4 Module 4: Research Design: Collecting and Interpreting The Data of Everyday Social Reality

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between between quantitative and qualitative research in terms of focus, philosophical roots, goals, design and data collection methods

- List and briefly describe the three primary goals of qualitative research

- List and briefly describe typical sources of qualitative data (e.g., Interviews, focus groups, observations and documents)

- List and briefly describe the primary methods of qualitative data analysis (i.e., preparing, summarizing and presenting qualitative data)

- List the primary strategies for determining the validity of qualitative data

- Explain when qualitative research methods are appropriate for a research study

- Explain why it is important to communicate research findings to both, specialized academic audiences and general public audiences

4.1 Introduction to Qualitative Inquiry and Methods of Data Collection and Analysis

Sociologists examine the social world, see a problem or interesting pattern in that world, and set out to study it. They use research methods to design a study — perhaps a positivist, quantitative method for conducting research and obtaining data to explain, predict or control an aspect of social reality; or alternatively, an ethnographic study utilizing an interpretive framework to produce enhanced understanding of the meaning and process of social action and interaction within complex social environments. Planning the research design is a key step in any sociological study. As described in Module Three, there are multiple layers of research design that need to be taken into consideration. Using the research onion metaphor developed by Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill (2012), the outer layers of the onion (research philosophies, modes of reasoning, and time horizons) point to the various conceptual and logical decisions that inform the process of research inquiry undertaken within particular studies. In discussing the outer layers of the research onion in Module Three, emphasis was placed on a selection of research philosophies and modes of reasoning that inform the collection and interpretation of empirical evidence in the form of meanings, experiences and motivations. Those meanings, experiences and motivations that inform the social actions and social interactions of human actors within the contexts of their everyday social realities. Module Four begins with a brief overview of the conceptual dimensions of qualitative research inquiry before shifting to an examination of the more concrete strategies and methods involved in collecting, summarizing, interpreting and representing various types of qualitative data.

(Overview of Qualitative Research Methods available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IsAUNs-IoSQ )

Researchers who work with qualitative research methods seek to understand social worlds from the perspectives of the participants. Following the lead of Weber’s Verstehende sociology (See Module Two) and drawing on the theoretical insights of various classical thinkers (e.g., Simmel, Cooley, Mead, Goffman, DuBois), contemporary social constructionists (e.g., Smith, Hochschild) and/or critical thinkers (e.g., Habermas, Foucault, Bourdieu) qualitative researchers generally choose from four widely used data collection strategies. These strategies include field research, secondary data analysis, case study and participatory action research (PAR). Every data collection method comes with pluses and minuses, and the topic of study and research question are primary factors in deciding which method or methods are put to use. The various features, strengths and weaknesses of each of these strategies is discussed below.

4.2 Methods of Data Collection for Qualitative Inquiry

4.2.1 Field Research

The work of sociological data collection rarely happens in limited, confined spaces. Sociologists seldom study subjects in their own offices or laboratories. Rather, sociologists go out into the world. They meet subjects where they live, work, and play. Field research refers to gathering primary data from a natural environment without doing a lab experiment or a survey. It is a research method suited to an interpretive approach rather than to positivist approaches. To conduct field research, the sociologist must be willing to step into new environments and observe, participate, or experience those worlds. In fieldwork, the sociologists, rather than the subjects, are the ones out of their element. The researcher interacts with or observes a person or people, gathering data along the way. The key point in field research is that it takes place in the subject’s natural environment, whether it’s a coffee shop or tribal village, a homeless shelter or a care home, a hospital, airport, mall, or beach resort.

While field research often begins in a specific setting, the study’s purpose is to observe specific behaviours in that setting. Fieldwork is optimal for observing how people behave. It is less useful, however, for developing causal explanations of why they behave that way. From the small size of the groups studied in fieldwork, it is difficult to make predictions or generalizations to a larger population. Similarly, there are difficulties in gaining an objective distance from research subjects. It is difficult to know whether another researcher would see the same things or record the same data. We will look at three types of field research: participant observation, ethnography, and institutional ethnography.

