6 Module 6: Markets, Organizations and Work

Learning Objectives

- Describe the primary economic systems and their historical development within Agricultural, Industrial, and Postindustrial societies

- Compare and contrast capitalism and socialism both, in theory and in practice

- Describe Neoliberalism as both, ideology and practice

- Discuss how Neoliberalism is related to Embedded Liberalism and Classical Liberalism

- Explain why the monetization of value is strange

- Define technology and describe its evolution

- Describe the evolution and current role of different media, like newspapers, television, and new media

- Distinguish between groups, networks, and organizations

- Describe the characteristics of bureaucracies

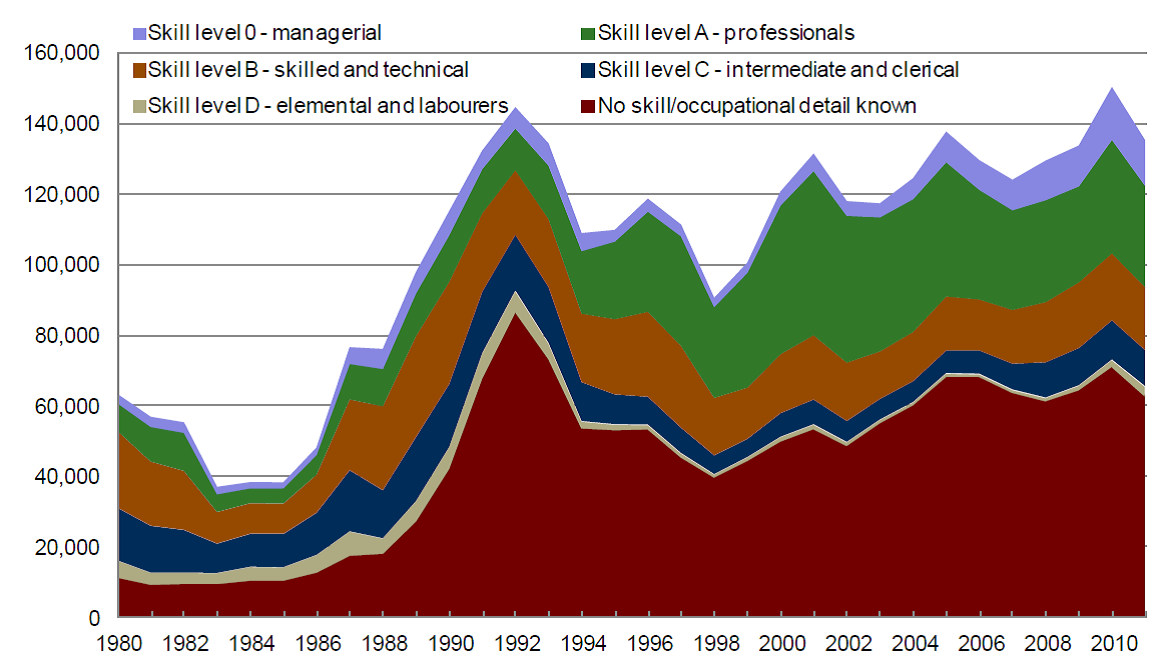

- Describe the current Canadian workforce and the trend of polarization

6.0 Introduction to Markets, Organizations and Work

Ever since the first people traded one item for another, there has been some form of economy in the world. It is how people optimize what they have to meet their wants and needs. Economy refers to the social institutions through which a society’s resources (goods and services) are managed. Goods are the physical objects we find, grow, or make in order to meet our needs and the needs of others. Goods can meet essential needs, such as a place to live, clothing, and food, or they can be luxuries — those things we do not need to live but want anyway. Goods produced for sale on the market are called commodities. In contrast to these objects, services are activities that benefit people. Examples of services include food preparation and delivery, health care, education, and entertainment. These services provide some of the resources that help to maintain and improve a society. The food industry helps ensure that all of a society’s members have access to sustenance. Health care and education systems care for those in need, help foster longevity, and equip people to become productive members of society. Alongside structures of power and governance, the economy is one of human society’s earliest social structures. Our earliest forms of writing (such as Sumerian clay tablets) were developed to record transactions, payments, and debts between merchants. As societies grow and change, so do their economies. The economy of a small farming community is very different from the economy of a large nation with advanced technology. In this module, we will examine different types of economic systems and how they have functioned in various societies. Linked to the examination of economic systems is an examination of the organizational forms in which economic activity is conducted (i.e., governance and administrative) and the implications of these different forms for individuals, as workers, clients, citizens and consumers.

One of the key arguments that sociologists draw from Marx’s analysis is to show that capitalism is not simply an economic system but a social system. The dynamics of capitalism are not a set of obscure economic concerns to be relegated to the business section of the newspaper, but the architecture that underlies the newspaper’s front page headlines; in fact, every headline in the paper. At the time when Marx was developing his analysis, capitalism was still a relatively new economic system, an economic system characterized by private or corporate ownership of goods and the means to produce them. It was also a system that was inherently unstable and prone to crisis, yet increasingly global in its reach. Today capitalism has left no place on earth and no aspect of daily life untouched.

As a social system, one of the main characteristics of capitalism is incessant change, which is why the culture of capitalism is often referred to as modernity. The cultural life of capitalist society can be described as a series of successive “presents,” each of which defines what is modern, new, or fashionable for a brief time before fading away into obscurity like the 78 rpm record, the 8-track tape, and the CD. As Marx and Engels put it, “Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty, and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fast-frozen relations … are swept away, all new ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air…” (1848/1977, p. 224). From the ghost towns that dot the Canadian landscape to the expectation of having a lifetime career, every element of social life under capitalism has a limited duration.

Max Weber’s analysis of modern society centres on the concept of rationalization. Arguably, the primary focus of Weber’s entire sociological oeuvre was to determine how and why Western civilization and capitalism developed where and when they did. Why was the West the West? Why did the Western world modernize and develop modern science, industry, military, and democracy first when, for centuries, Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and the Middle East were technically, scientifically, and culturally more advanced than the West?

Weber argued that the modern forms of society developed in the West because of the process of rationalization: the general tendency of modern institutions and most areas of life to be transformed by the application of instrumental reason — choosing the most efficient means to achieve defined goals — and the overcoming of “magical” thinking — a process that Weber described as the “disenchantment of the world”. In modernity, everything is subject to the cold and rational gaze of the scientist, the technician, the bureaucrat, and the business person. “There are no mysterious incalculable forces that come into play… rather… one can, in principle, master all things by calculation. This means that the world is disenchanted” (Weber, 1919). As the impediments toward rationalization were removed, organizations and institutions were restructured on the principle of maximum efficiency and specialization, while older traditional (inefficient) types of organization were gradually eliminated. Weber’s question was, what are the consequences of rationality for everyday life, for the social order, and for the spiritual fate of humanity?

Through rationalization, all of the institutional structures of modern society are reorganized on the principles of efficiency, calculability, and predictability, which are the bases of the “technical and economic conditions of machine production” that Weber refers to in passages from The Protestant Ethic (1904). As rationalization transforms the institutional and organizational life of modernity, other forms of social organization are eliminated and other purposes of life—spiritual, moral, emotional, traditional, etc.—become irrelevant. Life becomes irrevocably narrower in its focus, and other values are lost. Our attitude towards our own lives becomes oriented to maximizing our own efficiency and eliminating non-productive pursuits and downtime. This is the key to the metaphor of the iron cage by which Weber evokes the new powers of production and organizational effectiveness, the increasingly narrow specialization of tasks and the loss of the Enlightenment ideals of a well-rounded individual and a “full and beautiful humanity.” Having forgotten its spiritual or other purposes of life, humanity succumbed to an order “now bound to the technical and economic conditions of machine production” (Weber, 1904). The modern subject in the iron cage is essentially a narrow specialist or bureaucrat, “only a single cog in an ever-moving mechanism which prescribes to him an essentially fixed route of march” (Weber, 1922).

