9 Module 9: Families and Family Life

Learning Objectives

- Define the institution of marriage and “the family” and describe how the two are related.

- Differentiate among micro, meso, and macro approaches to the family.

- Outline how the relationship between marriage and family has changed over time.

- Discuss the effect of the family life cycle on the quality of family experience.

- Describe the different forms of the family including the nuclear family, single-parent families, cohabitation, same-sex couples, childfree and childless couples and single individuals.

- Describe and discuss the social and interpersonal impact of divorce.

- Describe the problems of family abuse and discuss whether corporal punishment is a form of abuse.

- Compare and contrast functionalist, critical, and symbolic interactionist perspectives on the modern family.

9.0 Introduction to Marriage and Family

Christina and James met in college and have been dating for more than five years. For the past two years, they have been living together in a condo they purchased jointly. While Christina and James were confident in their decision to enter into a commitment (such as a 20-year mortgage), they are unsure if they want to enter into marriage. The couple had many discussions about marriage and decided that it just did not seem necessary. Was it not only a piece of paper? Did not half of all marriages end in divorce?

Neither Christina nor James had seen much success with marriage while growing up. Christina was raised by a single mother. Her parents never married, and her father has had little contact with the family since she was a toddler. Christina and her mother lived with her maternal grandmother, who often served as a surrogate parent. James grew up in a two-parent household until age seven, when his parents divorced. He lived with his mother for a few years, and then later with his mother and her boyfriend until he left for college. James remained close with his father who remarried and had a baby with his new wife.

Recently, Christina and James have been thinking about having children and the subject of marriage has resurfaced. Christina likes the idea of her children growing up in a traditional family, while James is concerned about possible marital problems down the road and negative consequences for the children should that occur. When they shared these concerns with their parents, James’s mom was adamant that the couple should get married. Despite having been divorced and having a live-in boyfriend of 15 years, she believes that children are better off when their parents are married. Christina’s mom believes that the couple should do whatever they want but adds that it would “be nice” if they wed. Christina and James’s friends told them, married or not married, they would still be a family.

Christina and James’s scenario may be complicated, but it is representative of the lives of many young couples today, particularly those in urban areas (Useem, 2007). Statistics Canada (2012) reports that the number of unmarried, common-law couples grew by 35% between 2001 and 2011, to make up a total of 16.7% of all families in Canada. Some may never choose to wed (Jayson, 2008). With fewer couples marrying, the traditional Canadian family structure is becoming less common. Nevertheless, although the percentage of traditional married couples has declined as a proportion of all families, at 67% of all families, it is still by far the predominant family structure. In the following infographic additional changes in the structure of modern Canadian families are highlighted, portraying the institution of the family in Canada as a changing and dynamic institution.

9.1 Marriage and Family: Central and Evolving Social Institutions

9.1.1 What is Marriage?

Marriage and family are key structures and foundational institutions in most societies. While the two institutions have historically been closely linked in Canadian culture, their connection is becoming more complex. The relationship between marriage and family is often taken for granted in the popular imagination but with the increasing diversity of family forms in the 21st century their relationship needs to be reexamined.

What is marriage? Different people define it in different ways. Not even sociologists are able to agree on a single meaning. For our purposes, we will define marriage as a legally recognized social contract between two people, traditionally based on a sexual relationship, and implying a permanence of the union. In creating an inclusive definition, we should also consider variations, such as whether a formal legal union is required (think of common-law marriage and its equivalents), or whether more than two people can be involved (consider polygamy). Other variations on the definition of marriage might include whether spouses are of opposite sexes or the same sex, and how one of the traditional expectations of marriage (to produce children) is understood today.

Sociologists are interested in the relationship between the institution of marriage and the institution of family because, historically, marriages are what create a family, and families are the most basic social unit upon which society is built. Both marriage and family create status roles that are sanctioned by society. While marriage is a central institution in society, its primary purpose, form and content have varied across cultures, and over time.

Throughout most of history, erotic love or romantic love was not considered a suitable basis for marriage. Marriages were typically arranged by families through negotiations designed to increase wealth, property, or prestige, establish ties, or gain political advantages. In modern individualistic societies on the other hand, romantic love is seen as the essential basis for marriage. In response to the question, “If a man (woman) had all the other qualities you desired, would you marry this person if you were not in love with him (her)?” only 4% of Americans and Brazilians, 5% of Australians, 6% of Hong Kong residents, and 7% of British residents said they would — compared to 49% of Indians and 50% of Pakistanis (Levine, Sato, Hashimoto, and Verma, 1995). Despite the emphasis on romantic love, it is also recognized to be an unstable basis for long-term relationships as the feelings associated with it are transitory.

What exactly is romantic love? Neuroscience describes it as one of the central brain systems that have evolved to ensure mating, reproduction, and the perpetuation of the species (Fisher, 1992). Alongside the instinctual drive for sexual satisfaction, (which is relatively indiscriminate in its choice of object), and companionate love, (the long term attachment to another which enables mates to remain together at least long enough to raise a child through infancy), romantic love is the intense attraction to a particular person that focuses “mating energy” on a single person at a single time. It manifests as a seemingly involuntary, passionate longing for another person in which individuals experience obsessiveness, craving, loss of appetite, possessiveness, anxiety, and compulsive, intrusive thoughts. In studies comparing functional MRI brain scans of maternal attachment to children and romantic attachment to a loved one, both types of attachment activate oxytocin and vasopressin receptors in regions in the brain’s reward system while suppressing regions associated with negative emotions and critical judgement of others (Bartels and Zeki, 2004; Acevedo, Aron, Fisher and Brown, 2012). In this respect, romantic love shares many physiological features in common with addiction and addictive behaviours.

In a sociological context, the physiological manifestations of romantic love are associated with a number of social factors. Love itself might be described as the general force of attraction that draws people together; a principle agency that enables society to exist. As Freud defined it, love in the form of eros, was the force that strove to “form living substance into ever greater unities, so that life may be prolonged and brought to higher development” (Freud cited in Marcuse, 1955). In this sense, as Erich Fromm put it, “[l]ove is not primarily a relationship to a specific person; it is an attitude, an orientation of character which determines the relatedness of a person to the world as a whole, not toward one “object” of love” (Fromm, 1956). Fromm argues therefore that love can take many forms: brotherly love, the sense of care for another human; motherly love, the unconditional love of a mother for a child; erotic love, the desire for complete fusion with another person; self-love, the ability to affirm and accept oneself; and love of God, a sense of universal belonging or union with a higher or sacred order.

Only when the object of love is individualized in another, does it come to form the basis of erotic or intimate relationships. In this sense, romantic love can be defined as the desire for emotional union with another person (Fisher, 1992). In Robert Sternberg’s (1986) triangular theory of love, romantic love consists of three components: passion or erotic attraction (limerance); intimacy or feelings of bonding, sharing, closeness, and connectedness; and commitment or deliberate choice to enter into and remain in a relationship. The three components vary independently in long term relationships: passion starts off at high levels but drops off as the partner no longer has the same arousal value, intimacy decreases gradually as the relationship becomes more predictable, while commitment increases gradually at first, then more rapidly as the relationship intensifies, and eventually levels off. This suggests that for couples who remain together, romantic love eventually develops into companionate love characterized by deep friendship, comfortable companionship, and shared interests, but not necessarily intense attraction or sexual desire.

Although romantic love is often characterized as an involuntary force that sweeps people away, mate selection nevertheless involves an implicit or explicit cost/benefit analysis that affects who falls in love with whom. In particular, people tend to select mates of a similar social status from within their own social group. The selection process is influenced by three sociological variables (Kalmijn, 1998). Firstly, potential mates assess each others’ socioeconomic resources, like income potential or family wealth, and cultural resources, like education, taste, worldview, and values, to maximize the value or rewards the relationship will bring to them. Secondly, third parties like family, church, or community members tend intervene to prevent people from choosing partners from outside their community or social group because this threatens group cohesion and homogeneity. Thirdly, demographic variables that effect “local marriage markets” — typically places like schools, workplaces, bars, clubs, and neighborhoods where potential mates can meet — will also affect mate choice. Due to probability, people from large or concentrated social groups have more chance to choose a partner from within their group than do people from smaller or more dispersed groups. Other demographic or social factors like war or economic conditions also affect the ratio of males to females or the distribution of ages in a community, which in turn affects the likelihood of finding a mate inside of one’s social group. Mate selection is therefore not as random as the story of Cupid’s arrow suggests.

