Chapter 6 Teaching Sustainability in Kinesiology

Teaching Sustainability in Kinesiology

Shannon Forrester

My Why

I was born and raised on the beautiful land in Treaty 6 Territory and the Homeland of the Métis. The land nurtured and shaped me to become the person I am today, igniting my love of physical activity and, in turn, my passion for kinesiology. I have a deeply rooted respect for the land and its profound effect on me. I recognize the reciprocal relationship with this land that existed for people long before me and my settler ancestors. I cherish the thought that it will continue to nurture my children and future generations, and I am invested in its protection.

I didn’t always embrace sustainability. My strong connection to nature and being “green” initially led me to view sustainability through a purely environmental lens. As such, when I first learned about the Sustainability Faculty Fellows (SFF) program at the University of Saskatchewan (USask), I dismissed thoughts of involvement. Although I do what I can to support a healthy environment, I did not see a strong fit professionally. Sure, I could support surface-level environmental strategies like promoting the use of stairs, active transport, or online distribution and submission of classroom materials; however, I did not consider this directly relevant to my area of teaching.

Looking a little deeper, I discovered that the SFF program used the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals(SDGs; see Chapter 3) as a framework to understand sustainability not just through an environmental lens but through a social and economic one. When I considered sustainability within all three dimensions, I quickly realized sustainability in teaching and learning was a great fit for me and the College of Kinesiology.

Conceptualizing sustainability through the SDGs, I could envision both personal and professional connections, tying my love of nature (SDG 15: Life on Land and SDG 13: Climate Action) with my love of physical activity and movement (SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being). I also strongly believe in social justice, so I was particularly interested in the strong intersection with equity, diversity, and inclusion, as well as Indigenization. I felt that sustainability in teaching and learning would support not only my personal ambitions, but also the strategic goals of my college.

Another draw to sustainability in teaching and learning was pedagogical. Foundational concepts of sustainable teaching include reflection, relationships, and effective communication, which align strongly with my teaching philosophy. More specifically, these were teaching strategies that would enhance student learning and focus on the development of competencies for sustainability (see Chapter 2)—which I believed in, which I already tried to foster, and which would extend beyond the classroom to develop positive global citizens.

I saw that the SFF program could help me make my contribution to the type of world in which I wanted to live, work, and play. My ability to make a difference is twofold:

- By using powerful Open Educational Practices, I can create opportunities for my students to reflect, share, and act in ways that support the SDGs and help them develop key competencies.

- I can increase awareness and advocacy by supporting colleagues and other educators in using sustainability in teaching and learning.

What I Did in My Course

My first step was to review the USask sustainability strategy, Critical Path to Sustainability, which commits to capitalizing on strengths. The mission statement for the College of Kinesiology is “We lead and inspire movement, health, and performance,” which aligns with SDG Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and would be a significant strength.

The Canadian Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals addresses the 17 SDGs and adds key Canadian targets:

- Adoption of healthy behaviours for all Canadians

- Ensuring Canadians experience healthy and satisfying lives

- Prevention of premature death in Canada

Extending these ambitions for all Canadians aligns with our teaching and research in the College of Kinesiology—Indigenous wellness, healthy aging and management of chronic conditions, child and youth health and development, and human performance (College of Kinesiology, 2018).

Given this alignment, I would argue that all College of Kinesiology courses support sustainability, even if our current complement of courses does not explicitly make this connection for students. The course in which I chose to embed sustainability, intentionally and explicitly, was KIN 424 – Physical Activity and Aging. This is a fourth-year course focused on topics related to physical activity among older adults.

My intention was not to completely overhaul the course,[1] but rather to maintain the primary focus while incorporating sustainability. To accomplish this, I started with a blueprint tool to determine where my current practice and strategies already aligned with the SDGs and sustainable student competencies. Throughout, I was guided by three principles for sustainability in teaching and learning at USask:

- Course outcomes that focus on development of sustainability competencies

- Instructional strategies that provide agency to students to reflect, share, act

- Assessment that directly measures student skill level in competencies

Merging these with principles of constructive alignment (Biggs, 1996), I started to revamp the course.

