materialism. For Marx, the underlying structure of societies and of the forces of historical change was predicated on the relationship between the “base and superstructure” of societies. In this model, society’s economic structure forms its base, on which the culture and other social institutions rest, forming its superstructure. For Marx, it is the base—the economic mode of production—that determines what a society’s culture, law, political system, family form, and, most importantly, its typical form of struggle or conflict will be like. Each type of society—hunter-gatherer, pastoral, agrarian, feudal, capitalist—could be characterized as the total way of life that forms around different economic bases.

Marx saw economic conflict in society as the primary means of change. The base of each type of society in history — its economic mode of production — had its own characteristic form of economic struggle. This was because a mode of production is essentially two things: the means of production of a society — anything that is used in production to satisfy needs and maintain existence (e.g., land, animals, tools, machinery, factories, etc.) — and the relations of production of a society — the division of society into economic classes (the social roles allotted to individuals in production). Marx observed historically that in each epoch or type of society since the early “primitive communist” foraging societies, only one class of persons has owned or monopolized the means of production. Different epochs are characterized by different forms of ownership and different class structures: hunter-gatherer (classless/common ownership), agricultural (citizens/slaves), feudal (lords/peasants), and capitalism (capitalists/“free” labourers). As a result, the relations of production have been characterized by relations of domination since the emergence of private property in the early Agrarian societies. Throughout history, societies have been divided into classes with opposed or contradictory interests. These “class antagonisms,” as he called them, periodically lead to periods of social revolution in which it becomes possible for one type of society to replace another.

The most recent revolutionary transformation resulted in the end of feudalism. A new revolutionary class emerged from among the freemen, small property owners, and middle-class burghers of the medieval period to challenge and overthrow the privilege and power of the feudal aristocracy. The members of the bourgeoisie or capitalist class were revolutionary in the sense that they represented a radical change and redistribution of power in European society. Their power was based in the private ownership of industrial property, which they sought to protect through the struggle for property rights, notably in the English Civil War (1642–1651) and the French Revolution (1789–1799). The development of capitalism inaugurated a period of world transformation and incessant change through the destruction of the previous class structure, the ruthless competition for markets, the introduction of new technologies, and the globalization of economic activity.

As Marx and Engels put it in The Communist Manifesto:

The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his “natural superiors”, and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous “cash payment.” It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation…. The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society (1848/1977).

However, the rise of the bourgeoisie and the development of capitalism also brought into existence the class of “free” wage labourers, or the proletariat. The proletariat were made up largely of guild workers and serfs who were freed or expelled from their indentured labour in feudal guild and agricultural production and migrated to the emerging cities where industrial production was centred. They were “free” labour in the sense that they were no longer bound to feudal lords or guildmasters. The new labour relationship was based on a contract. However, as Marx pointed out, this meant in effect that workers could sell their labour as a commodity to whomever they wanted, but if they did not sell their labour they would starve. The capitalist had no obligations to provide them with security, livelihood, or a place to live as the feudal lords had done for their serfs. The source of a new class antagonism developed based on the contradiction of fundamental interests between the bourgeois owners and the wage labourers: where the owners sought to reduce the wages of labourers as far as possible to reduce the costs of production and remain competitive, the workers sought to retain a living wage that could provide for a family and secure living conditions. The outcome, in Marx and Engel’s words, was that “society as a whole is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each other — Bourgeoisie and Proletariat” (1848/1977).

Marx and the Theory of Alienation

For Marx, what we do defines who we are. What it is to be “human” is defined by the capacity we have as a species to creatively transform the world in which we live to meet our needs for survival. Humanity at its core is Homo faber (“Man the Creator”). In historical terms, in spite of the persistent nature of one class dominating another, the element of humanity as creator existed. There was at least some connection between the worker and the product, augmented by the natural conditions of seasons and the rising and setting of the sun, such as we see in an agricultural society. But with the bourgeois revolution and the rise of industry and capitalism, workers now worked for wages alone. The essential elements of creativity and self-affirmation in the free disposition of their labour was replaced by compulsion. The relationship of workers to their efforts was no longer of a human nature, but based purely on animal needs. As Marx put it, the worker “only feels himself freely active in his animal functions of eating, drinking, and procreating, at most also in his dwelling and dress, and feels himself an animal in his human functions” (1932/1977).