9.1.2 What is family?

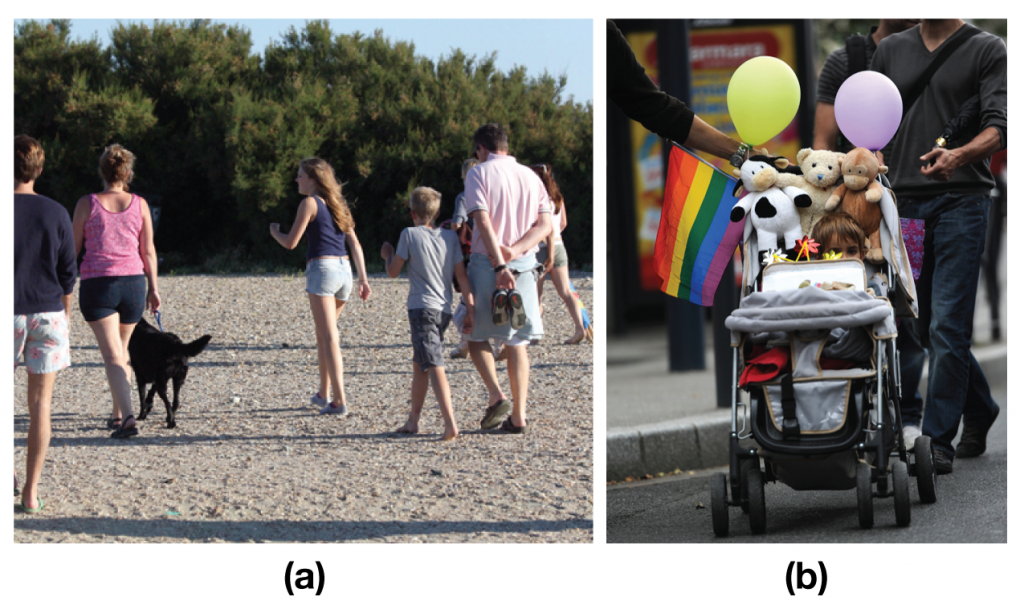

A husband, a wife, and two children — maybe even a pet — served as the model for the traditional Canadian family for most of the 20th century. But what about families that deviate from this model, such as a single-parent household or a homosexual couple without children? Should they be considered families as well?

The question of what constitutes a family is a prime area of debate in family sociology. It is also a hotly contested topic in the domains of politics and religion. Social conservatives tend to define the family in terms of a “traditional” nuclear family structure with each family member filling a certain role (like father, mother, or child). Sociologists, on the other hand, tend to define family more in terms of the manner in which members relate to one another rather than in terms of a rigid and static configuration of status roles. Here, we will define family as a socially recognized group joined by blood relations, marriage, or adoption, that forms an emotional connection and serves as an economic unit of society. Sociologists also identify different types of families based on how one enters into them. A family of orientation refers to the family into which a person is born. A family of procreation describes one that is formed through marriage. These distinctions have cultural significance related to issues of lineage (the difference between patrilineal and matrilineal descent for example).

Based on Simmel’s distinction between the form and content of social interaction, we can analyze the family as a social form that comes into existence around five different contents or interests: sexual activity, economic cooperation, reproduction, socialization of children, and emotional support. As we might expect from Simmel’s analysis, the types of family form in which all or some of these contents are expressed are diverse: nuclear families, polygamous families, extended families, same-sex parent families, single-parent families, blended families, and zero-child families, etc. However, the forms that families take are not random; rather, these forms are determined by cultural traditions, social structures, economic pressures, and historical transformations. They also are subject to intense moral and political debate about the definition of the family, the “decline of the family,” or the policy options to best support the well-being of children. In these debates, sociology demonstrates its practical side as a discipline that is capable of providing the factual knowledge needed to make evidence-based decisions on political and moral issues concerning the family.

As depicted in the YouTube video, “Modern Family” (see above) what constitutes a “typical family” in Canada has changed tremendously over the past decades. One of the most notable changes has been the increasing number of mothers who work outside the home. Earlier in Canadian society, most family households consisted of one parent working outside the home and the other being the primary child care provider. Because of traditional gender roles and family structures, this was typically a working father and a stay-at-home mom. Research shows that in 1951 only 24% of all women worked outside the home (Li, 1996). In 2009, 58.3% of all women did, and 64.4% of women with children younger than three years of age were employed (Statistics Canada, 2011).

Sociologists interested in this topic might approach its study from a variety of angles. One might be interested in its impact on a child’s development; another sociologist may explore its effect on family income; while a third sociologist might examine how other social institutions have responded to this shift in society. A sociologist studying the impact of working mothers on a child’s development might ask questions about children raised in child care settings outside the home. How is a child socialized differently when raised largely by a child care provider rather than a parent? Do early experiences in a school-like child care setting lead to improved academic performance later in life? How does a child with two working parents perceive gender roles compared to a child raised with a stay-at-home parent? Another sociologist might be interested in the increase in working mothers from an economic perspective. Why do so many households today have dual incomes? Has this changed the income of families substantially? How do women’s dual roles in the household and in the wider economy affect their occupational achievements and ability to participate on an equal basis with men in the workforce and in society more generally? What impact does the larger economy play in the economic conditions of an individual household? Do people view money — savings, spending, debt — differently than they have in the past (e.g., recall themes highlighted by Nancy Folbre in the video “What is work?”, Module 7).

Curiosity about this trend’s influence on social institutions might lead a researcher to explore its effect on the nation’s educational and child care systems. Has the increase in working mothers shifted traditional family responsibilities onto schools, such as providing lunch and even breakfast for students? How does the creation of after-school care programs shift resources away from traditional school programs? What would the effect be of providing a universal, subsidized child care program on the ability of women to pursue uninterrupted careers? Or how does the shift to dual income earners within households impact the provision of, and more importantly, the division of emotional labour?

As these examples show, sociologists study many real-world topics. Their research often influences social policies and political issues. Results from sociological studies on this topic might play a role in developing federal policies like the Employment Insurance maternity and parental benefits program, or they might bolster the efforts of an advocacy group striving to reduce social stigmas placed on stay-at-home dads, or they might help governments determine how to best allocate funding for education. Many European countries like Sweden have substantial family support policies, such as a full year of parental leave at 80% of wages when a child is born, and heavily subsidized, high-quality daycare and preschool programs. In Canada, a national subsidized daycare program existed briefly in 2005 but was scrapped in 2006 by the Conservative government and replaced with a $100-a-month direct payment to parents for each child. Sociologists might be interested in studying whether the benefits of the Swedish system — in terms of children’s well-being, lower family poverty, and gender equality — outweigh the drawbacks of higher Swedish tax rates.

The family is an excellent example of an institution that can be examined at the micro-, meso-, and macro- levels of analysis. For example, the debate between functionalist and critical sociologists on the rise of non-nuclear family forms is a macro-level debate. It focuses on the family in relationship to a society as a whole. Since the 1950s, the functionalist approach to the family has emphasized the importance of the nuclear family — a cohabiting man and woman who maintain a socially approved sexual relationship and have at least one child — as the basic unit of an orderly and functional society. Although only 39% of families conformed to this model in 2006, in functionalist approaches, it often operates as a model of the ‘normal family’, with the implication that non-normal family forms lead to a variety of society-wide dysfunctions such as crime, drug use, poverty, and welfare dependency .

On the other hand, critical perspectives emphasize the inequalities and power relations within the family and their relationship to inequality in the wider society. The contemporary diversity of family forms does not indicate the “decline of the family” (i.e., of the ideal of the nuclear family) but the diverse responses of the family form to the tensions of gender inequality and historical changes in the economy and society. The typically large, extended family of the rural, agriculture-based economy 100 years ago in Canada was very different from the single breadwinner-led “nuclear” family of the Fordist economy following World War II; it is different again from today’s families who have to respond to economic conditions of precarious employment, fluid modernity, and norms of gender and sexual equality. In the critical perspective, the nuclear family should be thought of less as a normative model for how families should be and more as an historical anomaly that reflected the specific social and economic conditions of the two decades following the Second World War. These are analyses that set out to understand the family within the context of macro-level processes or society as a whole.

