27 How to use Telehealth to Enhance Care in Isolated Northern Practices

Michael Jong

Aim: To learn how to use telehealth to enhance access to care in northern practices

Methods: A description of how telehealth can be implemented and what it can used for.

Results: Telehealth allows for care where the capacity to provide the service is not available locally. It benefits clients through allowing for treatment closer to home and local health providers through expedient advice from consultants at a distant site. Telehealth has the potential to save lives and reduce costs to the healthcare system. Training on the use of telehealth and proper equipment setup is necessary to make telehealth effective.

Conclusions: Telehealth is a useful system that support both patients and health staff in isolated northern practices

Key Terms: Telehealth, Northern practices

Introduction

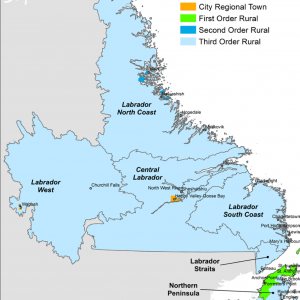

There are many health care challenges for Canadians, but few are any greater than the challenge of providing care for those who live in northern, remote, and sparsely populated regions of this country. Despite much higher health care expenditures per capita in the three northern Territories compared to the Canadian average, the population health outcomes in the North continue to lag far behind that of the South (Young & Chatwood, 2011). Health expenditures are increasing across the country, but the increases are most pronounced in the territories (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2015). The challenges of provision of health care is compounded by a shortage and high turnover of health professionals in the North (Cameron, 2011). One of the potential solutions for the high expenditures is to improve efficiency in access to care through telehealth (Mendez, Jong, Keays-White & Turner, 2013). Telehealth can support the work of northern nurses and other health care providers, reduce the stress of working in remote locations, and potentially improve recruitment and retention of health professionals, including but not limited to nurses (Jong, 2013). This chapter describes the services currently provided via telehealth in central Labrador and Labrador North Coast (see Figure 1), the impact of having the services delivered by telehealth, and the recommendations on how to implement telehealth in northern communities.

Figure 1 – Map of Labrador. The population in the largest community (Happy Valley-Goose Bay) in this region is 6,400. It is the administrative center and referral health center for Labrador. The smallest community has 150 residents and the total catchment population of the health center is 11,500. Telehealth is operational all the time as part of an essential health service in all our communities.

What Can Be Provided Via Telehealth

Our experience in Labrador shows there is a high acceptance of care via telehealth for both clients and nurses. When a physician consult is required for chronic disease management, telehealth can provide more timely care that is not impeded via the vagaries of travel by visiting providers to the remote communities. Other services provided in northern Labrador via telehealth are:

- Preoperative assessments and postoperative care, so that clients travel to the hospital only once for surgery.

- Simple fractures and dislocation care remotely.

- Assistance with procedures and surgeries via more experienced colleagues.

- Daily remote hemodialysis rounds.

- Teleoncology

- Point of care ultrasound with the aid of a local person and led remotely via video by an experienced health provider.

- Diagnoses and management of fractures and dislocations, intraocular eye injuries, heart failure, pericardial effusion, pneumothorax, pneumonia, pulmonary edema/ARDS, pleural effusion, intraperitoneal fluid/bleed, cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, renal stones, urinary retention, intra uterine and ectopic pregnancies.

- Mental health assessment and psychotherapy.

- Leading resuscitation remotely via video.

What Are the Potential Impacts?

Telehealth enables access to care closer to home. A 14-month study on robotic telepresence in a remote community in Labrador by Jong (2013) showed that the requirement for transportation of clients out to a referral center was reduced by 40%, which more than offset the cost of the telehealth system. All the nurses and physicians reported that they were satisfied with the system. Telehealth eased stress, especially with urgent/emergent cases. It improved job satisfaction and shared care. During 50% of consultations via telehealth, nurses reported learning something new. Clients expressed a high degree of comfort with consultations via telehealth. They and were more accepting of referrals for medical consultation via telehealth knowing that they do not have to leave the community for the service.

Over the past ten years, resuscitations in northern Labrador are routinely lead by Emergency Room (ER) physicians through telehealth. An average of two successful resuscitations per year are made possible through stat (immediate) videoresuscitation (Jong, 2010). Physicians are able to stabilize clients until the medevac team can fly into the communities. Critically ill clients are successfully managed via telehealth in remote communities for several days when inclement weather prevents air travel. Through telehealth, management of a client in the emergency room in a remote community is similar to that of a client in one of the trauma bays in the ER. In short, telehealth has a great potential to provide better access to care especially for remote communities in circumpolar regions where distances to referral centers are great and cost high.

How to Make It Happen

Telehealth equipment must be easily accessible if it is going to be used. Impediments to use include the amount of time needed to set up the telehealth consult. For videoresuscitation, urgent and immediate accessibility is crucial. In the facilities in Labrador, videoconference units are permanently stationed at a room at the center of the emergency department at the referral center. Stat calls from remote nursing stations are triaged the same way as any other clients who show up in the emergency room. Mobile videoconference units are positioned in the emergency rooms of all nursing stations. The units in the remote sites are on a mobile base with rollers so they can be moved around for use elsewhere. This maximizes the use of the units for other non-urgent consultations.

IT Infrastructure

The minimum bandwidth requirement for video transmission is 256 kbps. Video transmission can also be run through 3-G or faster cellular networks. A secure intranet can be used for telehealth. The other way to ensure security is by using the encryption provided with the telehealth software. Encryption will allow for private access via public Wi-Fi and cellular networks anywhere in the world.

