The Flipped Classroom

Helen Chang; Dorie-Anna Dueck; and Joelle McBain

Description

The 2020 pandemic has forced many of us to come up with new and creative ways in order to educate our students. Much of learning has moved to an online format with students at home watching videos of PowerPoints, or in synchronous sessions with an instructor. We need to find new ways to engage our students. One approach that can be quite useful is the Flipped Classroom. Lewis, Chen, and Relan (2018) define a Flipped Classroom as “an instructional model in which the traditional lecture is a student’s homework and in-class time is spent on active, inquiry-based learning facilitated by an instructor”. (p. 299) This means that instead of sitting in a classroom watching a PowerPoint and listening to a lecture, the student does some learning at home and then the following day participates in an interactive session. The home learning (previously homework) can take on many different forms. It can be a PowerPoint that an instructor has made previously, or reading from a textbook, but Quigley (2013) discusses in his LinkedIn Education seminar that videos can be a powerful tool for students to use. They are already watching videos, so it might as well be an interesting educational video applicable to what the instructor wants to teach. He discusses that there are many platforms that have ready- made educational videos that can be utilized for this purpose.

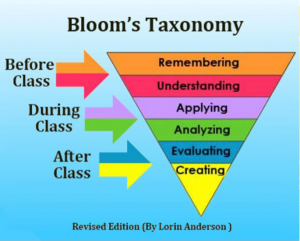

The Flipped Classroom allows for Bloom’s Taxonomy to be turned right on its head with the higher levels now being used for in-classroom time (OMERAD, 2020). Lower levels such as Remembering, Understanding can be done beforehand on the student’s own time, the middle and upper levels can be done during and after class, leading to greater mastery of the content.

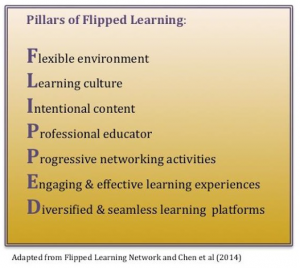

The Flipped Learning Network describes the essentials for what they consider to be Flipped Learning. (Sams, A., Bergmann, J., Daniels, K,. Bennett, B., Marcshall, H. W., Arfstrom, K.M. 2014) They note that there are four pillars that must exist in order to have Flipped Learning, and not just a Flipped Classroom. Those are: a Flexible environment, appropriate Learning culture, Intentional content, and a Professional educator. For a Flexible environment, both the space and expectations need to be flexible. Often instructors will rearrange the working space to assist group work. Additionally, the instructor should be flexible in their expectations of the students regarding the timelines or assessments. The Appropriate Learning culture means that there is a purposeful move to active learning by the student. Where the teacher is no longer the centre of attention, but merely a helper and the instruction is learner centered. With Flipped Learning, the content must be Intentional in that the educator must decide what the students should do/learn on their own, and what then will take place in the classroom time to build on this. Finally, the Professional educator must continue to observe, assist, and provide feedback to the students.

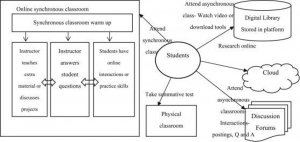

However, Chen, Wang, Kinshuk and Chen (2014) felt that this model needed to be revised and they added three additional pillars: Progressive networking activities, Engaging and effective learning experiences, and Diversified and seamless learning platforms. By adding these additional pillars, they describe what they term as the Holistic Flipped Classroom. They had the entire classroom on an online platform and could monitor when the students logged on to complete the pre-synchronous sessions. This way, they describe that everything is considered the classroom, not just the physical classroom. While this approach may not be needed all of the time, it certainly gives us a way to approach the classroom in the time of the Pandemic and beyond.

Learning Environments

Where can a flipped classroom be applied in a learning environment? During the first two years of medical school, students are immersed in the study of intense learning in various subject content. The traditional didactic lecture has been used for decades to provide this essential foundational medical knowledge. This approach is a teacher-centered passive learning environment and is considered only a transmission of knowledge from the teacher to the student. There are minimal allowances for students to actively engage with the material presented. In Quigley’s LinkedIn video seminar (2013), between 20-80% of this content is absorbed, and without a clinical context, students are unable to retain the information. However, as theories of teaching have evolved, so too has the recognition of a need to incorporate newer learning strategies into the classroom.

