7 Module 7: Social Identities: Class, Status and Power

Learning Objectives

- Elaborate the concept of social inequality into its component parts: social difference, social stratification and social distributions of wealth, income, power and status.

- Define the difference between equality of opportunity and equality of condition.

- Explain why there is a decline in most Canadian’s identification with a social class identity.

- Explain why the ideology of the middle class and identification with the middle class is a problem for average Canadians.

- Discuss significant similarities and differences among Marx, Weber and Durkheim relative to their definitions of social class and the consequences of class identification for social participation.

- Identify and describe cultural markers that are used to express class identity in contemporary society.

- Describe and discuss how a revitalization of discussions of social class identification and expression may have positive implications for efforts to achieve social justice in society.

7.0 Introduction to Class Identity and Classism

When he died in 2008, Ted Rogers Jr., then CEO of Rogers Communications, was the fifth-wealthiest individual in Canada, holding assets worth $5.7 billion. In his autobiography (2008) he credited his success to a willingness to take risks, work hard, bend the rules, be on the constant look-out for opportunities, and be dedicated to building the business. In many respects, he saw himself as a self-made billionaire who started from scratch, seized opportunities, and created a business through his own initiative.

The story of Ted Rogers is not exactly a rags to riches one, however. His grandfather, Albert Rogers, was a director of Imperial Oil (Esso) and his father, Ted Sr., became wealthy when he invented an alternating current vacuum tube for radios in 1925. Ted Rogers Sr. went from this invention to manufacturing radios, owning a radio station, and acquiring a licence for TV broadcasting.

However, Ted Sr. died when Ted Jr. was five years old, and the family businesses were sold. His mother took Ted Jr. aside when he was eight and told him, “Ted, your business is to get the family name back” (Rogers, 2008). The family was still wealthy enough to send him to Upper Canada College, the famous private school that also educated the children from the Black, Eaton, Thompson, and Weston families. Ted seized the opportunity at Upper Canada to make money as a bookie, taking bets on horse racing from the other students. Then he attended Osgoode Hall Law School, where reportedly his secretary went to classes and took notes for him. He bought an early FM radio station when he was still in university and started in cable TV in the mid-1960s. By the time of his death, Rogers Communications was worth $25 billion. At that time just three families, the Rogers, Shaws, and Péladeaus, owned much of the cable service in Canada.

At the other end of the spectrum are Aboriginal gang members in the Saskatchewan Correctional Centre. In 2010 the CBC program The Current aired a report about several young Aboriginal men who were serving time in prison in Saskatchewan for gang-related activities (CBC, 2010). They all expressed desires to be able to deal with their drug addiction issues, return to their families, and assume their responsibilities when their sentences were complete. They wanted to have their own places with nice things in them. However, according to the CBC report, 80% of the prison population in the Saskatchewan Correctional Centre were Aboriginal and 20% of those were gang members. This is consistent with national statistics on Aboriginal incarceration which showed that in 2010–2011, the Aboriginal incarceration rate was 10 times higher than for the non-Aboriginal population. While Aboriginal people account for about 4% of the Canadian population, in 2013 they made up 23.2% of the federal penitentiary population. In 2001 they made up only 17% of the penitentiary population. Aboriginal overrepresentation in prisons has continued to grow substantially (Office of the Correctional Investigator, 2013). The outcomes of Aboriginal incarceration are also bleak. The federal Office of the Correctional Investigator summarized the situation as follows. Aboriginal inmates are:

- Routinely classified as higher risk and higher need in categories such as employment, community reintegration, and family supports.

- Released later in their sentence (lower parole grant rates); most leave prison at Statutory Release or Warrant Expiry dates.

- Overrepresented in segregation and maximum security populations.

- Disproportionately involved in use-of-force interventions and incidents of prison self-injury.

- More likely to return to prison on revocation of parole, often for administrative reasons, not criminal violations (2013).

The federal report notes that “the high rate of incarceration for Aboriginal peoples has been linked to systemic discrimination and attitudes based on racial or cultural prejudice, as well as economic and social disadvantage, substance abuse, and intergenerational loss, violence and trauma” (2013).

This is clearly a case in which the situation of the incarcerated inmates interviewed on the CBC program has been structured by historical social patterns and power relationships that confront Aboriginal people in Canada generally. How do we understand it at the individual level, however — at the level of personal decision making and individual responsibilities? One young inmate described how, at the age of 13, he began to hang around with his cousins who were part of a gang. He had not grown up with “the best life”; he had family members suffering from addiction issues and traumas. The appeal of what appeared as a fast and exciting lifestyle — the sense of freedom and of being able to make one’s own life, instead of enduring poverty — was compelling. He began to earn money by “running dope” but also began to develop addictions. He was expelled from school for recruiting gang members. The only job he ever had was selling drugs. The circumstances in which he and the other inmates had entered the gang life, and the difficulties getting out of it they knew awaited them when they left prison, reflect a set of decision-making parameters fundamentally different than those facing most non-Aboriginal people in Canada.

