8 Module 8: Social Identities: Sex, Gender and Sexuality

Learning Objectives

- Define and differentiate between sex, gender, and sexuality.

- Describe the relationship between society and biology in formations of gender identity.

- Discuss the role of homophobia and heterosexism in society.

- Distinguish between transgendered, transsexual, intersexual, and homosexual identities.

- Describe the dominant gender schema and how it influences social perceptions of sex and gender.

- Explain the influence of socialization on gender roles in Canada.

- Discuss the effect of gender inequality in major North American institutions.

- Describe different attitudes associated with sex and sexuality.

- Define sexual inequality in various societies.

8.0 Introduction to Gender, Sex, and Sexuality

In 2009, the 18-year old South African athlete, Caster Semenya, won the women’s 800-meter world championship in Track and Field. Her time of 1:55:45, a surprising improvement from her 2008 time of 2:08:00, caused officials from the International Association of Athletics Foundation (IAAF) to question whether her win was legitimate. If this questioning were based on suspicion of steroid use, the case would be no different from that of Roger Clemens or Mark McGuire, or even Track and Field Olympic gold medal winner Marion Jones. But the questioning and eventual testing were based on

allegations that Caster Semenya, no matter what gender identity she possessed, was biologically a male.

You may be thinking that distinguishing biological maleness from biological femaleness is surely a simple matter — just conduct some DNA or hormonal testing, throw in a physical examination, and you’ll have the answer. But it is not that simple. Both biologically male and biologically female people produce a certain amount of testosterone, and different laboratories have different testing methods, which makes it difficult to set a specific threshold for the amount of male hormones produced by a female that renders her sex male. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) criteria for determining

eligibility for sex-specific events are not intended to determine biological sex. “Instead these regulations are designed to identify circumstances in which a particular athlete will not be eligible (by reason of hormonal characteristics) to participate in the 2012 Olympic Games” in the female category (International Olympic Committee, 2012).

To provide further context, during the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, eight female athletes with XY chromosomes underwent testing and were ultimately confirmed as eligible to compete as women (Maugh, 2009). To date, no males have undergone this sort of testing. Does this not imply that when women perform better than expected, they are “too masculine,” but when men perform well they are simply superior athletes? Can you imagine Usain Bolt, the world’s fastest man, being examined by doctors to prove he was biologically male based solely on his appearance and athletic ability? Can you explain how sex, sexuality, and gender are different from each other?

In this Module, we will discuss the differences between sex and gender, along with issues like gender identity and sexuality. What does it mean to “have” a sex in our society? What does it mean to “have” a sexuality? We will also explore various theoretical perspectives on the subjects of gender and sexuality.

Feminist sociology is particularly attuned to the way that most cultures present a male-dominated view of the world as if it were simply the view of the world. Androcentricism is a perspective in which male concerns, male attitudes, and male practices are presented as “normal” or define what is significant and valued in a culture. Women’s experiences, activities, and contributions to society and history are ignored, devalued, or marginalized.

As a result the perspectives, concerns, and interests of only one sex and class are represented as general. Only one sex and class are directly and actively involved in producing, debating, and developing its ideas, in creating its art, in forming its medical and psychological conceptions, in framing its laws, its political principles, its educational values and objectives. Thus a one-sided standpoint comes to be seen as natural, obvious, and general, and a one-sided set of interests preoccupy intellectual and creative work. (Smith, 1987)

In part this is simply a question of the bias of those who have the power to define cultural values, and in part it is the result of a process in which women have been actively excluded from the culture-creating process. It is still common, for example, to read writing that uses the personal pronoun “he” or the word “man” to represent people in general or humanity. The overall effect is to establish masculine values and imagery as normal. A “policeman” brings to mind a man who is doing a “man’s job”, when in fact women have been involved in policing for several decades now.

8.1. The Difference between Sex, Gender, and Sexuality

When filling out a document such as a job application or school registration form you are often asked to provide your name, address, phone number, birth date, and sex or gender. But have you ever been asked to provide your sex and your gender? As with most people, it may not have occurred to you that sex and gender are not the same. However, sociologists and most other social scientists view sex and gender as conceptually distinct. Sex refers to physical or physiological differences between males and females, including both primary sex characteristics (the reproductive system) and secondary characteristics such as height and muscularity. Gender is a term that refers to social or cultural distinctions and roles associated with being male or female. Gender identity is the extent to which one identifies as being either masculine or feminine (Diamond, 2002). As gender is such a primary dimension of identity, socialization, institutional participation, and life chances, sociologists refer to it as a core status.

The distinction between sex and gender is key to being able to examine gender and sexuality as social variables rather than biological variables. Contrary to the common way of thinking about it, gender is not determined by biology in any simple way. For example, the anthropologist Margaret Mead‛s cross cultural research in New Guinea, in the 1930s, was groundbreaking in its demonstration that cultures differ markedly in the ways that they perceive the gender “temperments” of men and women; i.e., their masculinity and femininity (Mead, 1963). Unlike the qualities that defined masculinity and femininity in North America at the time, she saw both genders among the Arapesh as sensitive, gentle, cooperative, and passive, whereas among the Mundugumor both genders were assertive, violent, jealous, and aggressive. Among the Tchambuli, she described male and female temperaments as the opposite of those observed in North America. The women appeared assertive, domineering, emotionally inexpressive, and managerial, while the men appeared emotionally dependent, fragile, and less responsible.

The experience of transgendered people also demonstrates that a person’s sex, as determined by his or her biology, does not always correspond with his or her gender. Therefore, the terms sex and gender are not interchangeable. A baby boy who is born with male genitalia will be identified as male. As he grows, however, he may identify with the feminine aspects of his culture. Since the term sex refers to biological or physical distinctions, characteristics of sex will not vary significantly between different human societies. For example, it is physiologically normal for persons of the female sex, regardless of culture, to eventually menstruate and develop breasts that can lactate. The signs and characteristics of gender, on the other hand, may vary greatly between different societies as Margaret Mead’s research noted. For example, in American culture, it is considered feminine (or a trait of the female gender) to wear a dress or skirt. However, in many Middle Eastern, Asian, and African cultures, dresses or skirts (often referred to as sarongs, robes, or gowns) can be considered masculine. The kilt worn by a Scottish male does not make him appear feminine in his culture.

The dichotomous view of gender (the notion that one is either male or female) is specific to certain cultures and is not universal. In some cultures, gender is viewed as fluid. In the past, some anthropologists used the term berdache or two spirit person to refer to individuals who occasionally or permanently dressed and lived as the opposite gender. The practice has been noted among certain Aboriginal groups (Jacobs, Thomas, and Lang, 1997). Samoan culture accepts what they refer to as a “third gender.” Fa’afafine, which translates as “the way of the woman,” is a term used to describe individuals who are born biologically male but embody both masculine and feminine traits. Fa’afafines are considered an important part of Samoan culture. Individuals from other cultures may mislabel them as homosexuals because fa’afafines have a varied sexual life that may include men or women (Poasa, 1992).

8.1.1 Sexuality

Sexuality refers to a person’s capacity for sexual feelings and their emotional and sexual attraction to a particular sex (male or female). Sexuality or sexual orientation is typically divided into four categories: heterosexuality, the attraction to individuals of the opposite sex; homosexuality, the attraction to individuals of one’s own sex; bisexuality, the attraction to individuals of either sex; and asexuality, no attraction to either sex. Heterosexuals and homosexuals may also be referred to informally as “straight” and “gay,” respectively. North America is a heteronormative society, meaning it supports heterosexuality as the norm, (referred to as heteronormativity). Consider that homosexuals are often asked, “When did you know you were gay?” but heterosexuals are rarely asked, “When did you know that you were straight?” (Ryle, 2011).

