Chapter 3 Designing a Course That Integrates the Sustainable Development Goals

Designing a Course That Integrates the Sustainable Development Goals

What Are the Sustainable Development Goals?

This section is adapted from “What Are the SDGs?” in Embedding Sustainable Development Goals in Teaching and Learning by Aditi Garg, published by the University of Saskatchewan in 2023.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) address complex and interlinked social and environmental challenges. They came into effect on January 1, 2016, following a historic United Nations Summit in September 2015. The SDGs are a call to action for all countries to mobilize efforts to end poverty, fight inequalities, and tackle climate change, while ensuring that no one is left behind.

The 17 SDGs also fit within the 5P Framework—People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnership. The planetprovides a place for people to live in prosperity through partnership and peace. This relationship and interdependence is evident in the “wedding cake” model from the Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University. Partnerships are needed throughout the three levels (economy, society, biosphere) to advance the goals.

For each of the 17 goals, there is a list of specific targets we aim to reach. For a more detailed list of all 169 targets, visit GlobalGoals.org.

In the previous chapter, we talked about how meeting the “interlinked social, economic and environmental challenges captured by the SDGs” has been identified by the University of Saskatchewan (USask) as being consistent with the university’s commitment to be “The University the World Needs” (see the University Plan 2025). In subsequent chapters, you will see several examples of how USask instructors have integrated the SDGs into their courses.

Often when instructors set out to integrate changes into their courses (including changes related to institutional, college, or department priorities), they will have many questions:

- Why should I do this?

- Why should I do it this way?

- How can I do this?

- What will this look like for students? What will it look like for me as the instructor?

- What resources will I need?

This chapter tries to answer these and other “why,” “how,” and “what” questions related to designing courses that integrate the SDGs. At the end of the chapter, we provide links to additional resources related to the concepts covered here.

Before you dive into the course design information, please note the following:

|

Why?

Why Integrate the SDGs Into Your Course(s)

If you’re reading this book, you may already be interested in integrating the SDGs into your course(s). If you’re not convinced, or you need help convincing your colleagues to support this change, here are several reasons you should integrate the SDGs into your course(s):

- The SDGs address some of the major problems facing the world today—climate change, inequality in education and economic conditions, food insecurity, and political polarization. (See the table of competencies for sustainability in Chapter 2.)

- Students care about these issues, so including them in your course(s) will increase student engagement and empower them, two things that will benefit their wellness and improve the teaching and learning experience for both you and them.

- The problems addressed by the SDGs are happening now and are in the news every day. Tying coursework to current events keeps content fresh, increases student engagement, and may reduce incidents of academic misconduct (it is harder to plagiarize information about a current event compared to an older text that has been cited extensively). This enriches learning for the student and the educator.

Why Students Should Take Your Course(s)

This is an important question to ask before you start to design your course(s). Consider how each course fits into a larger program or complements other courses the students may take. How will students use what they learn from you in other courses, in their careers, in their communities, and in their lives overall? Your answers will help shape the course’s learning outcomes, assessments, and teaching strategies.

Why You Should Use a Course Design Process

An intentional course design process, such as the one at USask, is essential for several reasons.

A process like this ensures the course structure and content are carefully thought out and align with the desired learning outcomes. This alignment enhances the overall learning experience for students, making the course more engaging, relevant, and effective.

Additionally, an intentional course design process supports student wellness by incorporating strategies that promote a positive and supportive learning environment. When instructors consider diverse learning styles, incorporate inclusive teaching practices, and foster a sense of belonging, students are more likely to thrive academically and personally.

For instructors, an intentional course design process provides a framework for effective teaching. It helps them organize and structure their course materials, activities, and assessments to maximize student learning while minimizing workload. Instructors can streamline their teaching practices and create a balanced workload by incorporating evidence-based instructional strategies and leveraging technology appropriately. This, in turn, supports instructors’ wellness by reducing stress and enabling them to focus on meaningful engagement with students.

Supporting student and instructor wellness. The information and ideas in this book are meant to help instructors incorporate sustainability into their courses without creating insurmountable work for themselves. The framework will also help instructors integrate the SDGs with a wellness factor. The “why, how, what” course design process described below is intended to support student wellness and academic success while also supporting instructor wellness.

Why is student wellness crucial for achieving academic success and preparing students for their desired post-university success? Student wellness plays a pivotal role in both academic and post-university success. Integrating student wellness into course design and prioritizing it throughout university creates an environment that supports academic achievement and personal growth and sets the stage for students’ future success.

Mental and physical well-being significantly impacts students’ cognitive abilities, motivation, and overall engagement in their studies. When students feel supported, emotionally balanced, and healthy, they are more likely to effectively manage stress, concentrate on their studies, and actively participate in the learning process.