6.1 Economic Systems

The dominant economic systems of the modern era have been capitalism and socialism, and there have been many variations of each system across the globe. Countries have switched systems as their rulers and economic fortunes have changed. For example, Russia has been transitioning to a market-based economy since the fall of communism in that region of the world. Vietnam, where the economy was devastated by the Vietnam War, restructured to a state-run economy in response, and more recently has been moving toward a socialist-style market economy. In the past, other economic systems reflected the societies that formed them. Many of these earlier systems lasted centuries. These changes in economies raise many questions for sociologists. What are these older economic systems? How did they develop? Why did they fade away? What are the similarities and differences between older economic systems and modern ones?

6.1.1 Economics of Agricultural, Industrial, and Postindustrial Societies

As discussed in Module 2, our earliest ancestors lived as hunter-gatherers. Small groups of extended families roamed from place to place looking for means to subsist. They would settle in an area for a brief time when there were abundant resources. They hunted animals for their meat and gathered wild fruits, vegetables, and cereals. They distributed and ate what they caught or gathered as soon as possible because they had no way of preserving or transporting it. Once the resources of an area ran low, the group had to move on, and everything they owned had to travel with them. Food reserves only consisted of what they could carry. Groups did not typically trade essential goods with other groups due to scarcity. The use of resources was governed by the practice of usufruct, the distribution of resources according to need. Bookchin (1982) notes that in hunter-gatherer societies “property of any kind, communal or otherwise, has yet to acquire independence from the claims of satisfaction” (p. 50).

The Agricultural Revolution

The first true economies arrived when people started raising crops and domesticating animals. Although there is still a great deal of disagreement among archeologists as to the exact timeline, research indicates that agriculture began independently and at different times in several places around the world. The earliest agriculture was in the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East around 11,000–10,000 years ago. Next were the valleys of the Indus, Yangtze, and Yellow Rivers in India and China, between 10,000 and 9,000 years ago. The people living in the highlands of New Guinea developed agriculture between 9,000 and 6,000 years ago, while people were farming in sub-Saharan Africa between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago. Agriculture developed later in the western hemisphere, arising in what would become the eastern United States, central Mexico, and northern South America between 5,000 and 3,000 years ago (Diamond and Bellwood, 2003).

Agriculture began with the simplest of technologies — for example, a pointed stick to break up the soil — but really took off when people harnessed animals to pull an even more efficient tool for the same task: a plow. With this new technology, one family could grow enough crops not only to feed themselves but others as well. Knowing there would be abundant food each year as long as crops were tended led people to abandon the nomadic life of hunter-gatherers and settle down to farm. The improved efficiency in food production meant that not everyone had to toil all day in the fields. As agriculture grew, new jobs emerged, along with new technologies. Excess crops needed to be stored, processed, protected, and transported. Farming equipment and irrigation systems needed to be built and maintained. Wild animals needed to be domesticated and herds shepherded. Economies begin to develop because people now had goods and services to trade. As more people specialized in nonfarming jobs, villages grew into towns and then into cities. Urban areas created the need for administrators and public servants. Disputes over ownership, payments, debts, compensation for damages, and the like led to the need for laws and courts — and the judges, clerks, lawyers, and police who administered and enforced those laws.

At first, most goods and services were traded as gifts or through bartering between small social groups (Mauss, 1922). Exchanging one form of goods or services for another was known as bartering. This system only works when one person happens to have something the other person needs at the same time. To solve this problem, people developed the idea of a means of exchange that could be used at any time: that is, money. Money refers to an object that a society agrees to assign a value to so it can be exchanged for payment. In early economies, money was often objects like cowry shells, rice, barley, or even rum. Precious metals quickly became the preferred means of exchange in many cultures because of their durability and portability. The first coins were minted in Lydia in what is now Turkey around 650–600 BCE (Goldsborough, 2010). Early legal codes established the value of money and the rates of exchange for various commodities. They also established the rules for inheritance, fines as penalties for crimes, and how property was to be divided and taxed (Horne, 1915). A symbolic interactionist would note that bartering and money are systems of symbolic exchange. Monetary objects took on a symbolic meaning, one that carries into our modern-day use of cheques and debit cards.

As city-states grew into countries and countries grew into empires, their economies grew as well. When large empires broke up, their economies broke up too. The governments of newly formed nations sought to protect and increase their markets. They financed voyages of discovery to find new markets and resources all over the world, ushering in a rapid progression of economic development. Colonies were established to secure these markets, and wars were financed to take over territory. These ventures were funded in part by raising capital from investors who were paid back from the goods obtained. Governments and private citizens also set up large trading companies that financed their enterprises around the world by selling stocks and bonds. Governments tried to protect their share of the markets by developing a system called mercantilism. Mercantilism is an economic policy based on accumulating silver and gold by controlling colonial and foreign markets through taxes and other charges. The resulting restrictive practices and exacting demands included monopolies, bans on certain goods, high tariffs, and exclusivity requirements. Mercantilistic governments also promoted manufacturing and, with the ability to fund technological improvements, they helped create the equipment that led to the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution

Up until the end of the 18th century, most manufacturing was done using manual labour. This changed as research led to machines that could be used to manufacture goods. A small number of innovations led to a large number of changes in the British economy. In the textile industries, the spinning of cotton, worsted yarn, and flax could be done more quickly and less expensively using new machines with names like the Spinning Jenny and the Spinning Mule (Bond et al., 2003). Another important innovation was made in the production of iron: coke from coal could now be used in all stages of smelting rather than charcoal from wood, dramatically lowering the cost of iron production while increasing availability (Bond, 2003). James Watt ushered in what many scholars recognize as the greatest change, revolutionizing transportation and, thereby, the entire production of goods with his improved steam engine. As people moved to cities to fill factory jobs, factory production also changed. Workers did their jobs in assembly lines and were trained to complete only one or two steps in the manufacturing process. These advances meant that more finished goods could be manufactured with more efficiency and speed than ever before.

The Industrial Revolution also changed agricultural practices. Until that time, many people practiced subsistence farming in which they produced only enough to feed themselves and pay their taxes. New technology introduced gasoline-powered farm tools such as tractors, seed drills, threshers, and combine harvesters. Farmers were encouraged to plant large fields of a single crop to maximize profits. With improved transportation and the invention of refrigeration, produce could be shipped safely all over the world. The Industrial Revolution modernized the world. With growing resources came growing societies and economies. Between 1800 and 2000, the world’s population grew sixfold, while per capita income saw a tenfold jump (Maddison, 2003). While many people’s lives were improving, the Industrial Revolution also birthed many societal problems. There were inequalities in the system. Owners amassed vast fortunes while labourers, including young children, toiled for long hours in unsafe conditions. Workers’ rights, wage protection, and safe work environments are issues that arose during this period and remain concerns today.

Postindustrial Societies and the Information Age

Postindustrial societies, also known as information societies, have evolved in modernized nations. One of the most valuable goods of the modern era is information. Those who have the means to produce, store, and disseminate information are leaders in this type of society. One way scholars understand the development of different types of societies (like agricultural, industrial, and postindustrial) is by examining their economies in terms of four sectors: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. Each has a different focus. The primary sector extracts and produces raw materials (like metals and crops). The secondary sector turns those raw materials into finished goods. The tertiary sector provides services: child care, health care, and money management. Finally, the quaternary sector produces ideas; these include the research that leads to new technologies, the management of information, and a society’s highest levels of education and the arts (Kenessey, 1987).

Modernization theory proposes a model of quasi-natural economic development, from undeveloped economies to advanced, to explain the difference in distribution of these sectors around the globe. In underdeveloped countries, the majority of the people work in the primary sector. As economies develop, more and more people are employed in the secondary sector. In well-developed economies, such as those in Canada, the United States, Japan, and western Europe, the majority of the workforce is employed in service industries. In Canada, for example, more than 75% of the workforce is employed in the tertiary sector (Statistics Canada, 2012). The rapid increase in computer use in all aspects of daily life is a main reason for the transition to an information economy. Fewer people are needed to work in factories because computerized robots now handle many of the tasks. Other manufacturing jobs have been outsourced to less-developed countries as a result of the developing global economy. The growth of the internet has created industries that exist almost entirely online. Within industries, technology continues to change how goods are produced. For instance, the music and film industries used to produce physical products like CDs and DVDs for distribution. Now those goods are increasingly produced digitally and streamed or downloaded at a much lower physical manufacturing cost. Information and the wherewithal to use it creatively become commodities in a postindustrial economy.

