12 Module 12: Collective Resistance and Social Change

Learning Objectives

- Describe different forms of collective behaviour.

- Differentiate between types of crowds.

- Discuss emergent norm, value-added, and assembling perspective analyses of collective behaviour.

- Describe social movements on a state, national, and global level.

- Distinguish between different types of social movements.

- Identify stages of social movements.

- Discuss theoretical perspectives on social movements, like resource mobilization, framing, and new social movement theory.

- Explain how technology, social institutions, population, and the environment can bring about social change.

- Discuss the importance of modernization in relation to social change.

12.0 Introduction to Social Movements and Social Change

In January 2011, Egypt erupted in protests against the stifling rule of longtime President Hosni Mubarak. The protests were sparked in part by the revolution in Tunisia, and, in turn, they inspired demonstrations throughout the Middle East in Libya, Syria, and beyond. This wave of protest movements travelled across national borders and seemed to spread like wildfire. There have been countless causes and factors in play in these protests and revolutions, but many have noted the internet-savvy youth of these countries. Some believe that the adoption of social technology — from Facebook pages to cell phone cameras — that helped to organize and document the movement contributed directly to the wave of protests called Arab Spring. The combination of deep unrest and disruptive technologies meant these social movements were ready to rise up and seek change.

What do Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), the anti-globalization movement, and the Tea Party have in common? Not much, you might think. But although they may be left-wing or right-wing, radical or conservative, highly organized or very diffused, they are all examples of social movements.

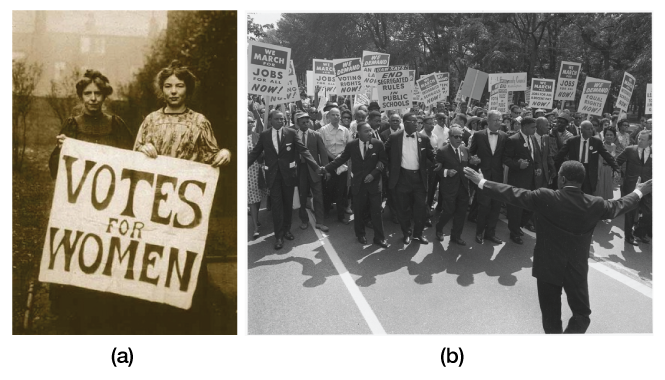

Social movements are purposeful, organized groups striving to work toward a common goal. These groups might be attempting to create change (Occupy Wall Street, Arab Spring), to resist change (anti-globalization movement), or to provide a political voice to those otherwise disenfranchised (civil rights movements). Social movements create social change.

Consider the effect of the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. This disaster exemplifies how a change in the environment, coupled with the use of technology to fix that change, combined with anti-oil sentiment in social movements and social institutions, led to changes in offshore oil drilling policies. Subsequently, in an effort to support the Gulf Coast’s rebuilding efforts, changes occurred. From grassroots marketing campaigns that promote consumption of local seafood to municipal governments needing to coordinate with federal cleanups, organizations develop and shift to meet the changing needs of the society. Just as we saw with the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, social movements have, throughout history, influenced societal shifts. Sociology looks at these movments through the lenses of three major perspectives.

The functionalist perspective looks at the big picture, focusing on the way that all aspects of society are integral to the continued health and viability of the whole. A functionalist might focus on why social movements develop, why they continue to exist, and what social purposes they serve. On one hand, social movements emerge when there is a dysfunction in the relationship between systems. The union movement developed in the 19th century when the economy no longer functioned to distribute wealth and resources in a manner that provided adequate sustenance for workers and their families. On the other hand, when studying social movements themselves, functionalists observe that movements must change their goals as initial aims are met or they risk dissolution. Several organizations associated with the anti-polio industry folded after the creation of an effective vaccine that made the disease virtually disappear. Can you think of another social movement whose goals were met? What about one whose goals have changed over time?

The critical perspective focuses on the creation and reproduction of inequality. Someone applying the conflict perspective would likely be interested in how social movements are generated through systematic inequality, and how social change is constant, speedy, and unavoidable. In fact, the conflict that this perspective sees as inherent in social relations drives social change. For example, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was founded in the United States in 1908. Partly created in response to the horrific lynchings occurring in the southern United States, the organization fought to secure the constitutional rights guaranteed in the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, which established an end to slavery, equal protection under the law, and universal male suffrage (NAACP, 2011). While those goals have been achieved, the organization remains active today, continuing to fight against inequalities in civil rights and to remedy discriminatory practices.

The symbolic interaction perspective studies the day-to-day interaction of social movements, the meanings individuals attach to involvement in such movements, and the individual experience of social change. An interactionist studying social movements might address social movement norms and tactics as well as individual motivations. For example, social movements might be generated through a feeling of deprivation or discontent, but people might actually join social movements for a variety of reasons that have nothing to do with the cause. They might want to feel important, or they know someone in the movement they want to support, or they just want to be a part of something. Have you ever been motivated to show up for a rally or sign a petition because your friends invited you? Would you have been as likely to get involved otherwise?

12.1 Collective Behaviour

12.1.1 Flash Mobs

People sitting in a café in a touristy corner of Rome might expect the usual sights and sounds of a busy city. They might be more surprised when, as they sip their espressos, hundreds of young people start streaming into the picturesque square clutching pillows, and when someone gives a signal, they start pummelling each other in a massive free-for-all pillow fight. Spectators might lean forward, coffee forgotten, as feathers fly and more and more people join in. All around the square, others hang out of their windows or stop on the street, transfixed, to watch. After several minutes, the spectacle is over. With cheers and the occasional high-five, the crowd disperses, leaving only destroyed pillows and clouds of fluff in its wake.

This is a flash mob, a large group of people who gather together in a spontaneous activity that lasts a limited amount of time before returning to their regular routines. Technology plays a big role in the creation of a flash mob: select people are texted or emailed, and the message spreads virally until a crowd has grown. But while technology might explain the “how” of flash mobs, it does not explain the “why.” Flash mobs often are captured on video and shared on the internet; frequently they go viral and become well known. So what leads people to want to flock somewhere for a massive pillow fight? Or for a choreographed dance? Or to freeze in place? Why is this appealing? In large part, it is as simple as the reason humans have bonded together around fires for storytelling, or danced together, or joined a community holiday celebration. Humans seek connections and shared experiences. And a flash mob, pillows included, provides a way to make that happen.