The CBC program noted that 85 percent of the inmates in the prison were of Aboriginal descent, half of whom were involved in Aboriginal gangs. Moreover the statistical profile of Aboriginal youth in Saskatchewan is grim, with Aboriginal people making up the highest number of high school dropouts, domestic abuse victims, drug dependencies, and child poverty backgrounds. In some respects the Aboriginal gang members interviewed were like Ted Rogers in that they were willing to seize opportunities, take risks, bend rules, and apply themselves to their vocations. They too aspired to getting the money that would give them the freedom to make their own lives.

How do we make sense of these divergent stories? Canada is supposed to be a country in which individuals can work hard to get ahead. It is an “open” society. There are no formal or explicit class, gender, racial, ethnic, geographical, or other boundaries that prevent people from rising to the top. People are free to make choices. But does this adequately explain the difference in life chances that divide the fortunes of the Aboriginal youth from those of the Rogers family?

The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002) defined ones habitus as the deeply seated schemas, habits, feelings, dispositions, and forms of know-how that people hold due to their specific social backgrounds, cultures, and life experiences (1990). Bourdieu referred to it as ones “feel for the game,” to use a sports metaphor. Choices are perhaps always “free” in some formal sense, but they are also always situated within one’s habitus. The Aboriginal gang members display a certain amount of street smarts that enable them to survive and successfully navigate their world. Street smarts define their habitus and exercise a profound influence over the range of options that are available for them to consider — the neighborhoods they know to avoid, the body languages that signal danger, the values of illicit goods, the motives of different street actors, the routines of police interactions, etc. The habitus affects both the options to conform to the group they identify with or deviate from it. Ted Rogers occupied a different habitus which established a fundamentally different set of options for him in his life path. How are the different lifeworlds or habitus distributed in society so that some reinforce patterns of deprivation while others provide the basis for access to wealth and power?

As Bourdieu pointed out, habitus is so deeply ingrained that we take its reality as natural rather than as a product of social circumstances. This has the unfortunate effect of justifying social inequalites based in the belief that the Ted Rogers of the world were naturally gifted and predisposed for success when in fact it is success itself that is “predisposed” by underlying structures of power and privilege.

7.1. What Is Social Inequality?

Sociologists use the term social inequality to describe the unequal distribution of valued resources, rewards, and positions in a society. Key to the concept is the notion of social differentiation. Social characteristics — differences, identities, and roles — are used to differentiate people and divide them into different categories, which have implications for social inequality. Social differentiation by itself does not necessarily imply a division of individuals into a hierarchy of rank, privilege, and power. However, when a social category like class, occupation, gender, or race puts people in a position in which they can claim a greater share of resources or services, then social differentiation becomes the basis of social inequality.

The term social stratification refers to an institutionalized system of social inequality. It refers to a situation in which the divisions and relationships of social inequality have solidified into a system that determines who gets what, when, and why. You may remember the word “stratification” from geology class. The distinct horizontal layers found in rock, called “strata,” are a good way to visualize social structure. Society’s layers are made of people, and society’s resources are distributed unevenly throughout the layers. The people who have more resources represent the top layer of the social structure of stratification. Other groups of people, with progressively fewer and fewer resources, represent the lower layers of our society. Social stratification assigns people to socioeconomic strata based on factors like wealth, income, race, education, and power. The question for sociologists is how systems of stratification come to be formed. What is the basis of systematic social inequality in society?

In Canada, the dominant ideological presumption about social inequality is that everyone has an equal chance at success. This is the belief in equality of opportunity, which can be contrasted with the concept of equality of condition. Equality of condition is the situation in which everyone in a society has a similar level of wealth, status, and power. Although degrees of equality of condition vary markedly in modern societies, it is clear that even the most egalitarian societies today have considerable degrees of inequality of condition. Equality of opportunity, on the other hand, is the idea that everyone has an equal possibility of becoming successful. It exists when people have the same chance to pursue economic or social rewards. This is often seen as a function of equal access to education, meritocracy (where individual merit determines social standing), and formal or informal measures to eliminate social discrimination. Ultimately, equality of opportunity means that inequalities of condition are not so great that they greatly hamper a person’s life chances. Whether Canada is a society characterized by equality of opportunity or not is a subject of considerable sociological debate.

To a certain extent, Ted Rogers’ story illustrates the belief in equality of opportunity. His personal narrative is one in which hard work and talent — not inherent privilege, birthright, prejudicial treatment, or societal values — determined his social rank. This emphasis on self-effort is based on the belief that people individually control their own social standing, which is a key piece in the idea of equality of opportunity. Most people connect inequalities of wealth, status, and power to the individual characteristics of those who succeed or fail. The story of the Aboriginal gang members, although it is also a story of personal choices, casts that belief into doubt. It is clear that the type of choices available to the Aboriginal gang members are of a different range and quality than those available to the Rogers family. The available choices are a product of habitus.

