Specific Fluid Types

See Table 5.3

Hemorrhagic Effusions

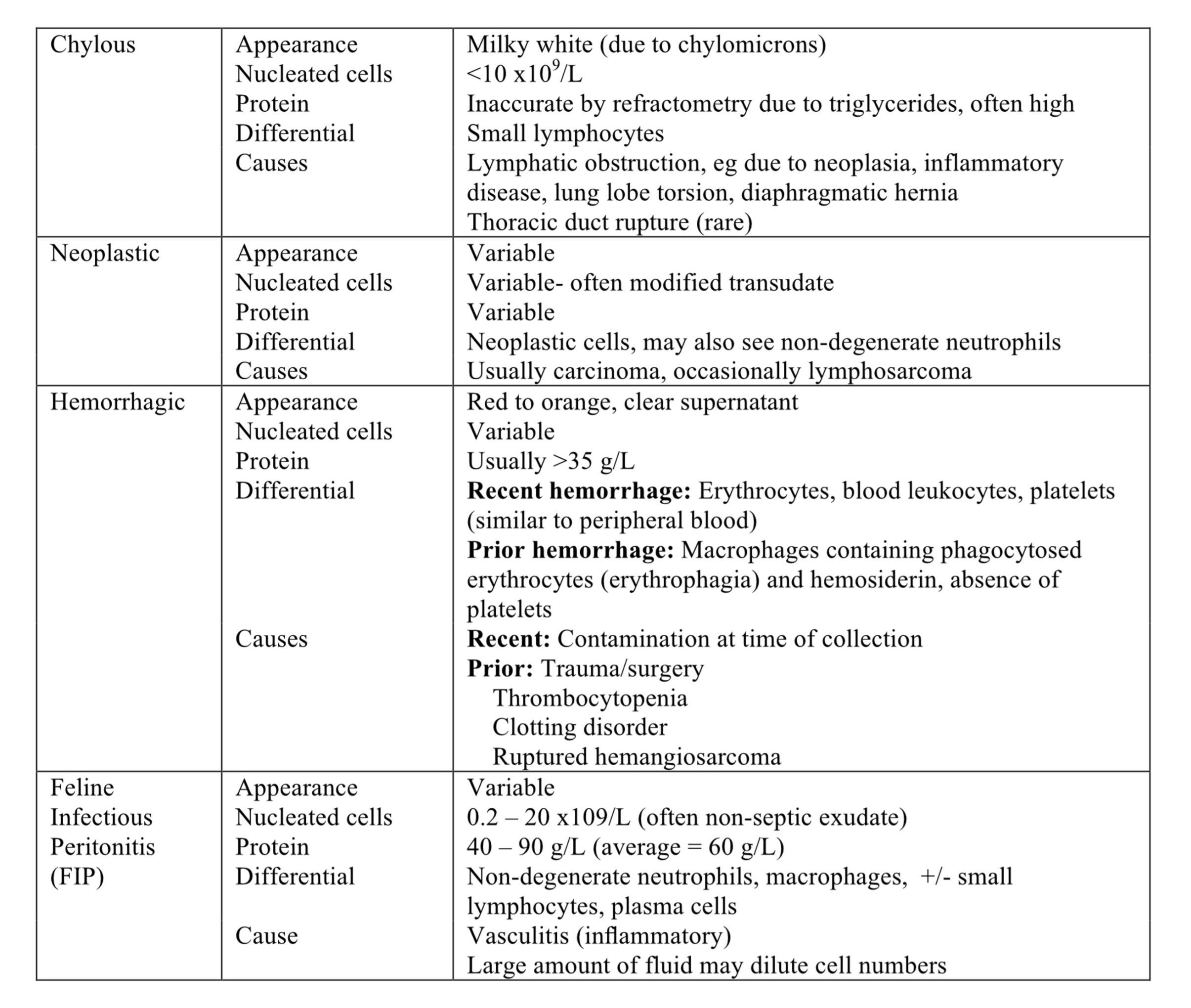

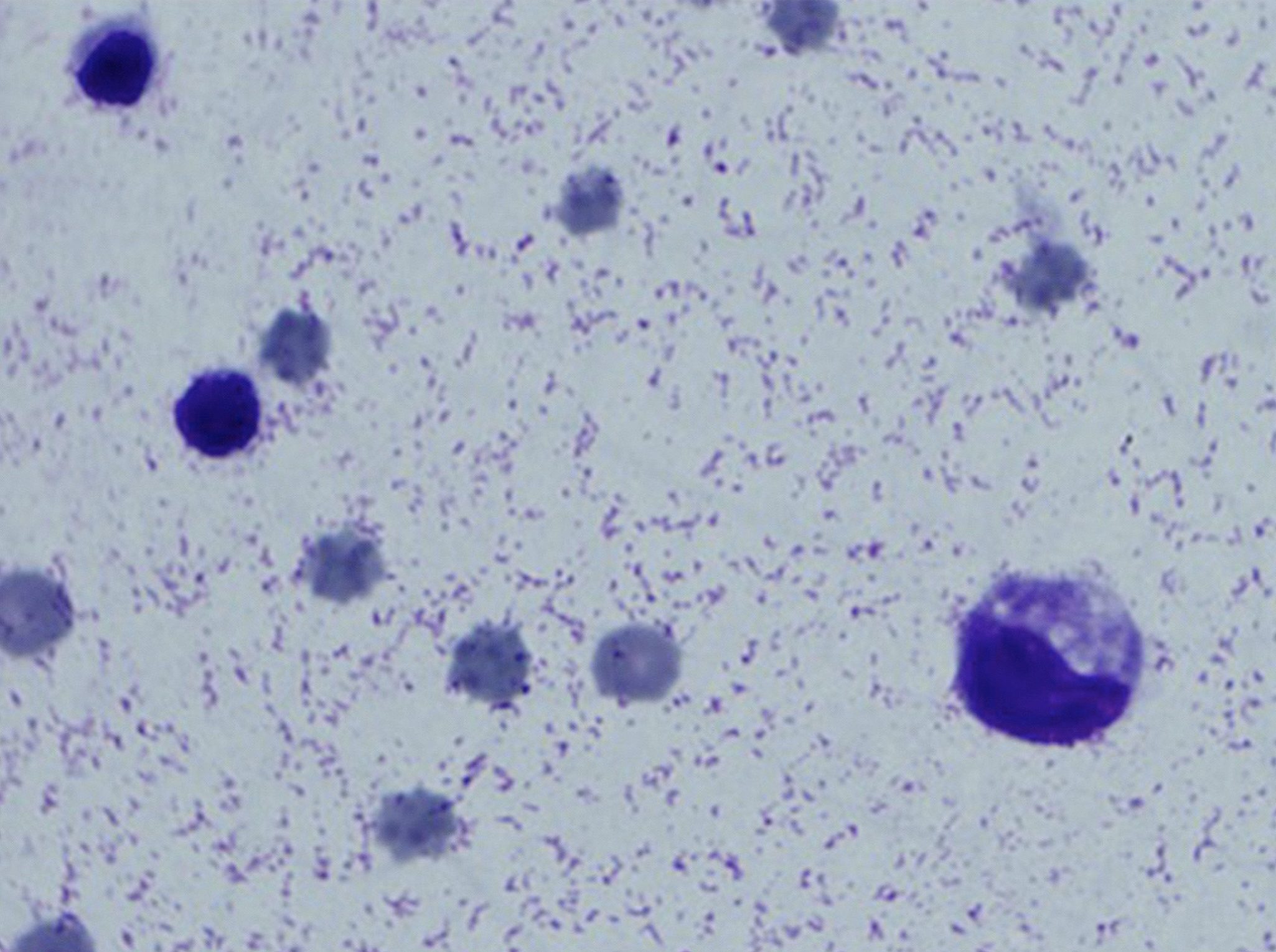

Hemorrhagic effusions have protein concentration and cell counts similar to peripheral blood. There are several causes of hemorrhagic effusions: trauma, surgery, coagulopathy, rupture of a damaged vessel, and rupture of a fragile, blood-filled tissue (such as ruptured hemangioma or hemangiosarcoma of the spleen). Contamination of the sample with peripheral blood can occur at the time of collection and should be differentiated from a true hemorrhagic effusion. Platelets lyse and disappear from hemorrhagic effusions within a few hours. Also, monocytes (and later, macrophages) begin to phagocytose erythrocytes within a few hours (Fig. 5.34). After several more hours, erythrocyte degradation results in the presence of hemosiderin within macrophages. In very long-standing hemorrhagic effusions, macrophages are the predominant cell type and abundant hemosiderin and possibly hematoidin crystals (bright yellow, rhomboid shaped crystals) will be noted.

