Chapter 8: Writing in University: It’s All About the Process!

8.2 Stage One: Prewriting Activities

Your work on an essay begins the moment you receive the essay prompt or assignment. Get started on your paper early.

First, it’s critical to understand what the assignment is asking by reading it closely, listening to what the professor says about it, and then choosing a topic.

After choosing a topic, you likely will need to narrow it, think about your audience, and begin a list of search terms for your research. You can start to research it, talk to a librarian, make an outline, do some close reading, and draft a working thesis statement.

As you know, before you’ve even started writing your essay, there are many details to attend to, some more time-consuming than others.

This chapter explains several strategies and activities for the first chunk of time you spend on your paper: the prewriting stage.

Step 1: Reading your assignment

Interpreting Assignment Prompts

If you rush through reading an assignment prompt right into research and writing, you can make mistakes with big consequences. While you ultimately may write a great essay, if it doesn’t respond to the assignment prompt and follow directions, it can receive a failing mark.

Professor’s assignment directions can vary quite a bit. While one professor will write a five-page list of instructions, another will simply ask you to hand in ten pages on a topic of your choosing. It can never hurt to ask your professor some well-thought-out questions to clarify the assignment directions, but do a good job of reading the assignment carefully before asking questions. Don’t ask him or her a question that is answered in the assignment directions.

Tips for Understanding Assignments

Review the document “Following the Instructions.” It has a handy decoder for assignment verbs. What does it mean when your professor asks you to analyze a controversy? Discuss a case? Another helpful resource on understanding assignments can be found here.

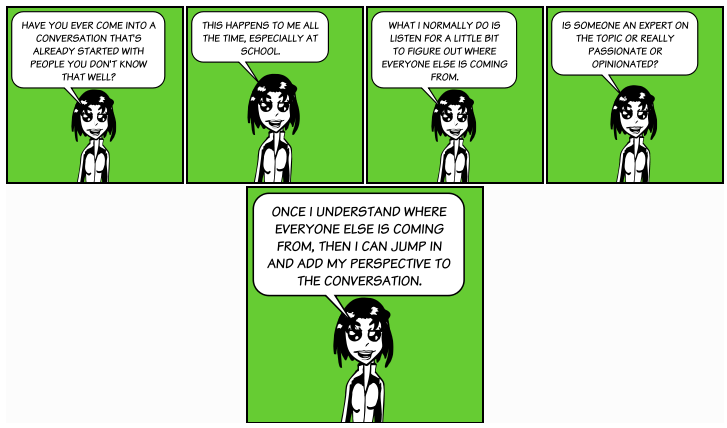

At this stage, you may be wondering how to enter the scholarly conversation.

http://www.clipinfolit.org/writing-tutorial/1-getting-started-with-your-research/2-research-as-a-scholarly-conversation/1-joining-the-scholarly-conversation

Step 2: Identifying a topic

Your first step toward getting started on a research paper is to identify a topic. Your professor may have given you a specific topic, but often in post-secondary study, as in this class, your professors will give you a general guide and you will need to narrow it down to a specific topic on your own. This is sometimes easier said than done, especially when the course material is unfamiliar to you.

To make it easier, try to find a topic that’s interesting to you so that you’re more motivated; was there a lecture topic that was fascinating to you? Have you found something in your readings that caught your eye? For example, are you interested in the research on handwritten notes versus notes taken on a computer? Do you think “first generation” students are more likely to drop out of University?

Your next step is to conduct background research on the topic that you’ve identified. This step is where you may find out that the topic you identified earlier is more complex than you’d thought, or you may want to go in a new direction based on learning new information. In fact, the topic you identify and develop usually will not be the topic you finish with.

Here are some tips for conducting background research:

- Get a general overview of a topic to see where it stands in the big picture. You can use your textbook, encyclopedias, general books on the topic, and even Wikipedia (see “Using Wikipedia for Academic Research”).

- Once you have a sense of the scope of your topic, and how that topic connects to other topics, you can determine ways to approach it. See the animated video “Mapping Your Research Ideas,” from UCLA Library.