Sociologists recognize that social stratification is a society-wide system that makes inequalities apparent. While there are always inequalities between individuals, sociologists are interested in larger social patterns. Social inequality is not about individual inequalities, but about systematic inequalities based on group membership, class, gender, ethnicity, and other variables that structure access to rewards and status. In other words, sociologists are interested in examining the structural conditions of social inequality. There are of course differences in individuals’ abilities and talents that will affect their life chances. The larger question, however, is how inequality becomes systematically structured in economic, social, and political life. In terms of individual ability: Who gets the opportunities to develop their abilities and talents, and who does not? Where does “ability” or “talent” come from? As we live in a society that emphasizes the individual — i.e., individual effort, individual morality, individual choice, individual responsibility, individual talent, etc. — it is often difficult to see the way in which life chances are socially structured.

Factors that define stratification vary in different societies. In most modern societies, stratification is often indicated by differences in wealth, the net value of money and assets a person has, and income, a person’s wages, salary, or investment dividends. It can also be defined by differences in power (how many people a person must take orders from versus how many people a person can give orders to) and status (the degree of honour or prestige one has in the eyes of others). These four factors create a complex amalgam that defines individuals’ social standing within a hierarchy.

Usually the four factors coincide, as in the case of corporate CEOs, like Ted Rogers, at the top of the hierarchy—wealthy, powerful, and prestigious — and the Aboriginal offenders at the bottom — poor, powerless, and abject. Sociologists use the term status consistency to describe the consistency of an individual’s rank across these factors. However, we can also think of someone like the Canadian prime minister who ranks high in power, but with a salary of approximately $320,000 earns much less than comparable executives in the private sector (albeit eight times the average Canadian salary). The prime minister’s status or prestige also rises and falls with the vagaries of politics. The Nam-Boyd scale of status ranks politicians at 66/100, the same status as cable TV technicians (Boyd, 2008). There is status inconsistency in the prime minister’s position. Similarly, teachers often have high levels of education, which give them high status (92/100 according to the Nam-Boyd scale), but they receive relatively low pay. Many believe that teaching is a noble profession, so teachers should do their jobs for love of their profession and the good of their students, not for money. Yet no successful executive or entrepreneur would embrace that attitude in the business world, where profits are valued as a driving force. Cultural attitudes and beliefs like these support and perpetuate social inequalities.

While Canadians are generally aware of the existence of social inequality in Canada and of the fact that gaps between upper and lower economic strata have widened in recent decades, there continues to be a high level of ambivalence among Canadians when it comes to the meaning of social class, class identification and class consciousness. In fact, a majority of Canadians, when asked to identify their social class location will respond ‘middle’, with little objective justification or explanation to account for their identification with that strata.

For additional insight into the disappearing recognition of class location and influence of class consciousness in the social construction of Canadian identity, attention is turned to a series of essays written by a social activist, Sandy Cameron.

7.2. Class, Class Consciousness and Class Relationships within Classical Sociology

7.2.1. Marx and the History of Class Struggle

For Marx, what we do defines who we are. What it is to be “human” is defined by the capacity we have as a species to creatively transform the world in which we live to meet our needs for survival. Humanity at its core is Homo faber (“Man the Creator”). In historical terms, in spite of the persistent nature of one class dominating another, the element of humanity as creator existed. There was at least some connection between the worker and the product, augmented by the natural conditions of seasons and the rising and setting of the sun, such as we see in an agricultural society. But with the bourgeois revolution and the rise of industry and capitalism, workers now worked for wages alone. The essential elements of creativity and self-affirmation in the free disposition of their labour was replaced by compulsion. The relationship of workers to their efforts was no longer of a human nature, but based purely on animal needs. As Marx put it, the worker “only feels himself freely active in his animal functions of eating, drinking, and procreating, at most also in his dwelling and dress, and feels himself an animal in his human functions” (1932/1977).

Marx described the economic conditions of production under capitalism in terms of alienation. Alienation refers to the condition in which the individual is isolated and divorced from his or her society, work, or the sense of self and common humanity. Marx defined four specific types of alienation that arose with the development of wage labour under capitalism.

Alienation from the product of one’s labour. An industrial worker does not have the opportunity to relate to the product he or she is labouring on. The worker produces commodities, but at the end of the day the commodities not only belong to the capitalist, but serve to enrich the capitalist at the worker’s expense. In Marx’s language, the worker relates to the product of his or her labour “as an alien object that has power over him [or her]” (1932/1977). Workers do not care if they are making watches or cars; they care only that their jobs exist. In the same way, workers may not even know or care what products they are contributing to. A worker on a Ford assembly line may spend all day installing windows on car doors without ever seeing the rest of the car. A cannery worker can spend a lifetime cleaning fish without ever knowing what product they are used for.

Alienation from the process of one’s labour. Workers do not control the conditions of their jobs because they do not own the means of production. If someone is hired to work in a fast food restaurant, that person is expected to make the food exactly the way they are taught. All ingredients must be combined in a particular order and in a particular quantity; there is no room for creativity or change. An employee at Burger King cannot decide to change the spices used on the fries in the same way that an employee on a Ford assembly line cannot decide to place a car’s headlights in a different position. Everything is decided by the owners who then dictate orders to the workers. The workers relate to their own labour as an activity that does not belong to them.