At the meso-level, the sociology of mate selection and marital satisfaction reveal the various ways in which the dynamics of the group, or the family form itself, act upon the desire, preferences, and choices of individual actors. At the meso-level, sociologists are concerned with the interactions within groups where multiple social roles interact simultaneously. Since the spontaneity of romantic love and notions of individual “chemistry” have become so central to our concepts of mate selection in Western societies, it is interesting to note the social and group influences that impinge on what otherwise seems a purely individual choice: the appraisal of socially defined “assets” in potential mates, in-group/out-group dynamics in mate preference, and demographic variables that affect the availability of desirable mates (see discussion below). In the age of digital technology and the increased availability/use of online dating apps a sociologist working at the Meso-level of analysis may investigate how these technologies are impacting the dating ‘market’? For example, are online dating apps significantly expanding the pool of potential partners and increasing options for individual choice which may lead to intimate partnerships that are based on greater compatibility between the individuals involved? Alternatively, a sociologist working at the macro level of analysis may be more inclined to examine how the use of online dating apps is indicative of increased penetration of financial markets into the sphere of intimate human relationships

Another area of study at the Meso-level of analysis may involve examination of the life cycle of marriages and family independently of the specific individuals involved. Marital dissatisfaction and divorce peak in the 5th year of marriage and again between the 15th and 20th years of marriage. The presence or absence of children in the home also affects marital satisfaction — nonparents and parents whose children have left home have the highest level of marital satisfaction. Thus, the family form itself appears to have built-in qualities or dynamics regardless of the personalities or specific qualities of family members.

At the micro-level of analysis, sociologists focus on the dynamics between individuals within families. One example, of which probably every married couple is acutely aware, is the interactive dynamic described by exchange theory. Exchange theory proposes that all relationships are based on giving and returning valued “goods” or “services.” Individuals seek to maximize their rewards in their exchanges with others. How do they weigh up who is contributing more, and who is contributing less, of the valuable resources that sustain the marriage relationship (such as money, time, chores, emotional support, romantic gestures, quality time, etc.)? What happens to the family dynamic when one spouse is a net debtor and another a net creditor in the exchange relationship? In The Unbearable Lightness of Being, the Czech novelist Milan Kundera describes the way every relationship forges an implicit contract regarding these exchanges within the first 6 weeks. It is as if a template has been established that will govern the nature of the conflicts, tensions, and disagreements between a married couple for the duration of their relationship. Kundera is writing fiction, but the dynamic he describes exemplifies a micro-level analysis in that this “contract” is a form created through the interaction between specific individuals. Afterwards, it acts as a structure that constrains their interaction. In the more severe cases of unequal exchange, domestic violence, whether physical or emotional, can be the result. The dynamics of “intimate terrorism” and “violent resistance” describe the extreme outcomes of unequal exchange.

Symbolic interactionist theories indicate that families are groups in which participants view themselves as family members and act accordingly. In other words, families are groups in which people come together to form a strong primary group connection, maintaining emotional ties to one another over a long period of time. Such families could potentially include groups of close friends as family. However, the way family groupings view themselves is not independent of the wider social forces and current debates in society at large. The discussion of how the different theoretical perspectives contribute to our understanding of marriage and family in society is elaborated more fully below. Prior to developing that discussion further it is useful to undertake a more detailed examination of the fit between perceptions about marriage and family in society, and what the empirical evidence indicates about the diversity experience within marital and familial relationships.

North Americans are somewhat divided when it comes to determining what does and what does not constitute a family. In a 2010 survey conducted by Ipsos Reid, participants were asked what they believed constituted a family unit. 80% of respondents agreed that a husband, wife, and children constitute a family. 66% stated that a common-law couple with children still constitutes a family. The numbers drop for less traditional structures: a single mother and children (55%), a single father and children (54%), grandparents raising children (50%), common-law or married couples without children (46%), gay male couples with children (45%) (Postmedia News, 2010). This survey revealed that children tend to be the key indicator in establishing “family” status: the percentage of individuals who agreed that unmarried couples constitute a family nearly doubled when children were added.

Another study also revealed that 60% of North Americans agreed that if you consider yourself a family, you are a family (a concept that reinforces an interactionist perspective) (Powell et al., 2010). Canadian statistics are based on the more inclusive definition of “census families.” Statistics Canada defines a census family as “composed of a married or common-law couple, with or without children, or of a lone parent living with at least one child in the same dwelling. Couples can be of the opposite sex or of the same sex” (Statistics Canada, 2012). Census categories aside, sociologists would argue that the general concept of family is more diverse and less structured than in years past. Society has given more leeway to the design of a family — making room for what works for its members (Jayson, 2010).

Family is, indeed, a subjective concept, but it is a fairly objective fact that family (whatever one’s concept of it may be) is very important to North Americans. In a 2010 survey by Pew Research Center in Washington, D.C., 76% of adults surveyed stated that family is “the most important” element of their life — just 1% said it was “not important” (Pew Research Center, 2010). It is also very important to society. American President Ronald Reagan notably stated, “The family has always been the cornerstone of American society. Our families nurture, preserve, and pass on to each succeeding generation the values we share and cherish, values that are the foundation of our freedoms” (Lee, 2009). The dark side of this importance can also be seen in Reagan’s successful use of “family values” rhetoric to attack welfare mothers. His infamous “welfare queen” story about a Black single mother in Chicago, who supposedly defrauded the government of $150,000 in welfare payments, was a complete fabrication that nevertheless “worked” politically because of widespread social anxieties about the decline of the family. While the design of the family may have changed in recent years, the fundamentals of emotional closeness and support are still present. Most respondents to the Pew survey stated that their family today is at least as close (45%) or closer (40%) than the family with which they grew up (Pew Research Center, 2010).

Alongside the debate surrounding what constitutes a family is the question of what North Americans believe constitutes a marriage. Many religious and social conservatives believe that marriage can only exist between man and a woman, citing religious scripture and the basics of human reproduction as support. As Prime Minister Stephen Harper put it, “I have no difficulty with the recognition of civil unions for nontraditional relationships but I believe in law we should protect the traditional definition of marriage” (Globe and Mail, 2010). Social liberals and progressives, on the other hand, believe that marriage can exist between two consenting adults — be they a man and a woman, a woman and a woman, or a man and a man — and that it would be discriminatory to deny such a couple the civil, social, and economic benefits of marriage.

With single parenting and cohabitation (when a couple shares a residence but not a marriage) becoming more acceptable in recent years, people may be less motivated to get married. In a recent survey, 39% of respondents answered “yes” when asked whether marriage is becoming obsolete (Pew Research Center, 2010). The institution of marriage is likely to continue, but some previous patterns of marriage will become outdated as new patterns emerge. In this context, cohabitation contributes to the phenomenon of people getting married for the first time at a later age than was typical in earlier generations (Glezer, 1991). Furthermore, marriage will continue to be delayed as more people place education and career ahead of “settling down.”

North Americans typically equate marriage with monogamy, when someone is married to only one person at a time. In many countries and cultures around the world, however, having one spouse is not the only form of marriage. In a majority of cultures (78%), polygamy, or being married to more than one person at a time, is accepted (Murdock, 1967), with most polygamous societies existing in northern Africa and East Asia (Altman and Ginat, 1996). Instances of polygamy are almost exclusively in the form of polygyny. Polygyny refers to a man being married to more than one woman at the same time. The reverse, when a woman is married to more than one man at the same time, is called polyandry. It is far less common and only occurs in about 1% of the world’s cultures (Altman and Ginat, 1996). The reasons for the overwhelming prevalence of polygamous societies are varied but they often include issues of population growth, religious ideologies, and social status.

While the majority of societies accept polygyny, the majority of people do not practise it. Often fewer than 10% (and no more than 25 to 35%) of men in polygamous cultures have more than one wife; these husbands are often older, wealthy, high-status men (Altman and Ginat, 1996). The average plural marriage involves no more than three wives. Negev Bedouin men in Israel, for example, typically have two wives, although it is acceptable to have up to four (Griver, 2008). As urbanization increases in these cultures, polygamy is likely to decrease as a result of greater access to mass media, technology, and education (Altman and Ginat, 1996).

In Canada, polygamy is considered by most to be socially unacceptable and it is illegal. The act of entering into marriage while still married to another person is referred to as bigamy and is prohibited by Section 290 of the Criminal Code of Canada (Minister of Justice, 2014). Polygamy in Canada is often associated with those of the Mormon faith, although in 1890 the Mormon Church officially renounced polygamy. Fundamentalist Mormons, such as those in the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (FLDS), on the other hand, still hold tightly to the historic Mormon beliefs and practices and allow polygamy in their sect.