Chylous Effusion

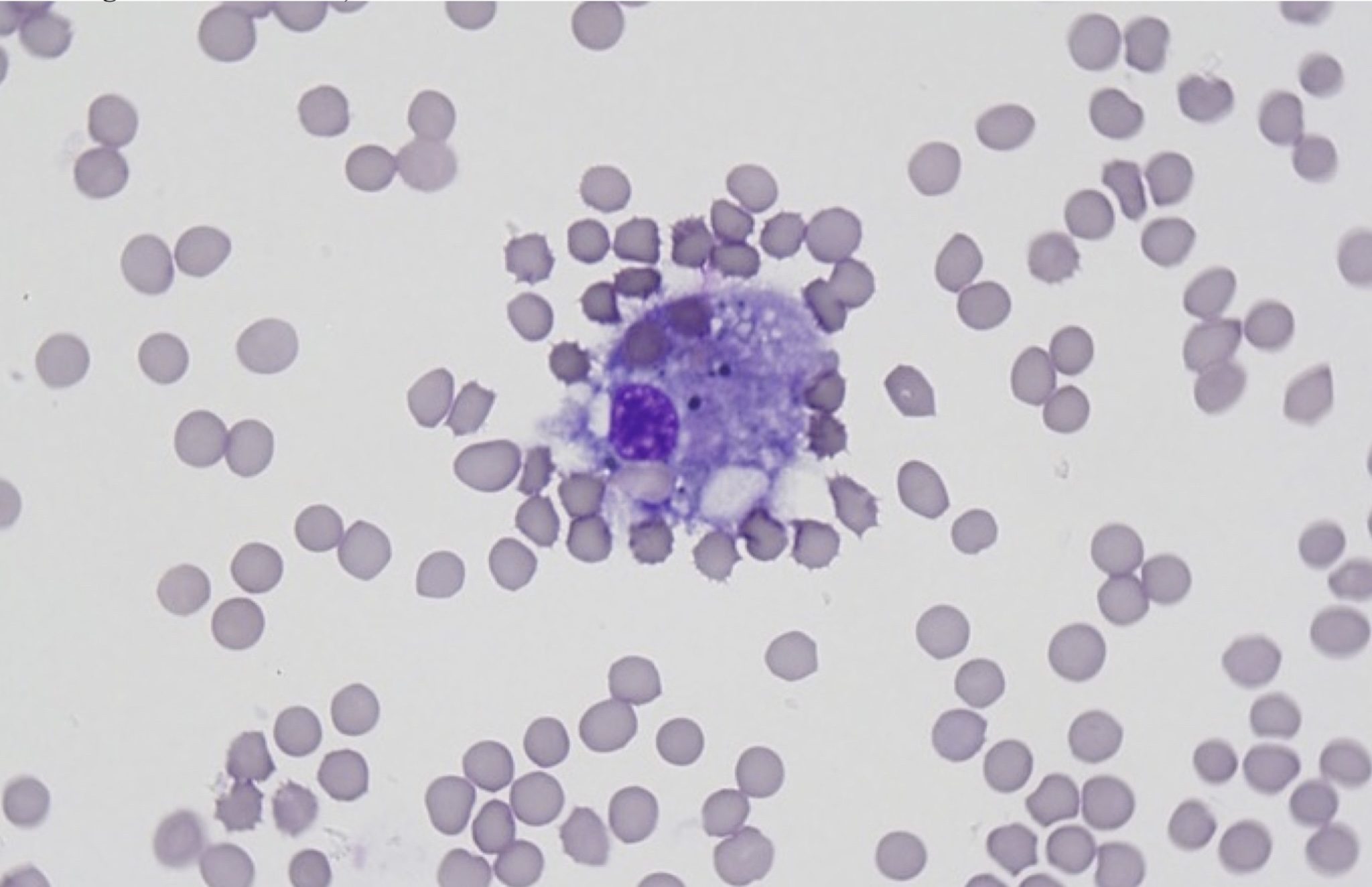

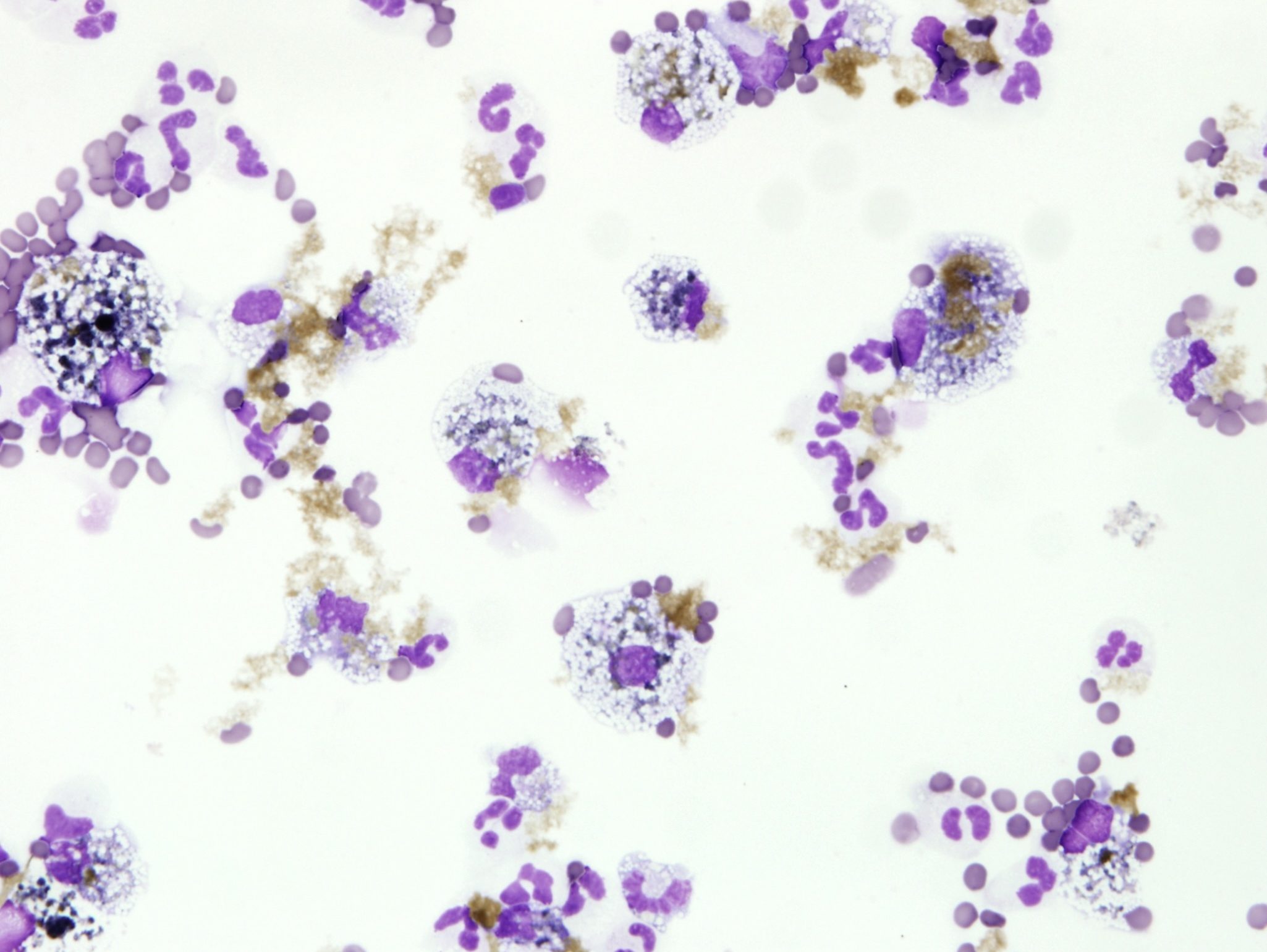

Chylous effusions can be seen in both the abdominal and thoracic cavities. The fluid is milky white or cloudy pink (Fig. 5.35). The protein concentration is inaccurately high on refractometry due to the presence of lipid (triglyceride) droplets. The triglyceride concentration in the fluid is usually at least three times the serum triglyceride concentration. The nucleated cell count for chyle is usually <10 x 109/L, and small lymphocytes predominate in acute chylous effusions (Fig. 5.36). Macrophages are also present and often contain small lipid droplets. With longstanding leakage of chyle or with chyle drainage (e.g. through repeated thoracocentesis or placement of a chest tube), numbers of nondegenerate neutrophils often increase and these and macrophages may be the predominating cells, with only low numbers of small lymphocytes (resembling a nonseptic exudate).

Any condition leading to lymphatic hypertension or impaired lymphatic drainage can result in chyle leakage. Examples are neoplastic or inflammatory lesions in the region of the lymphatic duct(s), cardiac disease (especially cardiomyopathy in cats), dirofilariasis, chronic coughing and vomiting, lung lobe torsion (can be either a cause or a result of chylothorax), and diaphragmatic hernia. There is also breed-related chylothorax in Afghan Hound dogs. The cause is sometimes not identified despite thorough investigation, in which case the chylous effusion is termed idiopathic. Rupture of a lymphatic duct is one of the least common causes of chylous effusion. Bicavitary chylous effusions (chyle in the thorax and abdomen) are most often due to neoplasia.