According to current scientific understanding, individuals are usually aware of their sexual orientation between middle childhood and early adolescence (American Psychological Association, 2008). They do not have to participate in sexual activity to be aware of these emotional, romantic, and physical attractions; people can be celibate and still recognize their sexual orientation. Homosexual women (also referred to as lesbians), homosexual men (also referred to as gays), and bisexuals of both genders may have very different experiences of discovering and accepting their sexual orientation. At the point of puberty, some may be able to claim their sexual orientations while others may be unready or unwilling to make their homosexuality or bisexuality known since it goes against North American society’s historical norms (APA, 2008).

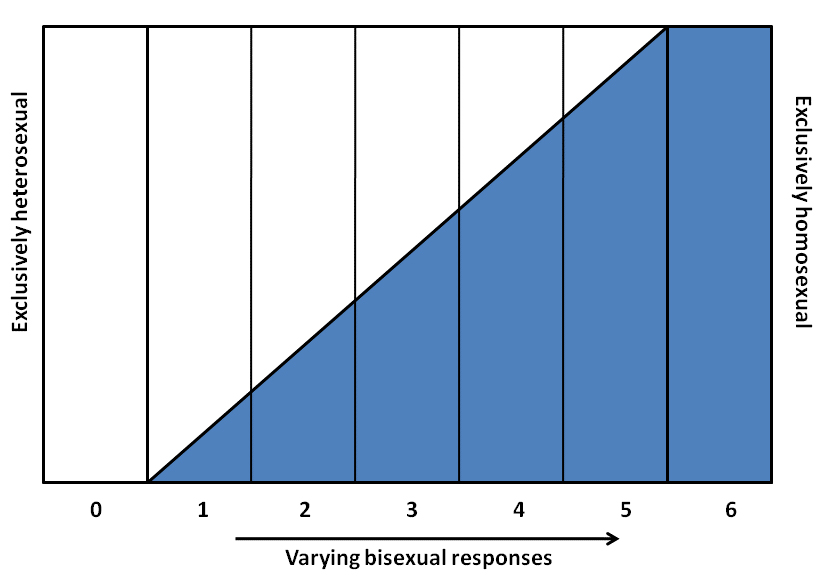

Alfred Kinsey was among the first to conceptualize sexuality as a continuum rather than a strict dichotomy of gay or straight. To classify this continuum of heterosexuality and homosexuality, Kinsey created a six-point rating scale that ranges from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual (see Figure 12.4). In his 1948 work Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Kinsey writes, “Males do not represent two discrete populations, heterosexual and homosexual. The world is not to be divided into sheep and goats … The living world is a continuum in each and every one of its aspects” (Kinsey et al, 1948).

Later scholarship by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick expanded on Kinsey’s notions. She coined the term “homosocial” to oppose “homosexual,” describing nonsexual same-sex relations. Sedgwick recognized that in North American culture, males are subject to a clear divide between the two sides of this continuum, whereas females enjoy more fluidity. This can be illustrated by the way women in Canada can express homosocial feelings (nonsexual regard for people of the same sex) through hugging, hand-holding, and physical closeness. In contrast, Canadian males refrain from these expressions since they violate the heteronormative expectation. While women experience a flexible norming of variations of behaviour that spans the heterosocial-homosocial spectrum, male behaviour is subject to strong social sanction if it veers into homosocial territory because of societal homophobia (Sedgwick, 1985).

There is no scientific consensus regarding the exact reasons why an individual holds a heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual orientation. There has been research conducted to study the possible genetic, hormonal, developmental, social, and cultural influences on sexual orientation, but there has been no evidence that links sexual orientation to one factor (APA, 2008). Research, however, does present evidence showing that homosexuals and bisexuals are treated differently than heterosexuals in schools, the workplace, and the military. The 2009 Canadian Climate Survey reported that 59% of LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgendered) high school students had been subject to verbal harassment at school compared to 7% of non-LGBT students; 25% had been subject to physical harassment compared to 8% of non-LGBT students; 31% had been subject to cyber-bullying (via internet or text messaging) compared to 8% of non-LGBT students; 73% felt unsafe at school compared to 20% of non-LGBT students; and 51% felt unaccepted at school compared to 19% of non-LGBT students (Taylor and Peter, 2011).

Much of this discrimination is based on stereotypes, misinformation, and homophobia — an extreme or irrational aversion to homosexuals. Major policies to prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation have not come into effect until the last few years. In 2005, the federal government legalized same-sex marriage. The Civil Marriage Act now describes marriage in Canada in gender neutral terms: “Marriage, for civil purposes, is the lawful union of two persons to the exclusion of all others” (Civil Marriage Act, S.C. 2005, c. 33). The Canadian Human Rights Act was amended in 1996 to explicitly prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation, including the unequal treatment of gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals. Organizations such as Egale Canada (Equality for Gays And Lesbians Everywhere) advocate for LGBT rights, establish gay pride organizations in Canadian communities, and promote gay-straight alliance support groups in schools. Advocacy agencies frequently use the acronym LGBTQ, which stands for “lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered,” and “queer” or “questioning.”

8.1.2 Gender Roles

Moral development is an important part of the socialization process. The term refers to the way people learn what society considers to be “good” and “bad,” which is important for a smoothly functioning society. Moral development prevents people from acting on unchecked urges, instead considering what is right for society and good for others. Lawrence Kohlberg (1927–1987) was interested in how people learn to decide what is right and what is wrong. To understand this topic, he developed a theory of moral development that includes three levels: preconventional, conventional, and postconventional.

In the preconventional stage, young children, who lack a higher level of cognitive ability, experience the world around them only through their senses. It is not until the teen years that the conventional theory develops, when youngsters become increasingly aware of others’ feelings and take those into consideration when determining what’s good and bad. The final stage, called postconventional, is when people begin to think of morality in abstract terms, such as North Americans believing that everyone has equal rights and freedoms. At this stage, people also recognize that legality and morality do not always match up evenly (Kohlberg, 1981). When hundreds of thousands of Egyptians turned out in 2011 to protest government autocracy, they were using postconventional morality. They understood that although their government was legal, it was not morally correct.

Carol Gilligan (b. 1936), recognized that Kohlberg’s theory might show gender bias since his research was conducted only on male subjects. Would female study subjects have responded differently? Would a female social scientist notice different patterns when analyzing the research? To answer the first question, she set out to study differences between how boys and girls developed morality. Gilligan’s research demonstrated that boys and girls do, in fact, have different understandings of morality. Boys tend to have a justice perspective, placing emphasis on rules, laws, and individual rights. They learn to morally view the world in terms of categorization and separation. Girls, on the other hand, have a care and responsibility perspective; they are concerned with responsibilities to others and consider people’s reasons behind behaviour that seems morally wrong. They learn to morally view the world in terms of connectedness.

Gilligan also recognized that Kohlberg’s theory rested on the assumption that the justice perspective was the right, or better, perspective. Gilligan, in contrast, theorized that neither perspective was “better”: The two norms of justice served different purposes. Ultimately, she explained that boys are socialized for a work environment where rules make operations run smoothly, while girls are socialized for a home environment where flexibility allows for harmony in caretaking and nurturing (Gilligan, 1982, 1990).

As we grow, we learn how to behave from those around us. In this socialization process, children are introduced to certain roles that are typically linked to their biological sex. The term gender role refers to society’s concept of how men and women are expected to act and how they should behave. These roles are based on norms, or standards, created by society. In Canadian culture, masculine roles are usually associated with strength, aggression, and dominance, while feminine roles are usually associated with passivity, nurturing, and subordination. Role learning starts with socialization at birth. Even today, our society is quick to outfit male infants in blue and girls in pink, even applying these colour-coded gender labels while a baby is in the womb.