Participant Observation

Participant observation, is a form of study in which researchers join people and participate in a group’s routine activities for the purpose of observing them within that context. This method lets researchers study a naturally occurring social activity without imposing artificial or intrusive research devices, like fixed questionnaire questions, onto the situation. A researcher might go to great lengths to get a firsthand look into a trend, institution, or behaviour. Researchers temporarily put themselves into “native” roles and record their observations. A researcher might work as a waitress in a diner, or live as a homeless person for several weeks, or ride along with police officers as they patrol their regular beat. Often, these researchers try to blend in seamlessly with the population they study, and they may not disclose their true identity or purpose if they feel it would compromise the results of their research. The issue of disclosure is also an ethical one and as such, deciding not to disclose one’s identity as a researcher would need to be justified and approved by an ethics review board before being used as a strategy within any particular research study.

At the beginning of a field study, researchers might have a question: “What really goes on in the kitchen of the most popular diner on campus?” or “What is it like to be homeless?” Participant observation is a useful method if the researcher wants to explore a certain environment from the inside. Field researchers simply want to observe and learn. In such a setting, the researcher will be alert and open minded to whatever happens, recording all observations accurately. Soon, as patterns emerge, questions will become more specific, observations will lead to hypotheses, and hypotheses will guide the researcher in shaping data into results.

In a study of small town America conducted by sociological researchers John S. Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd, the team altered their purpose as they gathered data. They initially planned to focus their study on the role of religion in American towns. As they gathered observations, they realized that the effect of industrialization and urbanization was the more relevant topic of this social group. The Lynds did not change their methods, but they revised their purpose. This shaped the structure of Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture, their published results (Lynd & Lynd, 1959).

The Lynds were upfront about their mission. The townspeople of Muncie, Indiana knew why the researchers were in their midst. But some sociologists prefer not to alert people to their presence. The main advantage of covert participant observation is that it allows the researcher access to authentic, natural behaviours of a group’s members. The challenge, however, is gaining access to a setting without disrupting the pattern of others’ behaviour. Becoming an inside member of a group, organization, or subculture takes time and effort. Researchers must pretend to be something they are not. The process could involve role playing, making contacts, networking, or applying for a job. Once inside a group, some researchers spend months or even years pretending to be one of the people they are observing. However, as observers, they cannot get too involved. They must keep their purpose in mind and apply the sociological perspective. That way, they illuminate social patterns that are often unrecognized. Because information gathered during participant observation is mostly qualitative, rather than quantitative, the end results are often descriptive or interpretive. The researcher might present findings in an article or book, describing what he or she witnessed and experienced.

This type of research is what journalist Barbara Ehrenreich conducted for her book Nickel and Dimed. One day over lunch with her editor, as the story goes, Ehrenreich mentioned an idea. “How can people exist on minimum-wage work? How do low-income workers get by?” she wondered. “Someone should do a study.” To her surprise, her editor responded, “Why don’t you do it?” That is how Ehrenreich found herself joining the ranks of the low-wage service sector. For several months, she left her comfortable home and lived and worked among people who lacked, for the most part, higher education and marketable job skills. Undercover, she applied for and worked minimum wage jobs as a waitress, a cleaning woman, a nursing home aide, and a retail chain employee. During her participant observation, she used only her income from those jobs to pay for food, clothing, transportation, and shelter. She discovered the obvious: that it’s almost impossible to get by on minimum wage work. She also experienced and observed attitudes many middle- and upper-class people never think about. She witnessed firsthand the treatment of service work employees. She saw the extreme measures people take to make ends meet and to survive. She described fellow employees who held two or three jobs, worked seven days a week, lived in cars, could not pay to treat chronic health conditions, got randomly fired, submitted to drug tests, and moved in and out of homeless shelters. She brought aspects of that life to light, describing difficult working conditions and the poor treatment that low-wage workers suffer.

Blending into the social context that one wishes to study is not always a realistic option for the researcher and in those situations it is important to be mindful of the Hawthorne Effect. In the 1920s, leaders of a Chicago factory called Hawthorne Works commissioned a study to determine whether or not changing certain aspects of working conditions could increase or decrease worker productivity. Sociologists were surprised when the productivity of a test group increased when the lighting of their workspace was improved. They were even more surprised when productivity improved when the lighting of the workspace was dimmed. In fact almost every change of independent variable — lighting, breaks, work hours — resulted in an improvement of productivity. But when the study was over, productivity dropped again.