Neoplastic Effusion

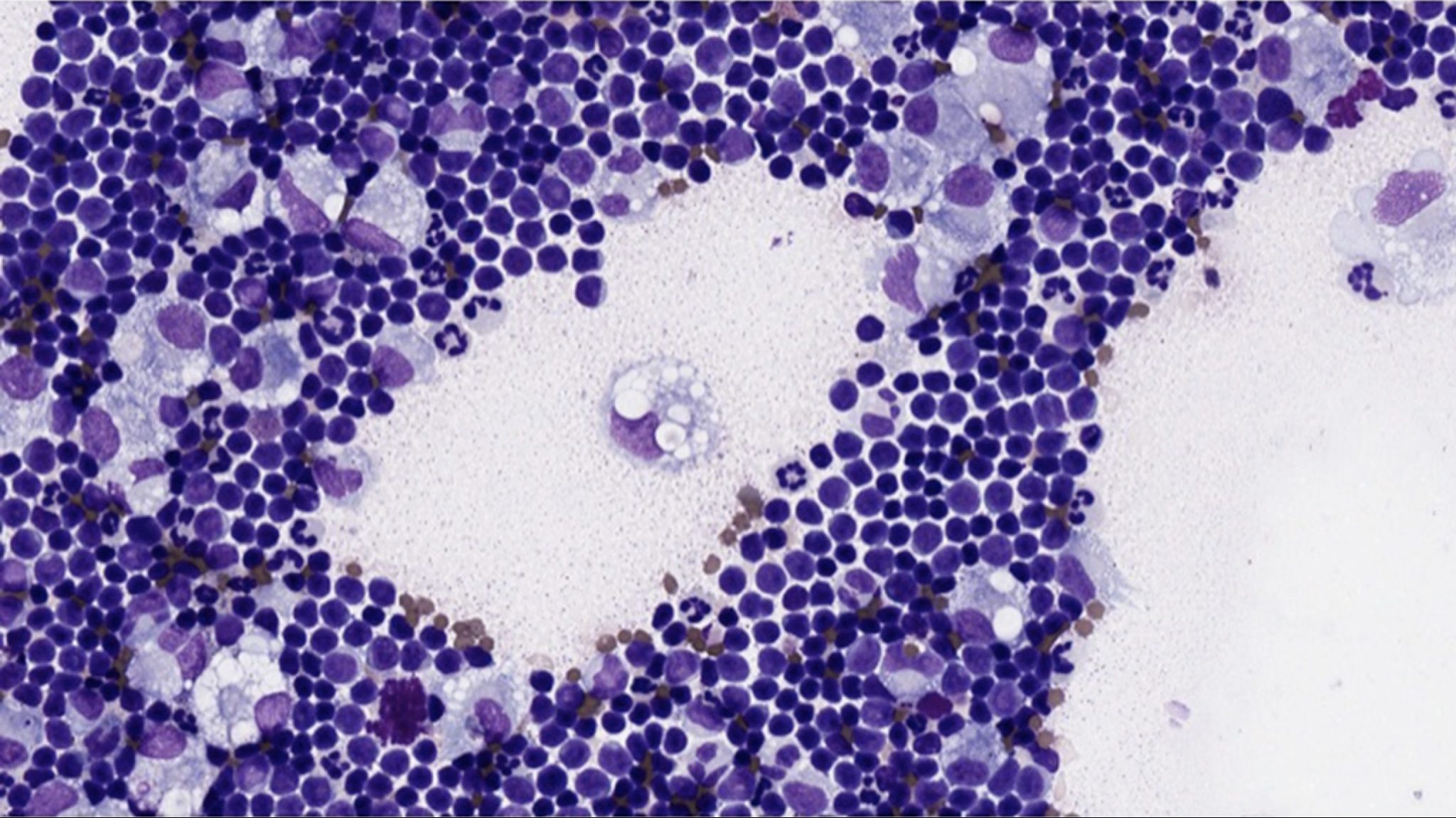

Neoplastic masses that exfoliate into the pleural or peritoneal space usually produce a modified transudate or exudate which may be cloudy to serosanguineous. Exfoliating lymphosarcoma can be identified by the predominance of large lymphocytes, often with prominent, large nucleoli, and abundant mitotic figures. The neoplastic cells may be very fragile and rupture easily. A few small lymphocytes and macrophages may also be present. Carcinomas and sarcomas also sometimes exfoliate into body cavities. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, a tumor of aged cats and dogs, usually exfoliates into the abdominal cavity such that typical malignant epithelial cells are identified on cytology (Fig. 5.37). Splenic hemangiosarcoma is a common mesenchymal neoplasm of older dogs that often produces a hemorrhagic effusion that may also contain tumor cells.