6.2 Dominant Economic Systems of the 20th Century

6.2.1 Capitalism

Scholars do not always agree on a single definition of capitalism. For our purposes, we will define capitalism as an economic system characterized by private ownership of property or capital (as opposed to state ownership), sale of commodities on the open market, the purchase of labour for wages, and the impetus to generate profit and thereby accumulate wealth. This is the type of economy in place in Canada today. Under capitalism, people invest capital (money or property invested in a business venture) in a business to produce a product or service that can be sold in a market to consumers. The investors in the company are generally entitled to a share of any profit made on sales after the costs of production and distribution are taken out. These investors often reinvest their profits to improve and expand the business or acquire new ones. To illustrate how this works, consider this example. Sarah, Antonio, and Chris each invest $250,000 into a start-up company offering an innovative baby product. When the company nets $1 million in profits its first year, a portion of that profit goes back to Sarah, Antonio, and Chris as a return on their investment. Sarah reinvests with the same company to fund the development of a second product line, Antonio uses his return to help another start-up in the technology sector, and Chris buys a small yacht for vacations. The goal for all parties is to maximize profits.

To provide their product or service, owners hire workers, to whom they pay wages. The cost of raw materials, the retail price they charge consumers, and the amount they pay in wages are determined through the law of supply and demand and by competition. This leads to the dynamic qualities of capitalism, including its instability and tendency toward crisis. When demand exceeds supply, prices tend to rise. When supply exceeds demand, prices tend to fall. When multiple businesses market similar products and services to the same buyers, there is competition. Competition can be good for consumers because it can lead to lower prices and higher quality as businesses try to get consumers to buy from them rather than from their competitors. However, competition also leads to key problems like the general tendency for a falling rate of profit, periodic crises of investment, and stock market crashes where billions of dollars of economic value can disappear overnight.

Wages tend to be set in a similar way. People who have talents, skills, education, or training that is in short supply and is needed by businesses tend to earn more than people without comparable skills. Competition in the workforce helps determine how much people will be paid. In times when many people are unemployed and jobs are scarce, people are often willing to accept less than they would when their services are in high demand. In this scenario, businesses are able to maintain or increase profits by obliging workers to accept reduced wages. When fewer people are working or people are working for lower wages, the amount of money circulating in the economy decreases, reducing the demand for commodities and services and creating a vicious cycle of economic recession or depression. To sum up, capitalism is defined by a unique set of features that distinguish it from previous economic systems such as feudalism or agrarianism, or contemporary systems such as socialism or communism:

- The means of production (i.e., productive property or capital) are privately owned and controlled.

- Labour power is purchased from workers by capitalists for a wage or salary.

- The goal of production is to make a profit from selling commodities in a competitive free market.

- Profit from the sale of commodities is appropriated by the owners of capital. Part of this profit is reinvested as capital in the business enterprise in order to expand its profitability.

- The competitive accumulation of capital and profit leads to capitalism’s dynamic qualities: constant expansion of markets, globalization of investment, growth and centralization of capital, boom and bust cycles, economic crises, class conflict, etc.

Capitalism in Practice

As capitalists began to dominate the economies of many countries during the Industrial Revolution, the rapid growth of businesses and their tremendous profitability gave some owners the capital they needed to create enormous corporations that could monopolize an entire industry. Many companies controlled all aspects of the production cycle for their industry, from the raw materials to the production to the stores in which they were sold. These companies were able to use their wealth to buy out or stifle any competition. In Canada, the predatory tactics used by these large monopolies caused the government to take action. In 1889, the government passed the Act for the Prevention and Suppression of Combinations Formed in the Restraint of Trade (precursor to the contemporary Competition Act of 1985), a law designed to break up monopolies and regulate how key industries — such as transportation, steel production, and oil and gas exploration and refining — could conduct business.

Canada is considered a capitalist country. However, the Canadian government has a great deal of influence on private companies through the laws it passes and the regulations enforced by government agencies. Through taxes, regulations on wages, guidelines to protect worker safety and the environment, plus financial rules for banks and investment firms, the government exerts a certain amount of control over how all companies do business. Provincial and federal governments also own, operate, or control large parts of certain industries, such as the post office, schools, hospitals, highways and railroads, and water, sewer, and power utilities. From the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1880s to the development of the Alberta tar sands in the 1960s and 1970s, the Canadian government has played a substantial interventionist role in investing, providing incentives, and assuming ownership in the economy. Debate over the extent to which the government should be involved in the economy remains an issue of contention today. Neoliberal economists and corporate-funded think tanks like the Fraser Institute criticize such involvements, arguing that they lead to economic inefficiency and distortion in free market processes of supply and demand. Others believe intervention is necessary to protect the rights of workers and the well-being of the general population.

6.2.2 Socialism

Socialism is an economic system in which there is government ownership (often referred to as “state run”) of goods and their production, with an impetus to share work and wealth equally among the members of a society. Under socialism, everything that people produce, including services, is considered a social product. Everyone who contributes to the production of a good or to providing a service is entitled to a share in any benefits that come from its sale or use. To make sure all members of society get their fair share, government must be able to control property, production, and distribution. The focus in socialism is on benefiting society, whereas capitalism seeks to benefit the individual. Socialists claim that a capitalistic economy leads to inequality, with unfair distribution of wealth and individuals who use their power at the expense of society. Socialism strives, ideally, to control the economy to avoid the problems and instabilities inherent in capitalism. Within socialism, there are diverging views on the extent to which the economy should be controlled. The communist systems of the Soviet Union, Cuba, and China under Chairman Mao Tse Tung were organized so that all but the most personal items were public property. Contemporary democratic socialism is based on the socialization or government control of essential services such as health care, education, and utilities (electrical power, telecommunications, and sewage). This is essentially a mixed economy based on a free market system and with substantial portions of the economy under private control. Farms, small shops, and businesses are privately owned, while the state might own large businesses in key sectors like energy extraction and transportation. The central component of democratic socialism, however, is the redistribution of wealth and the universal provision of services like child care, health care, and unemployment insurance through a progressive tax system.

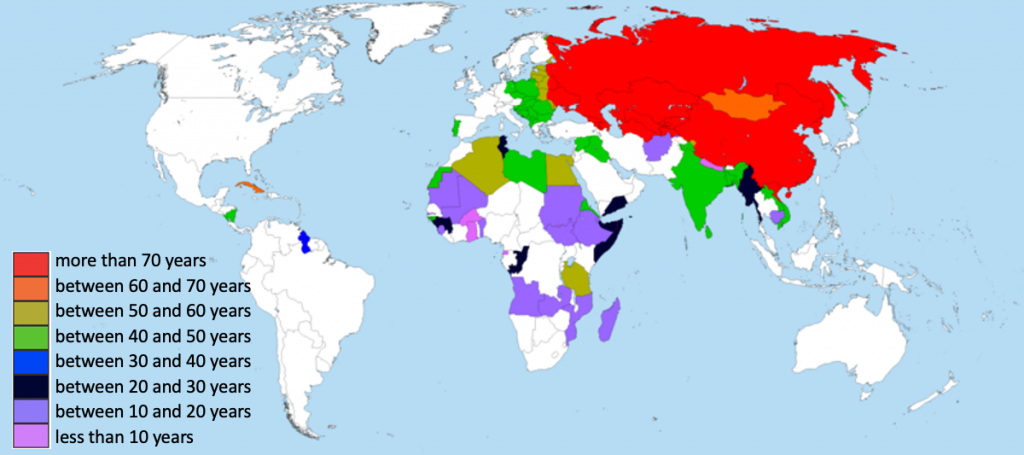

The other area on which socialists disagree is on what level society should exert its control. In communist countries like the former Soviet Union, China, Vietnam, and North Korea, the national government exerts control over the economy centrally. They had the power to tell all businesses what to produce, how much to produce, and what to charge for it. Other socialists believe control should be decentralized so it can be exerted by those most affected by the industries being controlled. An example of this would be a town collectively owning and managing the businesses on which its populace depends. Because of challenges in their economies, several of these communist countries have moved from central planning to letting market forces help determine many production and pricing decisions. Market socialism describes a subtype of socialism that adopts certain traits of capitalism, like allowing limited private ownership or consulting market demands. This could involve situations like profits generated by a company going directly to the employees of the company or being used as public funds (Gregory and Stuart, 2003). Many eastern European and some South American countries have mixed economies. Key industries are nationalized and directly controlled by the government; however, most businesses are privately owned and regulated by the government.