Once you’ve done background research, you will need to determine an approach to the topic, and maybe even narrow it down. Angie Gerrard, University of Saskatchewan librarian, says, “Consider asking yourself the five W’s about your topic: who, what, when, why, where. For example, is there a specific population or group (who), time period (when) or geographical location (where) you would like to focus your research on?”[1].

In high school, your teachers may have given you a topic to write about for a research essay or paper, and you could include a lot of information about that topic from a few sources. In post-secondary writing, your professor will likely want you to narrow a broad topic to dig more deeply into the research to find information on that now-specific topic.

For example, imagine writing a high school essay on Queen Elizabeth I of England. You research and write about where she was from, her parents, England’s place in the world, what she was like as a leader, her relationships, what wars she was leader during, and her influence on the arts. Your teacher wants to know how much you know about Queen Elizabeth I.

However, for a university-level history essay, you may just be writing a ten-page paper on one of those list items, such as her leadership during times of war, or her connection to the theatre. Your professor doesn’t want to know how much you know about Queen Elizabeth I; he or she wants to see if you can research and analyze one aspect of her rule. Most university research topics focus on depth, not breadth, of knowledge and understanding.

Think of it this way: at higher levels of interest and knowledge about a subject, we are more interested in the details and specifics, not the broad picture. For example, if someone is passionate about hockey, he or she doesn’t want to talk about how many players are on a team, and how many teams are in the NHL; rather, he or she wants to talk about a specific player, or a specific game, or a specific set of player statistics.

Your professors are the same: they know that you can memorize information, or produce a paper comprised of basic information about Queen Elizabeth, or water security in the 21st century, but that’s not as interesting to them. A political studies professor might rather you wrote an analytical comparison of Canadian water security policy to Canadian water security policy twenty years ago, rather than a description of what Canadian water security policy is. A description of that policy is just as uninteresting to this professor as a monotonous description of the basic rules of hockey is to a person who loves hockey.

For more information and guidance, watch the animated video “Picking Your Topic IS Research” from Eastern Kentucky University Libaries.

Brainstorming keywords

You’ve done some research on your topic and considered an approach to it. Now really dig into your topic by brainstorming keywords to use as search terms. U of S Librarian Angie Gerrard advises,

Let’s say you are writing a psychology research paper and you have decided to investigate the potential gender differences in the use of social media sites by adolescence.

Your next step is to identify the main concepts in this research question; these terms are gender differences, social networking sites, and adolescence. These concepts will be the keywords and phrases you will use to search for information on your topic.

While you are undertaking some preliminary research, begin to note some of the other keywords or synonyms that have been used to describe your topic. Think of additional keywords or synonyms you could use to describe your topic to find further information; this is a great way to broaden or narrow your topic. For example, in the sample research question, if you were not finding enough information using the concept adolescence, you could also try searching teens or teenagers. Alternatively, if you found too much information on the concept social media sites, you may want to narrow-down your search to a specific site such as Facebook or Twitter. It is helpful to keep a list of various potential search terms for the main concepts of your research topic. This ensures you have plenty of search terms to assist in your search for information.

Additional Help:

- Watch the following video to help you get started with selecting and narrowing your topic:

“Picking your Topic Is Research” video: http://www.lib.ncsu.edu/tutorials/picking_topic/

- The University Library’s website’s “How Do I?” page provides detailed information on navigating the University Library. This site includes everything from finding articles, to printing, and booking group study rooms.

Step 3: Finding Information Sources

Conducting research can be overwhelming. A study that examined post-secondary students’ research habits showed that students used the words “angst, tired, dread, fear, anxious, annoyed, stressed, disgusted, intrigued, excited, confused, and overwhelmed” [2] to describe their emotions around research.

Finding information sources can be fun, though, too. A student once described to me why she liked so much: “it’s detective work!” Good researchers, like good detectives, do not have a preconceived idea about what the answers are going to be; they ask a lot of questions, observe closely, seek the truth, and look for details that others miss.

The University of Saskatchewan Library’s U-Search tool makes sources easy to find when you start a search. Watch the University of Saskatchewan Library’s 2-minute video, “How to Find a Few Good Articles.” For more help with developing a good list of search terms, view the short slide show “Generating Search Terms” (Cooperative Library Instruction Project).