Students who develop healthy habits and self-care practices during their university years are better equipped to navigate challenges, manage work-life balance, and sustain well-being beyond university. By fostering wellness, universities prepare students academically and equip them with the skills and mindset necessary to thrive personally and professionally beyond academia.

Building relationships. Being intentional about building relationships in course design is of utmost importance as it fosters a sense of connection, trust, and engagement between instructors and students.

When educators invest time in understanding their students’ needs and interests while designing the course, they can tailor the content to be more relevant and meaningful. This intentional approach enhances the learning experience and encourages students to actively participate, seek guidance, and collaborate with their peers.

Strong relationships in the learning environment create a safe space for students to share their thoughts and concerns, ultimately leading to better academic performance and overall well-being.

How?

In this section, you will find instructions, ideas, and examples to help you integrate the SDGs into your course(s). We will look at some of the practical work needed to design an engaging and effective course that integrates the SDGs. The main areas that we will explore are:

- Constructive alignment

- Learning outcomes

- Assessments

- Teaching strategies

How to Use Constructive Alignment

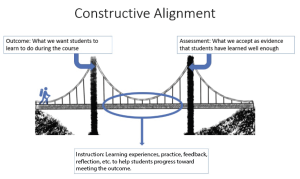

Constructive alignment is a principle used to design your courses so that the learning outcomes, assessments, and teaching strategies align. The planning process begins with the desired learning outcomes, then considers the ways students can demonstrate that they have achieved those outcomes (assessments). Once you have defined these two elements, you can develop teaching strategies (activities) that will give students the knowledge and experience they need to progress toward the stated outcomes and successfully complete the course.

The video “Constructive Alignment,” from the Gwenna Moss Centre’s YouTube channel (GMCTL USask), explains the concept in greater detail.

The figure below shows the course as a bridge—imagine a student preparing to walk across it. For the learner to successfully cross the bridge, from the start of the course until they use what they learn in the course, there needs to be alignment. The instructor designs the bridge before the course commences, assuring an aligned and structurally sound journey, given known variables. Using sustainability as a consistent element or theme in your course can help lay the deck of the bridge for a more navigable crossing. In the following sections, we will provide more information about writing defined outcomes and selecting assessments and teaching strategies.

How to Write Learning Outcomes

Learning outcomes are the first component of constructive alignment. They describe the knowledge and skills you want students to be able to demonstrate by the end of the course. Often instructors begin their course design with the topics they want to cover, but when you start by defining the learning outcomes, you shift the focus from the instructor to the learner.

Effective learning outcomes have three parts:

- Performance: “By the end of the course, students should be able to …”

- Condition: The condition, circumstance, or environment in which student learning will occur or be demonstrated (e.g., in a classroom or lab, on a project or exam, given specific equipment or resources)

- Criteria: The type, quantity, quality/standard, accuracy, degree, completion time

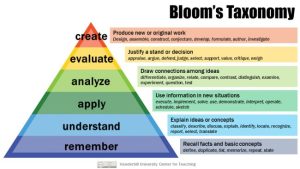

You might choose learning outcomes that use “action words” (or verbs) coordinating with one or more of the levels in Bloom’s Taxonomy, a hierarchical classification system that categorizes learning objectives by level of complexity. Draw on higher-order cognitive tasks (create/evaluate), which align with higher-impact instructional approaches.While assessment and instructional approaches are discrete from the outcome, as part of conductive alignment you will likely want to pause and consider what evidence you will have that students are learning and what strategies you will use to get there. Use an assignment guide to align purpose, task, criteria for assessment, and other inclusive priorities. We also recommend that you review other USask principles of assessment and strategies when drafting outcomes during course design.

How to Align Learning Outcomes With the SDGs

This section is adapted from “Writing Learning Outcomes With the SDGs” in Embedding Sustainable Development Goals in Teaching and Learning by Aditi Garg, published by the University of Saskatchewan in 2023.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has already written learning objectives for the SDGs. However, you may wish to align these more closely with your own course or program outcomes.

For example:

| Original math learning outcome: Support a position or decision relevant to self, family, or community by analyzing statistical data, as well as considering other facts. (Math Foundations 20, Saskatchewan). |

| + |

| SDGs learning outcome: Learners will be able to communicate about issues of health, including sexual and reproductive health… and prevention strategies. (Goal 3, Good Health and Well-being) |

| = |

| SDG + math outcome: Learners will be able to support a position regarding health to community by analyzing and communicating statistical data. |

How to Develop Assessments

Assessments measure student progress in achieving the learning outcomes. Simply tracking student attendance doesn’t measure student progress toward outcomes.