State intervention in the economy has been a central component to the Canadian system since the founding of the country. Democratic socialist movements became prominent in Canadian politics in the 1920s. The efforts of the western agrarian movements, the labour union movement, and the social democratic parties like the CCF (the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation) and its successor, the NDP (New Democratic Party), were instrumental in implementing many of the democratic socialist features of contemporary Canada such as universal health care, old age pensions, employment insurance, and welfare.

Socialism in Practice

As with capitalism, the basic ideas behind socialism go far back in history. Plato, in ancient Greece, suggested a republic in which people shared their material goods. Early Christian communities believed in common ownership, as did the systems of monasteries set up by various religious orders. Many of the leaders of the French Revolution called for the abolition of all private property, not just the estates of the aristocracy they had overthrown. Thomas More’s Utopia, published in 1516, imagined a society with little private property and mandatory labour on a communal farm. Most experimental utopian communities had the abolition of private property as a founding principle. Modern socialism really began as a reaction to the excesses of uncontrolled industrial capitalism in the 1800s and 1900s. The enormous wealth and lavish lifestyles enjoyed by owners contrasted sharply with the miserable conditions of the workers. Some of the first great sociological thinkers studied the rise of socialism. Max Weber admired some aspects of socialism, especially its rationalism and how it could help social reform, but noted that social revolution would not resolve the issues of bureaucratic control and the “iron cage of future bondage” (Greisman and Ritzer, 1981).

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809−1865) was an early anarchist who thought socialism could be used to create utopian communities. In his 1840 book, What Is Property?, he famously stated that “property is theft” (Proudhon, 1840). By this he meant that if an owner did not work to produce or earn the property or profit, then the owner was stealing it from those who did. Proudhon believed economies could work using a principle called mutualism, under which individuals and cooperative groups would exchange products with one another on the basis of mutually satisfactory contracts (Proudhon, 1840).

By far the most important influential thinker on socialism was Karl Marx (Marx and Engels, 1848). Through his own writings and those with his collaborator, industrialist Friedrich Engels, Marx used a materialist analysis to show that throughout history, the resolution of class struggles caused changes in economies. Materialist analyses focus on changes in the economic mode of production to explain the nature and transformation of the social order. Marx saw the history of class conflict developing dialectically from slave and owner, to serf and lord, to journeyman and master, to worker and owner. The resolution of one conflict was precipitated by the emergence of another. In the final epoch of class conflict, Marx argued that the development of capitalism would lead to the creation of a level of technology and economic organization sufficient to meet the needs of everyone in society equally. Scarcity, poverty, and the unequal distribution of resources were the increasingly anachronistic products of the institution of private property. However, capitalism also created the material conditions under which the working class, brought together en masse in factories and other workplaces, would recognize their common interests in ending class exploitation (i.e., they would attain “class consciousness”). Once private property was socialized through the revolution of the working classes, Marx argued that not only would the exploitive relationships of capitalism come to an end, but classes and class conflict themselves would disappear.

Further discussion of the characteristics of capitalism and socialism and an elaboration of the strengths and weaknesses of the respective economic systems is provided by Richard Wolff in the Youtube video, “Economic Update: Capitalism vs Socialism” (April 29, 2019).

6.3 Globalization and the Rise of Neoliberalism

6.3.1 Neoliberalism as Global Economic Policy

As described by Chompsky in the video, ” Neoliberalism is Destroying Democracy” at the end of Module Five, the neoliberal era that emerged in the 1970s produced a shift in government policy from a welfare state model of the redistribution of resources to a neoliberal model of free market distribution of resources. This transition does not take place in a vacuum, however. Just as global capitalism is an economic system characterized by constant change, so too is the relationship between global capitalism and national state policy. Throughout the 19th and first half of the 20th century, the role of the state in the wealthy Northern countries was typically limited to providing the legal mechanisms and enforcement to protect private property. Capitalism itself was for the most part regulated by competition until the stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression of the 1930s. From then on, an awareness grew that the capacity for producing commodities had far exceeded the ability of people to buy them (Harvey, 1989). The economic model of Fordism, adopted in the wealthy Northern countries, offered a solution to the crisis by creating a system of intensive mass production (maximum use of machinery and minute divisions of labour), cheap products, high wages, and mass consumption. This system required a disciplined work force and labour peace, however, which is one reason why states began to take a different role in the economy.

The post-World War II labour-management compromise or “accord” involved the recognition and institutionalization of labour unions, the mediation of the state in capital/labour disputes, the use of taxes and Keynesian economic policy to address economic recessions, and the gradual roll out of social safety net provisions. This set of policies collectively became known as the welfare state. In a high wage/high consumption economy, the ability of individuals to continue to consume even when misfortune struck was paramount, so unemployment insurance, pensions, health care, and disability provisions were important components of the new accord. The accord also reaffirmed the rights of private property or capital to introduce new technology, to reorganize production as they saw fit, and to invest wherever they pleased. Therefore, it was not a system of economic democracy or socialism. Nevertheless, the claims of full employment, continued prosperity, and the creation of a “just society” appeared plausible within the confines of the capitalist economic system.

When Fordism and the welfare state system began to break down in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the relationship between the state and the economy began to change again. In step with the development of the post-Fordist economy of lean production, precarious employment, and niche market consumption, the state began to withdraw from its guarantee of providing universal social services and social security. Neoliberalism is the term used to define the new rationality of government, which abandons the interventionist model of the welfare state to emphasize the use of “free market” mechanisms to regulate society.

Thus, neoliberalism is a set of policies in which the state reduces its role in providing public services, regulating industry, redistributing wealth, and protecting “the commons” — i.e., the collective property that exists for everyone to share (the environment, public and community facilities, airwaves, etc.). These policies are promoted by advocates as ways of addressing the “inefficiency of big government,” the “burden on the taxpayer,” the “need to cut red tape,” and the “culture of entitlement and welfare dependency.” In the place of “big” government, the virtues of the competitive marketplace are extolled. The market is said to promote more efficiency, lower costs, pragmatic decision making, non-favouritism, and a disciplined work ethic, etc.

Of course the facts often tell a different story. For example, government-funded health care in Canada costs far less per person than private health care in the United States (OECD, 2015). A country like Norway, which has a much higher rate of taxation than Canada, also has much lower unemployment, lower income inequality, lower inflation, better public services, a higher standard of living, and yet nevertheless has a globally competitive corporate sector with substantial state ownership and control (especially in the areas of oil and gas production, which is 80% owned by the Norwegian state) (Campbell, 2013). The policies of deregulation that caused the financial crisis of 2008, led even Alan Greenspan (b. 1926) the neoliberal economist and former Chairman of the United States Federal Reserve, to acknowledge that the model of free market “rationality” was flawed (CBC News, 2013). Since the financial crisis was a product of Greenspan’s tenure at the Federal Reserve, and a result of the neoliberal policy of tax cuts and market deregulation that he advocated, his acknowledgment of the failure of free market rationality is significant.