Pericardial Effusion

Pericardial effusions can occur for the same reasons as thoracic or peritoneal effusions. In the dog, many pericardial effusions are hemorrhagic and the cause may be neoplastic (e.g. due to atrial hemangiosarcoma) or idiopathic, with other causes such as trauma or hemostatic defects reported less frequently. Cytology of canine pericardial fluid often reveals numerous reactive mesothelial cells and it can be difficult to differentiate these from a neoplastic population. Further testing is often needed to determine the cause of the pericardial effusion.

Feline Infectious Peritonitis

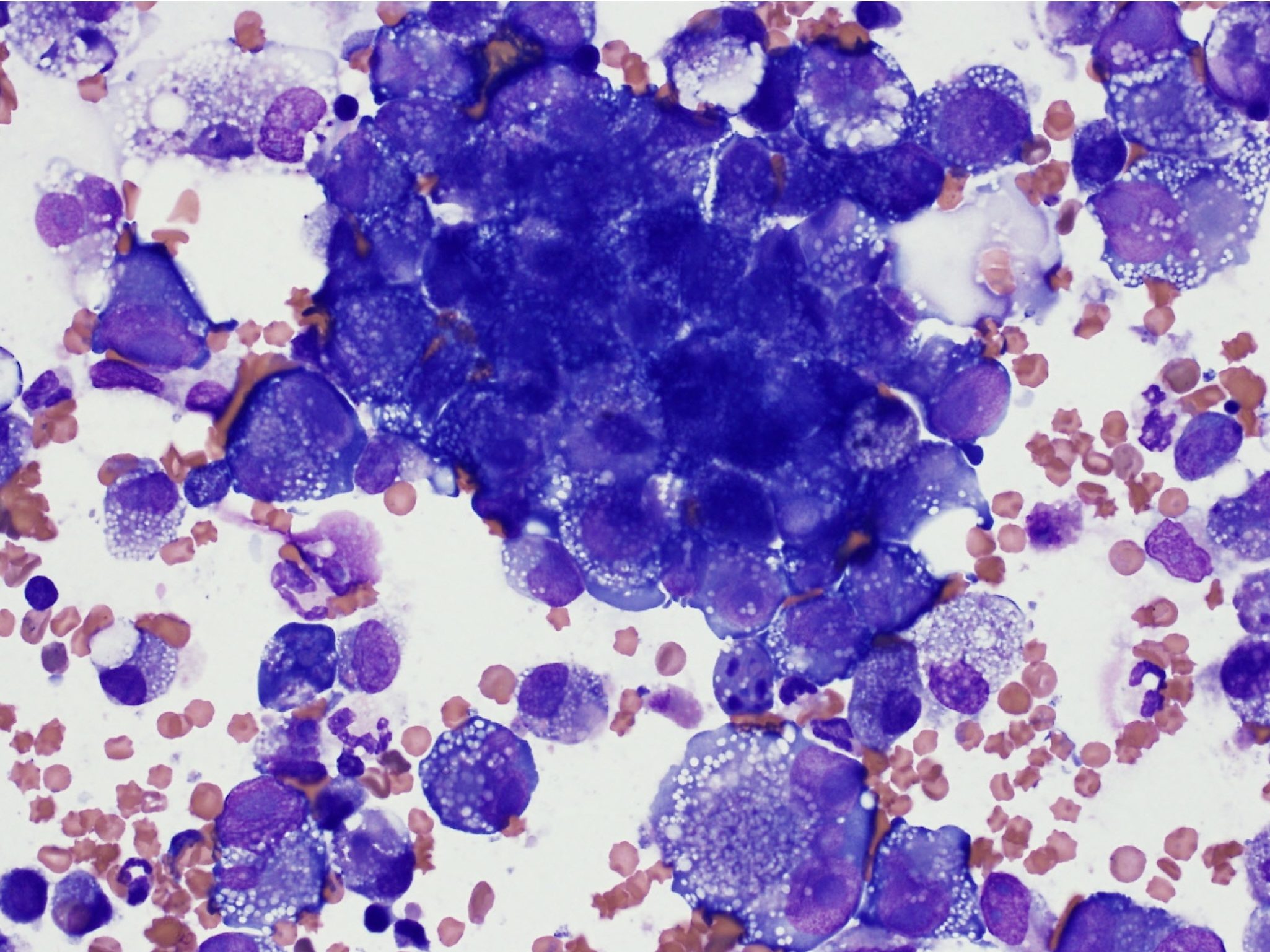

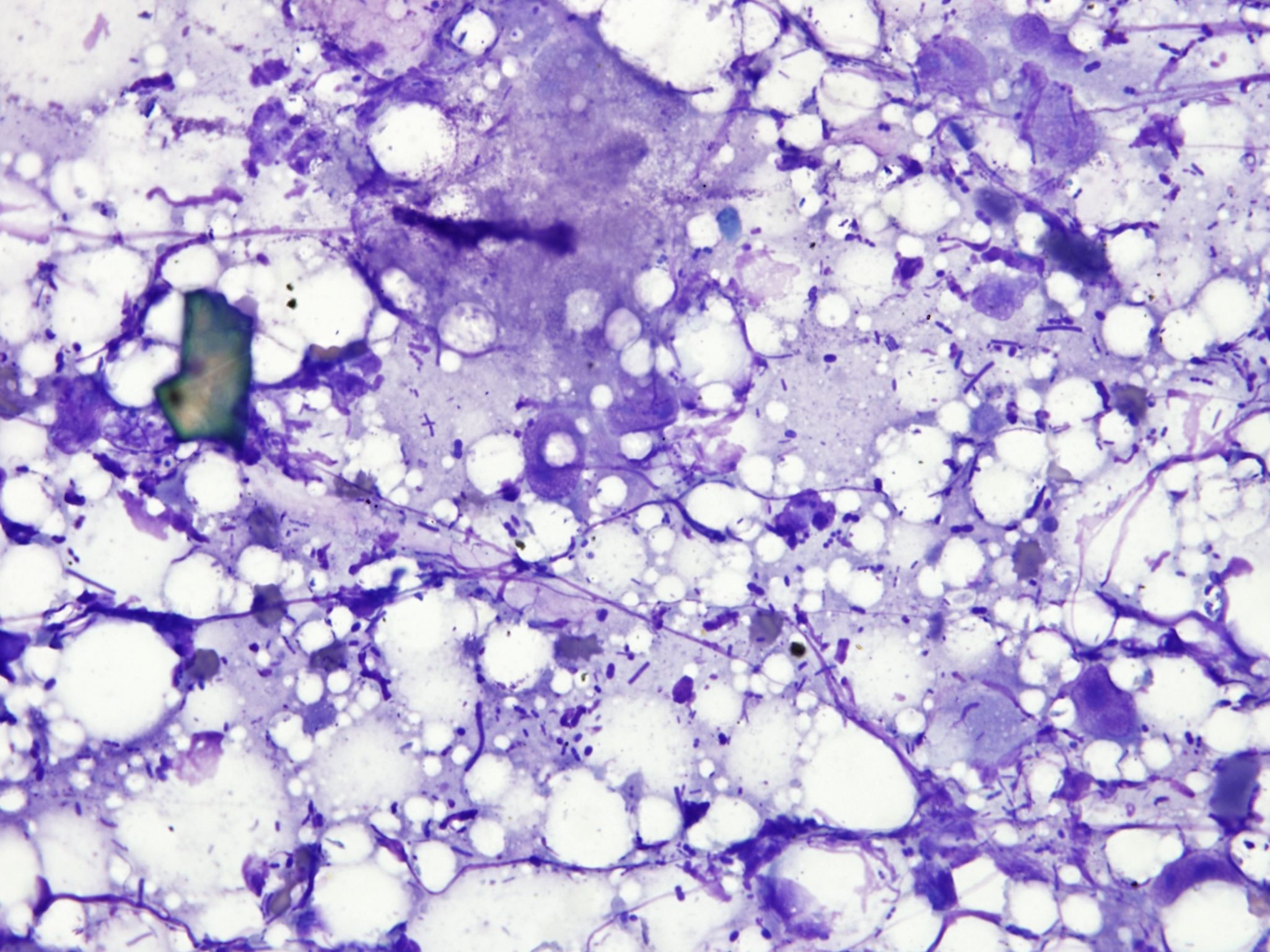

Feline infectious peritonitis virus infection produces a nonseptic effusion that is very viscous and may contain flecks of fibrin. The protein content can be very high (40-90 g/L) and most of the protein is immunoglobulin. The background of a direct smear is highly stippled due to the protein content and this causes cells to shrink, sometimes making them difficult to identify (Fig. 5.38; see also Case 1). Careful evaluation of the feathered edge of the smear, where the background is thinner, aids in identifying the cell types. The proteinaceous stippling should not be confused with bacteria. Electrophoresis of the serum or fluid protein reveals a polyclonal increase in gamma globulins. Nucleated cells are more variable, at counts of 0.2-20 x 109/L, and consist of a combination of nondegenerate neutrophils, mesothelial cells, macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.