Alienation from others. Workers compete, rather than cooperate. Employees vie for time slots, bonuses, and job security. Different industries and different geographical regions compete for investment. Even when a worker clocks out at night and goes home, the competition does not end. As Marx commented in The Communist Manifesto, “No sooner is the exploitation of the labourer by the manufacturer, so far at an end, that he receives his wages in cash, than he is set upon by the other portion of the bourgeoisie, the landlord, the shopkeeper, the pawnbroker” (1848/1977).

Alienation from one’s humanity. A final outcome of industrialization is a loss of connectivity between a worker and what makes them truly human. Humanity is defined for Marx by “conscious life-activity,” but under conditions of wage labour this is taken not as an end in itself — only a means of satisfying the most base, animal-like needs. The “species being” (i.e., conscious activity) is only confirmed when individuals can create and produce freely, not simply when they work to reproduce their existence and satisfy immediate needs like animals.

Taken as a whole, then, alienation in modern society means that individuals have no control over their lives. There is nothing that ties workers to their occupations. Instead of being able to take pride in an identity such as being a watchmaker, automobile builder, or chef, a person is simply a cog in the machine. Even in feudal societies, people controlled the manner of their labour as to when and how it was carried out. But why, then, does the modern working class not rise up and rebel?

In response to this problem, Marx developed the concept of false consciousness. False consciousness is a condition in which the beliefs, ideals, or ideology of a person are not in the person’s own best interest. In fact, it is the ideology of the dominant class (here, the bourgeoisie capitalists) that is imposed upon the proletariat. Ideas such as the emphasis of competition over cooperation, of hard work being its own reward, of individuals as being the isolated masters of their own fortunes and ruins, etc. clearly benefit the owners of industry. Therefore, to the degree that workers live in a state of false consciousness, they are less likely to question their place in society and assume individual responsibility for existing conditions.

Like other elements of the superstructure, “consciousness,” is a product of the underlying economic; Marx proposed that the workers’ false consciousness would eventually be replaced with class consciousness — the awareness of their actual material and political interests as members of a unified class. In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels wrote,

The weapons with which the bourgeoisie felled feudalism to the ground are now turned against the bourgeoisie itself. But not only has the bourgeoisie forged the weapons that bring death to itself; it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons — the modern working class — the proletarians (1848/1977).

Capitalism developed the industrial means by which the problems of economic scarcity could be resolved and, at the same time, intensified the conditions of exploitation due to competition for markets and profits. Thus emerged the conditions for a successful working class revolution. Instead of existing as an unconscious “class in itself,” the proletariat would become a “class for itself” and act collectively to produce social change (Marx and Engels, 1848/1977). Instead of just being an inert strata of society, the class could become an advocate for social improvements. Only once society entered this state of political consciousness would it be ready for a social revolution. Indeed, Marx predicted that this would be the ultimate outcome and collapse of capitalism.

7.1.2. Weber and the rise of Modern Subjectivity

If Marx’s analysis is central to the sociological understanding of the structures that emerged with the rise of capitalism, Max Weber is a central figure in the sociological understanding of the effects of capitalism on modern subjectivity: how our basic sense of who we are and what we might aspire to has been defined by the culture and belief system of capitalism. The key work here is Weber’s Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905/1958) in which he lays out the characteristics of the modern ethos of work. Why do we feel compelled to work so hard?

An ethic or ethos refers to a way of life or a way of conducting oneself in life. For Weber, the Protestant work ethic was at the core of the modern ethos. It prescribes a mode of self-conduct in which discipline, work, accumulation of wealth, self-restraint, postponement of enjoyment, and sobriety are the focus of an individual life.

In Weber’s analysis, the ethic was indebted to the religious beliefs and practices of certain Protestant sects like the Lutherans, Calvinists, and Baptists who emerged with the Protestant Reformation (1517–1648). The Protestant theologian Richard Baxter proclaimed that the individual was “called” to their occupation by God, and therefore, they had a duty to “work hard in their calling.” “He who will not work shall not eat” (Baxter, as cited in Weber, 1958). This ethic subsequently worked its way into many of the famous dictums popularized by the American Benjamin Franklin, like “time is money” and “a penny saved is two pence dear” (i.e., “a penny saved is a penny earned”).