Marx described the economic conditions of production under capitalism in terms of alienation. Alienation refers to the condition in which the individual is isolated and divorced from his or her society, work, or the sense of self and common humanity. Marx defined four specific types of alienation that arose with the development of wage labour under capitalism.

Alienation from the product of one’s labour. An industrial worker does not have the opportunity to relate to the product he or she is labouring on. The worker produces commodities, but at the end of the day the commodities not only belong to the capitalist, but serve to enrich the capitalist at the worker’s expense. In Marx’s language, the worker relates to the product of his or her labour “as an alien object that has power over him [or her]” (1932/1977). Workers do not care if they are making watches or cars; they care only that their jobs exist. In the same way, workers may not even know or care what products they are contributing to. A worker on a Ford assembly line may spend all day installing windows on car doors without ever seeing the rest of the car. A cannery worker can spend a lifetime cleaning fish without ever knowing what product they are used for.

Alienation from the process of one’s labour. Workers do not control the conditions of their jobs because they do not own the means of production. If someone is hired to work in a fast food restaurant, that person is expected to make the food exactly the way they are taught. All ingredients must be combined in a particular order and in a particular quantity; there is no room for creativity or change. An employee at Burger King cannot decide to change the spices used on the fries in the same way that an employee on a Ford assembly line cannot decide to place a car’s headlights in a different position. Everything is decided by the owners who then dictate orders to the workers. The workers relate to their own labour as an activity that does not belong to them.

Alienation from others. Workers compete, rather than cooperate. Employees vie for time slots, bonuses, and job security. Different industries and different geographical regions compete for investment. Even when a worker clocks out at night and goes home, the competition does not end. As Marx commented in The Communist Manifesto, “No sooner is the exploitation of the labourer by the manufacturer, so far at an end, that he receives his wages in cash, than he is set upon by the other portion of the bourgeoisie, the landlord, the shopkeeper, the pawnbroker” (1848/1977).

Alienation from one’s humanity. A final outcome of industrialization is a loss of connectivity between a worker and what makes them truly human. Humanity is defined for Marx by “conscious life-activity,” but under conditions of wage labour this is taken not as an end in itself — only a means of satisfying the most base, animal-like needs. The “species being” (i.e., conscious activity) is only confirmed when individuals can create and produce freely, not simply when they work to reproduce their existence and satisfy immediate needs like animals.

Taken as a whole, then, alienation in modern society means that individuals have no control over their lives. There is nothing that ties workers to their occupations. Instead of being able to take pride in an identity such as being a watchmaker, automobile builder, or chef, a person is simply a cog in the machine. Even in feudal societies, people controlled the manner of their labour as to when and how it was carried out. But why, then, does the modern working class not rise up and rebel?

In response to this problem, Marx developed the concept of false consciousness. False consciousness is a condition in which the beliefs, ideals, or ideology of a person are not in the person’s own best interest. In fact, it is the ideology of the dominant class (here, the bourgeoisie capitalists) that is imposed upon the proletariat. Ideas such as the emphasis of competition over cooperation, of hard work being its own reward, of individuals as being the isolated masters of their own fortunes and ruins, etc. clearly benefit the owners of industry. Therefore, to the degree that workers live in a state of false consciousness, they are less likely to question their place in society and assume individual responsibility for existing conditions.

Like other elements of the superstructure, “consciousness,” is a product of the underlying economic; Marx proposed that the workers’ false consciousness would eventually be replaced with class consciousness — the awareness of their actual material and political interests as members of a unified class. In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels wrote,

The weapons with which the bourgeoisie felled feudalism to the ground are now turned against the bourgeoisie itself. But not only has the bourgeoisie forged the weapons that bring death to itself; it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons — the modern working class — the proletarians (1848/1977).

Capitalism developed the industrial means by which the problems of economic scarcity could be resolved and, at the same time, intensified the conditions of exploitation due to competition for markets and profits. Thus emerged the conditions for a successful working class revolution. Instead of existing as an unconscious “class in itself,” the proletariat would become a “class for itself” and act collectively to produce social change (Marx and Engels, 1848/1977). Instead of just being an inert strata of society, the class could become an advocate for social improvements. Only once society entered this state of political consciousness would it be ready for a social revolution. Indeed, Marx predicted that this would be the ultimate outcome and collapse of capitalism.

To summarise, for Marx, the development of capitalism in the 18th and 19th centuries was utterly revolutionary and unprecedented in the scope and scale of the societal transformation it brought about. In his analysis, capitalism is defined by a unique set of features that distinguish it from previous modes of production like feudalism or agrarianism:

- The means of production (i.e., productive property or capital) are privately owned and controlled.