What you assess and the type of assessment you use should directly align with the learning outcomes. For example, suppose a course outcome is that students will be able to explain how water insecurity affects the ability of girls in remote regions of Guatemala to attend school. A multiple-choice quiz may not be the best way to measure progress on that outcome, as the responses will likely lack nuance. A presentation, debate, or paper is likely a better measure of student progress. For example, a Collaborative Online International Learning experience partnered with university students in Guatemala, in which students prepare a presentation, would likely yield a rich learning experience.

Summative and formative assessments. Summative assessments, given at the end of a course with no feedback or opportunity for improvement, are what most people think of when they think about assessment. When students complete a traditional summative assessment, they usually receive a grade with minimal feedback, so the stakes are higher than other types of assessment where feedback and more opportunities to improve exist. Thus, summative assessments should come after opportunities to learn and improve through practice and feedback.

There are many types of summative assessments to choose from. The following is not a complete list, but it should give you some ideas. You can find additional ideas in the resources listed at the end of this chapter.

|

|

In some cases, depending on the discipline, class size, and learning outcomes, some of these may be consideredauthentic assessments (more on this in the next section). Also, many of these can be done by students individually or in groups.

Formative assessments are opportunities for you and your students to determine how well the learning process is going and for students to practise and learn in a low-stakes environment. For example, having students submit a draft version of a paper to receive feedback from the instructor, teaching assistant, or a fellow student with no grade attached allows them to learn from the process and apply that learning to a final version (a summative assessment) that will be graded. Other types of formative assessment and feedback include using a student response system (a tool that allows students to respond to instructor questions through a handheld or mobile device), practice quizzes, or practice lab activities.

In each of these cases, students can receive feedback, and instructors can see where students may be struggling while providing opportunities for practice and learning.

Authentic assessments and open pedagogy. Authentic assessments provide students with opportunities to apply what they learn in a context that is similar to the ways they will use their learning when they are no longer students in the course. A student taking a course in political studies may later need to write a memorandum or speech, but they are unlikely to need to write an essay. An undergraduate student in chemistry is likely going to need to know how to use a laboratory safely, but they are less likely to need to be able to take a multiple-choice quiz.

Taking an open pedagogy approach to assessment allows students to contribute to creating knowledge and resources that demonstrate their learning. Open pedagogy involves students creating or modifying existing Open Educational Resources such as textbooks, but also creating materials like websites, posters, or even print materials that can be used by future students and community members. This approach increases engagement and may help address instructor concerns related to academic integrity.

Open pedagogy also provides opportunities for students to show how their discipline and their learning can contribute to helping local communities and the world address the sustainability challenges we face today.

Student choice. Something you may want to consider is giving students some choice when it comes to assessments. Giving students choices can help to increase engagement and decrease stress.

Choice in assessment can take on a variety of formats. Following are just a few possibilities for assessments that can be related to the SDGs:

- The instructor chooses the format (e.g., an essay or presentation), but the students can choose which of the SDGs they’ll address for that assessment.

- The instructor gives learners the option of completing the assessment in one of two formats, such as writing a paper or creating a podcast with a partner.

- The instructor provides students with a rubric for an assessment aligned with the outcomes, but the students get to choose the format for their assessment. In this case, one student may write a paper, while another may create an interactive digital artifact that others can use later. The emphasis is on the outcome, not the format of the assessment.

How to Choose Teaching Strategies

Once you have your learning outcomes and your aligned assessments, you must choose teaching strategies that also align with these. There is a wide range of learning activities that can be used within your teaching, including lectures, fieldwork, discussions, collaborations, and so on.

Whatever strategies you choose, they must

- align with outcomes and assessment,

- fit in the context of the course, and

- be appropriate for the learners in the course.

Your teaching strategies should help students reach the outcomes and show evidence of their learning through the assessments.

Ideally, the teaching strategies will prepare students for not only the assessments but also application beyond the classroom. Just as learners benefit from authentic assessments (see above), authentic teaching strategies help learners transfer and apply what they learn in a course to the workplace, community, and future learning (formal or informal). While it may be tempting to spend all of your class time lecturing, consider integrating other teaching strategies to engage students and help them retain and use what they are learning.

Give students opportunities to practise applying the skills and knowledge they are learning in the course. As discussed in the section on formative assessment above, students should be able to practise in a low-stakes environment where practice activities do not involve grades. Sometimes instructors might need to help learners see the value of completing these activities in the context of their overall learning, and also show how the content and activities can address current issues the students are concerned about, such as climate change. Doing so, and giving consistent and relevant feedback throughout the term, can lead to an increase in student engagement in the course.

What?

The “What” part of course design is where the “Why” and “How” parts come together to provide both instructors and students with a clear picture of each class and where the teaching and learning happen.