Why did this happen? In 1953, Henry A. Landsberger analyzed the study results to answer this question. He realized that employees’ productivity increased because sociologists were paying attention to them. The sociologists’ presence influenced the study results. Worker behaviours were altered not by the lighting but by the study itself. From this, sociologists learned the importance of carefully planning their roles as part of their research design (Franke & Kaul, 1978). Landsberger called the workers’ response the Hawthorne effect — people changing their behaviour because they know they are being watched as part of a study.

The Hawthorne effect is unavoidable in some research. In many cases, sociologists have to make the purpose of the study known for ethical reasons. Subjects must be aware that they are being observed, and a certain amount of artificiality may result (Sonnenfeld, 1985). Making sociologists’ presence invisible is not always realistic for other reasons. That option is not available to a researcher studying prison behaviours, early education, or the Ku Klux Klan. Researchers cannot just stroll into prisons, kindergarten classrooms, or Ku Klux Klan meetings and unobtrusively observe behaviours. In situations like these, other methods are needed. All studies shape the research design, while research design simultaneously shapes the study. Researchers choose methods that best suit their study topic and that fit with their overall goal for the research.

Choosing a research methodology depends on a number of factors, including the purpose of the research and the audience for whom the research is intended. If we consider the type of research that might go into producing a government policy document on the effectiveness of safe injection sites for reducing the public health risks of intravenous drug use, we would expect public administrators to want “hard” (i.e., quantitative) evidence of high reliability to help them make a policy decision. The most reliable data would come from an experimental or quasi-experimental research model in which a control group can be compared with an experimental group using quantitative measures.

This approach has been used by researchers studying InSite in Vancouver (Marshall et al., 2011; Wood et al., 2006). InSite is a supervised safe-injection site where heroin addicts and other intravenous drug users can go to inject drugs in a safe, clean environment. Clean needles are provided and health care professionals are on hand to intervene in the case of overdoses or other medical emergency. It is a controversial program both because heroin use is against the law (the facility operates through a federal ministerial exemption) and because the heroin users are not obliged to quit using or seek therapy. To assess the effectiveness of the program, researchers compared the risky usage of drugs in populations before and after the opening of the facility and geographically near and distant to the facility. The results from the studies have shown that InSite has reduced both deaths from overdose and risky behaviours, such as the sharing of needles, without increasing the levels of crime associated with drug use and addiction.

On the other hand, if the research question is more exploratory (for example, trying to discern the reasons why individuals in the crack smoking subculture engage in the risky activity of sharing pipes), the more nuanced approach of fieldwork is more appropriate. The research would need to focus on the subcultural context, rituals, and meaning of sharing pipes, and why these phenomena override known health concerns. Graduate student Andrew Ivsins at the University of Victoria studied the practice of sharing pipes among 13 habitual users of crack cocaine in Victoria, B.C. (Ivsins, 2010). He met crack smokers in their typical setting downtown and used an unstructured interview method to try to draw out the informal norms that lead to sharing pipes. One factor he discovered was the bond that formed between friends or intimate partners when they shared a pipe. He also discovered that there was an elaborate subcultural etiquette of pipe use that revolved around the benefit of getting the crack resin smokers left behind. Both of these motives tended to outweigh the recognized health risks of sharing pipes (such as hepatitis) in the decision making of the users. This type of research was valuable in illuminating the unknown subcultural norms of crack use that could still come into play in a harm reduction strategy such as distributing safe crack kits to addicts.

Ethnography

Ethnography is the extended observation of the social perspective and cultural values of an entire social setting. Researchers seek to immerse themselves in the life of a bounded group by living and working among them. Often ethnography involves participant observation, but the focus is the systematic observation of an entire community. The heart of an ethnographic study focuses on how subjects view their own social standing and how they understand themselves in relation to a community. It aims at developing a “thick description” of people’s behaviour that describes not only the behaviour itself but the layers of meaning that form the context of the behaviour (Geertz, 1973). An ethnographic study might observe, for example, a small Newfoundland fishing town, an Inuit community, a scientific research laboratory, a backpacker’s hostel, a private boarding school, or Disney World. These places all have borders. People live, work, study, or vacation within those borders. People are there for a certain reason and therefore behave in certain ways and respect certain cultural norms. An ethnographer would commit to spending a determined amount of time studying every aspect of the chosen place, taking in as much as possible, and keeping careful notes on his or her observations. A sociologist studying ayahuasca ceremonies in the Amazon might learn the language, watch the way shamans go about their daily lives, ask individuals about the meaning of different aspects of the activity, study the group’s cosmology, and then write a paper about it. To observe a Buddhist retreat centre, an ethnographer might sign up for a retreat and attend as a guest for an extended stay, observe and record how people experience spirituality in this setting, and collate the material into results.