How do girls and boys learn different gender roles? Gender differences in the ways boys and girls play and interact develop from a very early age, sometimes despite the efforts of parents to raise them in a gender neutral way. Little boys seem inevitably to enjoy running around playing with guns and projectiles, while little girls like to study the effects of different costumes on toy dolls. Peggy Orenstein (2012) describes how her two-year-old daughter happily wore her engineer outfit and took her Thomas the Tank Engine lunchbox to the first day of preschool. It only took one little boy to say to her that “girls don’t like trains!” for her to ditch Thomas and move on to more gender “appropriate” concerns like princesses. If gender preferences are not inborn or biologically hard-wired, how do sociologists explain them?

As the Thomas the Tank Engine example suggests, doing gender — performing tasks based upon the gender assigned by society — is learned through interaction with others in much the same way that Mead and Cooley described for socialization in general. Children learn gender through direct feedback from others, particularly when they are censured for violating gender norms. Gender is in this sense an accomplishment rather than an innate trait. It takes place through the child’s developing awareness of self. Whereas in the Freudian model of gender development children become aware of their own genitals and spontaneously generate erotic fantasies and speculations whose resolution lead them to identify with their mother or father, in the sociological model, it is adults’ awareness of a child’s genitals that leads to gender labelling, differential reinforcement and the assumption of gender roles.

From a very early age children develop a gender schema, a rudimentary image of gender differences, that enables them to make decisions about appropriate styles of play and behaviour (Fagot & Leinbach, 1989). As they integrate their sense of self into this developing schema, they gradually adopt consistent and stable gender roles. Consistency and stability do not mean that the gender roles that are learned are permanent, however, as would be suggested by a biological or hard-wired model of gender. Physical expressions of gender such as “throwing like a girl” can be transformed into a new stable gender schema when the little girl joins a softball league.

Fagot and Leinbach’s (1986, 1989) research into the development of gender schemas showed that very young children, averaging about two years old, could not correctly classify photographs of adults and children by their gender; whereas, slightly older children, averaging 2.5 years old, could. They concluded that the younger children had not yet developed a gender schema. They also observed that the older children who could correctly classify the photos by gender demonstrated gender specific play; they tended to choose same-gender play groups and girls were less aggressive in their play. The older children were integrating their sense of self into their gender schemas and behaving accordingly.

Similarly, when they studied children at home, they found that children at age 1.5 could not assign gender to photographs correctly and did not engage in gender-typed play. However, by age 2.25 years about half of the children could classify the photos and were engaging in gender specific play. These “early labellers” were distinguished from those who could not classify photos by the way their parents interacted with them. Parents of early adopters were more likely to use differential reinforcement in the form of positive and negative responses to gender-typed toy play.

It is interesting, with respect to the difference between the Freudian and sociological models of gender socialization, that the gender schemas of young children develop with respect to external cultural signs of gender rather than biological markers of genital differences. Sandra Bem (1989) showed young children photos of either a naked child or a child dressed in boys or girls clothing. The younger children had difficulty classifying the naked photos but could classify the clothed photos. They did not have an understanding of biological sex constancy — i.e. the ability to determine sex based on anatomy regardless of gender signs — but used cultural signs of gender like clothing or hair style to determine gender. Moreover, it was the gender schema and not the recognition of anatomical differences that first determined their choice of gender-typed toys and gender-typed play groups. Bem suggested that “children who can label the sexes but do not understand anatomical stability are not yet confident that they will always remain in one gender group” (1989).

One way children learn gender roles is through play. Parents typically supply boys with trucks, toy guns, and superhero paraphernalia, which are active toys that promote motor skills, aggression, and solitary play. Girls are often given dolls and dress-up apparel that foster nurturing, social proximity, and role play. Studies have shown that children will most likely choose to play with “gender appropriate” toys (or same-gender toys) even when cross-gender toys are available because parents give children positive feedback (in the form of praise, involvement, and physical closeness) for gender-normative behaviour (Caldera, Huston, and O’Brien, 1998).

8.1.3 Gender Identity

Canadian society allows for some level of flexibility when it comes to acting out gender roles. To a certain extent, men can assume some feminine roles and characteristics and women can assume some masculine roles and characteristics without interfering with their gender identity. Gender identity is an individual’s self-conception of being male or female based on his or her association with masculine or feminine gender roles.

As opposed to cisgendered individuals, who identify their gender with the gender and sex they were assigned at birth, individuals who identify with the gender that is the opposite of their biological sex are transgendered. Transgendered males, for example, although assigned the sex ‘female’ at birth, have such a strong emotional and psychological connection to the forms of masculinity in society that they identify their gender as male. The parallel connection to femininity exists for transgendered females. It is difficult to determine the prevalence of transgenderism in society. Statistics Canada states that they have neither the definitive number of people whose sexual orientation is lesbian, gay, or bisexual, nor the number of people who are transgendered (Statistics Canada, 2011). However, it is estimated that 2 to 5% of the U.S. population is transgendered (Transgender Law and Policy Institute, 2007).

Transgendered individuals who wish to alter their bodies through medical interventions such as surgery and hormonal therapy — so that their physical being is better aligned with their gender identity — are called transsexuals. They may also be known as male-to-female (MTF) or female-to-male (FTM) transsexuals. Not all transgendered individuals choose to alter their bodies: many will maintain their original anatomy but may present themselves to society as the opposite gender. This is typically done by adopting the dress, hairstyle, mannerisms, or other characteristic typically assigned to the opposite gender. It is important to note that people who cross-dress, or wear clothing that is traditionally assigned to the opposite gender, are not necessarily transgendered. Cross-dressing is typically a form of self-expression, entertainment, or personal style, not necessarily an expression of gender identity (APA, 2008).

There is no single, conclusive explanation for why people are transgendered. Transgendered expressions and experiences are so diverse that it is difficult to identify their origin. Some hypotheses suggest biological factors such as genetics, or prenatal hormone levels, as well as social and cultural factors, such as childhood and adulthood experiences. Most experts believe that all of these factors contribute to a person’s gender identity (APA, 2008).

It is known that transgendered and transsexual individuals experience discrimination based on their gender identity. People who identify as transgendered are twice as likely to experience assault or discrimination as non-transgendered individuals; they are also one and a half times more likely to experience intimidation (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, 2010). Organizations such as the Canadian Professional Association for Transgender Health (CPATH), Trans Pulse, and the National Center for Trans Equality work to support and prevent, respond to, and end all types of violence against transgendered, transsexual, and homosexual individuals. These organizations hope that by educating the public about gender identity and empowering transgendered and transsexual individuals, this violence will end.

8.1.4 The Dominant Gender Schema

As sociological research points out, the naturalness with which one assumes a gender identity of being either masculine or feminine, or a sexual identity of being sexually attracted to either men or women, has a significant social component. Gender and sexual identities are deep identities in the sense that one does not seem to choose them. They seem to “come over” one, sometimes at a very early age, and thereafter appear for most people to be fixed. Nevertheless they are sustained by social norms and conventions. This social aspect of gender or sexual identity is revealed especially through the research tradition in sociology that focuses on those who break the rules of society. By studying those who break the rules, the rules themselves and what they entail become visible. In the study of gender and sexuality, the experience of intersexuals, transgendered individuals, transsexuals, gays, lesbians, bisexuals, fetishists, and sexual “perverts,” etc. are invaluable for understanding what it means to have a gender or a sexuality. These individuals make up a minority of the population (maybe?), but their lives and struggles reveal the existence of the social norms and processes of which others are often unaware.

Part of having a sexuality or a gender has to do with the “naturalness” with which an individual assumes one of the most fundamental identities that define their place in the world. However, having a gender or sexual identity only appears natural to the degree that one fits within the dominant gender schema (Devor, 2000). The dominant gender schema is an ideology that, like all ideologies, serves to perpetuate inequalities in power and status. This schema states that: a) sex is a biological characteristic that produces only two options, male or female, and b) gender is a social or psychological characteristic that manifests or expresses biological sex. Again, only two options exist, masculine or feminine: “All persons are either one gender or the other. No person can be neither. No person can be both. No person can change gender without major medical intervention” (Devor, 2000).