The Flipped Classroom (FC) is an innovative approach to improving the learning experience for undergraduate medical students, and its application is relatively new. Prober and Khan (2012) first published a study on its incorporation in medical education. Since then, it has more commonly found footing during the first two years of preclinical study, where the application in the classroom can be quite extensive. This includes the basic sciences (biochemistry, genetics, anatomy and epidemiology), and clinical subject matter (radiology, geriatric medicine, humanities, rheumatology and surgery) (Ramnanan & Pound, 2017). A high degree of rapid competency is required in content, but can a FC lead to improvement in the quantitative makers of student performance?

There is a paucity of robust research documenting this improvement, and published studies are prospective or retrospective only. According to Ramnanan and Pound (2017), after conducting a review of 26 articles, the results are inconsistent. For instance, in one study, examination results were improved in neuroanatomy and obstetrics-gynecology compared to historical controls with traditional teacher-centered learning. However, in another report looking at neuroanatomy competency, there was no improvement in tested knowledge with a FC compared to the traditional learning environment (Whillier and Lystad, 2015). In other preclinical classrooms, there was no improvement in epidemiology or hematology (Ramnanan and Pound, 2017).

There has been less momentum in the application of the FC in the clinical clerkship curriculum. Recently, a group from Stanford (Lieber et al, 2016) prospectively evaluated a replacement of the traditional surgical clerkship rotation with a comprehensive FC approach. Students in the FC cohort were compared to historical controls of students who received the traditional lecture-based approach. Disappointingly, there was no significant difference in the mean score on the quantitative National Board of Medical Examiners Surgical Shelf Examination. It is thought that the FC surgical training curriculum is actually not being accurately tested on this formal exam, and therefore, the absence of a formal objective comparison between the traditional and FC cohorts was not possible, leading to these negative results.

Tang and Chen et al. (2017) evaluated the effectiveness of a FC in an ophthalmology clerkship in comparison to the lecture-based classroom. The students report feeling greater motivation to learn the subject matter, and that the FC approach improved their critical judgement and communication skills. Further, there was performance improvement in the FC knowledge compared to the historical traditional learning. Interestingly, there was no difference in performance for non-traumatic ocular content.

There is also work being done with the incorporation of the FC approach in a radiology clerkship rotation (Belfi et al, 2015), where improvement in knowledge was seen with the FC approach compared to traditional learning. Pursuit of the FC is also in development within a US based internal medicine residency program (Vincent, 2014).

Hew and Lo (2018) conducted a meta-analysis looking at the impact of student learning using the FC in all health professions. They reviewed almost 30 studies that included professions such as medicine, nursing, dentistry, pharmacy and occupational health, as well as others. These studies included 4 randomized controlled trials. The 28 studies provided data on 2295 subjects exposed to FC and 2420 subjects exposed to traditional classroom revealing that the FC had led to an overall favorable effect of a statistically significant improvement in student learner performance on their education. Interestingly, in a subanalysis they found the effect to be greater when the instructor used an in-class quiz at the start of the session to assess prior learning.

Not all medical knowledge can be obtained with a FC approach. Tang et al (2017) felt that classes considered to contain more abstract material were less suitable for a FC. We can then extrapolate this in the consideration of equally important non-clinical realms including professionalism, medical ethics and communication. These areas, for which physicians are expected to demonstrate competency, may be more difficult to learn with a FC strategy. But these areas are also not well evaluated with our traditional testing methods of “yes or no” or multiple-choice examination. As further discussed in Tang et al (2017), methods to accurately evaluate the impact of FC on abstract subjects are limited, thus, it seems that the absence of benefit is not due to the FC per say, but rather due to the absence of good evaluation methodology. There are also other clerkship learning objectives where a FC approach could not be used, including in the development of skills obtained from the ward, such as bedside manner (Williams, 2016).

