Chapter One: Making Sense of Public Schooling

1.4 The Purposes of Schools

Why have formal education at all, and why is school attendance compulsory? We tend to take the purposes of schooling as being relatively self-evident, but they are actually quite problematic. Begley (2010, pp. 33-35) drawing on the work of Christopher Hodgkinson, identifies three broad purposes for public schooling which he refers to as: the aesthetic – the formation of character and individual self-fulfilment; the economic – preparation for an adult work life; and, the ideological – socialization to the norms and conduct of society. These purposes are similar to historian Ken Osborne’s (2008) discussion of education, training, and citizenship as three competing expectations or goals for public schooling in Canada. While arguing for a “balanced presence” of each goal, Begley suggests that the emphasis and balance of these goals is always fluid, dynamic and contextual. Osborne, while noting that “public schooling in Canada was designed more as a tool for social policy than as an instrument of universal education” (p. 27) argues for the primacy of the educative purposes such that “school subjects are not things to be covered or memorized, but vehicles by which students might come to see themselves as heirs to a legacy of human striving that connects past, present, and future” (p. 37).

Coming at the question of purpose from a slightly different perspective, Barrow (1981) identifies six functions of schools —critical thinking, socialization, child care, vocational preparation, physical instruction, social-role selection, education of the emotions, and development of creativity. Many schools have adopted 21st Century learning goals with the aim to develop competence in the ability to make sense of information in order to use it critically and creatively in a frequently changing global world. To that end, the 21st Century goals of schooling include such competencies as collaboration and teamwork, creativity and inquiry, social responsibility, healthy living, global and cultural understanding, technological literacy, innovation, and critical thinking and problem-solving (Boyer & Crippen, 2014). There are also those who suggest that public schools need to also consider the spiritual aspects of students’ beings, whether that is religiously, culturally, or individually defined (Shields et al., 2005). This is exemplified in many Indigenous education frameworks whereby it is advocated that the goals of schooling include a holistic balance in the development of mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual wellness (Battiste, 2010; McManes, 2020)

The Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC) have endorsed what they consider to be pan-Canadian global competencies, which are quite similar to what has been advocated in 21st Century learning goals: critical thinking and problem-solving; innovation, creativity and entrepreneurship; learning to learn/self-awareness and self-direction; collaboration; communication, and global citizenship and sustainability. There has been agreement at CMEC that these competencies are embedded in many curricula, programs, and education initiatives across Canada.

It is not surprising, therefore, that these competencies can be found within the long-term and short-term plans of individual ministries, that in turn aligns with much of the planning of school districts. These plans can be found on ministry of education websites as they are seen as a means of holding provincial governments accountable for education in each province. Strategic planning has been significantly influenced by neoliberal ideology and notions of accountability that have become embedded in the language of plans. These plans typically include a focus on defining a vision (often implies the intended purpose), sets of priorities (similar to goal statements), target-setting, strategies for achieving the targets, measurements that can demonstrate achievement of goals, and timelines for completion. To that end, there is a sense of accountability built into the very design of plans, usually relying on quantitative measures for what constitutes achievement. Whether or not those measures tell the full story about student learning is often in debate, particularly from groups who suggest that measures tend to be normatively biased and cannot account for factors outside the school environment that affect learning and/or achievement.

The design of provincial and/or district plans typically look quite polished, but difficulties exist in how to enact them in unique local schools. There are several important questions to ask about any statement of educational goals:

- Are the goals mutually compatible?

- Are the goals achievable?

- Do the goals have a commonly shared meaning?

- Do the goals affect what schools do on a day-to-day basis?

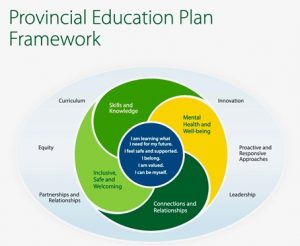

Before discussing these questions more fully, consider the planning framework for Saskatchewan that can be found in Figure 1.4.1 Goals are articulated in the centre of the framework which are described more fully in the complete plan.

Figure 1.4.1

Provincial Education Plan Framework

Compatibility

There is no guarantee that all the goals on any list can be achieved at the same time. It may be that achieving one purpose will necessarily be at the expense of another. There is only so much time, energy, and resources. If one of our goals is to make students physically fit, the time spent on fitness cannot also be spent on reading, yet goal statements rarely suggest any order of priority among their multiple objectives.

Most school system goals are very ambitious, and it is reasonably clear that accomplishing all goals all at a high level would take more time and energy than is currently available. Thus, a school system is always faced with the problem of having to decide which goals should get how much emphasis. For instance, does it place its energy into improving mathematics, expanding multicultural awareness, improving students’ commitment to healthy living, or emphasizing critical thinking? Is it possible to accomplish them all?

More fundamentally, purposes and goals may be logically inconsistent with one another, such that pursuing goal x means, by definition, not pursuing goal y. For example, one common goal of schools is to teach students to think critically and to make their own decisions, while another common goal is to teach students to appreciate some of the basic values of our society, such as patriotism or respect for others. But what if a student, after thinking about it, decides that s/he does not want to be patriotic or to respect others? Are educators prepared to say that, because students have formed independent opinions, they are free to disregard social conventions? Probably not. One of the basic tensions in schooling is between our desire to help individuals learn to think for themselves and our desire to have those individuals develop basic attitudes and values of respect and responsibility so as not to fall into social chaos. It is not possible to maximize both of these goals at the same time; the same logic applies to numerous other mutually conflicting school goals. It is important to know how decisions are made as to which goals will be prioritized, and to question whose interests those decisions serve.

