Chapter Two: The Structure of Canadian Schooling

2.6 The Minister of Education and The Department of Education

In each province, the Department or Ministry of Education, headed by the minister of education, is the central educational authority. In some provinces postsecondary education and training is assigned to a separate minister and department, while in others both portfolios are included under one minister. The minister of education, an elected member of the provincial legislature, is appointed to the education portfolio by the premier; they are also a member of Cabinet. In the Canadian parliamentary system, the Cabinet responsible to the legislature is the key planning and directing agency of government. It approves all legislation brought forward by the government and formulates policy in education and all other areas of provincial jurisdiction. Although the drafting and passing of new laws often receives the greatest attention, it is only one of the ways in which government affects education. Since most provinces have only a few basic laws governing education, and these are not revised significantly very often, most government work in education lies outside the area of legislation. The distinctions among these various avenues of government activity are explained more fully in Chapters 3 and 4.

The role played by a minister of education at any particular period of time depends on the overall priorities of the premier and the government, and on the ability of the minister to influence these priorities. Nonetheless, because ultimate legal authority over education rests with provincial governments, ministers do play a critical role in determining how a province sets long-term educational policy and in influencing the level of funding provided to schools (see Chapter 5). They make, or approve, decisions about all sorts of educational issues, from new curricula to be introduced, to rules governing the certification of teachers, to the number of credits required for high-school graduation. The minister must defend before the public the government’s policies on education, even if they were opposed to the policy. And when parties to a local dispute at the school board or district level cannot come to an agreement, they will often call on the minister to intervene and settle the matter.

Being a government minister is an extremely demanding job. Leading a large and complex department is, in itself, a complicated task. But ministers must also participate in the work of the Cabinet as a whole, which means making decisions about all policy issues facing the province. Ministers are under constant pressure from various individuals and groups who wish to meet with them in order to influence what the government does. Ministers receive hundreds of such requests each year, just as they are asked to speak or appear at hundreds of public events. As politicians, ministers also have a responsibility to be in their constituency and available to the voters who elected them. Nor should we forget that ministers have personal lives and may reasonably want to spend time with family and friends.

Given all of this, no minister can possibly know all the details or activities under her or his authority. Most of the work of the department of education is done by civil servants within the broad guidelines set by the minister, or within agreements established by past practice. A great deal of this work is fairly routine or formalized. For example, the development of most new policies and procedures for schools normally proceeds through the work of committees, with the minister being involved, if at all, only at the end of the process in approving the final result. The issuing of certificates to new teachers (or teachers new to the province), the ongoing provision of money to school divisions, the approval of plans for new schools, the operation of distance education courses ‒ all of these activities are usually performed under the supervision of Department of Education staff. The direct involvement of ministers is usually reserved for items of great long-term importance or for those having to do with important policy directions, politically sensitive issues, or crises.

The department’s civil service is headed by the deputy minister, who is a civil servant appointed by the Cabinet. At one time, provincial deputy ministers were almost always career educators, many of whom had previously been teachers, principals, and school superintendents. In recent years, however, many provincial governments have brought deputy ministers into education from other areas of government. Unlike most other civil servants, deputy ministers serve at the pleasure of the Cabinet, which means that they can be dismissed by a government at any time. It is common in Canada when a new political party takes office after an election for the new government to replace some deputy ministers with people who are more sympathetic to its changed policy directions.

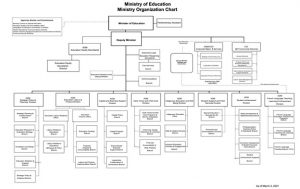

The deputy minister coordinates the work of the department in all its multiple functions. A typical department of education will have units dealing with areas such as planning, school finance, curriculum development and assessment, special education, language programs, and renovation or construction of school buildings. All of these tasks require full-time attention and some technical expertise; thus, departments of education today tend to be large organizations (although smaller than they were a decade ago) employing hundreds of people, many of whom are professional educators. The enormous range of issues dealt with in a department of education includes highly complex financial, legal, and technical questions, as well as issues typically thought of as educational, such as curriculum or school regulations.

The Department of Education is a mix of political and professional authority, embodying the tension between professional and lay control mentioned earlier in the chapter. The civil servants are generally guided by their professional training and background. Their views of the needs of education are influenced by their own background and training. They may be quite resistant to what they see as a partisan political direction taken by a government that wants public schooling to move in a certain way. The minister, on the other hand, is primarily oriented toward the political agenda of the government and to his or her own personal views and interests. The deputy minister and senior officials are caught in the middle; they are guided by professional values, but their job is to serve the duly elected minister and government. Under these circumstances, a sort of tug-of-war may occur in which ministers try to push their departments to move in particular directions, and civil servants try to convince ministers to see issues in the same ways that the civil service does. Usually, neither party feels entirely satisfied. Ministers feel that though they are elected to bring in certain policies, their will is often frustrated by unelected civil servants. Civil servants, on the other hand, feel that ministers do not always understand the subtleties of education, and may be guided by short-term political considerations at the expense of long-term educational needs. These tensions are part of the process of government and can contribute toward developing policies that are sensitive to both professional skills and public wants (Levin, 2005).

Figure 2.6.1

Ontario Ministry of Education Organizational Chart

Source. Ontario Ministry of Education Organizational Chart. Available at http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/general/edu_chart_eng.pdf