Is a flipped classroom approach acceptable to medical students? Students’ perspectives have been evaluated through retrospective surveys. Students are reportedly highly satisfied with pre- class videos (Ramnanan & Pound, 2017) that support their preparation for a FC learning environment. Notably, students report that the FC stimulates their interest in the topic and improves their motivation and engagement in class. Medical students also value active learning in class, such as improvement in self-regulation, peer learning and help-seeking that the FC offers (Zheng & Zhang, 2020).

This is similar to pharmacy students as well. Khanova, Roth, Rodgers, and McLaughlin (2015) designed and implemented an entire FC curriculum. They found that the students preferred the FC compared with the traditional lecture-based curriculum. However, this was conditional upon effective delivery and alignment with objectives.

The landscape of medical training is changing. The FC is a new approach that may offer improved medical training in both the preclinical and clinical years, and perhaps in residency. However, there is a need for robust randomized trials to determine the effectiveness of the FC for knowledge performance using quantitative measures. It is clear that medical students are keen on its application, citing their heightened satisfaction, and improvement in communication and critical judgement skills. There are limitations, challenges and opportunities available, requiring faculty to approach this thoughtfully in its continued development.

SWOT Analysis

Our analysis of the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats of the Flipped Classroom reveal the following:

| Strengths | ||

| Learner Centred | Flexible Environment | Allows the learner to control and access their space, assessments and timelines |

| Flexible Learning Styles | Can respond to a variety of learning modes and abilities; self-paced and personalized | |

| Feedback | Continual formative feedback, adjusted as needed | |

| Intentional Content | Content is meaningful and relevant, resulting in more positive student attitudes (greater enjoyment, less boredom, higher perceived task value) | |

| Collaborative | Student-Student Interaction | Increased opportunity for students to work together and help each other learn |

| Weaknesses | |

| Reliance on Professional Educator | Requires educators fluent in: continual feedback, reflective practice, open to criticism, willingness to change/experiment/adjust, flexibility |

| Educator Workload | Increased preparation time and effort, burden of student-teacher interaction (availability) |

| Effect on Learning | Inconsistent results (Chen et al) re: student knowledge, skills and behavioural change; pre-class learning may be geared to audio/visual learning styles |

| Learner-centred Responsibility | Trust-based system; success depends on student motivation, compliance and active participation |

| Digital Divide | Learners require access to technology – reliance on technology results in inequity between learners; difficulty with online distractions |

| Screen Time vs. Live | Increased screen time vs live interaction? |

| Testing Challenges | May be more difficult to examine material, depending on subject |

| Resistance to Change | Learners and educators need to buy in to the program |

| Slower Learning | Learner-centred classroom may lead to a slower learning process, with less material covered in limited class time |

| Opportunities | |

| Creativity | Change & growth for learner and educator |

| Learner Responsibility | Successful learners will develop self-discipline |

| Higher-level Learning | Could maximize use of class time for higher-level thinking and learning |

| Learner-Teacher Interaction | Teaching time available to spend on personalized instruction during class time |

| Peer Collaboration / Networking | Learners develop networks to support each other both in and outside the classroom |

| Community | Online learning exposure available to larger community beyond the classroom – parents, colleagues |

| Best Academic Areas for Use | |

| Undergraduate Health Professions Education | Pre-clinical areas, basic medical sciences |

| Clerkship | Growing use of FC across Health Professions |

| Postgraduate Medical Education | Developing use of FC across Health Professions |

| Threats | |

| Learner Responsibility | Self-discipline required |

| System Resistance | Educators, learners and administrators must buy-in to the FC process |

| Lack of Resources: Technological | Lack of access to necessary online/ technological resources (i.e. digital divide; inequity between socioeconomic classes of students) |

| Lack of Resources: Educator | Staffing (i.e. covid – lacking staff trained in teaching online); Budgeting for more preparation time (creating lesson materials / online videos) |

| Technology Myth | Does not replace having a good teacher; the Flipped Classroom is a technique, does not guarantee good results in all learners |

| Suitability of Curriculum | Knowledge in learners may vary depending on topic (i.e. abstract areas, skills development) and can be challenging to evaluate |