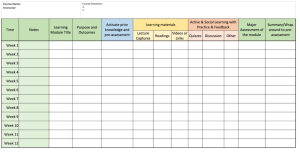

What to Include in Your Blueprint

Once you have your learning outcomes, your assessments, and your teaching strategies, you need to pull them all together into a cohesive and coherent plan, or blueprint, that makes sense to you. Much like a blueprint for a house, the course blueprint shows all of the details and how they come together to create the whole.

Creating a blueprint for your course will allow you to see if

- gaps exist in your plan that need to be corrected,

- the order of activities and assessments is appropriate or needs to be adjusted, and

- you’re spending an appropriate amount of time on each learning outcome.

The blueprint will also include the learning materials you’ll need to prepare for each class meeting and the information you’ll need to include in your course syllabus.

Here is an example of a course blueprint.

What Learning Materials to Choose

It is important to choose appropriate technologies for use in your course. You will also need to choose which textbooks and other learning materials you will use. When doing so, please remember the following:

- Choose materials that align with your learning outcomes.

- Choose materials that are accessible to students. Consider things like cost, the ability for adaptive technologies to work with the material, and so on.

- If you need to order textbooks from the bookstore, do so well in advance.

- Consider choosing an open textbook or other Open Educational Resources that are free and can be adapted to meet local needs, including integrating material on the SDGs.

What to Include in Your Syllabus

Your course syllabus serves several purposes. While the university considers it a contract, learners use it as a guide to help them navigate the course. It contains information on assessments and due dates, but it also provides insight into what the learning experience will be like in the course.

Your syllabus will set the tone for the rest of the term. The tone is influenced by what you include in your syllabus, whether you use welcoming or punitive language, and the design decisions you’ve made for the course.

The Syllabus page on the USask Teaching and Learning website provides valuable information on syllabus requirements from the USask Academic Courses Policy and about the USask Syllabus Generator. The web page includes links to a Syllabus Template as a Microsoft Word document and a PDF version of the Syllabus Creation Guide.

Reflection and Feedback

Reflection and feedback are vital in course design as they enable continuous improvement and student-centred learning. Through reflection, instructors assess their teaching methods and identify areas for enhancement. By seeking and incorporating student feedback, professors gain insights into individual needs and adapt the course accordingly. This iterative process ensures the course remains relevant and engaging, fostering a positive and impactful learning experience.

USask’s Student Learning Experience Questionnaire (SLEQ) is a validated instrument to learn about students’ perceptions of their learning experiences. The survey is somewhat customizable, which enables instructors to use SLEQ as formative feedback about their courses that can inform and assess course design change.

Suggested Resources

Assessments

Biem, R. (2022, October 24). Assessing outcomes versus grading assignments. Educatus.https://sites.usask.ca/gmcte/2022/10/24/assessing-outcomes-versus-grading-assignments/

Biem, R. (2023, January 16). Defining competencies and outcomes. Educatus. https://sites.usask.ca/gmcte/2023/01/16/4478/

Gwenna Moss Centre for Teaching and Learning. (2023, March 1). USask assessment principles. Educatus. https://sites.usask.ca/gmcte/2023/03/01/usask-assessment-principles/

University of Saskatchewan Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Learning technologies. Retrieved December 5, 2023, from https://teaching.usask.ca/strategies/lt-illustrative-examples.php

Open Educational Practices

University of Saskatchewan Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Open Educational Practices. Retrieved December 5, 2023, from https://teaching.usask.ca/curriculum/open-educational-practices.php

Sustainability

Garg, A. (2023, April). Embedding Sustainable Development Goals in teaching and learning. University of Saskatchewan. https://openpress.usask.ca/sdgs/

Institute for Sustainability, Energy, and Environment (iSEE). (n.d.). Classroom tools: Prepared sustainability resources. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved December 5, 2023, from https://sustainability.illinois.edu/education/teaching/tools/

OER Commons. (n.d.). Climate education. Retrieved December 5, 2023, from https://oercommons.org/hubs/climate

Teaching Strategies

Centre for Higher Education Research, Policy and Practice. (2019). Active learning strategies for higher education. Technological University Dublin. https://arrow.tudublin.ie/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=cherrpbook

Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning. (2020). Teaching and learning activities. In Course design program (pp. 46–52). University of Calgary. https://taylorinstitute.ucalgary.ca/sites/default/files/Content/Resources/Course-Design/22-TAY-Course-Design-Workshop-Manual.pdf

Universal Design for Learning

Dzaman, S., Fenlon, D., Maier, J., & Marchione, T. (2022). Universal design for learning: One small step. University of Saskatchewan. https://openpress.usask.ca/universaldesignforlearning/