- Capitalists purchase labour power from workers for a wage or salary.

- The goal of production is to profit from selling commodities in a competitive-free market.

- Profit from the sale of commodities is appropriated by the owners of capital. Part of this profit is reinvested as capital in the business enterprise to expand its profitability.

- The competitive accumulation of capital and profit leads to capitalism’s dynamic qualities: constant expansion of markets, globalization of investment, growth and centralization of capital, boom and bust cycles, economic crises, class conflict, etc.

These features are structural, meaning that they are built-into, and reinforced by, the institutional organization of the economy. They are structures, or persistent patterns of social relationship that exist, in a sense, prior to individuals’ personal or voluntary choices and motives. As structures, they can be said to define the rules or internal logic that underlie the surface or observable characteristics of a capitalist society: its political, social, economic, and ideological formations. Some isolated cases may exist where some of these features do not apply, but they define the overall system that has come to govern the contemporary global economy.

Marx’s analysis of the transition from feudalism to capitalism is historical and materialist because it focuses on the changes in the economic mode of production to explain the transformation of the social order. The expansion of the use of money, the development of commodity markets, the introduction of rents, the accumulation and investment of capital, the creation of new technologies of production, and the early stages of the manufactory system, etc. led to the formation of a new class structure (the bourgeoisie and the proletariat), a new political structure (the nation state), and a new ideological structure (science, human rights, individualism, rationalization, the belief in progress, etc.). The unprecedented transformations that created the modern era — urbanization, colonization, population growth, resource exploitation, social and geographical mobility, etc. — originated in the transformation of the mode of production from feudalism to capitalism. “Only the capitalist production of commodities revolutionizes … the entire economic structure of society in a manner eclipsing all previous epochs” (Marx, 1878). In the space of a couple of hundred years, human life on the planet was irremediably and radically altered. As Marx and Engels put it, capitalism had “create[d] a world after its own image” (1848/1977 ).

Max Weber: Verstehende Soziologie

Prominent sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920) established a sociology department in Germany at the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich in 1919. Weber wrote on many topics related to sociology including political change in Russia, the condition of German farm workers, and the history of world religions. He was also a prominent public figure, playing an important role in the German peace delegation in Versailles and in drafting the ill-fated German (Weimar) constitution following the defeat of Germany in World War I.

Weber also made a major contribution to the methodology of sociological research. Along with the philosophers Wilhelm Dilthey (1833–1911) and Heinrich Rickert (1863–1936), Weber believed that it was difficult if not impossible to apply natural science methods to accurately predict the behaviour of groups as positivist sociology hoped to do. They argued that the influence of culture on human behaviour had to be taken into account. What was distinct about human behaviour was that it is essentially meaningful. Human behaviour could not be understood independently of the meanings that individuals attributed to it. A Martian’s analysis of the activities in a skateboard park would be hopelessly confused unless it understood that the skateboarders were motivated by the excitement of taking risks and the pleasure in developing skills. This insight into the meaningful nature of human behaviour even applied to the sociologists themselves, who, they believed, should be aware of how their own cultural biases could influence their research. To deal with this problem, Weber and Dilthey introduced the concept of Verstehen, a German word that means to understand from a subject’s point of view. In seeking Verstehen, outside observers of a social world — an entire culture or a small setting — attempt to understand it empathetically from an insider’s point of view.

In his essay “The Methodological Foundations of Sociology,” Weber described sociology as “a science which attempts the interpretive understanding of social action in order to arrive at a causal explanation of its course and effects” (Weber, 1922). In this way he delimited the field that sociology studies in a manner almost opposite to that of Émile Durkheim. Rather than defining sociology as the study of the unique dimension of external social facts, sociology was concerned with social action: actions to which individuals attach subjective meanings. “Action is social in so far as, by virtue of the subjective meaning attached to it by the acting individual (or individuals), it takes account of the behaviour of others and is thereby oriented in its course” (Weber, 1922). The actions of the young skateboarders can be explained because they hold the experienced boarders in esteem and attempt to emulate their skills, even if it means scraping their bodies on hard concrete from time to time. Weber and other like-minded sociologists founded interpretive sociology whereby social researchers strive to find systematic means to interpret and describe the subjective meanings behind social processes, cultural norms, and societal values. This approach led to research methods like ethnography, participant observation, and phenomenological analysis. Their aim was not to generalize or predict (as in positivistic social science), but to systematically gain an in-depth understanding of social worlds. The natural sciences may be precise, but from the interpretive sociology point of view their methods confine them to study only the external characteristics of things.