Tales From the Field

The Flipped Classroom method has been utilized at the College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, as the following examples illustrate:

1st Year Anatomy:

Dr. Greg Malin is an Assistant Professor with the College of Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan, and currently the Academic Director UGME Program. He teaches Anatomy to first year students and became increasingly dissatisfied with the traditional method of lecturing. He found that the students were quite good at learning basic facts but struggled with application. He decided to use the Flipped Classroom method to change this. Initially, he pre- recorded his lectures and had students do group work. He found having the classroom time be quite structured was key in getting the students to focus, otherwise they spent too much time socializing and not really learning.

Dr. Malin provides some key points for implementation of the Flipped Classroom (October 2020):

-

- Pick one session and do it well; if you try to do too much, you won’t do any of it well, and you’ll feel it failed;

- For pre-recorded videos break them down into smaller videos (5-10 minutes), this will keep it focused, and keep the students’ attention (note: you don’t have to use videos);

- Focus pre-session materials on the basic key facts and the in-class activities, on application (or higher level) of those facts;

- Be respectful of students’ time. Keep pre-session materials as brief as possible, and try to set the in-person activities so students can complete them in the class time available, or a close as possible;

- Provide clear instructions for students so they know what to expect leading into the session;

- Provide the pre-session materials to the students at least a week in advance;

- Have fun with it – the key is to do whatever is comfortable for you.

Dr. Malin polled the students and found they enjoyed the sessions more and felt that they were able to grasp and apply the material better, being able to connect Anatomy to clinical scenarios. An additional benefit was that he found that as he moved around the room, it gave him an opportunity to talk with students one on one or in small groups, allowing him to get to know them better and develop a relationship.

Medical Student feedback:

Ben Abelseth is a final year medical student in the College of Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan. As a learner, he provided a few pointers on his experience with the Flipped Classroom. (October 2020) He felt that it was easier to retain the information because the students were actively involved with the delivery of the materials. He suggested that most important in having a successful Flipped Classroom were clear objectives given ahead of the session that were reasonable to complete in the given time. If the expectation is reading beforehand, recommended sources should be given.

Clinical Skills:

One of the authors of this chapter also has experience in this form of instruction. Dr. Helen Chang teaches in the Year 2 Clinical Skills courses, where students participate in various Flipped Classroom-type learning experiences. Lectures can be accessed online, and then students take part in small group sessions involving Standardized Patients. This format has been used for teaching Advanced Communication skills, as well as for practicing and refining physical examination and history-taking techniques. The experience is generally a positive one for learners, although it quickly becomes apparent if a student has not prepared sufficiently for the small group session. Overall, students are highly motivated to participate, and the realism of the clinical session allows the experience to stick with them into their further training.

Conclusion

As an innovative educational strategy, Flipped Learning may offer alternative strategies to traditional lectures. Students have found it to be valuable and enjoyable, and there is evidence that it may aid in learning. While there may be a learning curve, we encourage instructors to give the Flipped Classroom a try!

References

Abelseth, B. (2020, October 12) Personal Interview.

Acedo, M. January 28, 2019. 10 Pros and Cons of a Flipped Classroom. TeachThought. Accessed Oct. 7, 2020. https://www.teachthought.com/learning/10-pros-cons-flipped-classroom/

Belfi, L.M., Bartolotta, R.J., et al (2015). “Flipping” the introductory clerkship in radiology: impact on medical student performance and perceptions. Academy of Radiology: 22: 794.

Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2012). Flip your classroom: Reach every student in every class every day. Eugene, Or: International Society for Technology in Education. pp 20-33

Chen, F., Lui, A. M., & Martinelli, S. M. (2017). A systematic review of the effectiveness of flipped classrooms in medical education. Medical Education, 51(6), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13272

Chen, Y., Wang, Y., Kinshuk, Chen, N. (2014) Is FLIP enough? Or should we use the FLIPPED model instead? Computers & Education 79 (2014) 16-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.07.004

Flipped learning: the advantages and disadvantages. Accessed Oct. 7, 2020. https://www.easy-lms.com/knowledge-center/about-flipped-classroom/flipped-learning- advantages-and-disadvantages/item10610

Hew, K.F., & Lo, C.K. (2018) Flipped Classroom Improves Student Learning in Health Professions Education: a meta-analysis.BMC Medical Education, 18(38). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1144-z

Khanova, J., Roth, M.T., Rodgers, J.E., & McLaughlin, J.E. (2015) Student experiences across multiple flipped courses in a single curriculum. Medical Education, 49: 1038-1048; https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12807

Krueger, J. June 23, 2020. Five Reasons Against the Flipped Classroom. Accessed Oct. 7, 2020. https://stratostar.com/five-reasons-against-the-flipped-classroom/

Liebert, C.A., Lin, D.T. et al. (2016). Effectiveness of the surgery core clerkship flipped classroom: a prospective cohort trial. American Journal of surgery. 211: 451.

Lewis, C., Chen, D., Relan, A., (2018) Implementation of a flipped classroom approach to promote active learning in the third-year surgery clerkship. American Journal of Surgery. 215(2), 298-303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.08.050

Malin, G. (2020, October 11) Personal Interview. .

Office of Medical Education Research and Development at Michigan State University (October, 2020) What, Why, and How to Implement a Flipped Classroom Model. Retrieved from https://omerad.msu.edu/teaching/teaching-strategies/27-teaching/162-what-why-and-how-to- implement-a-flipped-classroom-model

Prober, C.G., & Khan, S. (2013). Medical education reimagined: A call to action. Academic Medicine. 88(10): 1407

Quigley, A. (2013). Flipping the Classroom: What is a Flipped Classroom? LinkedIn Learning. https://www.linkedin.com/learning/flipping-the-classroom/what-is-a-flipped- classroom?u=2059300. Accessed October, 2020.

Ramnanan, C.J., & Pound, L.D. (2017). Advances in medical education and practice: student perspectives of the flipped classroom. Advances in Medical Education and Practice. 8:63.

Sams, A., Bergmann, J., Daniels, K,. Bennett, B., Marcshall, H. W., Arfstrom, K.M. (2014) Flipped Learning Network (FLN). The Four Pillars of F-L-I-PTM.

Saskatchewan Education. Instructional Approaches: A Framework for Professional Practice. (October, 2020)Teaching as Decision Making. Retrieved from https://www.webpages.uidaho.edu/cte492/Modules/M3/Methods-Strategies.htm

sushislifeblog. April 6, 2016. Disadvantages and limitations of the Flipped Classroom Model. Accessed Oct. 7, 2020. https://flippedclassroomed690.wordpress.com/2016/04/06/disadvantages- and-limitations-of-the-flipped-classroom-model/

Tang, F., Chen, C. et al. (2017). Comparison between flipped classroom and lecture-based classroom in ophthalmology clerkship. Medical Education Online.77 https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2017.1395679.

The Flipped Classroom. May 14, 2020. Digital Pedagogy – A Guide for Librarians, Faculty and Students. Accessed Oct 7, 2020. https://guides.library.utoronto.ca/c.php?g=448614&p=3552449

Vincent, D.S. (2014). Out of the wilderness: flippin the classroom to advance scholarship on an internal medicine residency program. Hawaii Journal of Medicine Public Health. 73(11 Supplement 2): 2.

Whillier, S., & Lystad, R.P. (2015). No differences in grades or level of satisfaction of satisfaction in a flipped classroom for neuroanatomy. Journal of Chiropractic Education. 29(2):127.

Williams, D.E. (2016). The future of medical education: Flipping the classroom and education technology. Ochsner Journal. 16:14.

Zheng, B., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Self-regulated learning: the effect on medical student learning outcomes in a flipped classroom environment. BMC Medical Education. 20:100.