Institutional Ethnography

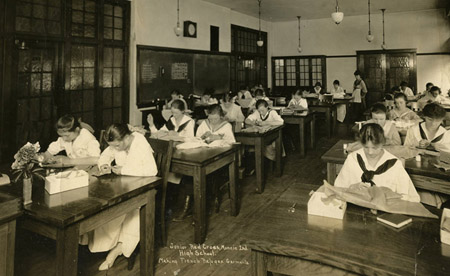

Dorothy Smith elaborated on traditional ethnography to develop what she calls institutional ethnography (2005). In modern society the practices of everyday life in any particular local setting are often organized at a level that goes beyond what an ethnographer might observe directly. Everyday life is structured by “extralocal,” institutional forms; that is, by the practices of institutions that act upon people from a distance. It might be possible to conduct ethnographic research on the experience of domestic abuse by living in a women’s shelter and directly observing and interviewing victims to see how they form an understanding of their situation. However, to the degree that the women are seeking redress through the criminal justice system a crucial element of the situation would be missing. In order to activate a response from the police or the courts, a set of standard legal procedures must be followed, a case file must be opened, legally actionable evidence must be established, forms filled out, etc. All of this allows criminal justice agencies to organize and coordinate the response.The urgent and immediate experience of the domestic abuse victims needs to be translated into a format that enables distant authorities to take action. Often this is a frustrating and mysterious process in which the immediate needs of individuals are neglected so that needs of institutional processes are met. Therefore, to research the situation of domestic abuse victims, an ethnography needs to somehow operate at two levels: the close examination of the local experience of particular women and the simultaneous examination of the extralocal, institutional world through which their world is organized. In order to accomplish this, institutional ethnography focuses on the study of the way everyday life is coordinated through “textually mediated” practices: the use of written documents, standardized bureaucratic categories, and formalized relationships (Smith, 1990). Institutional paperwork translates the specific details of locally lived experience into a standardized format that enables institutions to apply the institution’s understandings, regulations, and operations in different local contexts. A study of these textual practices reveals otherwise inaccessible processes that formal organizations depend on: their formality, their organized character, their ongoing methods of coordination, etc. An institutional ethnography often begins by following the paper trail that emerges when people interact with institutions: How does a person formulate a narrative about what has happened to him or her in a way that the institution will recognize? How is it translated into the abstract categories on a form or screen that enable an institutional response to be initiated? What is preserved in the translation to paperwork, and what is lost? Where do the forms go next? What series of “processing interchanges” take place between different departments or agencies through the circulation of paperwork? How is the paperwork modified and made actionable through this process (e.g., an incident report, warrant request, motion for continuance)?Smith’s insight is that the shift from the locally lived experience of individuals to the extralocal world of institutions is nothing short of a radical metaphysical shift in worldview. In institutional worlds, meanings are detached from directly lived processes and reconstituted in an organizational time, space, and consciousness that is fundamentally different from their original reference point. For example, the crisis that has led to a loss of employment becomes a set of anonymous criteria that determines one’s eligibility for Employment Insurance.The unique life of a disabled child becomes a checklist that determines the content of an “individual education program” in the school system, which in turn determines whether funding will be provided for special aid assistants or therapeutic programs. Institutions put together a picture of what has occurred that is not at all the same as what was lived. The ubiquitous but obscure mechanism by which this is accomplished is textually mediated communication. The goal of institutional ethnography, therefore, is to make “documents or texts visible as constituents of social relations” (Smith, 1990). Institutional ethnography is very useful as a critical research strategy. It is an analysis that gives grassroots organizations, or those excluded from the circles of institutional power, a detailed knowledge of how the administrative apparatuses actually work. This type of research enables more effective actions and strategies for change to be pursued.