Learning Outcomes

My next step was to identify the learning outcomes I wanted students to achieve and then update learning activities and assessments to align with the revised outcomes. From a discipline perspective, I knew I wanted students’ respectful perspective taking to reflect on the ways kinesiology could support the SDGs. More specifically, I wanted students to identify the personal and professional role they would play in enhancing their own health and wellness as well as that of their communities and the planet; however, the learning outcomes for the course would have to be specific and aligned to the curriculum.

I had to draw explicit connections between the existing course outcomes and sustainability. Although my course content could speak to a variety of SDGs, and my intention was to draw on all of them, I wanted the sustainability-themed outcomes to be more targeted.

The two SDGs I identified as having the strongest affiliation with the course content were SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). Using Embedding Sustainability Development Goals in Teaching and Learning as a guide, I was able to embed these SDGs in my learning outcomes.

| KIN 424 – Physical Activity and Again Course Outcomes

Course Learning Outcomes:

|

Teaching Practices

With a working set of revised learning outcomes, I next turned my attention to my teaching practices. Would they facilitate achievement of both my learning outcomes and the new sustainable competencies? In other words, was I providing for student choice and voice? Was I working toward changing mind, heart, and skill sets? Designing reflective practice? Leveraging interdisciplinary efforts? Was I making community connections? (See principles for sustainability in teaching and learning at USask.)

Once I felt I had adequately planned for the use of these strategies to support the competencies, I moved on to leveraging Open Educational Practices. Although open education appears to have fluid definitions (Cronin, 2017; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2020), the aspects of “open” that spoke to me for supporting sustainability included

- accessibility through creation and use of Open Educational Resources,

- student agency,

- authentic assessment, and

- community engagement.

Although I was able to address development of all student competencies, I was selective in my emphasis. Throughout the course, I wanted students to become proficient in sustainability through UNESCO’s Reflect, Share, Act model. To “act,” the students would work in their community to promote SDG Goal 3. Consequently, I focused on the sustainability competencies that were most relevant.

Learning Activities

Building a foundation for sustainability began on the first day of class with a welcome, a land acknowledgment, and perusal of the syllabus. The land acknowledgment was the perfect opportunity to introduce the concept of sustainability and position sustainability within USask as outlined in the University Plan 2025. It also provided an opportunity to invite students to begin reflecting on their own sense of place and position in the world. Reviewing the syllabus allowed students to identify how sustainability would be situated within the course.

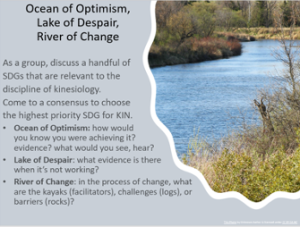

The second class accomplished many objectives. I began changing mind, heart, and skill sets by asking students to envision a world they wanted to live in. Using an adaptation of what the Sustainability Faculty Fellows have coined the “Ocean of Optimism” activity (see Figure 1), each student was able to create a personal connection with sustainability. This was a terrific way for students to envision sustainability from a broad perspective and a great segue into the SDGs. I also used this lecture to begin the reflect and share portions of “reflect, share, act” and, concurrently, to begin to practise meaningful communication with discursive teaching strategies (Van Hesteren, 2018).

In subsequent lectures, I delivered the course curriculum as I typically would; however, I invited students to draw connections to the SDGs where appropriate. At the end of select lectures, I provided students with guiding questions to facilitate reflection; throughout the course, they were encouraged to use sustainability journals to reflect on content they felt resonated with the SDGs.

I used laddering to build on concepts and support assessment. For example, students were able to use theory from psychosocial health lectures to ensure support of self-esteem in communicating with their peers and, later, with community members. We used other discursive strategies (Van Hesteren, 2018) as well as a group charter activity (Weimer, 2015) to further work on meaningful communication and nurturing relationships.