The prevalence of polygamy among Mormons is often overestimated due to sensational media stories such as the prosecution of polygamous sect leaders in Bountiful, B.C., the Yearning for Zion ranch raid in Texas in 2008, and popular television shows such as HBO’s Big Love and TLC’s Sister Wives. It is estimated that there are about 37,500 fundamentalist Mormons involved in polygamy in the United States, Canada, and Mexico, but that number has shown a steady decrease in the last 100 years (Useem, 2007).

North American Muslims, however, are an emerging group with an estimated 20,000 practicing polygamy. Again, polygamy among North American Muslims is uncommon and occurs only in approximately 1% of the population (Useem, 2007). For now, polygamy among North American Muslims has gone fairly unnoticed by mainstream society, but like fundamentalist Mormons whose practices were off the public’s radar for decades, they may someday find themselves at the centre of social debate.

When considering their lineage, most Canadians look to both their father’s and mother’s sides. Both paternal and maternal ancestors are considered part of one’s family. This pattern of tracing kinship is called bilateral descent. Note that kinship, or one’s traceable ancestry, can be based on blood, marriage, or adoption. 60% of societies, mostly modernized nations, follow a bilateral descent pattern. Unilateral descent (the tracing of kinship through one parent only) is practised in the other 40% of the world’s societies, with high concentration in pastoral cultures (O’Neal, 2006).

There are three types of unilateral descent: patrilineal, which follows the father’s line only; matrilineal, which follows the mother’s side only; and ambilineal, which follows either the father’s only or the mother’s side only, depending on the situation. In partrilineal societies, such as those in rural China and India, only males carry on the family surname. This gives males the prestige of permanent family membership while females are seen as only temporary members (Harrell, 2001). North American society assumes some aspects of partrilineal decent. For instance, most children assume their father’s last name even if the mother retains her birth name.

In matrilineal societies, inheritance and family ties are traced to women. Matrilineal descent is common in Native American societies, notably the Crow and Cherokee tribes. In these societies, children are seen as belonging to the women and, therefore, one’s kinship is traced to one’s mother, grandmother, great grandmother, and so on (Mails, 1996). In ambilineal societies, which are most common in Southeast Asian countries, parents may choose to associate their children with the kinship of either the mother or the father. This choice may be based on the desire to follow stronger or more prestigious kinship lines or on cultural customs, such as men following their father’s side and women following their mother’s side (Lambert, 2009).

Tracing one’s line of descent to one parent rather than the other can be relevant to the issue of residence. In many cultures, newly married couples move in with, or near to, family members. In a patrilocal residence system it is customary for the wife to live with (or near) her husband’s blood relatives (or family of orientation). Patrilocal systems can be traced back thousands of years. In a DNA analysis of 4,600-year-old bones found in Germany, scientists found indicators of patrilocal living arrangements (Haak et al. 2008). Patrilocal residence is thought to be disadvantageous to women because it makes them outsiders in the home and community; it also keeps them disconnected from their own blood relatives. In China, where patrilocal and patrilineal customs are common, the written symbols for maternal grandmother (wáipá) are separately translated to mean “outsider” and “women” (Cohen, 2011).

Similarly, in matrilocal residence systems, where it is customary for the husband to live with his wife’s blood relatives (or her family of orientation), the husband can feel disconnected and can be labelled as an outsider. The Minangkabau people, a matrilocal society that is indigenous to the highlands of West Sumatra in Indonesia, believe that home is the place of women and they give men little power in issues relating to the home or family (Joseph and Najmabadi, 2003). Most societies that use patrilocal and patrilineal systems are patriarchal, but very few societies that use matrilocal and matrilineal systems are matriarchal, as family life is often considered an important part of the culture for women, regardless of their power relative to men.

9.2 Variations in Family Life: Historically and within Individual Families

Whether you grew up watching the Cleavers, the Waltons, the Huxtables, or the Simpsons, most of the iconic families you saw in television sitcoms included a father, a mother, and children cavorting under the same roof while comedy ensued. The 1960s was the height of the suburban American nuclear family on television with shows such as The Donna Reed Show and Father Knows Best. While some shows of this era portrayed single parents (My Three Sons and Bonanza, for instance), the single status almost always resulted from being widowed, not divorced or unwed.

Although family dynamics in real North American homes were changing, the expectations for families portrayed on television were not. North America’s first reality show, An American Family (which aired on PBS in 1973) chronicled Bill and Pat Loud and their children as a “typical” American family. Cameras documented the typical coming and going of daily family life in true cinéma-vérité style. During the series, the oldest son, Lance, announced to the family that he was gay, and at the series’ conclusion, Bill and Pat decided to divorce. Although the Loud’s union was among the 30% of marriages that ended in divorce in 1973, the family was featured on the cover of the March 12 issue of Newsweek with the title “The Broken Family” (Ruoff, 2002).

Less traditional family structures in sitcoms gained popularity in the 1980s with shows such as Diff’rent Strokes (a widowed man with two adopted African American sons) and One Day at a Time (a divorced woman with two teenage daughters). Still, traditional families such as those in Family Ties and The Cosby Show dominated the ratings. The late 1980s and the 1990s saw the introduction of the dysfunctional family. Shows such as Roseanne, Married with Children, and The Simpsons portrayed traditional nuclear families, but in a much less flattering light than those from the 1960s did (Museum of Broadcast Communications, 2011).

Over the past 10 years, the nontraditional family has become somewhat of a tradition in television. While most situation comedies focus on single men and women without children, those that do portray families often stray from the classic structure: they include unmarried and divorced parents, adopted children, gay couples, and multigenerational households. Even those that do feature traditional family structures may show less traditional characters in supporting roles, such as the brothers in the highly rated shows Everybody Loves Raymond and Two and Half Men. Even wildly popular children’s programs as Disney’s Hannah Montana and The Suite Life of Zack & Cody feature single parents.

In 2009, ABC premiered an intensely nontraditional family with the broadcast of Modern Family. The show follows an extended family that includes a divorced and remarried father with one stepchild, and his biological adult children — one of who is in a traditional two-parent household, and the other who is a gay man in a committed relationship raising an adopted daughter. While this dynamic may be more complicated than the typical “modern” family, its elements may resonate with many of today’s viewers. “The families on the shows aren’t as idealistic, but they remain relatable,” states television critic Maureen Ryan. “The most successful shows, comedies especially, have families that you can look at and see parts of your family in them” (Respers France, 2010).

As we have established, the concept and reality of family has changed greatly over time. Historically, it was often thought that most (certainly many) families evolved through a series of predictable stages. Developmental or “stage” theories used to play a prominent role in family sociology (Strong and DeVault, 1992). Today, however, these models have been criticized for their linear and conventional assumptions as well as for their failure to capture the diversity of family forms. While reviewing some of these once-popular theories, it is important to identify their strengths and weaknesses.

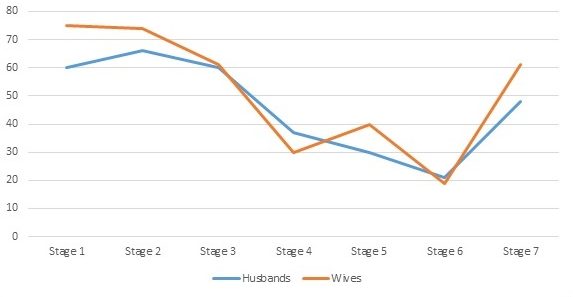

The set of predictable steps and patterns families experience over time is referred to as the family life cycle. One of the first designs of the family life cycle was developed by Paul Glick in 1955. In Glick’s original design, he asserted that most people will grow up, establish families, rear and launch their children, experience an “empty nest” period, and come to the end of their lives. This cycle will then continue with each subsequent generation (Glick, 1989). Glick’s colleague, Evelyn Duvall, elaborated on the family life cycle by developing these classic stages of family (Strong and DeVault, 1992):

| Stage | Family Type | Children |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marriage Family | Childless |

| 2 | Procreation Family | Children ages 0 to 2.5 |

| 3 | Preschooler Family | Children ages 2.5 to 6 |

| 4 | School-age Family | Children ages 6–13 |

| 5 | Teenage Family | Children ages 13–20 |

| 6 | Launching Family | Children begin to leave home |

| 7 | Empty Nest Family | “Empty nest”; adult children have left home |

The family life cycle was used to explain the different processes that occur in families over time. Sociologists view each stage as having its own structure with different challenges, achievements, and accomplishments that transition the family from one stage to the next. The problems and challenges that a family experiences in Stage 1 as a married couple with no children are likely very different than those experienced in Stage 5 as a married couple with teenagers. Marital satisfaction of husbands and wives, for example, tends to be high at the beginning of the marriage and remain so into the procreation stage (children ages 0-2.5), falls as children age and reaches its lowest point when the children are teenagers, and then increases again when the children reach adulthood and leave home (Lupri and Frideres, 1981). The most maritally satisfied couples are those who do not have children and those whose children have left home (“empty nesters”), which is ironic considering people often get married to have children (Murphy and Staples, 1979). Some interpret this pattern as meaning simply that between couples “illusions disappear and disenchantment ensues,” whereas the developmental approach of family stages suggests “that meanings couples attached to their relationship and their roles change over time and thus affect marital satisfaction” (Lupri and Frideres, 1981). The success of a family can be measured by how well they adapt to these challenges and transition into each stage.