For many people this is natural. It goes without saying. However, if one does not fit within the dominant gender schema, then the naturalness of one’s gender identity is thrown into question. This occurs, first of all, by the actions of external authorities and experts who define those who do not fit as either mistakes of nature or as products of failed socialization and individual psychopathology. Gender identity is also thrown into question by the actions of peers and family who respond with concern or censure when a girl is not feminine enough or a boy is not masculine enough. Moreover, the ones who do not fit also have questions. They may begin to wonder why the norms of society do not reflect their sense of self, and thus begin to feel at odds with the world.

As the capacity to differentiate between the genders is the basis of patriarchal relations of power that have existed for 6,000 years, the dominant gender schema is one of the fundamental organizing principles that maintains the dominant societal order. Nevertheless, it is only a schema: a cultural distinction that is imposed upon the diversity of world. With respect to the biology of gender and sexuality, Anne Fausto-Sterling (2000) argues that a body’s sex is too complex to fit within the obligatory dual sex system, and ultimately, the decision to label someone male or female is a social decision.

Fausto-Sterling’s research on hermaphrodite or intersex children — the 1.7% of children who are born with a mixture of male and female sexual organs — indicates that there are at least five different sexes:

- male;

- female;

- herms: true hermaphrodites with both male and female gonads (i.e., testes and ovaries);

- merms: male pseudo-hermaphrodites with testes and a mixture of sexual organs; and

- ferms: female pseudo-hermaphrodites with ovaries and a mixture of sexual organs.

Nevertheless, because assigning a sex identity is a fundamental cultural priority, doctors will typically decide “nature’s intention” with respect to intersex babies within 24 hours of an intersex child being born. Sometimes this decision involves surgery, which has scarred individuals for life (Fausto-Sterling, 2000).

Similarly, with respect to the variability of gender and sexuality, the experiences of gender and sexual outsiders — homosexuals, bisexuals, transsexuals, women who do not look or act “feminine” and men who do not look or act “masculine,” etc. — reveal the subtle dramaturgical order of social processes and negotiations through which all gender identity is sustained and recognized by others (Goffman’s dramaturgical analysis was discussed in Module 6). Because we do not usually have the capacity to “look under the hood” to clinically determine the sex of someone we encounter, we read their gender from their “gender display”– their “conventionalized portrayals” of the “culturally established correlates of sex” (Goffman, 1977). Gender is a performance which is enhanced by props like clothing and hairstyle, or mannerisms like tone of voice, physical bearing, and facial expression.

For a movie star like Marilyn Munroe, the gender display is exaggerated almost to the point of self-satire, whereas for gender blending women — women who do not dress or look stereotypically like women — the gender display can be (unintentionally) ambiguous to the point where they are often mistaken for men (Devor, 2000). The signs of gender need to be communicated in an unambiguous manner for an individual to “pass” as a member of their assigned gender. This is often a problem for transgendered and transsexual individuals and the cause of considerable stress and anxiety.

Video: The Transgender Journey: Struggle for Rights and Respect. (https://www.cpac.ca/en/transgender-journey/)

“This 60-minute documentary gives voice to transgender Canadians of all ages, from children and young adults to married couples and senior citizens. They tell their personal stories about why they transitioned and the challenges they face, like bullying and violence, discrimination and barriers to health care. As the trans community becomes more visible and more vocal, the documentary also looks at the continuing struggle for equal rights, recognition and respect.”

8.2. Gender and Society

8.2.1 Gender and Socialization

The organization of society is profoundly gendered, meaning that the “natural” distinction between male and female, and the attribution of different qualities to each, underlies institutional structures from the family, to the occupational structure, to the division between public and private, to access to power and beyond. Patriarchy is the set of institutional structures (like property rights, access to positions of power, and relationship to sources of income) which are based on the belief that men and women are dichotomous and unequal categories. How does the “naturalness” of the distinction between male and female get established? How does it serve to organize everyday life?

The phrase “boys will be boys” is often used to justify behaviour such as pushing, shoving, or other forms of aggression from young boys. The phrase implies that such behaviour is unchangeable and something that is part of a boy’s nature. Aggressive behaviour, when it does not inflict significant harm, is often accepted from boys and men because it is congruent with the cultural script for masculinity. The “script” written by society is in some ways similar to a script written by a playwright. Just as a playwright expects actors to adhere to a prescribed script, society expects women and men to behave according to the expectations of their respective gender role. Scripts are generally learned through socialization, which teaches people to behave according to social norms.

Socialization

Children learn at a young age that there are distinct expectations for boys and girls. Cross-cultural studies reveal that children are aware of gender roles by age two or three. At four or five, most children are firmly entrenched in culturally appropriate gender roles (Kane, 1996). Children acquire these roles through socialization, a process in which people learn to behave in a particular way as dictated by societal values, beliefs, and attitudes. For example, society often views riding a motorcycle as a masculine activity and, therefore, considers it to be part of the male gender role. Attitudes such as this are typically based on stereotypes — oversimplified notions about members of a group. Gender stereotyping involves overgeneralizing about the attitudes, traits, or behaviour patterns of women or men. For example, women may be thought of as too timid or weak to ride a motorcycle.

Gender stereotypes form the basis of sexism. Sexism refers to prejudiced beliefs that value one sex over another. Sexism varies in its level of severity. In parts of the world where women are strongly undervalued, young girls may not be given the same access to nutrition, health care, and education as boys. Further, they will grow up believing that they deserve to be treated differently from boys (Thorne, 1993; UNICEF, 2007). While illegal in Canada when practised as discrimination, unequal treatment of women continues to pervade social life. It should be noted that discrimination based on sex occurs at both the micro- and macro-levels. Many sociologists focus on discrimination that is built into the social structure; this type of discrimination is known as institutional discrimination (Pincus, 2008).

Gender socialization occurs through four major agents of socialization: family, education, peer groups, and mass media. Each agent reinforces gender roles by creating and maintaining normative expectations for gender-specific behaviour. Exposure also occurs through secondary agents such as religion and the workplace. Repeated exposure to these agents over time leads men and women into a false sense that they are acting naturally rather than following a socially constructed role.

Family is the first agent of socialization. There is considerable evidence that parents socialize sons and daughters differently. Generally speaking, girls are given more latitude to step outside of their prescribed gender role (Coltrane and Adams, 2004; Kimmel, 2000; Raffaelli and Ontai, 2004). However, differential socialization typically results in greater privileges afforded to boys. For instance, sons are allowed more autonomy and independence at an earlier age than daughters. They may be given fewer restrictions on appropriate clothing, dating habits, or curfew. Sons are also often free from performing domestic duties such as cleaning or cooking, and other household tasks that are considered feminine. Daughters are limited by their expectation to be passive, nurturing, and generally obedient, and to assume many of the domestic responsibilities.

Even when parents set gender equality as a goal, there may be underlying indications of inequality. For example, when dividing up household chores, boys may be asked to take out the garbage or perform other tasks that require strength or toughness, while girls may be asked to fold laundry or perform duties that require neatness and care. It has been found that fathers are firmer in their expectations for gender conformity than are mothers, and their expectations are stronger for sons than they are for daughters (Kimmel, 2000). This is true in many types of activities, including preference of toys, play styles, discipline, chores, and personal achievements. As a result, boys tend to be particularly attuned to their father’s disapproval when engaging in an activity that might be considered feminine, like dancing or singing (Coltrane and Adams, 2008). It should be noted that parental socialization and normative expectations vary along lines of social class, race, and ethnicity. Research in the United States has shown that African American families, for instance, are more likely than Caucasians to model an egalitarian role structure for their children (Staples and Boulin Johnson, 2004).

The reinforcement of gender roles and stereotypes continues once a child reaches school age. Until very recently, schools were rather explicit in their efforts to stratify boys and girls. The first step toward stratification was segregation. Girls were encouraged to take home economics or humanities courses and boys to take shop, math, and science courses.