In Weber’s estimation, the Protestant ethic was fundamentally important to the emergence of capitalism, and a basic answer to the question of how and why it could emerge. Throughout the period of feudalism and the domination of the Catholic Church, an ethic of poverty and non-materialist values was central to the subjectivity and worldview of the Christian population. From the earliest desert monks and followers of St. Anthony to the great Vatican orders of the Franciscans and Dominicans, the image of Jesus was of a son of God who renounced wealth, possessions, and the material world. “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God” (Mark 10:25). We are of course well aware of the hypocrisy with which these beliefs were often practiced, but even in these cases, wealth was regarded in a different manner prior to the modern era. One worked only as much as was required. As Thomas Aquinas put it “labour [is] only necessary … for the maintenance of individual and community. Where this end is achieved, the precept ceases to have any meaning” (Aquinas, as cited in Weber, 1958). Wealth was not “put to work” in the form of a gradual return on investments as it is under capitalism. How was this medieval belief system reversed? How did capitalism become possible?

The key for Weber was the Protestant sects’ doctrines of predestination, the idea of the personal calling, and the individual’s direct, unmediated relationship to God. In the practice of the Protestant sects, no intermediary or priest interpreted God’s will or granted absolution. God’s will was essentially unknown. The individual could only be recognized as one of the predestined “elect” — one of the saved — through outward signs of grace: through the continuous display of moral self-discipline and, significantly, through the accumulation of earthly rewards that tangibly demonstrated God’s favour. In the absence of any way to know with certainty whether one was destined for salvation, the accumulation of wealth and material success became a sign of spiritual grace rather than a sign of sinful, earthly concerns. For the individual, material success assuaged the existential anxiety concerning the salvation of his or her soul. For the community, material success conferred status.

Weber argues that gradually the practice of working hard in one’s calling lost its religious focus, and the ethic of “sober bourgeois capitalism” (Weber, 1905/1958) became grounded in discipline alone: work and self-improvement for their own sake. This discipline of course produces the rational, predictable, and industrious personality type ideally suited for the capitalist economy. For Weber, the consequence of this, however, is that the modern individual feels compelled to work hard and to live a highly methodical, efficient, and disciplined life to demonstrate their self-worth to themselves as much as anyone. The original goal of all this activity — namely religious salvation — no longer exists. It is a highly rational conduct of life in terms of how one lives, but is simultaneously irrational in terms of why one lives. Weber calls this conundrum of modernity the iron cage. Life in modern society is ordered on the basis of efficiency, rationality, and predictability, and other inefficient or traditional modes of organization are eliminated. Once we are locked into the “technical and economic conditions of machine production” it is difficult to get out or to imagine another way of living, despite the fact that one is renouncing all of the qualities that make life worth living: spending time with friends and family, enjoying the pleasures of sensual and aesthetic life, and/or finding a deeper meaning or purpose of existence. We might be obliged to stay in this iron cage “until the last ton of fossilized coal is burnt” (Weber, 1905/1958).

7.1.3. Durkheim and the rise of Moral Individualism

Émile Durkheim’s (1858-1917) key focus in studying modern society was to understand the conditions under which social and moral cohesion could be reestablished. He observed that European societies of the 19th century had undergone an unprecedented and fractious period of social change that threatened to dissolve society altogether. In his book The Division of Labour in Society (1893/1960), Durkheim argued that as modern societies grew more populated, more complex, and more difficult to regulate, the underlying basis of solidarity or unity within the social order needed to evolve. His primary concern was that the cultural glue that held society together was failing, and that the divisions between people were becoming more conflictual and unmanageable. Therefore Durkheim developed his school of sociology to explain the principles of cohesiveness of societies (i.e., their forms of social solidarity) and how they change and survive over time. He thereby addressed one of the fundamental sociological questions: why do societies hold together rather than fall apart?

Two central components of social solidarity in traditional, premodern societies were the common collective conscience — the communal beliefs, morals, and attitudes of a society shared by all — and high levels of social integration — the strength of ties that people have to their social groups. These societies were held together because most people performed similar tasks and shared values, language, and symbols. There was a low division of labour, a common religious system of social beliefs, and a low degree of individual autonomy. Society was held together on the basis of mechanical solidarity: a minimal division of labour and a shared collective consciousness with harsh punishment for deviation from the norms. Such societies permitted a low degree of individual autonomy. Essentially there was no distinction between the individual conscience and the collective conscience.

Societies with mechanical solidarity act in a mechanical fashion; things are done mostly because they have always been done that way. If anyone violated the collective conscience embodied in laws and taboos, punishment was swift and retributive. This type of thinking was common in preindustrial societies where strong bonds of kinship and a low division of labour created shared morals and values among people, such as among the feudal serfs. When people tend to do the same type of work, Durkheim argued, they tend to think and act alike.

Modern societies, according to Durkheim, were more complex. Collective consciousness was increasingly weak in individuals and the ties of social integration that bound them to others were increasingly few. Modern societies were characterized by an increasing diversity of experience and an increasing division of people into different occupations and specializations. They shared less and less commonalities that could bind them together. However, as Durkheim observed, their ability to carry out their specific functions depended upon others being able to carry out theirs. Modern society was increasingly held together on the basis of a division of labour or organic solidarity: a complex system of interrelated parts, working together to maintain stability, i.e., like an organism (Durkheim, 1893/1960).