12.1.2 Forms of Collective Behaviour

Flash mobs are examples of collective behaviour, non-institutionalized activity in which several people voluntarily engage. Other examples of collective behaviour can include anything from a group of commuters travelling home from work to the trend toward adopting the Justin Bieber hair flip. In short, it can be any group behaviour that is not mandated or regulated by an institution. There are four primary forms of collective behaviour: the crowd, the mass, the public, and social movements.

It takes a fairly large number of people in close proximity to form a crowd (Lofland, 1993). Examples include a group of people attending a Neil Young concert, attending Canada Day festivities, or joining a worship service. Turner and Killian (1993) identified four types of crowds. Casual crowds consist of people who are in the same place at the same time, but who are not really interacting, such as people standing in line at the post office. Conventional crowds are those who come together for a scheduled event, like a religious service or rock concert. Expressive crowds are people who join together to express emotion, often at funerals, weddings, or the like. The final type, acting crowds, focus on a specific goal or action, such as a protest movement or riot.

In addition to the different types of crowds, collective groups can also be identified in two other ways (Lofland, 1993). A mass is a relatively large and dispersed number of people with a common interest, whose members are largely unknown to one another and who are incapable of acting together in a concerted way to achieve objectives. In this sense, the audience of the television show Game of Thrones or of any mass medium (TV, radio, film, books) is a mass. A public, on the other hand, is an unorganized, relatively diffused group of people who share ideas on an issue, such as social conservatives. While these two types of crowds are similar, they are not the same. To distinguish between them, remember that members of a mass share interests whereas members of a public share ideas.

12.1.3 Theoretical Perspectives on Collective Behaviour

Early collective behaviour theories (Blumer, 1969; Le Bon, 1895) focused on the irrationality of crowds. Le Bon saw the tendency for crowds to break into riots or anti-Semitic pogroms as a product of the properties of crowds themselves: anonymity, contagion, and suggestibility. On their own, each individual would not be capable of acting in this manner, but as anonymous members of a crowd they were easily swept up in dynamics that carried them away. Eventually, those theorists who viewed crowds as uncontrolled groups of irrational people were supplanted by theorists who viewed the behaviour of some crowds as the rational behaviour of logical beings.

Emergent-Norm Perspective

Sociologists Ralph Turner and Lewis Killian (1993) built on earlier sociological ideas and developed what is known as emergent norm theory. They believe that the norms experienced by people in a crowd may be disparate and fluctuating. They emphasize the importance of these norms in shaping crowd behaviour, especially those norms that shift quickly in response to changing external factors. Emergent norm theory asserts that, in this circumstance, people perceive and respond to the crowd situation with their particular (individual) set of norms, which may change as the crowd experience evolves. This focus on the individual component of interaction reflects a symbolic interactionist perspective.

For Turner and Killian, the process begins when individuals suddenly find themselves in a new situation, or when an existing situation suddenly becomes strange or unfamiliar. For example, think about human behaviour during Hurricane Katrina. New Orleans was decimated and people were trapped without supplies or a way to evacuate. In these extraordinary circumstances, what outsiders saw as “looting” was defined by those involved as seeking needed supplies for survival. Normally, individuals would not wade into a corner gas station and take canned goods without paying, but given that they were suddenly in a greatly changed situation, they established a norm that they felt was reasonable.

Once individuals find themselves in a situation ungoverned by previously established norms, they interact in small groups to develop new guidelines on how to behave. According to the emergent-norm perspective, crowds are not viewed as irrational, impulsive, uncontrolled groups. Instead, norms develop and are accepted as they fit the situation. While this theory offers insight into why norms develop, it leaves undefined the nature of norms, how they come to be accepted by the crowd, and how they spread through the crowd.

Value-Added Theory

Neil Smelser’s (1962) meticulous categorization of crowd behaviour, called value-added theory, is a perspective within the functionalist tradition based on the idea that several conditions must be in place for collective behaviour to occur. Each condition adds to the likelihood that collective behaviour will occur.

The first condition is structural conduciveness, which describes when people are aware of the problem and have the opportunity to gather, ideally in an open area. Structural strain, the second condition, refers to people’s expectations about the situation at hand being unmet, causing tension and strain. The next condition is the growth and spread of a generalized belief, wherein a problem is clearly identified and attributed to a person or group.

Fourth, precipitating factors spur collective behaviour; this is the emergence of a dramatic event. The fifth condition is mobilization for action, when leaders emerge to direct a crowd to action. The final condition relates to action by the agents of social control. Called social control, it is the only way to end the collective behaviour episode (Smelser, 1962).

Let us consider a hypothetical example of these conditions. In structure conduciveness (awareness and opportunity), a group of students gathers on the campus quad. Structural strain emerges when they feel stress concerning their high tuition costs. If the crowd decides that the latest tuition hike is the fault of the chancellor, and that he or she will lower tuition if they protest, then growth and spread of a generalized belief has occurred. A precipitation factor arises when campus security appears to disperse the crowd, using pepper spray to do so. When the student body president sits down and passively resists attempts to stop the protest, this represents mobilization of action. Finally, when local police arrive and direct students back to their dorms, we have seen agents of social control in action.

While value-added theory addresses the complexity of collective behaviour, it also assumes that such behaviour is inherently negative or disruptive. In contrast, collective behaviour can be non-disruptive, such as when people flood to a place where a leader or public figure has died to express condolences or leave tokens of remembrance. People also forge momentary alliances with strangers in response to natural disasters.