Bile Peritonitis

Bile leakage typically causes a nonseptic exudate, unless there is pre-existing infection in the biliary tree. Sterile bile causes irritation, resulting in a chemical peritonitis, and macrophages are drawn into the cavity to phagocytose bile pigment. Nondegenerate neutrophils, free bile pigment, and bilirubin crystals may also be seen (Fig. 5.39). Grossly, the fluid can be brown to green. Sometimes, blue-grey mucinous material may be noted cytologically (white bile). This is thought to be bile-free material produced when there is extrahepatic biliary obstruction. Animals are typically icteric and serum activities of cholestatic hepatic enzymes are increased. A peritoneal fluid bilirubin concentration that is >2 times the serum bilirubin is diagnostic of bile peritonitis.

Bovine Peritonitis

The inability to obtain peritoneal fluid from cattle does not preclude the existence of peritonitis or other peritoneal pathology because the large forestomach in ruminants can hinder fluid retrieval. Nucleated cell numbers may fall within the reference interval in bovine peritonitis due to the low neutrophil reserve in bovine bone marrow. Although nucleated cell counts up to 30 x 109/L can occur with chronic, low grade peritonitis in cattle, counts are usually <10 x 109/L in more acute situations. The cytologic findings are very important in interpreting if inflammation or sepsis is present. These should also be related to the history, physical findings, and other laboratory findings, especially the CBC. Normal bovine peritoneal fluid may contain variable numbers of eosinophils (as high as 70%), which are rapidly replaced by neutrophils, macrophages, or both when inflammation is present. Degenerate change in neutrophils should trigger a diligent hunt for bacteria.

Equine Colic

Abdominocentesis is very useful in decision-making on colic cases in horses. With gut infarction and sepsis, small organisms such as Strep. fecalis are seen first, followed by E. coli. When gut rupture is a sequela to devitalization, Clostridial organisms and plant material will be seen. Degenerate neutrophils should also be present and peripheral blood findings will reflect acute, severe inflammation. If the gut is tapped inadvertently rather than the peritoneal space, there will be a mixture of bacteria and plant material, but no inflammatory cells (Fig. 5.40). Peracute gut rupture that is not secondary to intestinal tract pathology can be very difficult to differentiate from a gut tap, because there may be little time for an inflammatory reaction to develop before death.

Uroabdomen

Uroabdomen that is not related to underlying urinary tract inflammation/infection or urolithiasis generally results in a low protein, cell poor fluid (transudate). If there are abundant urine crystals entering the abdominal cavity, an inflammatory response comprising mainly macrophages would be expected. Pre-existing urinary tract infection at the time of the rupture will result in septic peritonitis. However, normal urine causes little peritoneal reaction. Depending on the nature of the rupture (size and vascularity), the fluid may be sanguineous or clear. Urine has a high osmolarity relative to serum so fluid will be drawn into the abdominal cavity from the vasculature and interstitium. Biochemical abnormalities in serum relative to abdominal fluid facilitate making the diagnosis (see Chapter 6: Fluids, Electrolytes, and Acid-Base Balance and Chapter 7: Renal System).

Fluid accumulation comprising peripheral blood; resembles peripheral blood but lacks platelets if more than a few hours old. Erythrophagia by macrophages is also present.

Defect in secondary hemostasis (coagulation).

An anucleate (in mammalian species) cytoplasmic fragment arising from a megakaryocyte; vital for primary hemostasis.

Mononuclear phagocytic leukocyte that develops into macrophages in tissue.

Major storage form of iron within tissues (insoluble).

Fluid accumulation due to the leakage of chyle; contains primarily small lymphocytes and triglycerides

Method of measuring the protein content of a fluid that relies on refraction of light, which is proportional to the quantity of solids in solution.

Type of lipid used as an energy source.

Of unknown cause.

The end product of coagulation, produced by the conversion of fibrinogen.

Break-down product of hemoglobin.

Process of obtaining abdominal fluid for cytologic evaluation.

Leakage of urine into the abdomen due to trauma, inflammation/infection, or neoplasia involving the urinary tract.

Concentration of osmotically active particles in solution expressed in osmoles of solute per liter of solution (mmol/L).