As early “stage” theories have been criticized for generalizing family life and not accounting for differences in gender, ethnicity, culture, and lifestyle, less rigid models of the family life cycle have been developed. One example is the family life course, which recognizes the events that occur in the lives of families but views them as parting terms of a fluid course rather than in consecutive stages (Strong and DeVault, 1992). This type of model accounts for changes in family development, such as the fact that today, childbearing does not always occur with marriage. It also sheds light on other shifts in the way family life is practised. Society’s modern understanding of family rejects rigid “stage” theories and is more accepting of new, fluid models. In fact contemporary family life has not escaped the phenomenon that Zygmunt Bauman calls fluid (or liquid) modernity, a condition of constant mobility and change in relationships (2000).

The combination of husband, wife, and children that 80% of Canadians believes constitutes a family is not representative of the majority of Canadian families. According to 2011 census data, only 31.9% of all census families consisted of a married couple with children, down from 37.4% in 2001. 63% of children under age 14 live in a household with two married parents. This is a decrease from almost 70% in 1981 (Statistics Canada, 2012). As we noted above, this two-parent family structure is known as a nuclear family, referring to married parents and children as the nucleus, or core, of the group. Recent years have seen a rise in variations of the nuclear family with the parents not being married. The proportion of children aged 14 and under who live with two unmarried cohabiting parents increased from 12.8% in 2001 to 16.3% in 2011 (Statistics Canada, 2012).

Single-parent households are also on the rise. In 2011, 19.3% of children aged 14 and under lived with a single parent only, up slightly from 18% in 2001. Of that 19.3% , 82% live with their mother (Statistics Canada, 2012).

Stepparents are an additional family element in two-parent homes. A stepfamily is defined as “a couple family in which at least one child is the biological or adopted child of only one married spouse or common-law partner and whose birth or adoption preceded the current relationship” (Statistics Canada, 2012). Among children living in two parent households, 10% live with a biological or adoptive parent and a stepparent (Statistics Canada, 2012).

In some family structures a parent is not present at all. In 2010, 106,000 children (1.8% of all children) lived with a guardian who was neither their biological nor adoptive parent. Of these children, 28% lived with grandparents, 44% lived with other relatives, and 28% lived with non-relatives or foster parents. If we also include families in which both parents and grandparents are present (about 4.8% of all census families with children under the age of 14 years), this family structure is referred to as the extended family, and may include aunts, uncles, and cousins living in the same home. Foster children account for about 0.5% of all children in private households.

In the United States, the practice of grandparents acting as parents, whether alone or in combination with the child’s parent, is becoming more common (about 9%) among American families (De Toledo and Brown, 1995). A grandparent functioning as the primary care provider often results from parental drug abuse, incarceration, or abandonment. Events like these can render the parent incapable of caring for his or her child. However, in Canada, census evidence indicates that the percentage of children in these “skip-generation” families remained more or less unchanged between 2001 and 2011 at 0.5% (Statistics Canada, 2012).

Changes in the traditional family structure raise questions about how such societal shifts affect children. Research, mostly from American sources, has shown that children living in homes with both parents grow up with more financial and educational advantages than children who are raised in single-parent homes (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). The Canadian data is not so clear. It is true that children growing up in single-parent families experience a lower economic standard of living than families with two parents. In 2008, female lone-parent households earned an average of $42,300 per year, male lone-parent households earned $60,400 per year, and two-parent families earned $100,200 per year (Williams, 2010). However, in the lowest 20% of families with children aged four to five years old, single-parent families made up 48.9% of households while intact or blended households made up 51.1% (based on 1998/99 data). Single-parent families do not make up a larger percentage of low-income families (Human Resources Development Canada, 2003). Moreover, both the income (Williams, 2010) and the educational attainment (Human Resources Development Canada, 2003) of single mothers in Canada has been increasing, which in turn is linked to higher levels of life satisfaction.

In research published from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (a long-term study initiated in 1994 that is following the development of a large cohort of children from birth to the age of 25), the evidence is ambiguous as to whether having single or dual parents has a significant effect on child development outcomes. For example, indicators of vocabulary ability of children aged four to five years old did not differ significantly between single- and dual-parent families. However, aggressive behaviour (reported by parents) in both girls and boys aged four to five years old was greater in single-parent families (Human Resources Development Canada, 2003). In fact, significant markers of poor developmental attainment were more related to the sex of the child (more pronounced in boys), maternal depression, low maternal education, maternal immigrant status, and low family income (To, et al., 2004). We will have to wait for more research to be published from the latest cycle of the National Longitudinal Survey to see whether there is more conclusive evidence concerning the relative advantages of dual- and single-parent family settings.

Nevertheless, what the data show is that the key factors in children’s quality of life are the educational levels and economic condition of the family, not whether children’s parents are married, common-law, or single. For example, young children in low-income families are more likely to have vocabulary problems, and young children in higher-income families have more opportunities to participate in recreational activities (Human Resources Development Canada, 2003). This is a matter related more to public policy decisions concerning the level of financial support and care services (like public child care) provided to families than different family structures per se. In Sweden, where the government provides generous paid parental leave after the birth of a child, free health care, temporary paid parental leave for parents with sick children, high-quality subsidized daycare, and substantial direct child-benefit payments for each child, indicators of child well-being (literacy, levels of child poverty, rates of suicide, etc.) score very high regardless of the difference between single- and dual-parent family structures (Houseknecht and Sastry, 1996).

Living together before or in lieu of marriage is a growing option for many couples. Cohabitation, when a man and woman live together in a sexual relationship without being married, was practised by an estimated 1.6 million people (16.7% of all census families) in 2011, which shows an increase of 13.9% since 2006 (Statistics Canada, 2012). This surge in cohabitation is likely due to the decrease in social stigma pertaining to the practice. In Quebec in particular, researchers have noted that it is common for married couples under the age of 50 to describe themselves in terms used more in cohabiting relationships than marriage: mon conjoint (partner) or mon chum (intimate friend) rather than mon mari (my husband) (Le Bourdais and Juby, 2002). In fact, cohabitation or common-law marriage is much more prevalent in Quebec (31.5% of census families) and the Northern Territories (from 25.1% in Yukon to 32.7% in Nunavut) than in the rest of the country (13% in British Columbia, for example) (Statistics Canada, 2012).

Cohabitating couples may choose to live together in an effort to spend more time together or to save money on living costs. Many couples view cohabitation as a “trial run” for marriage. Today, approximately 28% of men and women cohabitated before their first marriage. By comparison, 18% of men and 23% of women married without ever cohabitating (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). The vast majority of cohabitating relationships eventually result in marriage; only 15% of men and women cohabitate only and do not marry. About one-half of cohabitators transition into marriage within three years (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

While couples may use this time to “work out the kinks” of a relationship before they wed, the most recent research has found that cohabitation has little effect on the success of a marriage. Those who do not cohabitate before marriage have slightly better rates of remaining married for more than 10 years (Jayson, 2010). Cohabitation may contribute to the increase in the number of men and women who delay marriage. The average age of first marriage has been steadily increasing. In 2008, the average age of first marriage was 29.6 for women and 31 for men, compared to 23 for women and 25 for men through most of the 1960s and 1970s (Milan, 2013).