Assembling Perspective

Interactionist sociologist Clark McPhail (1991) developed the assembling perspective, another system for understanding collective behaviour that credited individuals in crowds as rational beings. Unlike previous theories, this theory refocuses attention from collective behaviour to collective action. Remember that collective behaviour is a non-institutionalized gathering, whereas collective action is based on a shared interest. McPhail’s theory focused primarily on the processes associated with crowd behaviour, plus the life cycle of gatherings. He identified several instances of convergent or collective behaviour, as shown on the chart below.

| Type of crowd | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence clusters | Family and friends who travel together | Carpooling parents take several children to the movies |

| Convergent orientation | Group all facing the same direction | A semi-circle around a stage |

| Collective vocalization | Sounds or noises made collectively | Screams on a roller coaster |

| Collective verbalization | Collective and simultaneous participation in a speech or song | Singing “O Canada” at a hockey game |

| Collective gesticulation | Body parts forming symbols | The YMCA dance |

| Collective manipulation | Objects collectively moved around | Holding signs at a protest rally |

| Collective locomotion | The direction and rate of movement to the event | Children running to an ice cream truck |

As useful as this is for understanding the components of how crowds come together, many sociologists criticize its lack of attention on the large cultural context of the described behaviours, instead focusing on individual actions.

12.2 Social Movements

Social movements are purposeful, organized groups striving to work toward a common social goal. While most of us learned about social movements in history classes, we tend to take for granted the fundamental changes they caused — and we may be completely unfamiliar with the trend toward global social movement. But from the anti-tobacco movement that has worked to outlaw smoking in public buildings and raise the cost of cigarettes, to uprisings throughout the Arab world, contemporary movements create social change on a global scale.

12.2.1 Levels of Social Movements

Movements happen in our towns, in our nation, and around the world. The following examples of social movements range from local to global. No doubt you can think of others on all of these levels, especially since modern technology has allowed us a near-constant stream of information about the quest for social change around the world.

Local

Winnipeg’s inner city is well known for its poor indigenous population, low levels of income and education, and concerns about drugs, gangs, and violence. Not surprisingly, it has been home to a number of social movements and grassroots community organizations over time (Silver, 2008). Currently, the Winnipeg Boldness Project is a social movement focused on providing investment in early childhood care in the Point Douglas community to try to break endemic cycles of poverty. Statistics show that 40% of Point Douglas children are not ready for school by age five and one in six are apprehended by child protection agencies. Through programs that support families and invest in early childhood development, children could be prepared for school and not be forced into the position of having to catch up to their peers (Roussin, Gill, and Young, 2014). The organization seeks to “create new conditions to dramatically transform the well-being of young children in Point Douglas” (Winnipeg Boldness Project, 2014).

Regional

At the other end of the political spectrum from the Winnipeg Boldness Project is the legacy of the numerous conservative and extreme right social movements of the 1980s and 1990s that advocated the independence of western Canada from the rest of the country. The Western Canada Concept, Western Independence Party, Confederation of Regions Party, and Western Block were all registered political parties representing social movements of western alienation. The National Energy Program of 1980 was one of the key catalysts for this movement because it was seen as a way of securing cheap oil and gas resources for central Canada at the expense of Alberta. However, the seeds of western alienation developed much earlier with the sense that Canadian federal politics was dominated by the interests of Quebec and Ontario. One of the more infamous leaders of the Western Canada Concept was Doug Christie who made a name for himself as the lawyer who defended the Holocaust-deniers Jim Keegstra and Ernst Zundel in well-publicized trials. Part of the program of the Western Canada Concept, aside from western independence, was to end non-European immigration to Canada and preserve Christian and European culture. In addition to these extreme-right concerns, however, were many elements of democratic reform and fiscal conservativism, such as mandatory balanced-budget legislation and provisions for referenda and recall (Western Canada Concept, N.d.), which later became central to the Reform Party. The Reform Party was western based but did not seek western independence. Rather it sought to transform itself into a national political party eventually forming the Canadian Alliance Party with other conservative factions. The Canadian Alliance merged with the Progressive Conservative Party to form the Conservative Party of Canada.

National

A prominent national social movement in recent years is Idle No More. A group of indigenous women organized an event in Saskatchewan in November 2012 to protest the Conservative government’s C-45 omnibus bill. The contentious features of the bill that concerned indigenous people were the government’s lack of consultation with them in provisions that changed the Indian Act, the Navigation Protection Act, and the Environmental Assessment Act. A month later Idle No More held a national day of action and Chief Theresa Spence of the Attawapiskat First Nation began a 43-day hunger strike on an island in the Ottawa River near Parliament Hill. The hunger strike galvanized national public attention on indigenous issues, and numerous protest events such as flash mobs and temporary blockades were organized around the country. One of Chief Spence’s demands was that a meeting be set up with the prime minister and the Governor General to discuss indigenous issues. The inclusion of the Governor General — the Queen’s representative in Canada — proved to be the sticking point in arranging this meeting, but was central to Idle No More’s claims that indigenous sovereignty and treaty negotiations were matters whose origins preceded the establishment of the Canadian state. Chief Spence ended her hunger strike with the signing of a 13-point declaration that demanded commitments from the government to review Bills C-45 and C-38, ensure indigenous consultation on government legislation, initiate an enquiry into missing indigenous women, and improve treaty negotiations, indigenous housing, and education, among other commitments (CBC, 2013a; 2013b).

Comparisons between Idle No More and the recent Occupy Movement emphasized the diffuse, grassroots natures of the movements and their non-hierarchical structures. Idle No More emerged outside, and in some respects in opposition to, the Assembly of First Nations. It was more focused than the Occupy Movement in the sense that it developed in response to particular legislation (Bill C-45), but as it grew it became both broader in its concerns and more radical in its demands for indigenous sovereignty and self-determination. It was also seen to have the same organizational problems as the Occupy movement in that the goals of the movement were left more or less open, the leadership remained decentralized, and no formal decision-making structures were established. Some members of the Idle No More movement were satisfied with the 13-point declaration, while others sought more radical solutions of self-determination outside the traditional pattern of negotiating with the federal government. It is not clear that Idle No More, as a social movement, will move toward a more conventional social-movement structure or whether it will dissipate and be replaced by other indigenous movements (CBC, 2013c; Gollom, 2013). Taiaiake Alfred’s post-mortem of the movement was that “the limits to Idle No More are clear, and many people are beginning to realize that the kind of movement we have been conducting under the banner of Idle No More is not sufficient in itself to decolonize this country or even to make meaningful change in the lives of people” (2013).