Scholarly vs. Popular Sources

Scholarly books and journal articles differ from popular books and magazine articles in a number of ways. Scholarly sources introduce new ideas and knowledge taken from original research or experiments. Most scholarly articles undergo something called peer review, where other experts in the author’s field assess the articles to recommend rejection, revision, or acceptance for publication. They include citations, and usually are longer. Popular sources differ from scholarly sources: they are not peer reviewed, rarely include citations, usually are not written by experts, and tend to be shorter. Professors will not want to see popular sources such as Wikipedia or Sparknotes used as references in your essays.

Primary and Secondary Sources

When you start researching, you will encounter different sources of information. It’s good to know the difference between a primary source and a secondary source. Professors will sometimes request that you use one or the other, or a combination. A primary source is an original source, such as a letter, diary, poem, speech, novel, artifact, photograph, interview, newspaper articles from the time, email messages, and survey data. A secondary source interprets or analyzes primary sources. Examples of secondary sources include bibliographies, critiques, essays, journal articles, textbooks, magazine articles, and histories. Often, first year classes, such as English literature, will have you focusing solely on analysis of primary sources, with a little bit of dictionary work thrown in!

Reading and Evaluating Information Sources

Finding articles is one thing, but understanding them and assessing whether they are worthy for a post-secondary academic essay is another.

Not only will your professors want a variety of sources in your papers, but also they will want you to use peer-reviewed, scholarly, up-to-date sources. Obviously, your sources should be related to your topic, and at the appropriate level for your assignment. Even if your sources meet these criteria, you still need to assess the authors’ objectivity, coverage, argument, authoritativeness, and accuracy.

When it comes time to assess your sources for your essay assignments, it’s worth the time to answer the “Critical Questions for Evaluating Websites and Print Sources.” If you prefer to watch a video, NCSU’s Evaluating Sources for Credibility is a clear and helpful introduction.

You may be searching for that one perfect article, but chances are that one perfect article does not exist. Rather, you will need to find a variety of sources that contribute to your research, and then present this synthesized evidence in your paper. View the NCSU Libraries video “One Perfect Source?”

View CLIP’s short, helpful slide show on knowing the difference between popular or scholarly sources.

Step 4 Composing a Strong Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is the central argument, in a sentence or two, placed near the beginning of your essay. Most professors would expect to see it at the end of your introductory paragraph. It should be concise, clear, and specific.

When faced with writing their first paper, many students think that because the thesis statement is emphasized as being the most important element of their essay, it had to say something BIG. Unfortunately, that meant that many first thesis statements are much too broad and vague, sounding more like announcements of a topic rather than arguments.

To get started with writing a thesis, try to come to a tentative main point. Answer the question, “What is the main point of this paper?” Think back to your research question. Your working thesis statement will be revised and tweaked as you write and discover new complexities. See Table 8.1 “Example Process: Narrowing Your Thesis Statement” for a walk-through of the process of coming up with a strong, specific thesis statement. Remember: your thesis should be something that someone can disagree or agree with; it’s not just an observation or statement of fact.