Max Weber and Interpretive Sociology

Like the other social thinkers discussed here, Max Weber (1864–1920) was concerned with the important changes taking place in Western society with the advent of capitalism. Arguably, the primary focus of Weber’s entire sociological oeuvre was to determine how and why Western civilization and capitalism developed, and where and when they developed. Why was the West the West? Why did the capitalist system develop in Europe and not elsewhere? Like Marx and Durkheim, he feared that capitalist industrialization would have negative effects on individuals but his analysis differed from theirs in significant respects. Key to the answer to his questions was the concept of rationalization. If other societies had failed to develop modern capitalist enterprise, modern science, and modern, efficient organizational structures, it was because in various ways they had impeded the development of rationalization. Weber’s question was: what are the consequences of rationality for everyday life, for the social order, and for the spiritual fate of humanity?

Unlike Durkheim’s functionalist emphasis on the sources of social solidarity and Marx’s critical emphasis on the materialist basis of class conflict, Weber’s interpretive perspective on modern society emphasizes the development of a rationalized worldview or stance, which he referred to as the disenchantment of the world: “principally there are no mysterious incalculable forces that come into play, but rather one can, in principle, master all things by calculation” (1919/1969). In other words, the processes of rationalization and disenchantment refer principally to the mode in which modern individuals and institutions interpret or analyze the world and the problems that confront them. Rationalization refers to the general tendency in modern society for all institutions and most areas of life to be transformed by the application of rational principles of efficiency and calculation. It overcomes forms of magical thinking and replaces them with cold, objective calculations based on principles of technical efficiency. Older styles of social organization, based on traditional principles of religion, morality, or custom, cannot compete with the efficiency of rational styles of organization and are gradually replaced.

To Weber, capitalism itself became possible through the processes of rationalization. The emergence of capitalism in the West required the prior existence of rational, calculable procedures like double-entry bookkeeping, free labour contracts, free market exchange, and predictable application of law so that it could operate as a form of rational enterprise. Unlike Marx who defined capitalism in terms of the ownership of private property, Weber defined it in terms of its rational processes. For Weber, capitalism is as a form of continuous, calculated economic action in which every element is examined with respect to the logic of investment and return. As opposed to previous types of economic action in which wealth was acquired by force and spent on luxuries, capitalism rested “on the expectation of profit by the utilization of opportunities for exchange, that is, on (formally) peaceful chances for profit.” This implied a continual rationalization of commercial procedures in terms of the logic of capital accumulation. “Where capitalist acquisition is rationally pursued, the corresponding action is adjusted to calculations in terms of capital” (Weber, 1904/1958).

Weber’s analysis of rationalization did not exclusively focus on the conditions for the rise of capitalism however. Capitalism’s “rational” reorganization of economic activity was only one aspect of the broader process of rationalization and disenchantment. Modern science, law, music, art, bureaucracy, politics, and even spiritual life could only have become possible, according to Weber, through the systematic development of precise calculations and planning, technical procedures, and the dominance of “quantitative reckoning.” He felt that other non-Western societies, however highly sophisticated, had impeded these developments by either missing some crucial element of rationality or by holding to non-rational organizational principles or some element of magical thinking. For example, Babylonian astronomy lacked mathematical foundations, Indian geometry lacked rational proofs, Mandarin bureaucracy remained tied to Confucian traditionalism and the Indian caste system lacked the common “brotherhood” necessary for modern citizenship.

Weber argued however that although the process of rationalization leads to efficiency and effective, calculated decision making, it is in the end an irrational system. The emphasis on rationality and efficiency ultimately has negative effects when taken to its conclusion. In modern societies, this is seen when rigid routines and strict adherence to performance-related goals lead to a mechanized work environment and a focus on efficiency for its own sake. To the degree that rational efficiency begins to undermine the substantial human values it was designed to serve (i.e., the ideals of the good life, ethical values, the integrity of human relationships, the enjoyment of beauty and relaxation) rationalization becomes irrational.