Global

Despite their successes in bringing forth change on controversial topics, social movements are not always about volatile politicized issues. For example, the global movement called Slow Food focuses on how we eat as means of addressing contemporary quality-of-life issues. Slow Food, with the slogan “Good, Clean, Fair Food,” is a global grassroots movement claiming supporters in 150 countries. The movement links community and environmental issues back to the question of what is on our plates and where it came from. Founded in 1989 in response to the increasing existence of fast food in communities that used to treasure their culinary traditions, Slow Food works to raise awareness of food choices (Slow Food, 2011). With more than 100,000 members in 1,300 local chapters, Slow Food is a movement that crosses political, age, and regional lines.

12.2.2 Types of Social Movements

We know that social movements can occur on the local, national, or even global stage. Are there other patterns or classifications that can help us understand them? Sociologist David Aberle (1966) addresses this question, developing categories that distinguish among social movements based on what they want to change and how much change they want. Reform movements seek to change something specific about the social structure. Examples include anti-nuclear groups, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), and the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (NAC). Revolutionary movements seek to completely change every aspect of society. These would include Cuban 26th of July Movement (under Fidel Castro), the 1960s counterculture movement, as well as anarchist collectives. Redemptive movements are “meaning seeking,” and their goal is to provoke inner change or spiritual growth in individuals. Organizations pushing these movements might include Alcoholics Anynymous, New Age, or Christian fundamentalist groups. Alternative movements are focused on self-improvement and limited, specific changes to individual beliefs and behaviour. These include groups like the Slow Food movement, Planned Parenthood, and barefoot jogging advocates. Resistance movements seek to prevent or undo change to the social structure. The Ku Klux Klan and pro-life movements fall into this category.

12.2.3 Stages of Social Movements

Later sociologists studied the life cycle of social movements — how they emerge, grow, and in some cases, die out. Blumer (1969) and Tilly (1978) outline a four-stage process. In the preliminary stage, people become aware of an issue and leaders emerge. This is followed by the coalescence stage when people join together and organize in order to publicize the issue and raise awareness. In the institutionalization stage, the movement no longer requires grassroots volunteerism: it is an established organization, typically peopled with a paid staff. When people fall away, adopt a new movement, the movement successfully brings about the change it sought, or people no longer take the issue seriously, the movement falls into the decline stage. Each social movement discussed earlier belongs in one of these four stages. Where would you put them on the list?

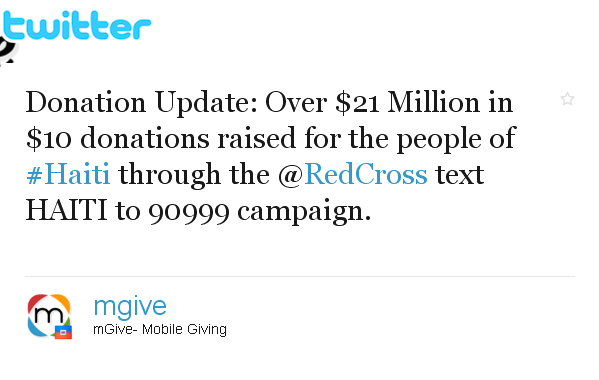

12.2.4 Social Media and Social Change: A Match Made in Heaven

Chances are you have been asked to tweet, friend, like, or donate online for a cause. Maybe you were one of the many people who, in 2010, helped raise over $3 million in relief efforts for Haiti through cell phone text donations. Or maybe you follow political candidates on Twitter and retweet their messages to your followers. Perhaps you have “liked” a local nonprofit on Facebook, prompted by one of your neighbours or friends liking it too. Nowadays, woven throughout our social media activities, are social movements. After all, social movements start by activating people.

Referring to the ideal type stages discussed above, you can see that social media has the potential to dramatically transform how people get involved. Look at the first stage, the preliminary stage: people become aware of an issue and leaders emerge. Imagine how social media speeds up this step. Suddenly, a shrewd user of Twitter can alert thousands of followers about an emerging cause or an issue on his or her mind. Issue awareness can spread at the speed of a click, with thousands of people across the globe becoming informed at the same time. In a similar vein, those who are savvy and engaged with social media emerge as leaders. Suddenly, you do not need to be a powerful public speaker. You do not even need to leave your house. You can build an audience through social media without ever meeting the people you are inspiring.

At the next stage, the coalescence stage, social media also is transformative. Coalescence is the point when people join together to publicize the issue and get organized. U.S. President Obama’s 2008 campaign became a case study in organizing through social media. Using Twitter and other online tools, the campaign engaged volunteers who had typically not bothered with politics, and empowered those who were more active to generate still more activity. It is no coincidence that Obama’s earlier work experience included grassroots community organizing. What is the difference between this type of campaign and the work that political activists did in neighbourhoods in earlier decades? The ability to organize without regard to geographical boundaries becomes possible using social media. In 2009, when student protests erupted in Tehran, social media was considered so important to the organizing effort that the U.S. State Department actually asked Twitter to suspend scheduled maintenance so that a vital tool would not be disabled during the demonstrations.

So what is the real impact of this technology on the world? Did Twitter bring down Mubarak in Egypt? Author Malcolm Gladwell (2010) does not think so. In an article in New Yorker magazine, Gladwell tackles what he considers the myth that social media gets people more engaged. He points out that most of the tweets relating to the Iran protests were in English and sent from Western accounts (instead of people on the ground). Rather than increasing engagement, he contends that social media only increases participation; after all, the cost of participation is so much lower than the cost of engagement. Instead of risking being arrested, shot with rubber bullets, or sprayed with fire hoses, social media activists can click “like” or retweet a message from the comfort and safety of their desk (Gladwell, 2010).

Sociologists have identified high-risk activism, such as the civil rights movement, as a “strong-tie” phenomenon, meaning that people are far more likely to stay engaged and not run home to safety if they have close friends who are also engaged. The people who dropped out of the movement — who went home after the danger got too great — did not display any less ideological commitment. They lacked the strong-tie connection to other people who were staying. Social media, by its very makeup, is “weak-tie” (McAdam and Paulsen, 1993). People follow or friend people they have never met. While these online acquaintances are a source of information and inspiration, the lack of engaged personal contact limits the level of risk we will take on their behalf.