As we noted earlier in this module, while the policies of government within the capitalist state have been changing, they are not occurring in a vacuum; rather, they are unfolding in the context of the developments of global capitalism. From its origins, capitalism has been global in scope. Marx and Engels described globalization in 1848:

The bourgeoisie has through its exploitation of the world market given a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country. To the great chagrin of Reactionists, it has drawn from under the feet of industry the national ground on which it stood. All old-established national industries have been destroyed or are daily being destroyed. They are dislodged by new industries, whose introduction becomes a life and death question for all civilized nations, by industries that no longer work up indigenous raw material, but raw material drawn from the remotest zones; industries whose products are consumed, not only at home, but in every quarter of the globe. In place of the old wants, satisfied by the production of the country, we find new wants, requiring for their satisfaction the products of distant lands and climes. In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal inter-dependence of nations. (Marx & Engels, 1848/1977, p. 224)

The process of globalization intensified after World War II, and especially in the late 20th century with the introduction of new technologies that enabled vast volumes of capital and goods to circulate globally. The globalization of investment and production means that capital is increasingly able to shift production around the world to where labour costs are cheapest and profit greatest. In fact, as Ulrich Beck (1944-2015) put it, the effect of globalization has been to “conjure away distance” on a variety of different levels (2000, p. 20). He has argued that political actors no longer:

live and act in the self-enclosed spaces of national states and their respective national societies. Globalization means that borders become markedly less relevant to everyday behaviour in the various dimensions of economics, information, ecology, technology, cross-cultural conflict and civil society. (2000, p. 20)

The terrain on which corporate, political, environmental, and other types of decisions are made is no longer confined to the boundaries of the state, which diminishes the ability of national governments to independently control economic and foreign policy. Thus, globalization represents a weakening of the autonomy and power of states. Neoliberalism is not only an internal domestic response to the economic crises and fall in the rates of profit, which began in the late 1960s, but also is a response to the ever more competitive global market for capital. Neoliberal policy is presented as a way to attract increasingly fickle global capital by making entire countries more “competitive.” The result, as David Harvey (b. 1935) forcefully argues, has been to massively shift the balance of power to the economic elites of the global capitalist class (2005, pp. 16–19). As a result wealth has also been redistributed upwards.

The changing configuration of global capitalism and politics has been described by some as the reemergence of empire (Hardt & Negri, 2000). Rather than a sovereign state system of unique and independent nation-states, in many ways the global order is better described today as a single unit within which state sovereignty has been transferred to a higher entity (Negri, 2004, p. 59). Numerous trade agreements have harmonized economies and removed borders that restrict the flow of capital and goods, and in recent decades frequent global “police actions” and trade embargoes have been enacted by various “coalitions of the willing” to enforce peace or intervene in domestic policy (in, for example, Iraq, Yugoslavia, Somalia, Afghanistan, Iran, Libya, and Syria, etc.). Similarly, the Kyoto Protocol on climate change or the Ottawa Treaty on landmines are examples of global initiatives that blur the boundaries of nation states. Empire in this sense refers to a new supra-national, global form of sovereignty whose “territory” is the entire globe. Antonio Negri (b. 1933) makes the point that this is not the same as saying that the world is dominated and controlled by the United States; rather, power is exercised through a “network” of dominant nation-states, supranational institutions (e.g., the UN, IMF, WTO, G8, NATO, etc.) and major capitalist corporations (Hardt & Negri, 2000; Negri, 2004). Empire, rather than being a form of imperialism like that which dominated in the era of colonialism, is a new political form that has emerged in response to the dynamics of global capitalism.

6.3.2 Neoliberalism as Style of Government

Neoliberalism is fascinating sociologically because, aside from being a type of economic policy, it signals a new way of governing individuals. This has broad implications outside of the narrow parameters of neoliberal policies like tax cuts, deregulation, and reducing the state’s role in the economy. Neoliberalism also refers to a more general strategy of governing individual conduct in a number of different areas including health, employment, education, security, and crime control. In an interesting way, it governs individuals through their exercise of freedom and free choice. Whereas the welfare state has been frequently criticized by neoliberals for fostering a culture of welfare dependency and a “one size fits all” concept of government services, the new types of neoliberal strategies emphasize various ways to create active and independent entrepreneurial citizens (Rose, 1999). Thus, the idea of markets is important because markets are mechanisms that regulate and discipline people through the free choices that they make. If they make good choices they profit; if they make bad choices they pay.

One thing the “neo” (or “new”) in neo-liberalism signifies is the extension of the idea of the market into areas of life where no markets existed before. For example, the provision of care for the disabled used to be provided through state institutionalization. Today, it is common to find a model of care like “individualized funding” (See, for example, Community Living BC, 2013). The state provides families of the disabled with direct payments that they use to pay for care providers who they choose after doing their own research on appropriate therapies or treatments. A market for caregivers and therapists is created, based on an assumption that this is a more efficient model for matching the skills of care contractors with the needs of the disabled. Rather than care being provided as needed, individuals or families are encouraged or obliged to become active consumers of therapeutic services and to make calculative decisions from an array of market choices. The families need to demonstrate their competent use of the money through formal mechanisms like budgets, audits, targets, minimal standards, and contracts but otherwise are free to choose the services they want.

In practice these policies are often means to further reduce the overall amount of state expenditure for the disabled and their families, but as a method for governing the lives of individuals, they represent a fundamental shift from the notion of individuals as citizens with rights to individuals as agents who must independently exercise free choice, enterprise, and self-responsibility. Even though these types of policies, when properly funded, have many positive features for those with the wherewithal to take advantage of the expansion of choice (Sandborn, 2012), they represent a significant shift in the strategies of government. Thus, neoliberalism is both a macro-level economic policy, but it is also a strategy designed to change the type of relationship we have with ourselves and the concept of ourselves as citizens.

One of the consequences of the rationalization of everyday life is stress. In 2010, 27 percent of working adults in Canada described their day-to-day lives as highly stressful (Crompton, 2011). Twenty-three percent of all Canadians aged 15 and older reported that most days were highly stressful in 2013 (Statistics Canada, 2014). In the case of stress, rationalization is a double-edged sword in that it allows people to get more things done per unit of time more efficiently in order to “save time,” but ironically efficiency–as a means to an end–tends to replace other goals in life and becomes an end in itself. The focus on efficiency means that people regard time as a kind of limited resource in which to achieve a maximum number of activities. The irrationality in rationalization is: Saving time for what? Are we able to take time for activities (including sleep) which replenish us or enrich us? Even the notions of “taking time” or “spending quality time” with someone uses the metaphor of time as a kind of expenditure in which we use up a limited resource. Stress is in many respects a product of our modern “rational” relationship to time. As we can see in the table below, for a significant number of people, there is simply not enough time in the day to accomplish what we set out to do.