According to his theory, as the roles individuals in the division of labour become more specialized and unique, and people increasingly have less in common with one another, they also become increasingly interdependent on one another. Even though there is an increased level of individual autonomy — the development of unique personalities and the opportunity to pursue individualized interests — society has a tendency to cohere because everyone depends on everyone else. The academic relies on the mechanic for the specialized skills required to fix his or her car, the mechanic sends his or her children to university to learn from the academic, and both rely on the baker to provide them with bread for their morning toast. Each member of society relies on the others. In premodern societies, the structures like religious practice that produce shared consciousness and harsh retribution for transgressions function to maintain the solidarity of society as a whole; whereas in modern societies, the occupational structure and its complex division of labour function to maintain solidarity through the creation of mutual interdependence.

While the transition from mechanical to organic solidarity is, in the long run, advantageous for a society, Durkheim noted that it creates periods of chaos and “normlessness.” One of the outcomes of the transition is social anomie. Anomie — literally, “without norms” — is a situation in which society no longer has the support of a firm collective consciousness. There are no clear norms or values to guide and regulate behaviour. Anomie was associated with the rise of industrial society, which removed ties to the land and shared labour; the rise of individualism, which removed limits on what individuals could desire; and the rise of secularism, which removed ritual or symbolic foci and traditional modes of moral regulation. During times of war or rapid economic development, the normative basis of society was also challenged. People isolated in their specialized tasks tend to become alienated from one another and from a sense of collective conscience. However, Durkheim felt that as societies reach an advanced stage of organic solidarity, they avoid anomie by redeveloping a set of shared norms. According to Durkheim, once a society achieves organic solidarity, it has finished its development.

While each of the classical sociological thinkers discussed here presented somewhat different conceptualizations of social class and the consequences of class for individuals and society, all viewed social class as a central feature of individual and social existence as well as the future of human society. However, as illustrated in the essays by activist, Sandy Cameron, discussion of social class and to some extent, explicit identification with traditional notions of social class have been significantly marginalized, if not relegated to the status of taboo in popular and sociological discourse. Does this mean that social class is no longer a marker and factor in collective actions to achieve social justice in society, or might there be other factors to consider?

7.3 Social Class Identities in Canada

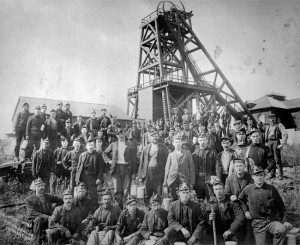

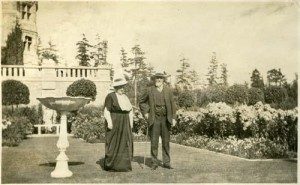

|

|

Although Canadian’s tend to self identify with a rather ambiguous middle class identity and political, business and academic leaders encourage this somewhat ‘classless’ identity, does a person’s appearance and manner indicate class? Can you tell a person’s education level based on clothing? Do you know a person’s income by the car one drives? There was a time in Canada when people’s class was more visibly apparent. In some countries, like the United Kingdom, class differences can still be gauged by differences in schooling, lifestyle, and even accent. In Canada, however, it is harder to determine class from outward appearances.

For sociologists, too, categorizing class is a fluid science. The chief division in the discipline is between Marxist and Weberian approaches to social class (Abercrombie & Urry, 1983). Marx’s analysis, as we saw earlier in this module, emphasized a materialist approach to the underlying structures of the capitalist economy. Marx’s definition of social class rested essentially on one variable: a group’s relation to the means of production (ownership or non-ownership of productive property or capital). In Marxist class analysis there are, therefore, two dominant classes in capitalism — the working class and the owning class — and any divisions within the classes based on occupation, status, education, etc. are less important than the tendency toward the increasing separation and polarization of these classes.

Weber defined social class slightly differently, as the “life chances” or opportunities to acquire rewards one shares in common with others by virtue of one’s possession of property, goods, or opportunities for income (1969). Owning property/capital or not owning property/capital is still the basic variable that defines a person’s class situation or life chances. However, class is defined with respect to markets rather than the process of production. It is the value of one’s products or skills on the labour market that determines whether one has greater or lesser life chances. This leads to a hierarchical class schema with many gradations. A surgeon who works in a hospital is a member of the working class in Marx’s model, just like cable TV technicians, for example, because he or she works for a wage or salary. Nevertheless the skill the surgeon sells is valued much more highly in the labour market than that of cable TV technicians because of the relative rarity of the skill, the number of years of education required to learn the skill, and the responsibilities involved in practising the skill.

Analyses of class inspired by Weber tend to emphasize gradations of status with regard to a number of variables like wealth, income, education, and occupation. Class stratification is not just determined by a group’s economic position but by the prestige of the group’s occupation, education level, consumption, and lifestyle. It is a matter of status — the level of honour or prestige one holds in the community by virtue of ones social position — as much as a matter of class. Based on the Weberian approach, some sociologists talk about upper, middle, and lower classes (with many subcategories within them) in a way that mixes status categories with class categories. These gradations are often referred to as a group’s socio-economic status (SES), their social position relative to others based on income, education, and occupation. For example, although plumbers might earn more than high school teachers and have greater life chances in a particular economy, the status division between blue-collar work (people who “work with their hands”) and white-collar work (people who “work with their minds”) means that plumbers, for example, are characterized as lower class but teachers as middle class. There is an arbitrariness to the division of classes into upper, middle, and lower.