Studies suggest that gender socialization still occurs in schools today, perhaps in less obvious forms (Lips, 2004). Teachers may not even realize that they are acting in ways that reproduce gender-differentiated behaviour patterns. Yet, any time they ask students to arrange their seats or line up according to gender, teachers are asserting that boys and girls should be treated differently (Thorne, 1993).

Even in levels as low as kindergarten, schools subtly convey messages to girls indicating that they are less intelligent or less important than boys. For example, in a study involving teacher responses to male and female students, data indicated that teachers praised male students far more than their female counterparts. Additionally, teachers interrupted girls more and gave boys more opportunities to expand on their ideas (Sadker and Sadker, 1994). Further, in social as well as academic situations, teachers have traditionally positioned boys and girls oppositionally — reinforcing a sense of competition rather than collaboration (Thorne, 1993). Boys are also permitted a greater degree of freedom regarding rule-breaking or minor acts of deviance, whereas girls are expected to follow rules carefully and to adopt an obedient posture (Ready, 2001). Schools reinforce the polarization of gender roles and the age-old “battle of the sexes” by positioning girls and boys in competitive arrangements.

Mimicking the actions of significant others is the first step in the development of a separate sense of self (Mead, 1934). Like adults, children become agents who actively facilitate and apply normative gender expectations to those around them. When children do not conform to the appropriate gender role, they may face negative sanctions such as being criticized or marginalized by their peers. Though many of these sanctions are informal, they can be quite severe. For example, a girl who wishes to take karate class instead of dance lessons may be called a “tomboy” and face difficulty gaining acceptance from both male and female peer groups (Ready, 2001). Boys, especially, are subject to intense ridicule for gender nonconformity (Coltrane and Adams, 2008; Kimmel, 2000).

Mass media serves as another significant agent of gender socialization. In television and movies, women tend to have less significant roles and are often portrayed as wives or mothers. When women are given a lead role, they are often one of two extremes: a wholesome, saint-like figure or a malevolent, hypersexual figure (Etaugh and Bridges, 2003). This same inequality is pervasive in children’s movies (Smith, 2008). Research indicates that of the 101 top-grossing G-rated movies released between 1990 and 2005, three out of four characters were male. Out of those 101 movies, only seven were near being gender balanced, with a character ratio of less than 1.5 males per 1 female (Smith, 2008).

Television commercials and other forms of advertising also reinforce inequality and gender-based stereotypes. Women are almost exclusively present in ads promoting cooking, cleaning, or child care-related products (Davis, 1993). Think about the last time you saw a man star in a dishwasher or laundry detergent commercial. In general, women are underrepresented in roles that involve leadership, intelligence, or a balanced psyche. Of particular concern is the depiction of women in ways that are dehumanizing, especially in music videos. Even in mainstream advertising, however, themes intermingling violence and sexuality are quite common (Kilbourne, 2000).

Social Stratification and Inequality

How do the distinctions between male and female, and the social attribution of different qualities to each, serve to organize our institutions (the family, occupational structure, and the public/private divide, etc.)? How do these distinctions organize differential access to rewards, privileges, and power? In society, how and why are women not treated as the equals of men?

8.2.2 Her-story: The History of Gender Inequality

Missing in the classical theoretical accounts of modernity is an explanation of how the developments of modern society, industrialization, and capitalism have affected women differently from men. Despite the differences in Durkheim’s, Marx’s, and Weber’s main themes of analysis, they are equally androcentric to the degree that they cannot account for why women’s experience of modern society is structured differently from men’s, or why the implications of modernity are different for women than they are for men. They tell his-story but neglect her-story.

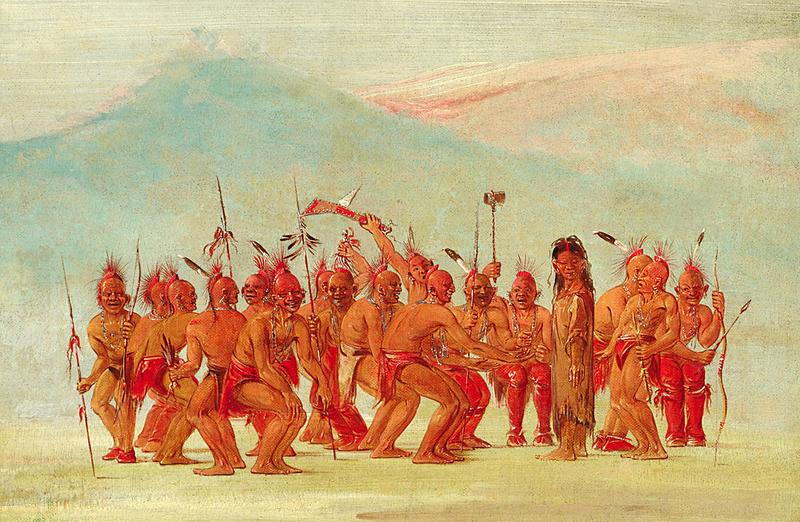

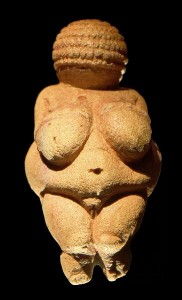

For most of human history, men and women held more or less equal status in society. In hunter-gatherer societies gender inequality was minimal as these societies did not sustain institutionalized power differences. They were based on cooperation, sharing, and mutual support. There was often a gendered division of labour in that men are most frequently the hunters and women the gatherers and child care providers (although this division is not necessarily strict), but as women’s gathering accounted for up to 80% of the food, their economic power in the society was assured. Where headmen lead tribal life, their leadership is informal, based on influence rather than institutional power (Endicott, 1999). In prehistoric Europe from 7000 to 3500 BCE, archaeological evidence indicates that religious life was in fact focused on female deities and fertility, while family kinship was traced through matrilineal (female) descent (Lerner, 1986).

It was not until about 6,000 years ago that gender inequality emerged. With the transition to early agrarian and pastoral types of societies, food surpluses created the conditions for class divisions and power structures to develop (as discussed in Module 7). Property and resources passed from collective ownership to family ownership with a corresponding shift in the development of the monogamous, patriarchal (rule by the father) family structure. Women and children also became the property of the patriarch of the family. The invasions of old Europe by the Semites to the south, and the Kurgans to the northeast, led to the imposition of male-dominated hierarchical social structures and the worship of male warrior gods. As agricultural societies developed, so did the practice of slavery. Lerner (1986) argues that the first slaves were women and children.

The development of modern, industrial society has been a two-edged sword in terms of the status of women in society. Marx’s collaborator Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) argued in The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884/1972) that the historical development of the male-dominated monogamous family originated with the development of private property. The family became the means through which property was inherited through the male line. This also led to the separation of a private domestic sphere and a public social sphere. “Household management lost its public character. It no longer concerned society. It became a private service; the wife became the head servant, excluded from all participation in social production” (1884/1972). Under the system of capitalist wage labour, women were doubly exploited. When they worked outside the home as wage labourers they were exploited in the workplace, often as cheaper labour than men. When they worked within the home, they were exploited as the unpaid source of labour needed to reproduce the capitalist workforce. The role of the proletarian housewife was tantamount to “open or concealed domestic slavery” as she had no independent source of income herself (Engels, 1884/1972). Early Canadian law, for example, was based on the idea that the wife’s labour belonged to the husband. This was the case even up to the famous divorce case of Irene Murdoch in 1973, who had worked the family farm in the Turner Valley, Alberta, side by side with her husband for 25 years. When she claimed 50% of the farm assets in the divorce, the judge ruled that the farm belonged to her husband, and she was awarded only $200 a month for a lifetime of work (CBC, 2001).