To support interdisciplinary perspectives, I brought in guest lecturers from other departments. Sharing knowledge or varying perspectives from relevant disciplines gives students a broader view of an area of study.

When we reached the final class, I provided space for students to tie everything together through summarizing, reflecting, and sharing thoughts on the interconnections between sustainability, the course content, and the discipline of kinesiology.

Assessment Strategies

Formative assessment: Throughout the course I included opportunities for students to reflect and practise through low-stakes formative assessment with feedback, including multiple opportunities to practise communication skills and relationship-building, as well as a variety of polling questions and case studies. These case studies allowed students to practise applying theory that would later be assessed in a summative manner.

Summative assessment: In addition to more traditional midterm and final exams, I had four summative assessment opportunities (students were required to complete three of four). I tried to assess a variety of learning outcomes as well as the development of student competencies while still allowing student agency where possible.

Open Educational Practices (authentic assessment, community impact, and creation of Open Educational Resources) were evident in the final course assessment. Students collaborated with a community member and created one resource for that community member and another for broader community use. An overview of each assessment, including the purpose and alignment to both the learning outcomes and student competencies, was included in the course syllabus.

The Implications

Sustainability in teaching and learning allows students to learn more about who they are and what they can do, and to develop competencies that extend beyond the classroom. This includes creating an impact in the community and, ultimately, acting toward sustainability.

The sustainability competencies they develop are skills that future employers expect from higher-education graduates. Students who can demonstrate these skills will have a marked advantage. Students have opportunities to learn, practise, and develop these skills through sustainability in teaching and learning.

In my course, using authentic assessment, students applied theoretical knowledge and collaborated with community members to develop a physical activity resource. This provided a real-world example of skills transferable to the workplace while also positively contributing to the older adult community in Saskatoon. These skills will benefit students in their professional careers and contribute to their awareness as global citizens. Students gained an understanding of their personal and professional role in creating a more sustainable future, which is a foundation for making meaningful change.

My Reflections

Throughout my journey in the SFF program, I conscientiously reflected on the experience. Sometimes reflecting more, sometimes less; most times positively, but sometimes less so.

The fellowship began at a particularly interesting and apt time. In the spring of 2022, the war in Ukraine was well underway and the world was starting to emerge from the lingering restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic, which was unduly harsh on certain demographics, escalated an existing mental health crisis, and was particularly divisive. Amid all of this, the fellowship was a beacon of hope. The SDGs outlined what I wanted my world to look like and spoke to my professional pursuits from pedagogical and disciplinary perspectives.

Personally and professionally, I strongly identified with good health and well-being (SDG 3), but I felt tension as I tried to reconcile my own health and wellness. I was feeling fatigued (perhaps the aftermath of COVID-19 or other events happening in my life at that time), and I struggled with the decision to take on the fellowship. It was somewhat ironic—as I questioned societies’ constant drive for more (the force underpinning the need for sustainability), was I doing the same? It was a project for the better good, but was it sustainable for me?

Personal sustainability was a theme throughout my fellowship experience and created tension between feelings of “survive” and “thrive,” a concept I later learned from the book Change: How Organizations Achieve Hard-to-Imagine Results in Uncertain and Volatile Times (Kotter, Akhtar, & Gupta, 2021). The driving factor for me was “heart”: sustainability was something I believed in and an area I wanted to have influence within. I used to think there was little I could do as a single being to create significant impact, but through my platform as an educator, I felt inspired to be an advocate for change. This energy pushed me away from “survive” and toward “thrive.”

To maintain this focus, I had to learn to manage expectations—especially when I felt I was not doing enough. Tracking change—continually looking back to where I started and celebrating small wins along the way—helped to sustain confidence and momentum. Equally important was the ability to pivot: recognizing what was working, building on that, and walking away from what was not. As course development is an iterative process, the results from a pre- and post-course student survey (mentioned in Chapter 1 ) were particularly helpful for future considerations.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, I did not feel as if I were charting a solo path through this process. Early in our fellowship we read Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer (2015), and the themes of reciprocity and culture of community really spoke to me. I saw these concepts in action in the fellowship as we shared thoughts and ideas, embraced different perspectives, discussed challenges, and celebrated each other’s success. I look forward to embedding sustainability in teaching and learning into more of my courses and to supporting colleagues to do the same.