12.2.5 Theoretical Perspectives on Social Movements

Most theories of social movements are called collective action theories, indicating the purposeful nature of this form of collective behaviour. The following three theories are but a few of the many classic and modern theories developed by social scientists. Resource mobilization theory focuses on the purposive, organizational strategies that social movements need to engage in to successfully mobilize support, compete with other social movements and opponents, and present political claims and grievances to the state. Framing theory focuses on the way social movements make appeals to potential supporters by framing or presenting their issues in a way that aligns with commonly held values, beliefs, and commonsense attitudes. New social movement theory focuses on the unique qualities that define the “newness” of postmaterialist social movements like the Green, feminist, and peace movements.

Resource Mobilization

Social movements will always be a part of society as long as there are aggrieved populations whose needs and interests are not being satisfied. However, grievances do not become social movements unless social movement actors are able to create viable organizations, mobilize resources, and attract large-scale followings. As people will always weigh their options and make rational choices about which movements to follow, social movements necessarily form under finite competitive conditions: competition for attention, financing, commitment, organizational skills, etc. Not only will social movements compete for our attention with many other concerns — from the basic (our jobs or our need to feed ourselves) to the broad (video games, sports, or television), but they also compete with each other. For any individual, it may be a simple matter to decide you want to spend your time and money on animal shelters and Conservative Party politics versus homeless shelters and the New Democratic Party. The question is, however, which animal shelter or which Conservative candidate? To be successful, social movements must develop the organizational capacity to mobilize resources (money, people, and skills) and compete with other organizations to reach their goals.

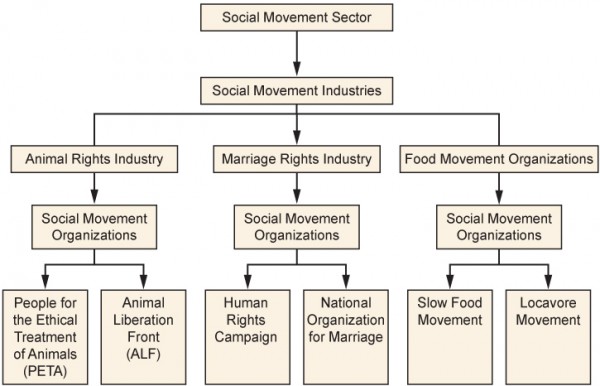

McCarthy and Zald (1977) conceptualize resource mobilization theory as a way to explain a movement’s success in terms of its ability to acquire resources and mobilize individuals to achieve goals and take advantage of political opportunities. For example, PETA, a social movement organization, is in competition with Greenpeace and the Animal Liberation Front (ALF), two other social movement organizations. Taken together, along with all other social movement organizations working on animals rights issues, these similar organizations constitute a social movement industry. Multiple social movement industries in a society, though they may have widely different constituencies and goals, constitute a society’s social movement sector. Every social movement organization (a single social movement group) within the social movement sector is competing for your attention, your time, and your resources. The chart in Figure 21.9 shows the relationship between these components.

Framing/Frame Analysis

The sudden emergence of social movements that have not had time to mobilize resources, or vice versa, the failure of well-funded groups to achieve effective collective action, calls into question the emphasis on resource mobilization as an adequate explanation for the formation of social movements. Over the past several decades, sociologists have developed the concept of frames to explain how individuals identify and understand social events and which norms they should follow in any given situation (Benford and Snow, 2000; Goffman, 1974; Snow et al., 1986). A frame is a way in which experience is organized conceptually. Imagine entering a restaurant. Your “frame” immediately provides you with a behaviour template. It probably does not occur to you to wear pajamas to a fine dining establishment, throw food at other patrons, or spit your drink onto the table. However, eating food at a sleepover pizza party provides you with an entirely different behaviour template. It might be perfectly acceptable to eat in your pajamas, and maybe even throw popcorn at others or guzzle drinks from cans. Similarly, social movements must actively engage in realigning collective social frames so that the movements’ interests, ideas, values, and goals become congruent with those of potential members. The movements’ goals have to make sense to people to draw new recruits into their organizations.

Successful social movements use three kinds of frames (Snow and Benford, 1988) to further their goals. The first type, diagnostic framing, states the social movement problem in a clear, easily understood way. When applying diagnostic frames, there are no shades of grey: instead, there is the belief that what “they” do is wrong and this is how “we” will fix it. The anti-gay marriage movement is an example of diagnostic framing with its uncompromising insistence that marriage is only between a man and a woman. Any other concept of marriage is framed as sinful or immoral. Prognostic framing, the second type, offers a solution and states how it will be implemented. When looking at the issue of pollution as framed by the environmental movement, for example, prognostic frames would include direct legal sanctions and the enforcement of strict government regulations or the imposition of carbon taxes or cap-and-trade mechanisms to make environmental damage more costly. As you can see, there may be many competing prognostic frames even within social movements adhering to similar diagnostic frames. Finally, motivational framing is the call to action: what should you do once you agree with the diagnostic frame and believe in the prognostic frame? These frames are action-oriented. In the indigenous justice movement, a call to action might encourage you to join a blockade on contested indigenous treaty land or contact your local MP to express your viewpoint that indigenous treaty rights be honoured.

With so many similar diagnostic frames, some groups find it best to join together to maximize their impact. When social movements link their goals to the goals of other social movements and merge into a single group, a frame alignment process (Snow et al., 1986) occurs — an ongoing and intentional means of recruiting a diversity of participants to the movement. For example, Carroll and Ratner (1996) argue that using a social justice frame makes it possible for a diverse group of social movements — union movements, environmental movements, indigenous justice movements, gay rights movements, anti-poverty movements, etc. — to form effective coalitions even if their specific goals do not typically align.

This frame alignment process involves four aspects: bridging, amplification, extension, and transformation. Bridging describes a “bridge” that connects uninvolved individuals and unorganized or ineffective groups with social movements that, though structurally unconnected, nonetheless share similar interests or goals. These organizations join together creating a new, stronger social movement organization. Can you think of examples of different organizations with a similar goal that have banded together?

In the amplification model, organizations seek to expand their core ideas to gain a wider, more universal appeal. By expanding their ideas to include a broader range, they can mobilize more people for their cause. For example, the Slow Food movement extends its arguments in support of local food to encompass reduced energy consumption and reduced pollution, plus reduced obesity from eating more healthfully, and other benefits.