| [Skip Table] | ||||||||

| Perceptions of time | Age group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 and over | 15 to 24 | 25 to 34 | 35 to 44 | 45 to 54 | 55 to 64 | 65 to 74 | 75 and over | |

| Do you plan to slow down in the coming year? | 19% | 13% | 16% | 21% | 22% | 23% | 16% | 20% |

| Do you consider yourself a workaholic? | 25% | 22% | 29% | 31% | 28% | 23% | 18% | 14% |

| When you need more time, do you tend to cut back on your sleep? | 46% | 63% | 60% | 59% | 45% | 31% | 20% | 15% |

| At the end of the day, do you often feel that you have not accomplished what you had set out to do? | 41% | 34% | 46% | 48% | 46% | 40% | 29% | 35% |

| Do you worry that you don’t spend enough time with your family or friends? | 36% | 34% | 47% | 53% | 41% | 27% | 14% | 10% |

| Do you feel that you’re constantly under stress trying to accomplish more than you can handle? | 34% | 35% | 41% | 47% | 40% | 27% | 15% | 10% |

| Do you feel trapped in a daily routine? | 34% | 33% | 41% | 46% | 40% | 28% | 15% | 15% |

| Do you feel that you just don’t have time for fun any more? | 29% | 20% | 36% | 43% | 38% | 23% | 11% | 11% |

| Do you often feel under stress when you don’t have enough time? | 54% | 65% | 66% | 69% | 59% | 41% | 22% | 16% |

| Would you like to spend more time alone? | 22% | 19% | 30% | 35% | 24% | 15% | 9% | 7% |

| Note: The percentages represent the proportion of persons who answered “yes” to the questions on perceptions of time. Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2010 (Statistics Canada, 2011). |

||||||||

6.3.3 The Commodity, Commodification, and Consumerism as a Way of Life

The commodity is simply an object, service, or a “good” that has been produced for sale on the market. Commodification is the process through which objects, services, or goods are increasingly turned into commodities, so they become defined more in terms of their marketability and profitability than by their intrinsic characteristics. Prior to the invention of the commodity market, economic life revolved around bartering or producing for immediate consumption. Real objects like wool or food were exchanged for other real objects or were produced for immediate consumption according to need. The commodity introduces a strange factor into this equation because in the marketplace objects are exchanged for money. They are produced in order to be sold in the market. Their value is determined not just in regard to their unique qualities, their purpose, or their ability to satisfy a need (i.e., their “use value”), but also their monetary value or “exchange value” (i.e., their price). When we ask what something is worth, we are usually referring to its price.

This monetization of value is strange in the first place because the medium of money allows for incomparable, concrete things or use values to be quantified and compared. Twenty dollars will get you a chicken, a novel, or a hammer; these fundamentally different things all become equivalent. It is strange in the second place because the use of money to define the value of commodities makes the commodity appear to stand alone, as if its value was independent of the labour that produced it or the needs it was designed to satisfy. We see the object and imagine the qualities it will endow us with: a style, a fashionability, a personality type, or a tribal affiliation (e.g., PC people vs. Mac people). We do not recognize the labour and the social relationships of work that produced it, nor the social relationships that tie us to its producers when we purchase it. Karl Marx (1818 – 1883) called this phenomenon commodity fetishism (1867).

With the increased importance of maintaining high levels of commodity turn over and consumption that emerged with the system of late capitalism, commodity fetishism plays a powerful role in producing ever new wants and desires. Consumerism becomes a way of life. Consumerism refers to the way in which we define ourselves in terms of the commodities we purchase. To the degree that our identities become defined by the pattern of our consumer preferences, the commodity no longer exists to serve our needs but to define our needs. As Barbara Kruger put it, the motto of consumer culture is not “I think therefore I am” but “I shop therefore I am.” Thinking is precisely what consumerism entices us not to do, except in so far as we calculate the prices of things.

6.4 Technological Innovation, Media and Society

While most people probably picture computers and cell phones when the subject of technology comes up, technology is not merely a product of the modern era. For example, fire and stone tools were important forms of technology developed during the Stone Age. Just as the availability of digital technology shapes how we live today, the creation of stone tools changed how premodern humans lived and how well they ate. From the first calculator, invented in 2400 BCE in Babylon in the form of an abacus, to the predecessor of the modern computer, created in 1882 by Charles Babbage, all of our technological innovations are advancements on previous iterations. And indeed, all aspects of our lives today are influenced by technology. In agriculture, the introduction of machines that can till, thresh, plant, and harvest greatly reduced the need for manual labour, which in turn meant there were fewer rural jobs, which led to the urbanization of society, as well as lowered birthrates because there was less need for large families to work the farms. In the criminal justice system, the ability to ascertain innocence through DNA testing has saved the lives of people on death row. The examples are endless: technology plays a role in absolutely every aspect of our lives.

How many good friends do you have? How many people do you meet for coffee or a movie? How many would you call with news about an illness or invite to your wedding? Now, how many “friends” do you have on Facebook? Technology has changed how we interact with each other. It has turned “friend” into a verb and has made it possible to share mundane news (“My dog just threw up under the bed! Ugh!”) with hundreds or even thousands of people who might know you only slightly, if at all. Through the magic of Facebook, you might know about an old elementary school friend’s new job before her mother does. By thinking of everyone as fair game in networking for personal gain, we can now market ourselves professionally to the world with LinkedIn.

At the same time that technology is expanding the boundaries of our social circles, various media are also changing how we perceive and interact with each other. We do not only use Facebook to keep in touch with friends; we also use it to “like” certain TV shows, products, or celebrities. Even television is no longer a one-way medium but an interactive one. We are encouraged to tweet, text, or call in to vote for contestants in everything from singing competitions to matchmaking endeavours — bridging the gap between our entertainment and our own lives.

How does technology change our lives for the better? Or does it? When you tweet a social cause or cut and paste a status update about cancer awareness on Facebook, are you promoting social change? Does the immediate and constant flow of information mean we are more aware and engaged than any society before us? Or are TV reality shows and talent competitions today’s version of ancient Rome’s “bread and circuses” — distractions and entertainment to keep the lower classes indifferent to the inequities of our society? Do media and technology liberate us from gender stereotypes and provide us with a more cosmopolitan understanding of each other, or have they become another tool in promoting misogyny? Is ethnic and gay and lesbian intolerance being promoted through a ceaseless barrage of minority stereotyping in movies, video games, and websites?

These are some of the questions that interest sociologists. How might we examine these issues from a sociological perspective? A structural functionalist would probably focus on what social purposes technology and media serve. For example, the web is both a form of technology and a form of media, and it links individuals and nations in a communication network that facilitates both small family discussions and global trade networks. A functionalist would also be interested in the manifest functions of media and technology, as well as their role in social dysfunction. Someone applying the critical perspective would probably focus on the systematic inequality created by differential access to media and technology. For example, how can Canadians be sure the news they hear is an objective account of reality, unsullied by moneyed political interests? Someone applying the interactionist perspective to technology and the media might seek to understand the difference between the real lives we lead and the reality depicted on “reality” television shows, such as the U.S., based but Canadian MTV production Jersey Shore, with up to 800,000 Canadian viewers (Vlessing, 2011).

It is easy to look at the latest sleek tiny Apple product and think that technology is only recently a part of our world. But from the steam engine to the most cutting-edge robotic surgery tools, technology describes the application of science to address the problems of daily life. We might look back at the enormous and clunky computers of the 1970s that had about as much storage as an iPod Shuffle and roll our eyes in disbelief. But chances are 30 years from now our skinny laptops and MP3 players will look just as archaic.

6.4.1 Technological Inequality

As with any improvement to human society, not everyone has equal access. Technology, in particular, often creates changes that lead to ever greater inequalities. In short, the gap gets wider faster. This technological stratification has led to a new focus on ensuring better access for all.

There are two forms of technological stratification. The first is differential class-based access to technology in the form of the digital divide. This digital divide has led to the second form, a knowledge gap, which is, as it sounds, an ongoing and increasing gap in information for those who have less access to technology. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines the digital divide as “the gap between individuals, households, businesses and geographic areas at different socio-economic levels with regard to both their opportunities to access information and communication technology (ICTs) and to their use of the Internet for a wide variety of activities.” (OECD, 2001, p.5) For example, students in well-funded schools receive more exposure to technology than students in poorly funded schools. Those students with more exposure gain more proficiency, making them far more marketable in an increasingly technology-based job market, leaving our society divided into those with technological knowledge and those without. Even as we improve access, we have failed to address an increasingly evident gap in e-readiness, the ability to sort through, interpret, and process knowledge (Sciadas, 2003).

Since the beginning of the millennium, social science researchers have tried to bring attention to the digital divide, the uneven access to technology along race, class, and geographic lines. The term became part of the common lexicon in 1996, when then U.S. Vice-President Al Gore used it in a speech. In part, the issue of the digital divide had to do with communities that received infrastructure upgrades that enabled high-speed internet access, upgrades that largely went to affluent urban and suburban areas, leaving out large swaths of the country.