An example of the extreme conditions of rationality can be found in Charlie Chaplin’s classic film Modern Times (1936). Chaplin’s character works on an assembly line twisting bolts into place over and over again. The work is paced by the unceasing rotation of the conveyor belt and the technical efficiency of the division of labour. When he has to stop to swat a fly on his nose all the tasks down the line from him are thrown into disarray. He performs his routine task to the point where he cannot stop his jerking motions even after the whistle blows for lunch. Indeed, today we even have a recognized medical condition that results from such tasks, known as “repetitive stress syndrome.”

For Weber, the culmination of industrialization and rationalization results in what he referred to as the iron cage, in which the individual is trapped by the systems of efficiency that were designed to enhance the well-being of humanity. We are trapped in a cage, or literally a “steel housing”(stahlhartes Gehäuse), of efficiently organized processes because rational forms of organization have become indispensable. We must continuously hurry and be efficient because there is no time to “waste.” Weber argued that even if there was a social revolution of the type that Marx envisioned, the bureaucratic and rational organizational structures would remain. There appears to be no alternative. The modern economic order “is now bound to the technical and economic conditions of machine production which today determine the lives of all individuals who are born into this mechanism, not only those directly concerned with economic acquisition, with irresistible force” (Weber, 1904/1958).

Max Weber and the Protestant Work Ethic

If Marx’s analysis is central to the sociological understanding of the structures that emerged with the rise of capitalism, Max Weber is a central figure in the sociological understanding of the effects of capitalism on modern subjectivity: how our basic sense of who we are and what we might aspire to has been defined by the culture and belief system of capitalism. The key work here is Weber’s Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905/1958) in which he lays out the characteristics of the modern ethos of work. Why do we feel compelled to work so hard?

An ethic or ethos refers to a way of life or a way of conducting oneself in life. For Weber, the Protestant work ethic was at the core of the modern ethos. It prescribes a mode of self-conduct in which discipline, work, accumulation of wealth, self-restraint, postponement of enjoyment, and sobriety are the focus of an individual life.

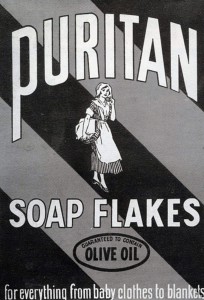

In Weber’s analysis, the ethic was indebted to the religious beliefs and practices of certain Protestant sects like the Lutherans, Calvinists, and Baptists who emerged with the Protestant Reformation (1517–1648). The Protestant theologian Richard Baxter proclaimed that the individual was “called” to their occupation by God, and therefore, they had a duty to “work hard in their calling.” “He who will not work shall not eat” (Baxter, as cited in Weber, 1958). This ethic subsequently worked its way into many of the famous dictums popularized by the American Benjamin Franklin, like “time is money” and “a penny saved is two pence dear” (i.e., “a penny saved is a penny earned”).

In Weber’s estimation, the Protestant ethic was fundamentally important to the emergence of capitalism, and a basic answer to the question of how and why it could emerge. Throughout the period of feudalism and the domination of the Catholic Church, an ethic of poverty and non-materialist values was central to the subjectivity and worldview of the Christian population. From the earliest desert monks and followers of St. Anthony to the great Vatican orders of the Franciscans and Dominicans, the image of Jesus was of a son of God who renounced wealth, possessions, and the material world. “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God” (Mark 10:25). We are of course well aware of the hypocrisy with which these beliefs were often practiced, but even in these cases, wealth was regarded in a different manner prior to the modern era. One worked only as much as was required. As Thomas Aquinas put it “labour [is] only necessary … for the maintenance of individual and community. Where this end is achieved, the precept ceases to have any meaning” (Aquinas, as cited in Weber, 1958). Wealth was not “put to work” in the form of a gradual return on investments as it is under capitalism. How was this medieval belief system reversed? How did capitalism become possible?

The key for Weber was the Protestant sects’ doctrines of predestination, the idea of the personal calling, and the individual’s direct, unmediated relationship to God. In the practice of the Protestant sects, no intermediary or priest interpreted God’s will or granted absolution. God’s will was essentially unknown. The individual could only be recognized as one of the predestined “elect” — one of the saved — through outward signs of grace: through the continuous display of moral self-discipline and, significantly, through the accumulation of earthly rewards that tangibly demonstrated God’s favour. In the absence of any way to know with certainty whether one was destined for salvation, the accumulation of wealth and material success became a sign of spiritual grace rather than a sign of sinful, earthly concerns. For the individual, material success assuaged the existential anxiety concerning the salvation of his or her soul. For the community, material success conferred status.