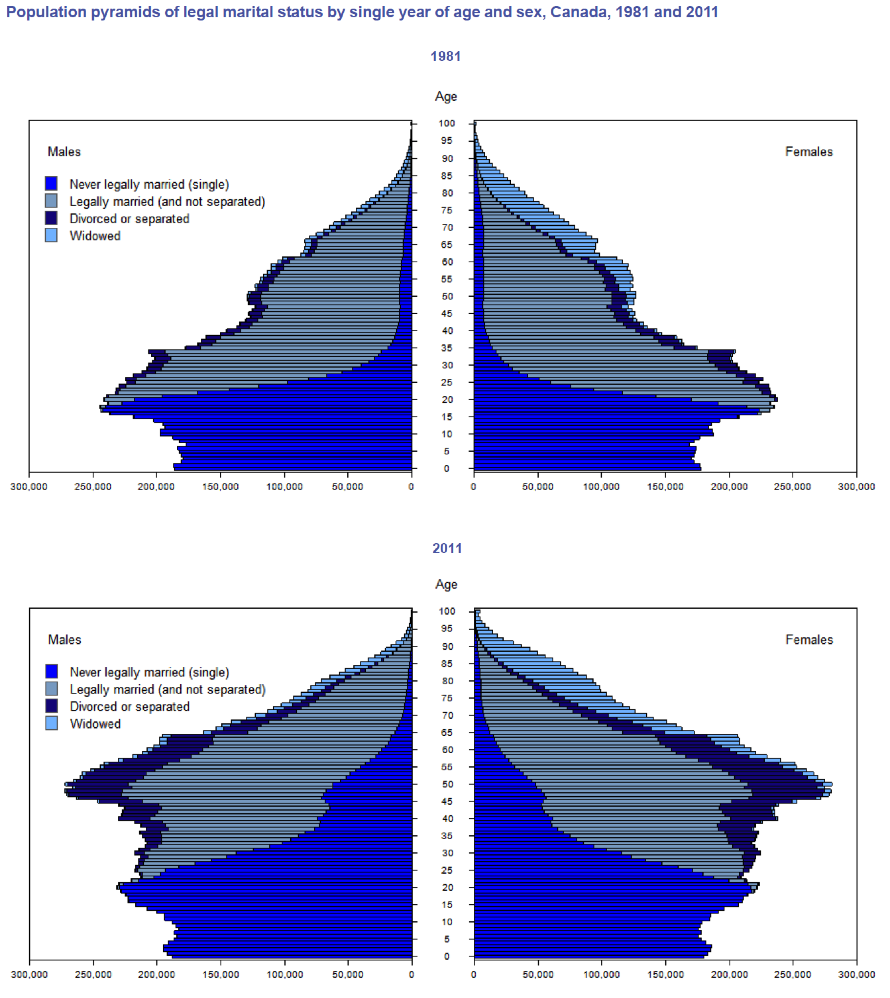

The number of same-sex couples has grown significantly in the past decade. The Civil Marriage Act (Bill C-38) legalized same sex marriage in Canada on July 20, 2005. Some provinces and territories had already adopted legal same-sex marriage, beginning with Ontario in June 2003. In 2011, Statistics Canada reported 64,575 same-sex couple households in Canada, up by 42% from 2006. Of these, about three in ten were same-sex married couples compared to 16.5% in 2006 (Statistics Canada, 2012). These increases are a result of more coupling, the change in the marriage laws, growing social acceptance of homosexuality, and a subsequent increase in willingness to report it.

In Canada, same-sex couples make up 0.8% of all couples. Unlike in the United States where the distribution of same-sex couples nationwide is very uneven, ranging from as low as 0.29% in Wyoming to 4.01% in the District of Columbia (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011), the distribution of same-sex couples in Canada by province or territory is similar to that of opposite-sex couples. However, same-sex couples are more highly concentrated in big cities. In 2011, 45.6% of all same-sex sex couples lived in Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal, compared to 33.4% of opposite-sex couples (Statistics Canada, 2012). In terms of demographics, Canadian same-sex couples tended to be younger than opposite-sex couples. 25% of individuals in same-sex couples were under the age of 35 compared to 17.5% of individuals in opposite-sex couples. There were more male-male couples (54.5%) than female-female couples (Milan, 2013). Additionally, 9.4% of same-sex couples were raising children, 80% of whom were female-female couples (Statistics Canada, 2012).

While there is some concern from socially conservative groups (especially in the United States) regarding the well-being of children who grow up in same-sex households, research reports that same-sex parents are as effective as opposite-sex parents. In an analysis of 81 parenting studies, sociologists found no quantifiable data to support the notion that opposite-sex parenting is any better than same-sex parenting. Children of lesbian couples, however, were shown to have slightly lower rates of behavioural problems and higher rates of self-esteem (Biblarz and Stacey, 2010).

Gay or straight, a new option for many Canadians is simply to stay single. In 2011, about one-fifth of all individuals over the age of 15 did not live in a couple or family (Statistics Canada, 2012). Never-married individuals accounted for 73.1% of young adults in the 25 to 29 age bracket, up from 26% in 1981 (Milan, 2013). More young men in this age bracket are single than young women — 78.8% to 67.4% — reflecting the tendency for men to marry at an older age and to marry women younger than themselves (Milan, 2013).

Although both single men and single women report social pressure to get married, women are subject to greater scrutiny. Single women are often portrayed as unhappy “spinsters” or “old maids” who cannot find a man to marry them. Single men, on the other hand, are typically portrayed as lifetime bachelors who cannot settle down or simply “have not found the right girl.” Single women report feeling insecure and displaced in their families when their single status is disparaged (Roberts, 2007). However, single women older than 35 report feeling secure and happy with their unmarried status, as many women in this category have found success in their education and careers. In general, women feel more independent and more prepared to live a large portion of their adult lives without a spouse or domestic partner than they did in the 1960s (Roberts, 2007).

The decision to marry or not to marry can be based a variety of factors including religion and cultural expectations. Asian individuals are the most likely to marry while Black North Americans are the least likely to marry (Venugopal, 2011). Additionally, individuals who place no value on religion are more likely to be unmarried than those who place a high value on religion. For Black women, however, the importance of religion made no difference in marital status (Bakalar, 2010). In general, being single is not a rejection of marriage; rather, it is a lifestyle that does not necessarily include marriage. By age 40, according to census figures, 20% of women and 14% of men will have never married (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011).

It was noted above that having children is perceived to be a primary factor in being assigned the status of being a family in North America. Interestingly, however, there is a growing proportion of women, men and couples who are creating a life without children. Whether this is a situation of resulting from a conscious decision not to have children, or a result of the inability to have children, the individuals involved tend to confront similar pressures and reactions as a result of societal expectations.

Male or female, growing older means confronting the psychological issues that come with entering the last phase of life. Young people moving into adulthood take on new roles and responsibilities as their lives expand, but an opposite arc can be observed in old age. What are the hallmarks of social and psychological change and how are these changes related to changes in marital and familial relationships?

Retirement — the idea that one may stop working at a certain age — is a relatively recent idea. Up until the late 19th century, people worked about 60 hours a week and did so until they were physically incapable of continuing. In 1889, Germany was the first country to introduce a social insurance program that provided relief from poverty for seniors. At the request of the German chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, the German emperor wrote to the German parliament: “those who are disabled from work by age and invalidity have a well-grounded claim to care from the state” (U.S. Social Security Administration, N.d.). The retirement age was initially set at age 70. In Canada, early Labour MPs (a precursor to the CCF and then the NDP) agreed to support the minority Liberal government, elected in 1925, in exchange for the introduction of the first Old Age Pensions Act (1927). In 1951 the Old Age Security Act was passed, creating the contemporary Old Age Security system, and in 1966 the Canada Pension Plan and Quebec Pension Plan were introduced. These plans continued to provide benefits to seniors at age 70, but by 1971 age 65 had been gradually phased in (Canadian Museum of History, N.d.).

In the 21st century, most people hope that at some point they will be able to stop working and enjoy the fruits of their labour. But do people look forward to this time or do they fear it? When people retire from familiar work routines, some easily seek new hobbies, interests, and forms of recreation. Many find new groups and explore new activities, but others may find it more difficult to adapt to new routines and loss of social roles, losing their sense of self-worth in the process. This is also a point in time within a longstanding marital relationship that individuals may need to become re-acquainted with spending significant amounts of time with one another in the absence of other distractions such as paid work and/or child care. It is also a phase in the marital relationship where there is increased potential for changes in the health status on one or both members of the relationship, and eventually the death of a partner.