In extension, social movements agree to mutually promote each other, even when the two social movement organization’s goals do not necessarily relate to each other’s immediate goals. This often occurs when organizations are sympathetic to each others’ causes, even if they are not directly aligned, such as women’s equal rights and the civil rights movement.

Transformation involves a complete revision of goals. Once a movement has succeeded, it risks losing relevance. If it wants to remain active, the movement has to change with the transformation or risk becoming obsolete. For instance, when the women’s suffrage movement gained women the right to vote, they turned their attention to equal rights and campaigning to elect women. In short, it is an evolution to the existing diagnostic or prognostic frames generally involving a total conversion of movement.

New Social Movement Theory

New social movement theory emerged in the 1970s to explain the proliferation of postindustrial, quality-of-life movements that are difficult to analyze using traditional social movement theories (Melucci, 1989). Rather than being based on the grievances of particular groups striving to influence political outcomes or redistribute material resources, new social movements (NSMs) like the peace and disarmament, environmental, and feminist movements focus on goals of autonomy, identity, self-realization, and quality-of-life issues. As the German Green Party slogan of the 1980s suggests — “We are neither right nor left, but ahead” — the appeal of the new social movements also tends to cut across traditional class, party politics, and socioeconomic affiliations to politicize aspects of everyday life traditionally seen as outside politics. Moreover, the movements themselves are more flexible, diverse, shifting, and informal in participation and membership than the older social movements, often preferring to adopt nonhierarchical modes of organization and unconventional means of political engagement (such as direct action).

Melucci (1994) argues that the commonality that designates these diverse social movements as “new” is the way in which they respond to systematic encroachments on the lifeworld, the shared inter-subjective meanings and common understandings that form the backdrop of our daily existence and communication. The dimensions of existence that were formally considered private (e.g., the body, sexuality, interpersonal affective relations), subjective (e.g., desire, motivation, and cognitive or emotional processes), or common (e.g., nature, urban spaces, language, information, and communicational resources) are increasingly subject to social control, manipulation, commodification, and administration. However, as Melucci (1994) argues,

These are precisely the areas where individuals and groups lay claim to their autonomy, where they conduct their search for identity…and construct the meaning of what they are and what they do (pp. 101-102).

12.3 Social Change

Collective behaviour and social movements are just two of the forces driving social change, which is the change in society created through social movements as well as external factors like environmental shifts or technological innovations. Essentially, any disruptive shift in the status quo, be it intentional or random, human-caused or natural, can lead to social change. Below are some of the likely causes.

12.3.1 Causes of Social Change

Changes to technology, social institutions, population, and the environment, alone or in some combination, create change. Below, we will discuss how these act as agents of social change and we’ll examine real-world examples. We will focus on four agents of change recognized by social scientists: technology, social institutions, population, and the environment.

Technology

Some would say that improving technology has made our lives easier. Imagine what your day would be like without the internet, the automobile, or electricity. In The World Is Flat, Thomas Friedman (2005) argues that technology is a driving force behind globalization, while the other forces of social change (social institutions, population, environment) play comparatively minor roles. He suggests that we can view globalization as occurring in three distinct periods. First, globalization was driven by military expansion, powered by horsepower and windpower. The countries best able to take advantage of these power sources expanded the most, exerting control over the politics of the globe from the late 15th century to around the year 1800. The second shorter period, from approximately 1800 CE to 2000 CE, consisted of a globalizing economy. Steam and rail power were the guiding forces of social change and globalization in this period. Finally, Friedman brings us to the post-millennial era. In this period of globalization, change is driven by technology, particularly the internet (Friedman, 2005).

But also consider that technology can create change in the other three forces social scientists link to social change. Advances in medical technology allow otherwise infertile women to bear children, indirectly leading to an increase in population. Advances in agricultural technology have allowed us to genetically alter and patent food products, changing our environment in innumerable ways. From the way we educate children in the classroom to the way we grow the food we eat, technology has impacted all aspects of modern life.

Of course there are drawbacks. The increasing gap between the technological haves and have-nots — sometimes called the digital divide — occurs both locally and globally. Further, there are added security risks: the loss of privacy, the risk of total system failure (like the Y2K panic at the turn of the millennium), and the added vulnerability created by technological dependence. Think about the technology that goes into keeping nuclear power plants running safely and securely. What happens if an earthquake or other disaster, as in the case of Japan’s Fukushima plant, causes the technology to malfunction, not to mention the possibility of a systematic attack to our nation’s relatively vulnerable technological infrastructure?

Social Institutions

Each change in a single social institution leads to changes in all social institutions. For example, the industrialization of society meant that there was no longer a need for large families to produce enough manual labour to run a farm. Further, new job opportunities were in close proximity to urban centres where living space was at a premium. The result is that the average family size shrunk significantly.

This same shift toward industrial corporate entities also changed the way we view government involvement in the private sector, created the global economy, provided new political platforms, and even spurred new religions and new forms of religious worship like Scientology. It has also informed the way we educate our children: originally schools were set up to accommodate an agricultural calendar so children could be home to work the fields in the summer, and even today, teaching models are largely based on preparing students for industrial jobs, despite that being an outdated need. As this example illustrates, a shift in one area, such as industrialization, means an interconnected impact across social institutions.

Population

Population composition is changing at every level of society. Births increase in one nation and decrease in another. Some families delay childbirth while others start bringing children into their fold early. Population changes can be due to random external forces, like an epidemic, or shifts in other social institutions, as described above. But regardless of why and how it happens, population trends have a tremendous interrelated impact on all other aspects of society.

In Canada, we are experiencing an increase in our senior population as baby boomers begin to retire, which will in turn change the way many of our social institutions are organized. For example, there is an increased demand for housing in warmer climates, a massive shift in the need for elder care and assisted-living facilities, and growing awareness of elder abuse. There is concern about labour shortages as boomers retire, not to mention the knowledge gap as the most senior and accomplished leaders in different sectors start to leave. Further, as this large generation leaves the workforce, the loss of tax income and pressure on pension and retirement plans means that the financial stability of the country is threatened.