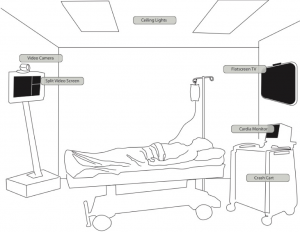

A split screen on the videoconference units allows for visualization of the image at both sites. Ideally, the split screen can be altered so that the bigger image is of the distant site and the smaller image is of the local site (see Figure 1). At the site with the client, a full screen of the distant command center is ideally the image on the screen so all participants can easily see the consultant.

The videoconference unit needs a video camera that can be controlled at a remote site. The camera needs the ability to zoom and to rotate 180 degrees sideways and 45 degrees up and 45 degrees down. The ability for presets is ideal and preferably it is controlled by the remote site. The best presets are usually the full view of the room, the cardiac monitor, and close-up of the client’s upper torso. Autofocus in the camera is another useful feature.

The videoconference units need a good audio conference system. It is useful for the consultant situated in a noisy department, such as the emergency room, to have a remote headset to reduce distractions caused by the background noise. The background noise can be also reduced if the door to the room is closed. In Labrador, it has been our experience that inquisitive staff in an emergency department may pop in and start chatting before realizing the distraction to the team at the remote site.

Room Setup for Video Resuscitation

The best view of the resuscitation effort is from an oblique view at the end of the bed. The video camera sits on top of the video units ideally at about 7-8 feet high so the camera can see the person managing the airway at the end of the bed and the person doing chest compressions from the opposite side of the bed where the videoconference unit is located. The height of the camera allows for the leader at the distant command center to see from an above angle. It reduces the reflection from overhead lights in the room. The video screen needs to be high enough for the resuscitation team members to see the team leader.

Moreover, the videoconference unit in the remote resuscitation site needs to be far away enough from the team so that everyone involved can see the team leader. The unit is usually at one corner of the room. The bed and monitors are at the diagonally opposite corner of the room. The monitors are ideally located at head height at the end of the bed so they will be less likely to be obstructed by the remote team members.

Figure 2 – Telehealth Videoresuscitation Room setup. This figure shows the video unit (video camera on top of video screen) at one corner of the room, the bed and monitors at the diagonally opposite corner of the room, and the monitors located at head height at the end of the bed (Jong, 2010, p. 522).

Training

Training in the running of a code using simulation and video is strongly recommended. Besides allowing the team to practice resuscitation, it helps to organize the layout of the room and the setup of the videoconference unit. It is very important for the team leader at the distant site to learn to control the remote camera, which is in essence the remote eye. With practice, it is possible to unconsciously and competently control the remote camera to move seamlessly from the views of room, client, and monitors. The remote team leader has most of the necessary information without asking the remote team members who are already fully occupied with the resuscitation effort. The remote lead is able to see the vitals on the cardiac monitor, check the drip rate on the IV pump, provide feedback on the quality of CPR, summarize for the team, provide clear directions, and receive constructive feedback.

The quickest way to focus upon and capture an item of interest in the remote site is to first zoom out completely, place the item, e.g., cardiac monitor, in the middle of the screen, and then zoom in until the item occupies the full screen.

The consultant or lead at the referral center needs to be cognizant of the view seen by the remote team. If the intention is to offer eye contact, there is a need to look at the camera which is usually at the top of the computer screen. For most video consults, it is best to place the client’s face on the top of the screen so that the client perceives that eye contact is made when looking at the face. It is also better to have the face and chest view of the health provider for most consults. Consultants or leads should avoid showing the table and notes that they are taking simultaneously, so the scribbling of the notes does not distract the client. To maintain a respectful interaction, it is best for the remote health provider not to look down but to have the camera at eye level.

It is often easier to show a health provider at a distant site what to use and how to use it on the video than to describe it. For example, it is easier to show in the video screen the setup for an improvised flutter valve for needle chest decompression using a large bore IV cannula and a finger of a glove than to describe it.

Conclusion

Telehealth is a valuable tool especially in remote practice where there are limited human and technical supports. It provides clients’ access to care closer to home and supports for northern nurses and others in difficult emergent situations. For telehealth to be successful, proper setup and training are required.

Additional Resources

Bradford NK, Caffery LJ, Smith AC. Telehealth services in rural and remote Australia: a systematic review of models of care and factors influencing success and sustainability. Rural Remote Health [Internet]. 2016 Oct-Dec;16(4):4268. Epub 2016 Nov 6. PubMed PMID: 27817199.

Nunavut telehealth project impact evaluation report. Montreal (QC): Infotelmed Communications Inc; 2003 Sep 26

References

Cameron, E. (2011). State of the Knowledge: Inuit Public Health, 2011. Prince George, BC: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2015). National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975 to 2015. Retrieved from http://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/nhex_trends_narrative_report_2015_en.pdf.

Jong, M. (2010). Resuscitation by video in northern communities. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 69(5), 519-527. doi:10.3402/ijch.v69i5.17686

Jong, M. (2013). Impact of robotic telemedicine in a remote community in Canada. In L. Van Gemert-Pijnen and H. C. Ossebaard (Eds.), Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on eHealth, Telemedicine, and Social Medicine (pp. 168-171). Nice, France: International Academy, Research, and Industry Association.

Mendez, I., Jong, M., Keays-White, D., & Turner, G. (2013). The use of remote presence for health care delivery in a northern Inuit community: A feasibility study. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 72(1), 21112. doi:10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21112

Young, T. K., & Chatwood, S. (2011). Health care in the north: What Canada can learn from its circumpolar neighbours. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 183(2), 209-214. doi:10.1503/cmaj.100948