Each phase of life has challenges that come with the potential for fear. Erik H. Erikson (1902–1994), in his view of socialization, broke the typical life span into eight phases. Each phase presents a particular challenge that must be overcome. In the final stage, old age, the challenge is to embrace integrity over despair. Some people are unable to successfully overcome the challenge. They may have to confront regrets, such as being disappointed in their children’s lives or perhaps their own. They may have to accept that they will never reach certain career goals. Or they must come to terms with what their career success has cost them, such as time with their family or declining personal health. Others, however, are able to achieve a strong sense of integrity, embracing the new phase in life. When that happens, there is tremendous potential for creativity. They can learn new skills, practise new activities, and peacefully prepare for the end of life.

For some, overcoming despair might entail remarriage after the death of a spouse. A study conducted by Kate Davidson (2002) reviewed demographic data that asserted men were more likely to remarry after the death of a spouse, and suggested that widows (the surviving female spouse of a deceased male partner) and widowers (the surviving male spouse of a deceased female partner) experience their postmarital lives differently. Many surviving women enjoyed a new sense of freedom, as many were living alone for the first time. On the other hand, for surviving men, there was a greater sense of having lost something, as they were now deprived of a constant source of care as well as the focus on their emotional life.

It is no secret that Canadians are squeamish about the subject of sex. When the subject is the sexuality of elderly people no one wants to think about it or even talk about it. That fact is part of what makes the 1971 cult classic movie, Harold and Maude, so provocative. In this cult favourite film, Harold, an alienated, young man, meets and falls in love with Maude, a 79-year-old woman. What is so telling about the film is the reaction of his family, priest, and psychologist, who exhibit disgust and horror at such a match.

Although it is difficult to have an open, public national dialogue about aging and sexuality, the reality is that our sexual selves do not disappear after age 65. People continue to enjoy sex — and not always safe sex — well into their later years. In fact, some research suggests that as many as one in five new cases of AIDS occur in adults over 65 (Hillman, 2011).

In some ways, old age may be a time to enjoy sex more, not less. For women, the elder years can bring a sense of relief as the fear of an unwanted pregnancy is removed and the children are grown and taking care of themselves. However, while we have expanded the number of psycho-pharmaceuticals to address sexual dysfunction in men, it was not until very recently that the medical field acknowledged the existence of female sexual dysfunctions (Bryant, 2004).

How do different groups in our society experience the aging process? Are there any experiences that are universal, or do different populations have different experiences? An emerging field of study looks at how lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (LGBT) people experience the aging process and how their experience differs from that of other groups or the dominant group. This issue is expanding with the aging of the baby boom generation; not only will aging boomers represent a huge bump in the general elderly population, but the number of LGBT seniors is expected to double by 2030 (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011).

A recent study titled The Aging and Health Report: Disparities and Resilience among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Older Adults finds that LGBT older adults have higher rates of disability and depression than their heterosexual peers. They are also less likely to have a support system that might provide elder care: a partner and supportive children (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011). Even for those LGBT seniors who are partnered, in the United States some states do not recognize a legal relationship between two people of the same sex, reducing their legal protection and financial options. In Canada, Supreme Court decisions in 2003 and the Civil Marriage Act in 2005 legalized same sex marriage.

As they transition to assisted-living facilities, LGBT people have the added burden of “disclosure management:” the way they share their sexual and relationship identity. In one case study, a 78-year-old lesbian lived alone in a long-term care facility. She had been in a long-term relationship of 32 years and had been visibly active in the gay community earlier in her life. However, in the long-term care setting, she was much quieter about her sexual orientation. She “selectively disclosed” her sexual identity, feeling safer with anonymity and silence (Jenkins et al., 2010). A study from the National Senior Citizens Law Center reports that only 22% of LGBT older adults expect they could be open about their sexual orientation or gender identity in a long-term care facility. Even more telling is the finding that only 16% of non-LGBT older adults expected that LGBT people could be open with facility staff (National Senior Citizens Law Center, 2011).

Same-sex marriage can have major implications for the way the LGBT community ages. With marriage comes the legal and financial protection afforded to opposite-sex couples, as well as less fear of exposure and a reduction in the need to “retreat to the closet” (Jenkins et al., 2010).

For most of human history, the standard of living was significantly lower than it is now. Humans struggled to survive with few amenities and very limited medical technology. The risk of death due to disease or accident was high in any life stage, and life expectancy was low. As people began to live longer, death became associated with old age.

For many teenagers and young adults, losing a grandparent or another older relative can be the first loss of a loved one they experience. It may be their first encounter with grief, a psychological, emotional, and social response to the feelings of loss that accompanies death or a similar event.

People tend to perceive death, their own and that of others, based on the values of their culture. While some may look upon death as the natural conclusion to a long, fruitful life, others may find the prospect of dying frightening to contemplate. People tend to have strong resistance to the idea of their own death, and strong emotional reactions of loss to the death of loved ones. Viewing death as a loss, as opposed to a natural or tranquil transition, is often considered normal in North America.

What may be surprising is how few studies were conducted on death and dying prior to the 1960s. Death and dying were fields that had received little attention until psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross began observing people who were in the process of dying. As Kübler-Ross witnessed people’s transition toward death, she found some common threads in their experiences. She observed that the process had five distinct stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. She published her findings in a 1969 book called On Death and Dying. The book remains a classic on the topic today.

Kübler-Ross found that a person’s first reaction to the prospect of dying is denial, characterized by not wanting to believe that he or she is dying, with common thoughts such as “I feel fine” or “This is not really happening to me.” The second stage is anger, when loss of life is seen as unfair and unjust. A person then resorts to the third stage, bargaining: trying to negotiate with a higher power to postpone the inevitable by reforming or changing the way he or she lives. The fourth stage, psychological depression, allows for resignation as the situation begins to seem hopeless. In the final stage, a person adjusts to the idea of death and reaches acceptance. At this point, the person can face death honestly, regarding it as a natural and inevitable part of life, and can make the most of their remaining time.

The work of Kübler-Ross was eye-opening when it was introduced. It broke new ground and opened the doors for sociologists, social workers, health practitioners, and therapists to study death and help those who were facing death. Kübler-Ross’s work is generally considered a major contribution to thanatology: the systematic study of death and dying.

Of special interests to thanatologists is the concept of “dying with dignity.” Modern medicine includes advanced medical technology that may prolong life without a parallel improvement to the quality of life one may have. In some cases, people may not want to continue living when they are in constant pain and no longer enjoying life. Should patients have the right to choose to die with dignity? Dr. Jack Kevorkian was a staunch advocate for physician-assisted suicide: the voluntary or physician-assisted use of lethal medication provided by a medical doctor to end one’s life. Physician-assisted suicide is slightly different from euthanasia, which refers to the act of taking someone’s life to alleviate that person’s suffering, but that does not necessarily reflect the person’s expressed desire to commit suicide.

In Canada, physician-assisted suicide is illegal, although suicide itself has not been illegal since 1972. On moral and legal grounds, advocates of physician-assisted suicide argue that the law unduly deprives individuals of their autonomy and right to freely choose to end their own life with assistance; that existing palliative care can be inadequate to alleviate pain and suffering; that the law discriminates against disabled people who are unable, unlike able-bodied people, to commit suicide by themselves; and that assisted suicide is taking place already in an informal way, but without proper regulations. Those opposed argue that life is a fundamental value and killing is intrinsically wrong, that legal physician-assisted suicide could result in abuses with respect to the most vulnerable members of society, that individuals might seek assisted suicide for financial reasons or because services are inadequate, and that it might reduce the urgency to find means of improving the care of people who are dying (Butler, Tiedemann, Nicol, and Valiquet, 2013).

The controversy surrounding death with dignity laws is emblematic of the way our society tries to separate itself from death. Health institutions have built facilities to comfortably house those who are terminally ill. This is seen as a compassionate act, helping relieve the surviving family members of the burden of caring for the dying relative. But studies almost universally show that people prefer to die in their own homes (Lloyd, White, and Sutton, 2011). Is it our social responsibility to care for elderly relatives up until their death? How do we balance the responsibility for caring for an elderly relative with our other responsibilities and obligations? As our society grows older, and as new medical technology can prolong life even further, the answers to these questions will develop and change.