Globally, often the countries with the highest fertility rates are least able to absorb and attend to the needs of a growing population. Family planning is a large step in ensuring that families are not burdened with more children than they can care for. On a macro level, the increased population, particularly in the poorest parts of the globe, also leads to increased stress on the planet’s resources.

The Environment

Turning to human ecology, we know that individuals and the environment affect each other. As human populations move into more vulnerable areas, we see an increase in the number of people affected by natural disasters, and we see that human interaction with the environment increases the impact of those disasters. Part of this is simply the numbers: the more people there are on the planet, the more likely it is that people will be impacted by a natural disaster.

But it goes beyond that. We face a combination of too many people and the increased demands these numbers make on the Earth. As a population, we have brought water tables to dangerously low levels, built up fragile shorelines to increase development, and irrigated massive crop fields with water brought in from far away. How can we be surprised when homes along coastlines are battered and droughts threaten whole towns? The year 2011 holds the unwelcome distinction of being a record year for billion-dollar weather disasters, with about a dozen falling into that category. From twisters and floods to snowstorms and droughts, the planet is making our problems abundantly clear (CBS News, 2011). These events have birthed social movements and are bringing about social change as the public becomes educated about these issues.

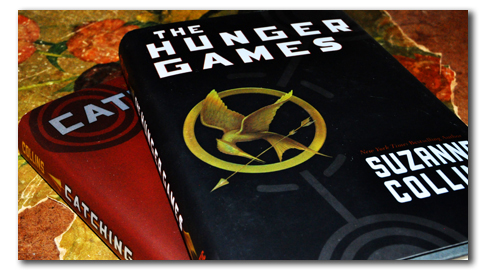

12.3.2 Our Dystopian Future: From A Brave New World to The Hunger Games

Humans have long been interested in science fiction and space travel, and many of us are eager to see the invention of jet packs and flying cars. But part of this futuristic fiction trend is much darker and less optimistic. In 1932, when Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World was published, there was a cultural trend toward seeing the future as golden and full of opportunity. In his novel set in 2540, there is a more frightening future. Since then, there has been an ongoing stream of dystopian novels, or books set in the future after some kind of apocalypse has occurred and when a totalitarian and restrictive government has taken over. These books have been gaining in popularity recently, especially among young adult readers. And while the adult versions of these books often have a grim or dismal ending, the youth-geared versions usually end with some promise of hope.

So what is it about our modern times that makes looking forward so fearsome? Take the example of author Suzanne Collins’s hugely popular Hunger Games trilogy for young adults. The futuristic setting isn’t given a date, and the locale is Panem, a transformed version of North America with 12 districts ruled by a cruel and dictatorial capitol. The capitol punishes the districts for their long-ago attempt at rebellion by forcing an annual Hunger Game, where two children from each district are thrown into a created world where they must fight to the death. Connotations of gladiator games and video games come together in this world, where the government can kill people for their amusement, and the technological wonders never cease. From meals that appear at the touch of a button to mutated government-built creatures that track and kill, the future world of Hunger Games is a mix of modernization fantasy and nightmare.

When thinking about modernization theory and how it is viewed today by both functionalists and conflict theorists, it is interesting to look at this world of fiction that is so popular. When you think of the future, do you view it as a wonderful place, full of opportunity? Or as a horrifying dictatorship sublimating the individual to the good of the state? Do you view modernization as something to look forward to or something to avoid? And which media has influenced your view?

12.3.3 Modernization

Modernization describes the processes that increase the amount of specialization and differentiation of structure in societies resulting in the move from an undeveloped society to developed, technologically driven society (Irwin, 1975). By this definition, the level of modernity within a society is judged by the sophistication of its technology, particularly as it relates to infrastructure, industry, and the like. However, it is important to note the inherent ethnocentric bias of such assessment. Why do we assume that those living in semi-peripheral and peripheral nations would find it so wonderful to become more like the core nations? Is modernization always positive?

One contradiction of all kinds of technology is that they often promise time-saving benefits, but somehow fail to deliver. How many times have you ground your teeth in frustration at an internet site that refused to load or at a dropped call on your cell phone? Despite time-saving devices such as dishwashers, washing machines, and, now, remote control vacuum cleaners, the average amount of time spent on housework is the same today as it was 50 years ago. And the dubious benefits of 24/7 email and immediate information have simply increased the amount of time employees are expected to be responsive and available. While once businesses had to travel at the speed of the Canadian postal system, sending something off and waiting until it was received before the next stage, today the immediacy of information transfer means there are no such breaks.

Further, the internet bought us information, but at a cost. The morass of information means that there is as much poor information available as trustworthy sources. There is a delicate line to walk when core nations seek to bring the assumed benefits of modernization to more traditional cultures. For one, there are obvious pro-capitalist biases that go into such attempts, and it is short-sighted for Western governments and social scientists to assume all other countries aspire to follow in their footsteps. Additionally, there can be a kind of neo-liberal defence of rural cultures, ignoring the often crushing poverty and diseases that exist in peripheral nations and focusing only on a nostalgic mythology of the happy peasant. It takes a very careful hand to understand both the need for cultural identity and preservation as well as the hopes for future growth.

Key Terms

acting crowds: Crowds of people who are focused on a specific action or goal.

alternative movements: Social movements that limit themselves to self-improvement changes in individuals.

assembling perspective: A theory that credits individuals in crowds as behaving as rational thinkers and views crowds as engaging in purposeful behaviour and collective action.

casual crowds: People who share close proximity without really interacting.

collective behaviour: A non-institutionalized activity in which several people voluntarily engage.

conventional crowds: People who come together for a regularly scheduled event.

crowd: A fairly large number of people sharing close proximity.

diagnostic framing: When the social problem is stated in a clear, easily understood manner.

digital divide: The increasing gap between the technological haves and have-nots.

emergent norm theory: A perspective that emphasizes the importance of social norms in crowd behaviour.

expressive crowds: Crowds that share opportunities to express emotions.

flash mob: A large group of people who gather together in a spontaneous activity that lasts a limited amount of time.

frame: A way in which experience is organized conceptually.

frame alignment process: Using bridging, amplification, extension, and transformation as an ongoing and intentional means of recruiting participants to a movement.

lifeworld: The shared inter-subjective meanings and common understandings that form the backdrop of our daily existence and communication.