4.2.2 Secondary Data, Archival Data and Methods of Textual Analysis

While sociologists often engage in original research studies, they also contribute knowledge to the discipline through secondary data. Within qualitative inquiry, secondary data is frequently in the form of archival materials which may be formally stored in an archive or exist in the files and records of public and private organizations as well as private persons. Secondary data do not result from firsthand research collected from primary sources, but are drawn from the already-completed work of other researchers, scholars and writers (e.g., the texts of historians, economists, anthropologists, sociologists, teachers, journalists), records produced as a result of the everyday activities within various organizational contexts (e.g., government offices, non-profit organizations, private businesses and corporations), and personal memoirs (e.g., correspondence, diaries, photographs). In the contemporary context of digital technologies and communications, the internet is a rich and expanding resource of various types of text (e.g., written and image based) for the purpose of sociological analysis (e.g., website pages, facebook, twitter, blogs, etc.) alongside more traditional sources such as periodicals, newspapers, or magazines from any period in history. Using available information not only saves time and money, but it can add depth to a study. Sociologists often interpret findings in a new way, a way that was not part of an author’s original purpose or intention. To study how women were encouraged to act and behave in the 1960s, for example, a researcher might watch movies, televisions shows, and situation comedies from that period. Or to research changes in behaviour and attitudes due to the emergence of television in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a sociologist would rely on new interpretations of secondary data. Decades from now, researchers will most likely conduct similar studies on the advent of mobile phones, the internet, or Facebook. Within sociological inquiry the potential sources of secondary data are limited only by the imagination of individual researchers. A particularly rich and longitudinal source of data for the study of everyday social reality is provided in the Mass Observation Project located in the UK.

Video

Watch the video “Mass Observation Project” at http://sk.sagepub.com/video/sociology-of-everyday-life-inpr?fromsearch=true (USASK students should be able to see this video by clicking the link. If the link does not work, access the video Module 4 in the Learning Management System course site.

One methodology that sociologists employ with secondary data is content analysis. Content analysis is a quantitative approach to textual research that selects an item of textual content (i.e., a variable) that can be reliably and consistently observed and coded, and surveys the prevalence of that item in a sample of textual output. For example, Gilens (1996) wanted to find out why survey research shows that the American public substantially exaggerates the percentage of African Americans among the poor. He examined whether media representations influence public perceptions and did a content analysis of photographs of poor people in American news magazines. He coded and then systematically recorded incidences of three variables: (1) race: white, black, indeterminate; (2) employed: working, not working; and (3) age. Gilens discovered that not only were African Americans markedly overrepresented in news magazine photographs of poverty, but that the photos also tended to under represent “sympathetic” subgroups of the poor—the elderly and working poor—while over representing less sympathetic groups—unemployed, working age adults. Gilens concluded that by providing a distorted representation of poverty, U.S. news magazines “reinforce negative stereotypes of blacks as mired in poverty and contribute to the belief that poverty is primarily a ‘black problem’” (1996).

Textual analysis is a qualitative methodology use to examine the structure, style, content, purpose and symbolic meaning of various written, oral and visual texts. The roots of textual analysis extend into the humanities and draw on the theory and methodologies of hermeneutic interpretation and linguistics (the science of language). Within the broader domain of textual analysis, narrative analysis draws on the strategies and techniques of literary scholars to analyze the stories people create and use to express meaning and experience within the context of everyday lived reality. Discourse analysis, another form of textual analysis, finds its roots in linguistics and is an interpretive approach to texts that focuses on the contextual meanings and social uses of larger chunks of communication. In addition to there being multiple sources of secondary data for the purpose of sociological analysis, there are a variety of analytical tools and techniques that can be drawn on from the domains of science and the humanities to enhance our capacity as sociologists to understand meaning and motivation within the context of everyday social reality.

(Linguistics and Discourse Analysis in available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JZ8bkus3vis)

Social scientists also learn by analyzing the research of a variety of agencies. Governmental departments, public interest research groups, and global organizations like Statistics Canada, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, or the World Health Organization publish studies with findings that are useful to sociologists. A public statistic that measures inequality of incomes might be useful for studying who benefited and who lost as a result of the 2008 recession; a demographic profile of different immigrant groups might be compared with data on unemployment to examine the reasons why immigration settlement programs are more effective for some communities than for others. One of the advantages of secondary data is that it is nonreactive (or unobtrusive) research, meaning that it does not include direct contact with subjects and will not alter or influence people’s behaviours. Unlike studies requiring direct contact with people, using previously published data does not require entering a population and the investment and risks inherent in that research process.