However, this manner of classification based on status distinctions does capture something about the subjective experience of class and the shared lifestyle and consumption patterns of class that Marx’s categories often do not. An NHL hockey player receiving a salary of $6 million a year is a member of the working class, strictly speaking. He might even go on strike or get locked out according to the dynamic of capital/labour conflict described by Marx. Nevertheless it is difficult to see what the life chances of the hockey player have in common with a landscaper or truck driver, despite the fact they might share a common working-class background.

Social class is, therefore, a complex category to analyze. Social class has both a strictly material quality relating to a group’s structural position within the economic system, and a social quality relating to the formation of status gradations, common subjective perceptions of class, political divisions in society, and class-based lifestyles and consumption patterns. Taking into account both the Marxist and Weberian models, social class has at least three objective components: a group’s position in the occupational structure, a group’s position in the authority structure (i.e., who has authority over whom), and a group’s position in the property structure (i.e., ownership or non-ownership of capital). It also has an important subjective component that relates to recognitions of status, distinctions of lifestyle, and ultimately how people perceive their place in the class hierarchy.

One way of distinguishing the classes that takes this complexity into account is by focusing on the authority structure. Classes can be divided according to how much relative power and control members of a class have over their lives. On this basis, we might distinguish between the owning class (or bourgeoisie), the middle class, and the traditional working class. The owning class not only have power and control over their own lives, their economic position gives them power and control over others’ lives as well. To the degree that we can talk about a “middle class” composed of small business owners and educated, professional, or administrative labour, it is because they do not generally control other strata of society, but they do exert control over their own work to some degree. In contrast, the traditional working class has little control over their work or lives. But perhaps there is an even deeper subjective dimension to contemporary analyses of social class and its implications in society.

7.3.1. Class Traits and Markers

Class traits, also called class markers, are the typical behaviours, customs, and norms that define each class. They define a crucial subjective component of class identities. Class traits indicate the level of exposure a person has to a wide range of cultural resources. Class traits also indicate the amount of resources a person has to spend on items like hobbies, vacations, and leisure activities.

People may associate the upper class with enjoyment of costly, refined, or highly cultivated tastes — expensive clothing, luxury cars, high-end fundraisers, and opulent vacations. People may also believe that the middle and lower classes are more likely to enjoy camping, fishing, or hunting, shopping at large retailers, and participating in community activities. It is important to note that while these descriptions may be class traits, they may also simply be stereotypes. Moreover, just as class distinctions have blurred in recent decades, so too have class traits. A very wealthy person may enjoy bowling as much as opera. A factory worker could be a skilled French cook. Pop star Justin Bieber might dress in hoodies, ball caps, and ill fitting clothes, and a low-income hipster might own designer shoes.

These days, individual taste does not necessarily follow class lines. Still, you are not likely to see someone driving a Mercedes living in an inner-city neighbourhood. And most likely, a resident of a wealthy gated community will not be riding a bicycle to work. Class traits often develop based on cultural behaviours that stem from the resources available within each class.

7.3.2 Class Identity: Is it the Elephant in the Room?

Bourdieu’s concept of habitus was introduced at the beginning of this module. As previously defined, habitus refers to the deeply seated schemas, habits, feelings, dispositions, and forms of know-how that people hold due to their specific social backgrounds, cultures, and life experiences (1990). In short, our habitus is the way we embody and express our class identity in society, whether we are consciously aware of that embodiment and expression, or not. As this module draws to a close you are encouraged to use your understanding of interpretive sociology to reflect on how you, and people you know, embody class identity and how that embodiment impacts the opportunities and challenges that individuals experience in their everyday social realities.

Within interpretive sociology, symbolic interactionism is a theory that uses everyday interactions of individuals to explain society as a whole. Symbolic interactionism examines stratification from a micro-level perspective. This analysis strives to explain how people’s social standing affects their everyday interactions.

In most communities, people interact primarily with others who share the same social standing. It is precisely because of social stratification that people tend to live, work, and associate with others like themselves, people who share their same income level, educational background, or racial background, and even tastes in food, music, and clothing. The built-in system of social stratification groups people together.

Symbolic interactionists also note that people’s appearance reflects their perceived social standing. Housing, clothing, and transportation indicate social status, as do hairstyles, taste in accessories, and personal style. Pierre Bourdieu’s (1930-2002) concept of cultural capital suggests that cultural “assets” such as education and taste are accumulated and passed down between generations in the same manner as financial capital or wealth (1984). This marks individuals from an early age by such things as knowing how to wear a suit or having an educated manner of speaking. In fact the children of parents with a postsecondary degree are 60 percent likely to attend university themselves, while the children of parents with less than a high school education have only a 32 percent chance of attending university (Shaienks & Gluszynski, 2007).