Weber argues that gradually the practice of working hard in one’s calling lost its religious focus, and the ethic of “sober bourgeois capitalism” (Weber, 1905/1958) became grounded in discipline alone: work and self-improvement for their own sake. This discipline of course produces the rational, predictable, and industrious personality type ideally suited for the capitalist economy. For Weber, the consequence of this, however, is that the modern individual feels compelled to work hard and to live a highly methodical, efficient, and disciplined life to demonstrate their self-worth to themselves as much as anyone. The original goal of all this activity — namely religious salvation — no longer exists. It is a highly rational conduct of life in terms of how one lives, but is simultaneously irrational in terms of why one lives. Weber calls this conundrum of modernity the iron cage. Life in modern society is ordered on the basis of efficiency, rationality, and predictability, and other inefficient or traditional modes of organization are eliminated. Once we are locked into the “technical and economic conditions of machine production” it is difficult to get out or to imagine another way of living, despite the fact that one is renouncing all of the qualities that make life worth living: spending time with friends and family, enjoying the pleasures of sensual and aesthetic life, and/or finding a deeper meaning or purpose of existence. We might be obliged to stay in this iron cage “until the last ton of fossilized coal is burnt” (Weber, 1905/1958).

Georg Simmel: A Sociology of Forms

Georg Simmel (1858–1918) was one of the founding fathers of sociology, although his place in the discipline is not always recognized. In part, this oversight may be explained by the fact that Simmel was a Jewish scholar in Germany at the turn of 20th century and, until 1914, he was unable to attain a proper position as a professor due to anti-Semitism. Despite the brilliance of his sociological insights, the quantity of his publications, and the popularity of his public lectures as Privatdozent at the University of Berlin, his lack of a regular academic position prevented him from having the kind of student following that would create a legacy around his ideas. It might also be explained by some of the unconventional and varied topics that he wrote on: the structure of flirting, the sociology of adventure, the importance of secrecy, the patterns of fashion, the social significance of money, etc. He was generally seen at the time as not having a systematic or integrated theory of society. However, his insights into how social forms emerge at the micro-level of interaction and how they relate to macro-level phenomena remain valuable in contemporary sociology.

Simmel’s sociology focused on the key question, “How is society possible?” His answer led him to develop what he called formal sociology, or the sociology of social forms. In his essay “The Problem of Sociology,” Simmel reaches a strange conclusion for a sociologist: “There is no such thing as society ‘as such.’” “Society” is just the name we give to the “extraordinary multitude and variety of interactions [that] operate at any one moment” (Simmel, 1908/1971). This is a basic insight of micro-sociology. However useful it is to talk about macro-level phenomena like capitalism, the moral order, or rationalization, in the end what these phenomena refer to is a multitude of ongoing, unfinished processes of interaction between specific individuals. Nevertheless, the phenomena of social life do have recognizable forms, and the forms do guide the behaviour of individuals in a regularized way. A bureaucracy is a form of social interaction that persists from day to day. One does not come into work one morning to discover that the rules, job descriptions, paperwork, and hierarchical order of the bureaucracy have disappeared. Simmel’s questions were: How do the forms of social life persist? How did they emerge in the first place? What happens when they get fixed and permanent?

Simmel’s focus on how social forms emerge became very important for micro-sociology, symbolic interactionism, and the studies of hotel lobbies, cigarette girls, and street-corner societies, etc. popularized by the Chicago School in the mid-20th century (Micro-level approaches in sociology are developed more fully in Sociology 112.3). His analysis of the creation of new social forms was particularly tuned in to capturing the fragmentary everyday experience of modern social life that was bound up with the unprecedented nature and scale of the modern city. In his lifetime, the city of Berlin where he lived and taught for most of his career expanded massively after the unification of Germany in the 1870s and, by 1900, became a major European metropolis of 4 million people. The development of a metropolis created a fundamentally new human experience. The inventiveness of people in creating new forms of interaction in response became a rich source of sociological investigation.

Her-story: The History of Gender Inequality

Missing in the classical theoretical accounts of modernity is an explanation of how the developments of modern society, industrialization, and capitalism have affected women differently from men. Despite the differences in Durkheim’s, Marx’s, and Weber’s main themes of analysis, they are equally androcentric to the degree that they cannot account for why women’s experience of modern society is structured differently from men’s, or why the implications of modernity are different for women than they are for men. They tell his-story but neglect her-story.