Using available data does have its challenges. Public records are not always easy to access. A researcher needs to do some legwork to track them down and gain access to records. In some cases there is no way to verify the accuracy of existing data. It is easy, for example, to count how many drunk drivers are pulled over by the police. But how many are not? While it’s possible to discover the percentage of teenage students who drop out of high school, it might be more challenging to determine the number who return to school or get their high school diplomas later. Another problem arises when data are unavailable in the exact form needed or do not include the precise angle the researcher seeks. For example, the salaries paid to professors at universities are often published, but the separate figures do not necessarily reveal how long it took each professor to reach the salary range, what their educational backgrounds are, or how long they have been teaching.

In his research, sociologist Richard Sennett uses secondary data to shed light on current trends. In The Craftsman (2008), he studied the human desire to perform quality work, from carpentry to computer programming. He studied the line between craftsmanship and skilled manual labour. He also studied changes in attitudes toward craftsmanship that occurred not only during and after the Industrial Revolution, but also in ancient times. Obviously, he could not have firsthand knowledge of periods of ancient history, so he had to rely on secondary data for part of his study.

When conducting secondary data or textual analysis, it is important to consider the date of publication of an existing source and to take into account attitudes and common cultural ideals that may have influenced the research. For example, Robert and Helen Lynd gathered research for their book Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture in the 1920s. Attitudes and cultural norms were vastly different then than they are now. Beliefs about gender roles, race, education, and work have changed significantly since then. At the time, the study’s purpose was to reveal the truth about small American communities. Today, it is an illustration of 1920s attitudes and values. An important principle for sociological researchers to be mindful of is to exercise caution when presuming to impose today’s values and attitudes on the practices and circumstances of the past.

4.2.3 Case Studies

A case study is an in-depth analysis of a single event, social situation, individual, organization, community, or process. To conduct a case study, a researcher typically collects or accesses data from a variety of sources. Data collection strategies may include the examination of existing documents and archival records, interviews with key informants, direct observation, and even participant observation, if possible. While there is no single definition of the case study method, the approach generally involves an intense investigation of a bounded (i.e., spatial or temporal) phenomena within its natural context. For example, researchers might use this method to study a single case of a foster child, drug lord, cancer patient, criminal, or sexual assault victim or they could develop a multiple case study design to facilitate comparative analysis. Alternatively, the case study researcher may examine an exemplary event within the context of an entire community or organization. The primary purposes of case study research are illustrative, descriptive, explanatory and exploratory. A major criticism of the case study as a method is that a developed study of a single case, while offering depth on a topic, does not provide enough evidence to form a generalized conclusion. In other words, it is difficult to make universal claims based on just one case, since one case does not verify a pattern.

However, case studies are useful when the single case is unique. In these instances, a single case study can add tremendous knowledge to a certain discipline. For example, a feral child, also called “wild child,” is one who grows up isolated from human beings. Feral children grow up without social contact and language, which are elements crucial to a “civilized” child’s development. These children mimic the behaviours and movements of animals, and often invent their own language. There are only about 100 cases of feral children in the world. As you may imagine, a feral child is a subject of great interest to researchers. Feral children provide unique information about child development because they have grown up outside of the parameters of normal child development. And since there are very few feral children, the case study is the most appropriate method for researchers to use in studying the subject. At age three, a Ukrainian girl named Oxana Malaya suffered severe parental neglect. She lived in a shed with dogs, eating raw meat and scraps. Five years later, a neighbour called authorities and reported seeing a girl who ran on all fours, barking. Officials brought Oxana into society, where she was cared for and taught some human behaviours, but she never became fully socialized. She has been designated as unable to support herself and now lives in a mental institution (Grice, 2006). Case studies like this offer a way for sociologists to collect data that may not be collectable by any other method.

4.2.4 Community Based Participatory Action Research

Community Based Participatory Action Research (CBPAR) is a methodological approach to research that not only seeks to understand the social world, or a part of the social world, but also to change it in a particular, normative direction. Photovoice or photoelicitation is a form of qualitative, textual inquiry that uses visual imagery and dialogue between researchers and participants to democratize the researcher participant relationship and enable participants to represent and express experiences and meanings in ways that are meaningful to the standpoints and perspectives of the research participants.