At the end of the 20th century, technology access was also a big part of the school experience for those whose communities could afford it. Early in the millennium, poorer communities had little or no digital technology access, while well-off families had personal computers at home and wired classrooms in their schools. In Canada we see a clear relationship between youth computer access and use and socioeconomic status in the home. As one study points out, about a third of the youth whose parents have no formal or only elementary school education have no computer in their home compared to 13% of those whose parent has completed high school (Looker and Thiessen, 2003). In the 2000s, however, the prices for low-end computers dropped considerably, and it appeared the digital divide was ending. And while it is true that internet usage, even among those with low annual incomes, continues to grow, it would be overly simplistic to say that the digital divide has been completely resolved.

In fact, new data from the Pew Research Center (2011) suggest the emergence of a new divide. As technological devices get smaller and more mobile, larger percentages of minority groups are using their phones to connect to the internet. In fact, about 50% of people in these minority groups connect to the web via such devices, whereas only one-third of whites do (Washington, 2011). And while it might seem that the internet is the internet, regardless of how you get there, there is a notable difference. Tasks like updating a résumé or filling out a job application are much harder on a cell phone than on a wired computer in the home. As a result, the digital divide might not mean access to computers or the internet, but rather access to the kind of online technology that allows for empowerment, not just entertainment (Washington, 2011).

Liff and Shepard (2004) found that although the gender digital divide has decreased in the sense of access to technology, it remained in the sense that women, who are accessing technology shaped primarily by male users, feel less confident in their internet skills and have less internet access at both work and home. Finally, Guillen and Suarez (2005) found that the global digital divide resulted from both the economic and sociopolitical characteristics of countries.

6.4.2 Planned Obsolescence: Technology That’s Built to Crash

Chances are your mobile phone company, as well as the makers of your DVD player and MP3 device, are all counting on their products to fail. Not too quickly, of course, or consumers would not stand for it — but frequently enough that you might find that when the built-in battery on your iPod dies, it costs far more to fix it than to replace it with a newer model. Or you find that the phone company emails you to tell you that you’re eligible for a free new phone because yours is a whopping two years old. Appliance repair people say that while they might be fixing some machines that are 20 years old, they generally are not fixing the ones that are seven years old; newer models are built to be thrown out. This is called planned obsolescence, and it is the business practice of planning for a product to be obsolete or unusable from the time it is created (The Economist, 2009).

To some extent, this is a natural extension of new and emerging technologies. After all, who is going to cling to an enormous and slow desktop computer from 2000 when a few hundred dollars can buy one that is significantly faster and better? But the practice is not always so benign. The classic example of planned obsolescence is the nylon stocking. Women’s stockings — once an everyday staple of women’s lives — get “runs” or “ladders” after a few wearings. This requires the stockings to be discarded and new ones purchased. Not surprisingly, the garment industry did not invest heavily in finding a rip-proof fabric; it was in their best interest that their product be regularly replaced.

Those who use Microsoft Windows might feel that they, like the women who purchase endless pairs of stockings, are victims of planned obsolescence. Every time Windows releases a new operating system, there are typically not many changes that consumers feel they must have. However, the software programs are upwardly compatible only. This means that while the new versions can read older files, the old version cannot read the newer ones. Even the ancillary technologies based on operating systems are only compatible upward. In 2014, the Windows XP operating system, off the market for over five years, stopped being supported by Microsoft when in reality it has not been supported by newer printers, scanners, and software add-ons for many years.

Ultimately, whether you are getting rid of your old product because you are being offered a shiny new free one (like the latest smartphone model), or because it costs more to fix than to replace (like an iPod), or because not doing so leaves you out of the loop (like the Windows system), the result is the same. It might just make you nostalgic for your old Sony Walkman and VCR.

But obsolescence gets even more complex. Currently, there is a debate about the true cost of energy consumption for products. This cost would include what is called the embodied energy costs of a product. Embodied energy is the calculation of all the energy costs required for the resource extraction, manufacturing, transportation, marketing, and disposal of a product. One contested claim is that the energy cost of a single cell phone is about 25% of the cost of a new car. We love our personal technology but it comes with a cost. Think about the incredible social organization undertaken from the idea of manufacturing a cell phone through to its disposal after about two years of use (Kedrosky, 2011).

6.4.3 Media and Technology in Society

Technology and the media are interwoven, and neither can be separated from contemporary society in most developed and developing nations. Media is a term that refers to all print, digital, and electronic means of communication. From the time the printing press was created (and even before), technology has influenced how and where information is shared. Today, it is impossible to discuss media and the ways that societies communicate without addressing the fast-moving pace of technology. Twenty years ago, if you wanted to share news of your baby’s birth or a job promotion, you phoned or wrote letters. You might tell a handful of people, but probably you would not call up several hundred, including your old high school chemistry teacher, to let them know. Now, by tweeting or posting your big news, the circle of communication is wider than ever. Therefore, when we talk about how societies engage with technology we must take media into account, and vice versa.

Technology creates media. The comic book you bought your daughter at the drugstore is a form of media, as is the movie you rented for family night, the internet site you used to order dinner online, the billboard you passed on the way to get that dinner, and the newspaper you read while you were waiting to pick up your order. Without technology, media would not exist; but remember, technology is more than just the media we are exposed to.

Categorizing Technology

There is no one way of dividing technology into categories. Whereas once it might have been simple to classify innovations such as machine-based or drug-based or the like, the interconnected strands of technological development mean that advancement in one area might be replicated in dozens of others. For simplicity’s sake, we will look at how the U.S. Patent Office, which receives patent applications for nearly all major innovations worldwide, addresses patents. This regulatory body will patent three types of innovation. Utility patents are the first type. These are granted for the invention or discovery of any new and useful process, product, or machine, or for a significant improvement to existing technologies. The second type of patent is a design patent. Commonly conferred in architecture and industrial design, this means someone has invented a new and original design for a manufactured product. Plant patents, the final type, recognize the discovery of new plant types that can be asexually reproduced. While genetically modified food is the hot-button issue within this category, farmers have long been creating new hybrids and patenting them. A more modern example might be food giant Monsanto, which patents corn with built-in pesticide (U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, 2011).

Such evolving patents have created new forms of social organization and disorganization. Efforts by Monsanto to protect its patents have led to serious concerns about who owns the food production system, and who can afford to participate globally in this new agrarian world. This issue was brought to a head in a landmark Canadian court case between Monsanto and Saskatchewan farmer Percy Schmeiser. Schmeiser found Monsanto’s genetically modified “Roundup Ready” canola growing on his farm. He saved the seed and grew his own crop, but Monsanto tried to charge him licensing fees because of their patent. Dubbed a true tale of David versus Goliath, both sides are claiming victory (Mercola, 2011; Monsanto, N.d.). What is important to note is that through the courts, Monsanto established its right to the ownership of its genetically modified seeds even after multiple plantings. Each generation of seeds harvested still belonged to Monsanto. For millions of farmers globally, such a new market model for seeds represents huge costs and dependence on a new and evolving corporate seed supply system.

Anderson and Tushman (1990) suggest an evolutionary model of technological change, in which a breakthrough in one form of technology leads to a number of variations. Once those are assessed, a prototype emerges, and then a period of slight adjustments to the technology, interrupted by a breakthrough. For example, floppy disks were improved and upgraded, then replaced by zip disks, which were in turn improved to the limits of the technology and were then replaced by flash drives. This is essentially a generational model for categorizing technology, in which first-generation technology is a relatively unsophisticated jumping-off point leading to an improved second generation, and so on.

Types of Media and Technology

Media and technology have evolved hand in hand, from early print to modern publications, from radio to television to film. New media emerge constantly, such as we see in the online world.

Print Newspaper

Early forms of print media, found in ancient Rome, were hand-copied onto boards and carried around to keep the citizenry informed. With the invention of the printing press, the way that people shared ideas changed, as information could be mass produced and stored. For the first time, there was a way to spread knowledge and information more efficiently; many credit this development as leading to the Renaissance and ultimately the Age of Enlightenment. This is not to say that newspapers of old were more trustworthy than the Weekly World News and National Enquirer are today. Sensationalism abounded, as did censorship that forbade any subjects that would incite the populace.