On the other hand, feminists note that gender inequality was more pronounced and permanent in the feudal and agrarian societies that proceeded capitalism. Women were more or less owned as property, and were kept ignorant and isolated within the domestic sphere. These conditions still exist in the world today. The World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap Report (2014) shows that in a significant number of countries women are severely restricted with respect to economic participation, educational attainment, political empowerment, and basic health outcomes. Yemen, Pakistan, Chad, Syria, and Mali were the five worst countries in the world in terms of women’s inequality.

Yemen is the world’s worst country for women in 2014, according to the WEF. In addition to being one of the worst countries in women’s economic participation and opportunity, Yemen received some of the world’s worst scores in relative educational attainment and political participation for females. Just half of women in the country could read, versus 83% of men. Further, women accounted for just 9% of ministerial positions and for none of the positions in parliament. Child marriage is a huge problem in Yemen. According to Human Rights Watch, as of 2006, 52% of Yemeni girls were married before they reached 18, and 14% were married before they reached 15 years of age (Hess, 2014).

With the rise of capitalism, Engels noted that there was also an improvement in women’s condition when they began to work outside the home. Writers like Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) in her Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792/1997) were also able to see, in the discourses of rights and freedoms of the bourgeois revolutions and the Enlightenment, a general “promise” of universal emancipation that could be extended to include the rights of women. The focus of the Vindication of the Rights of Women was on the right of women to have an education, which would put them on the same footing as men with regard to the knowledge and rationality required for “enlightened” political participation and skilled work outside the home. Whereas property rights, the role of wage labour, and the law of modern society continued to be a source for gender inequality, the principles of universal rights became a powerful resource for women to use in order to press their claims for equality.

As the World Economic Forum (2014) study reports, “good progress has been made over the last years on gender equality, and in some cases, in a relatively short time.” Between 2006 and 2014, the gender gap in the measures of economic participation, education, political power, and health narrowed for 95% of the 111 countries surveyed. In the top five countries in the world for women’s equality — Iceland, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark — the global gender gap index had closed to 80% or better. (Canada was 19th with a global gender gap index of 75%).

Stratification refers to a system in which groups of people experience unequal access to basic, yet highly valuable, social resources. According to George Murdock’s classic work, Outline of World Cultures (1954), all societies classify work by gender. When a pattern appears in all societies, it is called a cultural universal. While the phenomenon of assigning work by gender is universal, its specifics are not. The same task is not assigned to either men or women worldwide. But the way each task’s associated gender is valued is notable. In Murdock’s examination of the division of labour among 324 societies around the world, he found that in nearly all cases the jobs assigned to men were given greater prestige (Murdock and White, 1969). Even if the job types were very similar and the differences slight, men’s work was still considered more vital.

Canadian society is also characterized by gender stratification. Evidence of gender stratification is especially keen within the economic realm. In Canada, women’s experience with wage labour includes unequal treatment in comparison to men in many respects:

- Women continue to do more of the unpaid labour in the household — meal preparation and cleanup, childcare, elderly care, household management, and shopping — even if they have a job outside the home. In 2010, women spent an average 50 hours a week looking after children compared to 24.4 hours a week for men, 13.8 hours a week doing household work compared to 8.3 hours for men, and, of those caring for elderly family members, 49% of women spent more than 10 hours a week caring for a senior compared to 25% for men (Statistics Canada, 2011). This double duty keeps working women in a subordinate role in the family structure and prevents them from achieving the salaries of men in the paid workforce (Hochschild and Machung, 1989).

- Women’s participation in the labour force has been increasing from 42% of women in 1976 to 58% of women in 2009 (Statistics Canada, 2011). Women now make up 48% of the total labour force (compared to 37% in 1976). They continue to dominate in “pink collar” occupations and part-time work, which are low paying, low status, often unskilled jobs that offer little possibility for advancement. In 2009, 67% of women still worked in traditionally “feminine” occupations like teaching, nursing, clerical, administrative or sales, and service jobs. 70% of part-time and 60% of minimum wage workers were women (Ferrao, 2010).

- Despite women making up nearly half (48%) of payroll employment, men vastly outnumber them in authoritative, powerful, and, therefore, high-earning jobs (Statistics Canada, 2011). Women’s income for full-year, full-time workers has remained at 72% of the income of men since 1992. This in part reflects the fact that women are more likely than men to work in part time or temporary employment. The comparison of average hourly wage is better: Women earned 83% of men’s average hourly wage in 2008, up from 76% in 1988 (Statistics Canada, 2011). However, as one report noted, if the gender gap in wages continues to close at the same glacial rate, women will not earn the same as men until the year 2240 (McInturff, 2013).

The reason for the gender gap in wages is fourfold. Firstly, there is gender discrimination in hiring and salary. Women and men are often not rewarded equally for the same work despite the fact discrimination on the basis of sex is unconstitutional in Canada. Secondly, as we noted above, men and women tend to be concentrated in different types of work which are not equally paid. Often because of choices made in high school and postsecondary education, women are limited to pink collar types of occupation. Thirdly, the unequal distribution of domestic duties, especially child and elder care, women are unable to work the same number of hours as men and experience disruptions in their career path. Fourthly, the work typically done by women is arbitrarily undervalued with respect to the work typically performed by men. It is certainly questionable that early childhood education occupations dominated by women involve less skill, less training, or less significance to society than many trades dominated by men, but there is a clear disparity in wages between these typically gender segregated types of occupation.

Beyond the economic sphere, there has been a long history of power relations based on gender in Canada. When looking to the past, it would appear that society has made great strides in terms of abolishing some of the most blatant forms of gender inequality (see timeline below) but the underlying effects of male dominance still permeate many aspects of society. The issue remains especially pertinent with regard to political representation. As elected representatives, the ratio of women to men in federal parliament and provincial legislatures is about 1 in 4, or 25% (McInturff, 2013).

- Before 1859 — Married women were not allowed to own or control property

- Before 1909 — Abducting a woman who was not an heiress was not a crime

- Before 1918 — Women were not permitted to vote (propertied women’s right to vote was taken away in New France in 1849)

- Before 1929 — Women were not legally considered “persons”

- Before 1953 — Employers could legally pay a woman less than a man for the same work

- Before 1969 — Women did not have the right to a safe and legal abortion (Nellie McClung Foundation, N.d.)

8.2.3 Is the Patriarchy Dead?

It is becoming more common to hear post-feminist arguments that in liberal democracies like Canada, the war against patriarchy (i.e., male rule) has more or less been won. The days in which women were not permitted to work or hold a credit card in their own name are over. Today women are working outside the home more than ever, they are narrowing the wage gap with men (albeit slowly), and they are surpassing men in getting university degrees. They are now as free as men to have a credit card and get into debt. These arguments are more complicated than the post-feminist slogan “patriarchy is dead” suggests, but it is clear that the question of gender inequality is more ambiguous than it once was.

| [Skip Table] | |||||||

| Year | Age Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 25 to 29 | 30 to 34 | 35 to 39 | 40 to 44 | 45 to 49 | 50 to 54 | |

| 1988 | 0.757 | 0.846 | 0.794 | 0.768 | 0.736 | 0.681 | 0.645 |

| 1993 | 0.794 | 0.905 | 0.886 | 0.772 | 0.762 | 0.700 | 0.709 |

| 1998 | 0.811 | 0.901 | 0.851 | 0.805 | 0.808 | 0.750 | 0.749 |

| 2003 | 0.825 | 0.920 | 0.868 | 0.843 | 0.804 | 0.768 | 0.771 |

| 2008 | 0.833 | 0.901 | 0.858 | 0.837 | 0.825 | 0.784 | 0.807 |

| Change: 1988 to 2008 | 0.076 | 0.056 | 0.064 | 0.068 | 0.089 | 0.103 | 0.162 |

Source Statistics Canada, 2011.