(Photovoice is available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ok5TQ-P77U)

4.3 Reporting and Translating Qualitative Research Findings

Sociological researchers are motivated, and ethically obliged, to communicate the process and findings of their research to other social scientists. The rationale for this is twofold. On the one hand, research findings serve to advance and improve the knowledge base of the discipline. On the other, researchers are obliged to subject their logics, methods and findings to other members of the scholarly community for scrutiny and evaluation (See CUDOS, Module 3). The primary avenue for achieving this objective is via peer reviewed academic journals which are considered the gold standard of the scientific and scholarly community. In addition to publishing research articles in peer reviewed academic journals and other media primarily oriented to other social scientists, the knowledge outcomes of sociological research are also communicated in forms accessible to research participants, policy makers and members of the public more generally. In the case of qualitative inquiry, where researchers are confronted with a need to communicate meaning and emotion alongside social and historical facts, the knowledge, techniques and strategies of the fine and popular arts provide a rich resource.

(With Glowing Hearts: Academic Page to Popular Stage is available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h5yYY-UEGyQ)

Key Terms and Concepts

Archival data: A type of secondary data that consists of documentary material left by people and organizations as a product of their everyday lives.

Case study: In-depth analysis of a single event, situation, or individual.

Content Analysis: A quantitative approach to textual research that selects an item of textual content that can be reliably and consistently observed and coded, and surveys the prevalence of that item in a sample of textual output.

Ethnography: Observing a complete social setting and all that it entails.

Field research: Gathering data from a natural environment without doing a lab experiment or a survey.

Hawthorne effect: When study subjects behave in a certain manner due to their awareness of being observed by a researcher.

Hermeneutic: A theory and methodology of interpretation.

Institutional ethnography: The study of the way everyday life is coordinated through institutional, textually mediated practices.

Nonreactive: Unobtrusive research that does not include direct contact with subjects and will not alter or influence people’s behaviours.

Participant observation: Immersion by a researcher in a group or social setting in order to make observations from an “insider” perspective.

Primary data: Data collected directly from firsthand experience.

Research design: the set of methods and procedures used in collecting and analyzing measures of the variables specified in the problem research. (Creswell, J. 2017).

Secondary data analysis: Using data collected by others but applying new interpretations.

Textual analysis: Using data collected by others but applying new interpretations.

Textually mediated communication: Institutional forms of communication that rely on written documents, texts, and paperwork.

References

Cotter, A. (2014). Firearms and violent crime in Canada, 2012. Juristat (Statistics Canada catalogue No. 85-002-X). Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2014001/article/11925-eng.htm.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Franke, R., & Kaul, J. (1978). The Hawthorne experiments: First statistical interpretation. American Sociological Review, 43(5), 632–643.

Geertz, C. (1977). Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. In The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays (pp. 3-30). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gilens, M. (1996). Race and poverty in America: Public misperceptions and the American news media. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 60(4), 515–541.

Grice, E. (2006). Cry of an enfant sauvage. The Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/3653890/Cry-of-an-enfant-sauvage.html.

Ivsins, A. K. (2010). “Got a pipe?” The social dimensions and functions of crack pipe sharing among crack users in Victoria, BC [PDF] (Master’s thesis, Department of Sociology, University of Victoria). Retrieved from http://dspace.library.uvic.ca:8080/bitstream/handle/1828/3044/Full%20thesis%20Ivsins_CPS.2010_FINAL.pdf?sequence=1.

Lynd, R. S., & Lynd, H. M. (1959). Middletown: A study in modern American culture. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Javanovich.

Marshall, B. D. L., Milloy, M. J., Wood, E., Montaner, J. S. G., & Kerr, T. (2011). Reduction in overdose mortality after the opening of North America’s first medically supervised safer injecting facility: A retrospective population-based study. Lancet, 377(9775), 1429–1437.

Saunders, M., P. Lewis, and A. Thornhill. “Research Methods for Business Students . Gosport.” (2003).

Sennett, R. (2008). The craftsman. Retrieved from http://www.richardsennett.com/site/SENN/Templates/General.aspx?pageid=40.

Smith, D. (1990). Textually mediated social organization. In Texts, facts and femininity: Exploring the relations of ruling (pp. 209–234). London: Routledge.

Smith, D. (2005). Institutional ethnography: A sociology for people. Toronto, ON: Altamira Press.

Sonnenfeld, J. A. (1985). Shedding light on the Hawthorne studies. Journal of Occupational Behavior 6, 125.

Wood, E., Tyndall, M. W., Montaner, J. S., & Kerr, T. (2006). Summary of findings from the evaluation of a pilot medically supervised safer injecting facility. Canadian Medical Association Journal 175(11), 1399–1404.