The changing concept of hospice is an indicator of our society’s changing view of death. Hospice is a type of health care that treats terminally ill people when cure-oriented treatments are no longer an option (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, N.d.). Hospice doctors, nurses, and therapists receive special training in the care of the dying. The focus is not on getting better or curing the illness, but on passing out of this life in comfort and peace. Hospice centres exist as places where people can go to die in comfort, and increasingly, hospice services encourage at-home care so that someone has the comfort of dying in a familiar environment, surrounded by family (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, N.d.). While many of us would probably prefer to avoid thinking of the end of our lives, it may be possible to take comfort in the idea that when we do approach death in a hospice setting, it is in a familiar, relatively controlled place.

9.3 Challenges Families Face

9.3.1 Divorce and Remarriage

As the structure of family changes over time, so do the challenges families face. Events like divorce and remarriage present new difficulties for families and individuals. Other long-standing domestic issues, such as abuse, continue to strain the health and stability of families.

Divorce, while fairly common and accepted in modern Canadian society, was once a word that would only be whispered and was accompanied by gestures of disapproval. Prior to the introduction of the Divorce Act in 1968 there was no federal divorce law in Canada. In provincial jurisdictions where there were divorce laws, spouses had to prove adultery or cruelty in court. The 1968 Divorce Act broadened the grounds for divorce to include mental and physical cruelty, desertion, and/or separation for more than three years, and imprisonment. In 1986, the Act was amended again to make “breakdown of marriage” the sole ground for divorce. Couples could divorce after one year’s separation, and there was no longer a requirement to prove “fault” by either spouse.

These legislative changes had immediate consequences on the divorce rate. In 1961, divorce was generally uncommon, affecting only 36 out of every 100,000 married persons. In 1969, the year after the introduction of the Divorce Act, the number of divorces doubled from 55 divorces per 100,000 population to 124. The divorce rate peaked in 1987, after the 1986 amendment, at 362 divorces per 100,000 population. Over the last quarter century divorce rates have dropped steadily, reaching 221 divorces per 100,000 population in 2005 (Kelly, 2010). The dramatic increase in divorce rates after the 1960s has been associated with the liberalization of divorce laws (as noted above); the shift in societal makeup, including the increase of women entering the workforce (Michael, 1978); and marital breakdowns in the large cohort of baby boomers (Kelly, 2010). The decrease in divorce rates can be attributed to two probable factors: an increase in the age at which people get married, and an increased level of education among those who marry — both of which have been found to promote greater marital stability.

| Province or Territory | 1961 | 1968 | 1969 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 36.0 | 54.8 | 124.2 | 238.9 | 298.8 | 362.3 | 282.3 | 262.2 | 231.2 | 220.7 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1.3 | 3.0 | 20.0 | 96.6 | 118.8 | 193.7 | 175.5 | 170.6 | 169.9 | 153.5 |

| Prince Edward Island | 7.6 | 18.2 | 91.9 | 166.3 | 154.5 | 213.1 | 214.4 | 191.0 | 197.0 | 204.8 |

| Nova Scotia | 33.2 | 64.8 | 102.1 | 263.3 | 292.4 | 307.8 | 265.1 | 244.6 | 218.2 | 209.5 |

| New Brunswick | 32.4 | 22.9 | 55.3 | 187.3 | 237.6 | 273.1 | 228.7 | 191.6 | 227.3 | 192.2 |

| Québec | 6.6 | 10.2 | 49.2 | 236.4 | 282.5 | 324.7 | 291.6 | 274.5 | 231.2 | 203.0 |

| Ontario | 43.9 | 69.3 | 160.4 | 223.4 | 290.7 | 403.7 | 280.2 | 264.4 | 223.8 | 229.4 |

| Manitoba | 33.9 | 47.9 | 136.3 | 213.3 | 272.6 | 356.5 | 252.4 | 235.3 | 212.0 | 206.9 |

| Saskatchewan | 27.1 | 40.0 | 92.1 | 187.3 | 240.0 | 286.4 | 233.9 | 228.4 | 214.7 | 194.1 |

| Alberta | 78.0 | 125.7 | 221.0 | 336.0 | 391.8 | 390.2 | 332.1 | 276.6 | 271.7 | 246.4 |

| British Columbia | 85.8 | 110.8 | 205.0 | 278.6 | 374.1 | 397.6 | 296.1 | 275.0 | 246.8 | 233.8 |

| Yukon | 164.1 | 200.0 | 262.5 | 389.9 | 379.6 | 546.6 | 289.0 | 371.9 | 222.4 | 350.2 |

| Northwest Territories | 36.7 | 96.8 | 130.8 | 171.6 | 195.8 | 115.0 | 142.8 | 229.8 | 152.5 | |

| Nunavut | Nunavut is included in the Northwest Territories before 2000. | 25.5 | 33.3 | |||||||

So what causes divorce? While more young people are choosing to postpone or opt out of marriage, those who enter into the union do so with the expectation that it will last. A great deal of marital problems can be related to stress, especially financial stress. According to researchers participating in the University of Virginia’s National Marriage Project, couples who enter marriage without a strong asset base (like a home, savings, and a retirement plan) are 70% more likely to be divorced after three years than are couples with at least $10,000 in assets. This is connected to factors such as age and education level that correlate with low incomes.

The addition of children to a marriage creates added financial and emotional stress. Research has established that marriages enter their most stressful phase upon the birth of the first child (Popenoe and Whitehead, 2001). This is particularly true for couples who have multiples (twins, triplets, and so on). Married couples with twins or triplets are 17% more likely to divorce than those with children from single births (McKay, 2010). Another contributor to the likelihood of divorce is a general decline in marital satisfaction over time. As people get older, they may find that their values and life goals no longer match up with those of their spouse (Popenoe and Whitehead, 2004).

Divorce is thought to have a cyclical pattern. Children of divorced parents are 40% more likely to divorce than children of married parents. And when we consider children whose parents divorced and then remarried, the likelihood of their own divorce rises to 91% (Wolfinger, 2005). This might result from being socialized to a mindset that a broken marriage can be replaced rather than repaired (Wolfinger, 2005). That sentiment is also reflected in the finding that when both partners of a married couple have been previously divorced, their marriage is 90% more likely to end in divorce (Wolfinger, 2005).

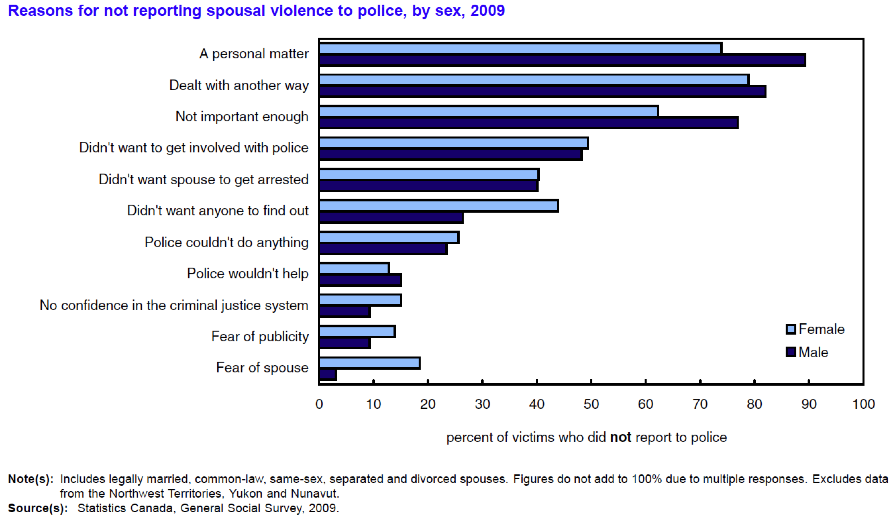

Samuel Johnson is quoted as saying that getting married a second time was “the triumph of hope over experience.” In fact, according to the 2001 Statistics Canada General Social Survey, 43% of individuals whose first marriage failed married again, while 16% married again after the death of their spouse. Another 1% of the ever-married population (people who have been married but may not currently be married), aged 25 and over, had been married more than twice (Clark and Crompton, 2006). American data show that most men and women remarry within five years of a divorce, with the median length for men (three years) being lower than for women (4.4 years). This length of time has been fairly consistent since the 1950s. The majority of those who remarry are between the ages of 25 and 44 (Kreider, 2006).