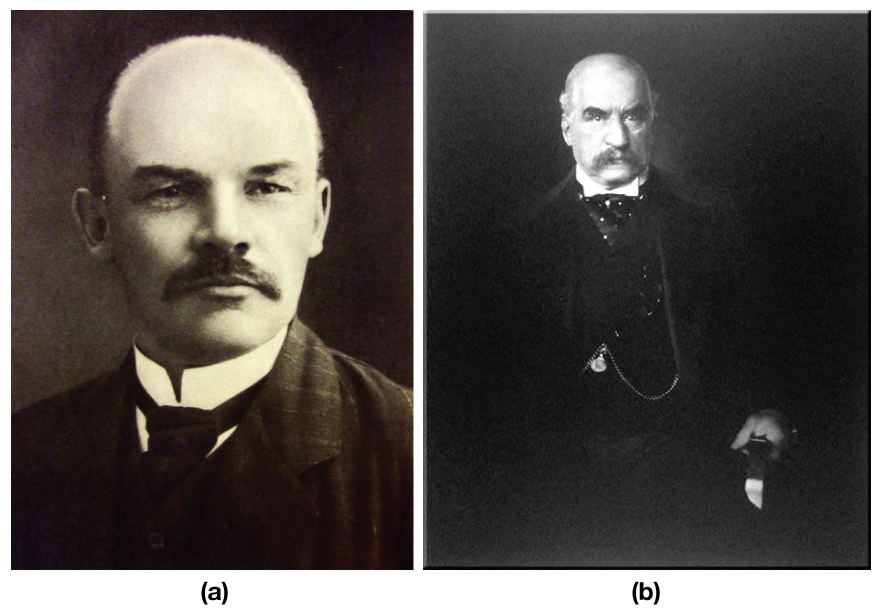

The invention of the telegraph, in the mid-1800s, changed print media almost as much as the printing press. Suddenly information could be transmitted in minutes. As the 19th century became the 20th, American publishers such as Hearst redefined the world of print media and wielded an enormous amount of power to socially construct national and world events. Of course, even as the Canadian media empires of Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook) and Roy Thomson or the U.S. empires of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer were growing, print media also allowed for the dissemination of counter-cultural or revolutionary materials. Internationally, Vladimir Lenin’s Irksa (The Spark) newspaper was published in 1900 and played a role in Russia’s growing communist movement (World Association of Newspapers, 2004).

With the invention and widespread use of television in the mid-20th century, newspaper circulation steadily dropped off, and in the 21st century, circulation has dropped further as more people turn to internet news sites and other forms of new media to stay informed. This shift away from newspapers as a source of information has profound effects on societies. When the news is given to a large diverse conglomerate of people, it must (to appeal to them and keep them subscribing) maintain some level of broad-based reporting and balance. As newspapers decline, news sources become more fractured, so that the audience can choose specifically what it wants to hear and what it wants to avoid. But the real challenge to print newspapers is that revenue sources are declining much faster than circulation is dropping. With an anticipated decline in revenue of over 20% by 2017, the industry is in trouble (Ladurantaye, 2013). Unable to compete with digital media, large and small newspapers are closing their doors across the country. Something to think about is the concept of embodied energy mentioned earlier. The print newspapers are responsible for much of these costs internally. Digital media has downloaded much of these costs onto the consumer through personal technology purchases.

Television and Radio

Radio programming obviously preceded television, but both shaped people’s lives in much the same way. In both cases, information (and entertainment) could be enjoyed at home, with a kind of immediacy and community that newspapers could not offer. Prime Minister Mackenzie King broadcast his radio message out to Canada in 1927. He later used radio to promote economic cooperation in response to the growing socialist agitation against the abuses of capitalism both outside and within Canada (McGivern, 1990).

Radio was the first “live” mass medium. People heard about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor as it was happening. Hockey Night in Canada was first broadcast live in 1932. Even though people were in their own homes, media allowed them to share these moments in real time. Unlike newspapers, radio is a survivor. As Canada’s globally renowned radio marketing guru Terry O’Reilly asserts, radio survives “because it is such a ‘personal’ medium. Radio is a voice in your ear. It is a highly personal activity.” He also points out that “radio is local. It broadcasts news and programming that is mostly local in nature. And through all the technological changes happening around radio, and in radio, be it AM moving to FM moving to satellite radio and internet radio, basic terrestrial radio survives into another day” (O’Reilly, 2014). This same kind of separate-but-communal approach occurred with other entertainment too. School-aged children and office workers still gather to discuss the previous night’s instalment of a serial television or radio show.

The influence of Canadian television has always reflected a struggle with the influence of U.S. television dominance, the language divide, and strong federal government intervention into the industry for political purposes. There were thousands of televisions in Canada receiving U.S. broadcasting a decade before the first two Canadian stations began broadcasting in 1952 (Wikipedia, N.d.). Public television, in contrast, offered an educational nonprofit alternative to the sensationalization of news spurred by the network competition for viewers and advertising dollars. Those sources — PBS (Public Broadcasting Service) in the United States, the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation), and CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation), which straddled the boundaries of public and private, garnered a worldwide reputation for quality programming and a global perspective. Al Jazeera, the Arabic independent news station, has joined this group as a similar media force that broadcasts to people worldwide.

The impact of television on North American society is hard to overstate. By the late 1990s, 98% of homes had at least one television set. All this television has a powerful socializing effect, with these forms of visual media providing reference groups while reinforcing social norms, values, and beliefs.

Film

The film industry took off in the 1930s, when colour and sound were first integrated into feature films. Like television, early films were unifying for society: As people gathered in theatres to watch new releases, they would laugh, cry, and be scared together. Movies also act as time capsules or cultural touchstones for society. From tough-talking Clint Eastwood to the biopic of Facebook founder and Harvard dropout Mark Zuckerberg, movies illustrate society’s dreams, fears, and experiences. The film industry in Canada has struggled to maintain its identity while at the same time embracing the North American industry by actively competing for U.S. film production in Canada. Today, a significant number of the recognized trades occupations requiring apprenticeship and training are in the film industry. While many North Americans consider Hollywood the epicentre of moviemaking, India’s Bollywood actually produces more films per year, speaking to the cultural aspirations and norms of Indian society.

New Media

New media encompasses all interactive forms of information exchange. These include social networking sites, blogs, podcasts, wikis, and virtual worlds. The list grows almost daily. New media tends to level the playing field in terms of who is constructing it (i.e., creating, publishing, distributing, and accessing information) (Lievrouw and Livingstone, 2006), as well as offering alternative forums to groups unable to gain access to traditional political platforms, such as groups associated with the Arab Spring protests (van de Donk et al., 2004). However, there is no guarantee of the accuracy of the information offered. In fact, the immediacy of new media coupled with the lack of oversight means that we must be more careful than ever to ensure our news is coming from accurate sources.

New media is already redefining information sharing in ways unimaginable even a decade ago. New media giants like Google and Facebook have recently acquired key manufacturers in the aerial drones market creating an exponential ability to reach further in data collecting and dissemination. While the corporate line is benign enough, the implications are much more profound in this largely unregulated arena of aerial monitoring. With claims of furthering remote internet access, “industrial monitoring, scientific research, mapping, communications, and disaster assistance,” the reach is profound (Claburn, 2014). But when aligned with military and national surveillance interests these new technologies become largely exempt from regulations and civilian oversight.

Technology, Media and Product Advertising

Companies use advertising to sell to us, but the way they reach us is changing. Increasingly, synergistic advertising practices ensure you are receiving the same message from a variety of sources. For example, you may see billboards for Molson’s on your way to a stadium, sit down to watch a game preceded by a beer commercial on the big screen, and watch a halftime ad in which people are frequently shown holding up the trademark bottles. Chances are you can guess which brand of beer is for sale at the concession stand.