As noted above, women’s annual income (for full-time employees) remains at 72% of that earned by men. However, this figure is misleading because it does not take into account that men on average work 3.7 hours more a week than women (Statistics Canada, 2011, p. 167). Table 12.1 (above) compares men’s and women’s hourly wage and shows that between 1988 and 2008, the wage gap has narrowed for each of the age groups. On average, women went from earning 76% of men’s hourly wage to 83%. Young women ages 25 to 29 now earn 90% of young men’s hourly wage. As the Statistics Canada report says, “younger women are more likely to have high levels of education, work full-time, and be employed in different types of jobs than their older female counterparts” (Statistics Canada, 2011), which accounts for the difference between the age groups.

However, is this a good news story? First, the difference between the 72% figure (gender difference in annual income) and the 83% figure (gender difference in hourly wage) reveals, for reasons which are unclear from the statistics, that women are not working in occupations that pay as well or offer as many hours of work per week as men’s occupations. Second, the gender gap is closing in large part because men’s wages have remained flat or decreased. In particular, young men who worked traditionally in high paying manufacturing jobs have seen declines in union coverage and real wages (Drolet, 2011, p. 8). Third, even though young women have higher levels of education than young men, and even though they choose to work in higher paying jobs in education and health than previous generations of women, they still earn 10% less per hour than young men. That is still a substantial difference in wages that is unaccounted for. Fourth, the real problem is that although men and women increasingly begin their careers on equal footing, by mid-career, when workers are beginning to maximize their earning potential, women fall behind and continue to do so into retirement. Why?Making Connections: Sociological Research

8.2.4 Theoretical Perspectives on Gender

Sociological theories serve to guide the research process and offer a means for interpreting research data and explaining social phenomena. For example, a sociologist interested in gender stratification in education may study why middle-school girls are more likely than their male counterparts to fall behind grade-level expectations in math and science. Another scholar might investigate why women are underrepresented in political office, while another might examine how women members of Parliament are treated by their male counterparts in meetings.

Structural Functionalism

Structural functionalism provided one of the most important perspectives of sociological research in the 20th century and has been a major influence on research in the social sciences, including gender studies. Viewing the family as the most integral component of society, assumptions about gender roles within marriage assume a prominent place in this perspective.

Functionalists argue that gender roles were established well before the preindustrial era when men typically took care of responsibilities outside of the home, such as hunting, and women typically took care of the domestic responsibilities in or around the home. These roles were considered functional because women were often limited by the physical restraints of pregnancy and nursing, and unable to leave the home for long periods of time. Once established, these roles were passed on to subsequent generations since they served as an effective means of keeping the family system functioning properly.

When changes occurred in the social and economic climate of Canada during World War II, changes in the family structure also occurred. Many women had to assume the role of breadwinner (or modern hunter and gatherer) alongside their domestic role in order to stabilize a rapidly changing society. When the men returned from war and wanted to reclaim their jobs, society fell into a state of imbalance, as many women did not want to forfeit their wage-earning positions (Hawke, 2007).

Talcott Parsons (1943) argued that the contradiction between occupational roles and kinship roles of men and women in North America created tension or strain on individuals as they tried to adapt to the conflicting norms or requirements. The division of traditional middle-class gender roles within the family — the husband as breadwinner and wife as homemaker — was functional for him because the roles were complementary. They enabled a clear division of labour between spouses, which ensured that the ongoing functional needs of the family were being met. Within the North American kinship system, wives’ and husbands’ roles were equally valued according to Parsons. However, within the occupational system, only the husband’s role as breadwinner was valued. There was an “asymmetrical relation of the marriage pair to the occupational structure” (p. 191). Being barred from the occupational system meant that women had to find a functional equivalent to their husbands’ occupational status to demonstrate their “fundamental equality” to their husbands. As a result, Parson theorized that these tensions would lead women to become expressive specialists in order to claim prestige (e.g., showing “good taste” in appearance, household furnishings, literature, and music), while men would remain instrumental or technical specialists and become culturally narrow. He also proposed that the instability of women’s roles in this system would lead to excesses like neurosis, compulsive domesticity, garishness in taste, disproportionate attachment to community or club activities, and the “glamour girl” pattern: “the use of specifically feminine devices as an instrument of compulsive search for power and exclusive attention” (p. 194).

Critical Sociology

According to critical sociology, society is structured by relations of power and domination among social groups (e.g., women versus men) that determine access to scarce resources. When sociologists examine gender from this perspective, we can view men as the dominant group and women as the subordinate group. According to critical sociology, social problems and contradictions are created when dominant groups exploit or oppress subordinate groups. Consider the women’s suffrage movement or the debate over women’s “right to choose” their reproductive futures. It is difficult for women to rise above men, as dominant group members create the rules for success and opportunity in society (Farrington and Chertok, 1993).

Friedrich Engels, a German sociologist, studied family structure and gender roles in the 1880s. Engels suggested that the same owner-worker relationship seen in the labour force is also seen in the household, with women assuming the role of the proletariat. Women are therefore doubly exploited in capitalist society, both when they work outside the home and when they work within the home. This is due to women’s dependence on men for the attainment of wages, which is even worse for women who are entirely dependent upon their spouses for economic support. Contemporary critical sociologists suggest that when women become wage earners, they can gain power in the family structure and create more democratic arrangements in the home, although they may still carry the majority of the domestic burden, as noted earlier (Risman and Johnson-Sumerford, 1998).

Feminist Theory

Feminist theory is a type of critical sociology that examines inequalities in gender-related issues. It also uses the critical approach to examine the maintenance of gender roles and inequalities. Radical feminism, in particular, considers the role of the family in perpetuating male dominance. In patriarchal societies, men’s contributions are seen as more valuable than those of women. Women are essentially the property of men. Through the feminist struggles for women’s emancipation in post-feudal modern society, the property relationship has been formally eliminated. Nevertheless, women still tend to be relegated to the private sphere, where domestic roles define their primary status identity. Whereas men’s roles and primary status is defined by their activities in the public or occupational sphere.

As a result, women often perceive a disconnect between their personal experiences and the way the world is represented by society as a whole. Dorothy Smith referred to this phenomenon as bifurcated consciousness (Smith, 1987). There is a division between the directly lived, bodily experience of women’s worlds (e.g., their responsibilities for looking after children, aging parents, and household tasks) and the dominant, abstract, institutional world to which they must adapt (the work and administrative world of bureaucratic rules, documents, and cold, calculative reasoning). There are two modes of knowing, experiencing, and acting that are directly at odds with one another (Smith, 2008). Patriarchal perspectives and arrangements, widespread and taken for granted, are built into the relations of ruling. As a result, not only do women find it difficult to find their experiences acknowledged in the wider patriarchal culture, their viewpoints also tend to be silenced or marginalized to the point of being discredited or considered invalid.

Sanday’s study of the Indonesian Minangkabau (2004) revealed that in societies that some consider to be matriarchies (where women are the dominant group), women and men tend to work cooperatively rather than competitively, regardless of whether a job is considered feminine by North American standards. The men, however, do not experience the sense of bifurcated consciousness under this social structure that modern Canadian females encounter (Sanday, 2004).

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism aims to understand human behaviour by analyzing the critical role of symbols in human interaction. This is certainly relevant to the discussion of masculinity and femininity. Imagine that you walk into a bank, hoping to get a small loan for school, a home, or a small business venture. If you meet with a male loan officer, you may state your case logically by listing all of the hard numbers that make you a qualified applicant as a means of appealing to the analytical characteristics associated with masculinity. If you meet with a female loan officer, you may make an emotional appeal by stating your good intentions as a means of appealing to the caring characteristics associated with femininity.

Because the meanings attached to symbols are socially created and not natural, and fluid, not static, we act and react to symbols based on the current assigned meaning. The word gay, for example, once meant “cheerful,” but by the 1960s it carried the primary meaning of “homosexual.” In transition, it was even known to mean “careless” or “bright and showing” (Oxford American Dictionary, 2010). Furthermore, the word gay (as it refers to a homosexual) carried a somewhat negative and unfavourable meaning 50 years ago, but has since gained more neutral and even positive connotations.