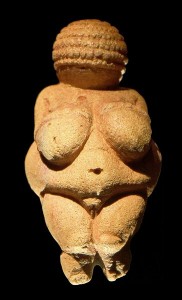

For most of human history, men and women held more or less equal status in society. In hunter-gatherer societies gender inequality was minimal as these societies did not sustain institutionalized power differences. They were based on cooperation, sharing, and mutual support. There was often a gendered division of labour in that men are most frequently the hunters and women the gatherers and child care providers (although this division is not necessarily strict), but as women’s gathering accounted for up to 80% of the food, their economic power in the society was assured. Where headmen lead tribal life, their leadership is informal, based on influence rather than institutional power (Endicott, 1999). In prehistoric Europe from 7000 to 3500 BCE, archaeological evidence indicates that religious life was in fact focused on female deities and fertility, while family kinship was traced through matrilineal (female) descent (Lerner, 1986).

It was not until about 6,000 years ago that gender inequality emerged. With the transition to early agrarian and pastoral types of societies, food surpluses created the conditions for class divisions and power structures to develop. Property and resources passed from collective ownership to family ownership with a corresponding shift in the development of the monogamous, patriarchal (rule by the father) family structure. Women and children also became the property of the patriarch of the family. The invasions of old Europe by the Semites to the south, and the Kurgans to the northeast, led to the imposition of male-dominated hierarchical social structures and the worship of male warrior gods. As agricultural societies developed, so did the practice of slavery. Lerner (1986) argues that the first slaves were women and children.

The development of modern, industrial society has been a two-edged sword in terms of the status of women in society. Marx’s collaborator Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) argued in The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884/1972) that the historical development of the male-dominated monogamous family originated with the development of private property. The family became the means through which property was inherited through the male line. This also led to the separation of a private domestic sphere and a public social sphere. “Household management lost its public character. It no longer concerned society. It became a private service; the wife became the head servant, excluded from all participation in social production” (1884/1972). Under the system of capitalist wage labour, women were doubly exploited. When they worked outside the home as wage labourers they were exploited in the workplace, often as cheaper labour than men. When they worked within the home, they were exploited as the unpaid source of labour needed to reproduce the capitalist workforce. The role of the proletarian housewife was tantamount to “open or concealed domestic slavery” as she had no independent source of income herself (Engels, 1884/1972). Early Canadian law, for example, was based on the idea that the wife’s labour belonged to the husband. This was the case even up to the famous divorce case of Irene Murdoch in 1973, who had worked the family farm in the Turner Valley, Alberta, side by side with her husband for 25 years. When she claimed 50% of the farm assets in the divorce, the judge ruled that the farm belonged to her husband, and she was awarded only $200 a month for a lifetime of work (CBC, 2001).

On the other hand, feminists note that gender inequality was more pronounced and permanent in the feudal and agrarian societies that proceeded capitalism. Women were more or less owned as property, and were kept ignorant and isolated within the domestic sphere. These conditions still exist in the world today. The World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap Report (2014) shows that in a significant number of countries women are severely restricted with respect to economic participation, educational attainment, political empowerment, and basic health outcomes. Yemen, Pakistan, Chad, Syria, and Mali were the five worst countries in the world in terms of women’s inequality.

Yemen is the world’s worst country for women in 2014, according to the WEF. In addition to being one of the worst countries in women’s economic participation and opportunity, Yemen received some of the world’s worst scores in relative educational attainment and political participation for females. Just half of women in the country could read, versus 83% of men. Further, women accounted for just 9% of ministerial positions and for none of the positions in parliament. Child marriage is a huge problem in Yemen. According to Human Rights Watch, as of 2006, 52% of Yemeni girls were married before they reached 18, and 14% were married before they reached 15 years of age (Hess, 2014).

With the rise of capitalism, Engels noted that there was also an improvement in women’s condition when they began to work outside the home. Writers like Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) in her Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792/1997) were also able to see, in the discourses of rights and freedoms of the bourgeois revolutions and the Enlightenment, a general “promise” of universal emancipation that could be extended to include the rights of women. The focus of the Vindication of the Rights of Women was on the right of women to have an education, which would put them on the same footing as men with regard to the knowledge and rationality required for “enlightened” political participation and skilled work outside the home. Whereas property rights, the role of wage labour, and the law of modern society continued to be a source for gender inequality, the principles of universal rights became a powerful resource for women to use in order to press their claims for equality.