mass: A relatively large group with a common interest, even if the group members may not be in close proximity.

modernization: The process that increases the amount of specialization and differentiation of structure in societies.

motivational framing: A call to action.

new social movement theory: Theory that attempts to explain the proliferation of postindustrial and postmodern movements that are difficult to understand using traditional social movement theories.

prognostic framing: When social movements state a clear solution and a means of implementation.

public: An unorganized, relatively diffuse group of people who share ideas.

redemptive movements: Movements that work to promote inner change or spiritual growth in individuals.

reform movements: Movements that seek to change something specific about the social structure.

resistance movements: movements that seek to prevent or undo change to the social structure.

resource mobilization theory: Theory that explains social movements’ success in terms of their ability to acquire resources and mobilize individuals.

revolutionary movements: Movements that seek to completely change every aspect of society.

social change: The change in a society created through social movements as well as through external factors like environmental shifts or technological innovations.

social movement: A purposeful, organized group hoping to work toward a common social goal.

social movement industry: The collection of the social movement organizations that are striving toward similar goal.

social movement organization: A single social movement group.

social movement sector: The multiple social movement industries in a society, even if they have a wide variety of constituents and goals.

value-added theory: A functionalist perspective theory that posits that several preconditions must be in place for collective behaviour to occur.

12.4 References

Aberle, David. (1966). The Peyote religion among the Navaho. Chicago: Aldine.

Alfred, Taiaiake. (2013, January 27). Idle no more: The Indigenous Peoples’ movement. Idlenomore.tumblr.com. Retrieved August 13, 2014, from http://idlenomore.tumblr.com/post/41651870376/taiaiake-alfred-idle-no-more-and-indigenous-nationhood.

Benford, Robert, and David Snow. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26:611–639.

Blumer, Herbert. (1969). Collective Behavior. In A.M. Lee (Ed.), Principles of Sociology (pp. 67–121). New York: Barnes and Noble.

Carroll, William and Robert Ratner. (1996). Master frames and counter-hegemony: Political sensibilities in contemporary social movements. Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 33: 407-435.

CBC. (2013a, January 5). 9 questions about Idle No More. CBC News. Retrieved August 13, 2014, from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/9-questions-about-idle-no-more-1.1301843.

CBC. (2013b, January 23). Chief Theresa Spence to end hunger strike today. CBC News. Retrieved August 13, 2014, from http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/chief-theresa-spence-to-end-hunger-strike-today-1.1341571.

CBC. (2013c, November 10) Idle No More anniversary sees divisions Emerging. Huffington Post. Retrieved August 13, 2014, from http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/11/10/idle-no-more-anniversary_n_4250345.html?utm_hp_ref=idle-no-more.

CBS News. (2011, December 11). Record year for billion dollar disasters.. CBS News. . Retrieved December 26, 2011, from http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-201_162-57339130/record-year-for-billion-dollar-disasters

Gladwell, Malcolm. (2010, October 4). Small change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted. The New Yorker. Retrieved December 23, 201, from http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/10/04/101004fa_fact_gladwell?currentPage=all.

Goffman, Erving. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gollom, Mark. (2013, January 8). Is Idle No More the new Occupy Wall Street? CBC News. Retrieved August 13, 2014, from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/is-idle-no-more-the-new-occupy-wall-street-1.1397642.

Irwin, Patrick. (1975). An operational definition of societal modernization. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 23:595–613.

Le Bon, Gustave. (1960). The crowd: A study of the popular mind. New York: Viking Press. (Original work published 1895)

Lofland, John. (1993). Collective behavior: The elementary forms. In Russel Curtis and Benigno Aguirre (Eds.), Collective behavior and social movements (pp. 70–75). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

McAdam, Doug and Ronnelle Paulsen. (1993). Specifying the relationship between social ties and activism. American Journal of Sociology, 99:640–667.

McCarthy, John D. and Mayer N. Zald. (1977). Resource mobilization and social movements: A partial theory. American Journal of Sociology, 82:1212–1241.

McPhail, Clark. (1991). The myth of the madding crowd. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Melucci, Alberto. (1989). Nomads of the present. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Melucci, Alberto. (1994). A strange kind of newness: What’s “new” in new social movements? In Enrique Larana, Hank Johnston, and Joseph Gusfield (Eds), New Social Movements (pp. 101-130). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Miller, Laura. (2010, June 14). Fresh hell: What’s behind the boom in dystopian fiction for young readers? The New Yorker. Retrieved December 26, 2011, from http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/atlarge/2010/06/14/100614crat_atlarge_miller.

NAACP. (2011). 100 Years of History. Retrieved December 21, 2011, from http://www.naacp.org/pages/naacp-history.

Roussin, Diane, Ian Gill and Ric Young. (2014, March 29). A big, bold plan: project aims to transform downtrodden Winnipeg neighbourhood. Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved August 10, 2014, from http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/a-big-bold-plan-253010241.html.

Silver, Jim. (2008). The inner cities of Saskatoon and Winnipeg: A new and distinctive form of development. [PDF] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. January. Retrieved August 10, 2014, from http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/Manitoba_Pubs/2008/Inner_Cities_of_Saskatoon_and_Winnipeg.pdf

Slow Food. (2011). Slow food international: Good, clean, and fair food. Retrieved December 28, 2011, from http://www.slowfood.com.

Smelser, Neil J. (1963). Theory of collective behavior. New York: Free Press.

Snow, David, E. Burke Rochford, Jr., Steven , and Robert Benford. (1986). Frame alignment processes, micromobilization, and movement participation. American Sociological Review, 51:464–481.

Snow, David A. and Robert D. Benford. (1988). Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. International Social Movement Research, 1:197–217.

Tilly, Charles. (1978). From mobilization to revolution. New York: Mcgraw-Hill College.

Turner, Ralph and Lewis M. Killian. (1993). Collective behavior. (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N. J., Prentice Hall.

Western Canada Concept. (N.d.). Western Canada Concept [website]. Retrieved August 10, 2014, from http://www.westcan.org/.

Winnipeg Boldness Project. (2014). Boldness. Winnipeg Boldness Project. Retrieved August 10, 2014, from http://winnipegboldness.ca/.