Chapter Nine: Teachers and the Teaching Profession

9.4 An Alternative View of Teaching as a Profession

For some authors (e.g., Coulter & Orme, 2000; Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012), the differences between the practice of occupations such as medicine and law and those of teaching (particularly public school teaching) suggest the inappropriateness of efforts to define and pursue teacher professionalism according to the standards established for other occupations. For example, professionals in some fields do not work well collegially whereas teachers need to do so. Many professions try to keep their specialized knowledge confidential from their clients, while teachers must work collaboratively with students and parents as well as colleagues. One could go on elaborating differences, but the point is that these differences do not necessarily constitute grounds for downplaying the professional status of public school teaching. What they do require is that we recast the concept of professionalism as it is applied to the nature of public schools and the organization of teaching.

One revised formulation can be found in Goodson and Hargreaves (1996). They review four alternative versions of teacher professionalism which they refer to as “flexible professionalism,” “practical professionalism,” “extended professionalism,” and “complex professionalism,” and propose a fifth version, “postmodern professionalism.” This fifth version they see as driven primarily, not by interests of self-serving status enhancement or of technical competence and personal, practical reflection, but by a moral and socio-political vision of teaching as serving the educative goals of caring communities and vigorous social democracies. For them teacher professionalism in the contemporary complex, postmodern age should mean:

- increased opportunity and responsibility to exercise discretionary judgment over the issues of teaching, curriculum and care that affect one’s students;

- opportunities and expectations to engage with the moral and social purposes and values of what teachers teach, along with major curriculum and assessment matters in which these purposes are embedded;

- commitment to working with colleagues in collaborative cultures of help and support as a way of using shared expertise to solve the ongoing problems of professional practice, rather than engaging in joint work as a motivational device to implement the external mandates of others;

- occupational heterogeneity rather than self-protective autonomy, where teachers work authoritatively yet openly and collaboratively with other partners in a wider community (especially parents and students themselves), who have a significant stake in the students’ learning;

- a commitment to active care not just anodyne service for students. Professionalism must in this sense acknowledge and embrace the emotional as well as the cognitive dimensions of teaching, and also recognize the skills and dispositions that are essential to committed and effective caring;

- a self-directed search and struggle for continuous learning related to one’s own expertise and standards of practice, rather than compliance with the enervating obligations of endless change demanded by others (often under the guise of continuous learning or improvement);

- the creation and recognition of high task complexity, with levels of status and reward appropriate to such complexity (Goodson & Hargreaves, 1996, pp. 20–21).

Hargreaves and Fullan have extended this articulation of teaching as a profession and teacher professionalism with their work on professional capital (Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012; Fullan et al., 2015; Hargreaves & Fullan, 2020). Professional capital, they suggest has three components: human capital – individual talent, related to teaching qualifications, experience, ability to teach; social capital – collaborative action among teachers centred on instruction and grounded in trust; and decisional capital – the development through introspection and collegiality of expertise and judgement. The nurturing of professional capital offers a powerful vision for the teaching profession and for high quality schools. They argue that,

When the vast majority of teachers came to exemplify the power of professional capacity, they become smart and talented, committed and collegial, thoughtful and wise. Their moral purpose is expressed in their relentless, expert-driven pursuit of serving their students and their communities, and in learning, always learning, how to do that better. (Hargraves & Fullan, 2012, p. 5)

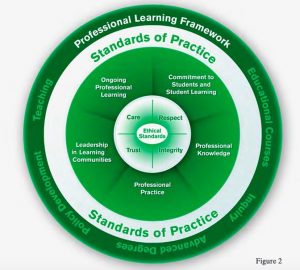

Box 9.4.1

An Ontario College of Teachers: A Collective Vision of Teacher Professionalism

The Ontario College of Teachers offers a model of teacher professionalism built on three pillars: Ethical Standards, Standards of Practice, and A Framework of Professional Learning.

Ethical Standards for the Teaching Profession

- Care, Respect, Trust, and Integrity.

Standards of Practice for the Teaching Profession

- Commitment to students and student learning; Professional knowledge; Professional practice; Leadership in learning communities; and Ongoing Professional learning.

A Professional Learning Framework for the Teaching Profession

- Educational courses; Inquiry: Advanced degrees; Policy development; and Teaching.

Source. Ontario College of Teachers (2016, June). Professional learning framework for the teaching profession. https://www.oct.ca/-/media/PDF/Professional%20Learning%20Framework/framework_e.pdf