Table 8.1: Example Process: Narrowing Your Thesis Statement

|

Example Process: Narrowing Your Thesis Statement Your professor asks you to write a 10-page essay on the subject of homeschooling. You have a lot of flexibility in where to go with it. You know that you won’t be able to cover everything there is to do with homeschooling, so it’s safe to assume that you’ll narrow this topic. After some preliminary reading about homeschooling, you narrow your topic to write about elementary-aged schoolchildren in Canada. The research question you decide to answer is “will these children benefit more from homeschooling than from public schooling?” Once you start researching the population of Canadian elementary-aged schoolchildren, you realize that such a diverse group is hard to say any one thing about. You narrow your topic further by concentrating on a group on which you find a lot of research has been done: children with ADHD. Your working thesis might be “ADHD elementary schoolchildren would benefit from homeschooling more than from public schooling.” This is a start: you are stating a position, and you’ve narrowed your topic. While your opinion may even be based on your gut at this point, you may go on to do reading and writing that changes your mind. To further improve this working thesis, you might ask questions. Interrogate! Here are the sorts of questions you might ask of your working thesis “ADHD elementary schoolchildren would benefit from homeschooling more than from public schooling”: · Really? All ADHD children? What about gender differences? What about class differences? What about children with other challenges in addition to ADHD, such as a learning disability or a physical disability? Should I narrow this further to concentrate on gender or class? · What kind of homeschooling? There are many kinds of homeschooling. · What if the home is unstable or the parents can’t afford to homeschool? · All public schooling? Why am I focusing on public schooling as a contrast? Some of these questions are hard to answer, and may require further research. Let’s say that you did some research to begin to answer some questions, including some basic definitions of and types of homeschooling, some basic information on ADHD children in middle school and the challenges they face. You wouldn’t do too much reading yet – you could get lost in it. You would be reasonably ready to start to answer, for yourself, some of those questions. After trying to find answers to your own questions, let’s say that you came to this more precise, focused thesis statement, an improvement from the still-too-broad working thesis: Middle school children with ADHD, with stable homes and financially capable parents, would benefit from the classical, Socratic method of homeschooling (Wise and Wise Bauer, 1999). The classical method focuses on a child’s cognitive development and three phases of learning and thinking, and that, in combination with a more physical, temporal, and environmental freedom, would be fertile ground for an ADHD child to learn. This is much more specific, and will give your paper a focus, which will allow you to dig more deeply. The good thing about a specific thesis statement is that it is more reasonable and believable; if you limit your claims, you don’t have to do cartwheels to prove them. |

For further assistance on crafting a strong thesis statement, please view additional resources here:

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/545/01/

and here:

Step 5: Outlining your paper

Outlining is an important step before starting to draft. An outline is a general plan for the order of topics in an essay. An outline also shows the relative importance of the topics. Finally, an outline is informed by a specific, narrowed-down topic and main argument or thesis statement. A working thesis statement, or preliminary draft of your main point and argument should inform the scope of your outline.

Make sure you’re flexible about your outline. Being too “married” to it can make you blind to problems with it; you may find that the act of writing a draft can complicate and change how you think the paper should be organized.

Read the Purdue Online Writing Lab’s “Four Main Components for Effective Outlines.” Here:

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/544/01/

Putting some energy into creating a good outline will make your drafting process much more smooth and efficient.

And here:

https://sass.uottawa.ca/sites/sass.uottawa.ca/files/awhc-planning-the-paper-making-an-outline.pdf

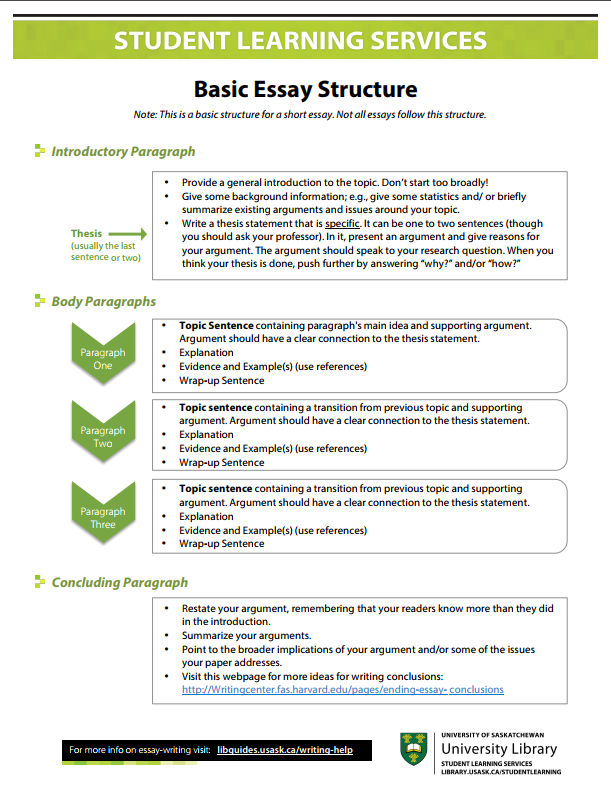

While there are many ways to write an essay, figure 8.4 provides an explanatory template for a basic, five-paragraph argumentative essay.