These shifts in symbolic meaning apply to family structure as well. In 1976, when only 27.6% of married women with preschool-aged children were part of the paid workforce, a working mother was still considered an anomaly and there was a general view that women who worked were “selfish” and not good mothers. Today, a majority of women with preschool-aged children are part of the paid workforce (66.5%), and a working mother is viewed as more normal (Statistics Canada, 2011).

Sociologist Charles H. Cooley’s concept of the “looking-glass self” (1902) can also be applied to interactionist gender studies. Cooley suggests that one’s determination of self is based mainly on the view of society (for instance, if society perceives a man as masculine, then that man will perceive himself as masculine). When people perform tasks or possess characteristics based on the gender role assigned to them, they are said to be doing gender (West and Zimmerman, 1987). Whether we are expressing our masculinity or femininity, West and Zimmerman argue, we are always “doing gender.” Thus, gender is something we do or perform, not something we are.

8.3. Sex and Sexuality

8.3.1 Sexual Attitudes and Practices

In the area of sexuality, sociologists focus their attention on sexual attitudes and practices, not on physiology or anatomy. As noted above, sexuality is viewed as a person’s capacity for sexual feelings and the orientation of those feelings. Studying sexual attitudes and practices is a particularly interesting field of sociology because sexual behaviour is a cultural universal. Throughout time and place, the vast majority of human beings have participated in sexual relationships (Broude, 2003). Each society, however, interprets sexuality and sexual activity in different ways. Many societies around the world have different attitudes about premarital sex, the age of sexual consent, homosexuality, masturbation, and other sexual behaviours that are not consistent with universally cultural norms (Widmer, Treas, and Newcomb, 1998). At the same time, sociologists have learned that certain norms (like the disapproval of incest) are shared among most societies. Likewise, societies generally have norms that reinforce their accepted social system of sexuality.

What is considered “normal” in terms of sexual behaviour is based on the mores and values of the society. Societies that value monogamy, for example, would likely oppose extramarital sex. Individuals are socialized to sexual attitudes by their family, education system, peers, media, and religion. Historically, religion has been the greatest influence on sexual behaviour in most societies, but in more recent years, peers and the media have emerged as two of the strongest influences — particularly with North American teens (Potard, Courtois, and Rusch, 2008). Let us take a closer look at sexual attitudes in Canada and around the world.

Sexuality around the World

Cross-national research on sexual attitudes in industrialized nations reveals that normative standards differ across the world. For example, several studies have shown that Scandinavian students are more tolerant of premarital sex than are North American students (Grose, 2007). A study of 37 countries reported that non-Western societies — like China, Iran, and India — valued chastity highly in a potential mate, while Western European countries — such as France, the Netherlands, and Sweden — placed little value on prior sexual experiences (Buss, 1989).

Even among Western cultures, attitudes can differ. For example, according to a 33,590-person survey across 24 countries, 89% of Swedes responded that there is nothing wrong with premarital sex, while only 42% of Irish responded this way. From the same study, 93% of Filipinos responded that sex before age 16 is always wrong or almost always wrong, while only 75% of Russians responded this way (Widmer, Treas, and Newcomb, 1998). Sexual attitudes can also vary within a country. For instance, 45% of Spaniards responded that homosexuality is always wrong, while 42% responded that it is never wrong; only 13% responded somewhere in the middle (Widmer, Treas, and Newcomb, 1998).

Of industrialized nations, Sweden is thought to be the most liberal when it comes to attitudes about sex, including sexual practices and sexual openness. The country has very few regulations on sexual images in the media, and sex education, which starts around age six, is a compulsory part of Swedish school curricula. Sweden’s permissive approach to sex has helped the country avoid some of the major social problems associated with sex. For example, rates of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease are among the world’s lowest (Grose, 2007). It would appear that Sweden is a model for the benefits of sexual freedom and frankness. However, implementing Swedish ideals and policies regarding sexuality in other, more politically conservative, nations would likely be met with resistance.

Sexuality in Canada

Canada is often considered to be conservative and “stodgy” compared to the United States, which prides itself on being the land of the “free.” However, the United States is much more restrictive when it comes to its citizens’ general attitudes about sex. In the 1998 international survey noted above, 12% of Canadians stated that premarital sex is always wrong, compared to 29% of Americans. The average among the 24 countries surveyed on this question was 17%. Compared to 71% of Americans, 55% of Canadians condemned sex before the age of 16 years, 68% compared to 80% (U.S.) condemned extramarital sex, and 39% compared to 70% (U.S.) condemned homosexuality (Widmer, Treas, and Newcomb, 1998). A 2013 international study showed that to the question “Should society accept homosexuality?” 80% of Canadians said “yes” compared to 14% who said “no.” Whereas, in the United States 60% said “yes” and 33% said “no” (Pew Research Center, 2013).

North American culture is particularly restrictive in its attitudes about sex when it comes to women and sexuality. It is widely believed that men are more sexual than women. In fact, there is a popular notion that men think about sex every seven seconds. Research, however, suggests that men think about sex an average of 19 times per day, compared to 10 times per day for women (Fisher, Moore, and Pittenger, 2011).

The belief that men have — or have the right to — more sexual urges than women creates a double standard. Ira Reiss, a pioneer researcher in the field of sexual studies, defined the double standard as prohibiting premarital sexual intercourse for women but allowing it for men (Reiss, 1960). This standard has evolved into allowing women to engage in premarital sex only within committed love relationships, but allowing men to engage in sexual relationships with as many partners as they wish without condition (Milhausen and Herold, 1999). Due to this double standard, a woman is likely to have fewer sexual partners in her lifetime than a man. According to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2011 survey, the average 35-year-old woman has had three opposite-sex sexual partners while the average 35-year-old man has had twice as many (Centers for Disease Control, 2011). In a study of 1,479 Canadians over the age of 18, men had had an average of 11.25 sexual partners over their lifetime whereas women had an average of 4 (Fischtein, Herold, and Desmarais, 2007).

One of the principal insights of contemporary sociology is that a focus on the social construction of different social experiences and problems leads to alternative ways of understanding them and responding to them. The sociologist often confronts a legacy of entrenched beliefs concerning innate biological disposition, or the individual psychopathology of persons who are considered abnormal. The sexual or gender “deviant” is a primary example. However, as Ian Hacking (2006) observes, even when these beliefs about kinds of persons are products of objective scientific classification, the institutional context of science and expert knowledge is not independent of societal norms, beliefs, and practices. The process of classifying kinds of people is a social process that Hacking calls “making up people” and Howard Becker (1963) calls “labeling.”

A homosexual was first defined as a kind of person in the 19th century: the sexual “invert.” This definition was “scientific,” but in no way independent of the cultural norms and prejudices of the times. The idea that homosexuals were characterized by an internal, deviant “inversion” of sexual instincts depended on the new scientific disciplines of biology and psychiatry (Foucault, 1980). The homosexual’s deviance was defined first by the idea that heterosexuality was biologically natural (and therefore “normal”) and second by the idea that, psychologically, sexual preference defined every aspect of the personality. Within the emerging field of psychiatry, it was possible to speak of an inverted personality because a lesbian woman who did not play the “proper” passive sexual role of her gender was masculine. A gay man who did not play his “proper” active sexual role was effeminate. After centuries during which an individual’s sexual preference was largely a matter of public indifference, in the 19th century, the problem of sexuality suddenly emerged as a biological, social, psychological, and moral concern.

The new definitions of homosexuality and sexual inversion led to a series of social anxieties that ranged from a threat to the propagation of the human species, to the perceived need to “correct” sexual deviation through psychiatric and medical treatments. The powerful normative constraints that emerged based largely on the 19th century scientific distinction between natural and unnatural forms of sexuality lead to the legacy of closeted sexuality and homophobic violence that remains to this day. Nevertheless, they depend on the concept of the homosexual as a specific kind of person.