Lessons Learned

Sustainability is about more than the environment. Although the environment is an imperative component, so are the social and economic pillars. Without all three, we cannot attain sustainability.

It became evident to me, working first with students and more recently with colleagues, that education on the breadth of sustainability is needed. Lack of knowledge presented the biggest barrier. If you do not understand sustainability in its entirety, it can be difficult to recognize the role you can play. Using the SDGs provided an incredible framework within which everyone could be a part of the conversation and, hopefully, the solution. There is an SDG that speaks to everyone and that works for every course. To realize global sustainability, it will take people from diverse backgrounds and areas of expertise.

Becoming comfortable with all aspects of sustainability takes time and practice. Throughout the course I questioned how much guidance I should provide in the classroom; I was unsure whether I should draw more connections between course content and the SDGs or leave it up to the students. I am still unsure and, for now, will continue to do both. Moving forward, I intend to embed sustainability in teaching and learning within required courses earlier in the program.

Working in the community takes more time and practice, for me and for the students. Shifting from a final assignment framed around a series of case studies to a collaborative project with a community member increased administrative stressors (scheduling, communication, liability). As well, it took more time and effort to move the redevelopment and assessment of student competencies from theory into practice for the first time. However, the increased effort was not undue, and it will diminish with experience.

I had always discussed with students the importance of nurturing relationships, navigating different perspectives, and communicating meaningfully, but having them work with a real, live person made that paramount. Even though we addressed effective communication practices from day one, students needed more time and support than I had anticipated. I had to adjust the lecture schedule to give students time for the practice and feedback required to succeed. Although working in the community was more stressful, the result had a positive impact on me, the students, and the community.

The biggest takeaway has been the power of heart set. As I continued to promote and raise awareness of sustainable teaching, I saw this positive heart set spread from me to my students and, ultimately, to my colleagues. A shift from “having to” toward “wanting to,” which stems from gaining a personal connection, provides a motivational boost for change (Kotter et al., 2021).

Even if the right heart set is there and change is something you have chosen, it can still feel overwhelming at first. Start with your strengths (personal, professional, course-related) and build from there, thereby mitigating stress and increasing authenticity. If you take on too much, take a step back, adjust your expectations, and remember that everything you do (no matter how small) is still one more step toward sustainability.

References

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347–364. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3448076

College of Kinesiology. (2018). Strategic plan 2025. University of Saskatchewan. https://kinesiology.usask.ca/research/welcome.php

Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of Open Educational Practices in higher education. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096

Kotter, J. P., Akhtar, V, & Gupta, G. (2021). Change: How organizations achieve hard-to-imagine results in uncertain and volatile times. Wiley.

Van Hesteren, S. (2018). Discursive strategies and thinking routines to support citizenship education inquiries. Saskatoon Public Schools. https://www.concentus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Citizenship-Education-Instructional-Strategies-Resource.pdf

Wall Kimmerer, R. (2015). Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge, and the teachings of plants. Milkweed Editions.

Weimer, M. (2015, February 26). Use team charters to improve group assignments. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/course-design-ideas/use-team-charters-improve-group-assignments/

Zawacki-Richter, O., Conrad, D., Bozkurt, A., Aydin, C. H., Bedenlier, S., Jung, I., Stöter, J., Veletsianos, G., Blaschke, L. M., Bond, M., Broens, A., Bruhn, E., Dolch, C., Kalz, M., Kerres, M., Kondakci, Y., Marin, V., Mayrberger, K., Müskens, W., … Xiao, J. (2020). Elements of open education: An invitation to future research. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 21(3), 319–334. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v21i3.4659

- This course was revamped and not designed from a blank slate, so I want to acknowledge efforts and contributions from previous instructors: D. Drinkwater, W. Duff, H. Foulds, and J. Gordan. ↵