Achievability

It is one thing to write down a goal, and quite another to be able to accomplish it. It is doubtful that schools can achieve all the goals set for them, even if there is agreement on what those goals are. Knowledge about how people learn and about how to teach them is, and always will be, limited. There are many things schools would like to do, but we don’t always know how to support learning for each and every student. As an example, consider the very basic skill of learning to read. Some children learn to read almost effortlessly, while others learn only with considerable difficulty and still others do not learn to read well at all. Learning differences exist not because teachers or students aren’t trying, but because, although we know much about the reading process, we can never fully know which strategies will optimize the learning of particular children, and we are therefore often only partially successful in teaching them.

If teaching students to read presents difficulties, it is even harder to teach values, such as an appreciation of the worth of all individuals or love of learning. It is equally important that we consider carefully which (or whose) values are being taught, and if, unintentionally or not, those values perpetuate inequities for students. Of course, just because educators aren’t sure how to accomplish something does not mean they should stop trying. It is important to set our sights high and to expect a great deal from ourselves. But setting many goals we do not know how to achieve is likely to create considerable frustration.

Shared Meaning

A statement of goals is an attempt to generate agreement among many people as to what schools should do. In education, it is common for school members to come together to create a “shared vision,” which also requires agreement on aims and purposes. But, as we have already noted, there may be quite a bit of disagreement among and between parents, students, teachers, and others as to what the schools should do. Some students, for example, especially in secondary schools, place high value on preparing for jobs. Some teachers may place more emphasis on goals such as developing positive personal habits and attributes while others might emphasize post-secondary educational opportunities. Some parents want a great deal of emphasis placed on reading and writing skills, while others want more emphasis on the arts or sciences. Some parents want their children to be exposed to many different ideas, while others want schools to reinforce the values of the home.

Such different priorities have significant implications for the way schools and teaching are organized. To place more emphasis on preparing for jobs, for example, schools could increase the amount of vocational and technological education, or provide work-experience opportunities for students. On the other hand, placing more emphasis on academic skills might involve cutting back in the above areas and allocating more time and resources to literacy and numeracy initiatives. A desire to offer a liberal arts education may necessitate investing in arts programs while reducing budgets in other areas to accommodate. Different goals lead to different kinds of activities and the need to shift resources accordingly.

One way that schools try to cope with the differences in people’s desired goals is to smooth them over with language. Thus, a statement of goals can be worded in such a way as to generate agreement, even if people would not agree on what the statements mean in practice. As long as the discussion stays at the level of words, the disagreement can be hidden. Often this approach works reasonably well in allowing people to move ahead with their work instead of spending endless time debating purposes, but it can also lead to the perpetuation of unfair and ineffective practices with increased ambiguity on how to actually organize people, time and resources.

Impact on Practice

It is one thing to espouse a goal and quite another to be able to put that goal into practice. The gap between goals and practices exists because it is difficult to align our behaviour with our ideals. It is much easier to align one’s self with an ideal than it is to put it into practice when it competes with other ideals, some of which appear to contradict each other. Given that schools are in the “people business,” and that at the heart of the educational enterprise are people’s dreams for their children or the youth of the nation, it is not surprising that discrepancies develop between thought and action in school organizations.

An important aspect of this discrepancy is the acknowledgment that while school systems may talk about success for all students, the historical record is that schools have not met this goal. Throughout Canada’s history, some students, whether those who live in poverty, recent immigrants, Indigenous people, people of colour, people in isolated communities or others, have often had less access to high quality schooling and less opportunity to fulfil their potential.

These issues are increasingly evident in Canadian education and are a concern for schools and districts (Glaze et al., 2012). The excerpts from the Toronto District School Board policy statement on equity (see Box 1.4.1) offer an example of how a school district recognizes the significance of systemic biases within Canadian society and Canadian schools and tries to ensure equity of opportunity and equity of access to its educational programs, services, and resources.

Box 1.4.1

Toronto District School Board Policy Statement on Equity

Each and every student is capable of success. Our focus is ensuring that all students can succeed by having access – the same access – to opportunities, learning, resources and tools; with the goal of improving the outcomes of the most marginalized students. That’s equity.

To do this, the TDSB has made a bold commitment to equity, human rights, anti-racism and anti-oppression. This sets the foundation to support those who have been traditionally and currently underserved, and will raise the bar for all students.

Enhancing Equity at TDSB

- Professional Learning

- Transforming Student Learning

- Creating a Culture of Student and Staff Well-Being

- Providing Equity of Access to Learning Opportunities for All Students

- Allocating Human and Financial Resources Strategically to Support Student Needs

- Building Strong Relationships and Partnerships within School Communities to Support Student Learning and Well-Being

Source. Toronto District School Board. Equity. Available at https://www.tdsb.on.ca/About-Us/Equity

The fact that goals are hard to define and difficult to achieve should not be taken to mean that the effort to do so is fruitless. Important decisions about education are made every day by students, teachers, administrators, school trustees, and others. These decisions need to be based on some sense of direction and purpose, despite all the difficulties in doing so. The goals may evolve, and they may never be fully achieved, but they remain a beacon in our day-to-day efforts.