Cultural capital is capital also in the sense of an investment, as it is expensive and difficult to attain while providing access to better occupations. Bourdieu argued that the privilege accorded to those who hold cultural capital is a means of reproducing the power of the ruling classes. People with the “wrong” cultural attributes have difficulty attaining the same privileged status. Cultural capital becomes a key measure of distinction between social strata.

In the Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), Thorstein Veblen (1857-1929) described the activity of conspicuous consumption as the tendency of people to buy things as a display of status rather than out of need. Conspicuous consumption refers to buying certain products to make a social statement about status. Carrying pricey but eco-friendly water bottles could indicate a person’s social standing. Some people buy expensive trendy sneakers even though they will never wear them to jog or play sports. A $17,000 car provides transportation as easily as a $100,000 vehicle, but the luxury car makes a social statement that the less-expensive car can’t live up to. All of these symbols of stratification are worthy of examination by interpretive sociologists because their social significance is determined by the shared meanings they hold.

Key Terms

achieved status: A status received through individual effort or merits (eg. occupation, educational level, moral character, etc.).

ascribed status: A status received by virtue of being born into a category or group (eg. hereditary position, gender, race, etc.).

bourgeoisie: In capitalism, the owning class who live from the proceeds of owning or controlling productive property (capital assets like factories and machinery, or capital itself in the form of investments, stocks, and bonds).

class: A group who shares a common social status based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation.

class system: Social standing based on social factors and individual accomplishments.

class traits: The typical behaviours, customs, and norms that define each class, also called class markers.

conspicuous consumption: Buying and using products to make a statement about social standing.

cultural capital: Cultural assets in the form of knowledge, education, and taste that can be transferred intergenerationally.

downward mobility: A lowering of one’s social class.

equality of condition: A situation in which everyone in a society has a similar level of wealth, status, and power.

equality of opportunity: A situation in which everyone in a society has an equal chance to pursue economic or social rewards.

income: The money a person earns from work or investments.

intergenerational mobility: A difference in social class between different generations of a family.

intragenerational mobility: A difference in social class between different members of the same generation.

living wage: The income needed to meet a family’s basic needs and enable them to participate in community life.

lumpenproletariat: In capitalism, the underclass of chronically unemployed or irregularly employed who are in and out of the workforce.

means of production: Productive property, including the things used to produce the goods and services needed for survival: tools, technologies, resources, land, workplaces, etc.

meritocracy: An ideal system in which personal effort—or merit—determines social standing.

petite bourgeoisie: In capitalism, the class of small owners like shopkeepers, farmers, and contractors who own some property and perhaps employ a few workers but rely on their own labour to survive.

power: How many people a person must take orders from versus how many people a person can give orders to.

proletariat: Those who seek to establish a sustainable standard of living by maintaining the level of their wages and the level of employment in society.

proletarianization (the act of being proletarianized): The process in which the work conditions of the middle class increasingly resemble those of the traditional, blue-collar working class.

social differentiation: The division of people into categories based on socially significant characteristics, identities, and roles.

social inequality: The unequal distribution of valued resources, rewards, and positions in a society.

social mobility: The ability to change positions within a social stratification system.

social stratification: A socioeconomic system that divides society’s members into categories ranking from high to low, based on things like wealth, power, and prestige.

socio-economic status (SES): A group’s social position in a hierarchy based on income, education, and occupation.

standard of living: The level of wealth available to acquire material goods and comforts to maintain a particular socioeconomic lifestyle.

status: The degree of honour or prestige one has in the eyes of others.

status consistency: The consistency, or lack thereof, of an individual’s rank across social categories like income, education, and occupation.

structural mobility: When societal changes enable a whole group of people to move up or down the class ladder.

upward mobility: An increase — or upward shift — in social class.

wealth: The value of money and assets a person has from, for example, inheritance.

7.4 References

Abercrombie, N., & Urry, J. (1983). Capital, labour and the middle classes. London, UK: George Allen & Unwin.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Pierre Bourdieu 1984

Boyd, M. (2008). A socioeconomic scale for Canada: measuring occupational status from the census. Canadian Review of Sociology, 45(1), 51-91.

CBC RadioCBC Radio. (2010, September 14). Part 3: Former gang members. The Current [Audio file]. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/thecurrent/2010/09/september-14-2010.html.

The Division of Labour in Society (1893/1960), Durkheim

Marx (1848/1977)

Marx (1932/1977)

Office of the Correctional Investigator, 2013

Rogers, T., & Brehl, R. (2008). Ted Rogers: Relentless. The true story of the man behind Rogers Communications. Toronto, ON: HarperCollins.

Shaienks & Gluszynski, 2007

Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), Thorstein Veblen (1857-1929)

Weber, M. (1969). Class, status and party. In Gerth & Mills (Eds.), Max Weber: Essays in sociology (pp. 180-195). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.