2 Where’s the Teacher? Defining the Role of Instructor Presence in Social Presence and Cognition in Online Education

Cathy L. Barnes

A persistent argument against the effectiveness of online learning is that it is inherently impersonal. In 2000, Garrison, Anderson & Archer introduced what has become the prevailing model (Community of Inquiry, or CoI) that provides a framework for understanding how community can exist within an online course. One of the major components of the CoI model, teaching, or instructor presence, has been studied extensively as a pivotal element for creating community and affecting learning outcomes. The intent of this literature review is to examine how instructor presence correlates to social presence and cognition in online learning. Findings among the studies include both validation and refutation of the role of instructor presence as an influencer in the development of online communities. As a result of this literature review, recommendations are made for further studies, and suggestions are offered for faculty development for online instructors.

Introduction

The notion of what a school looks like—a brick-and-mortar structure housing classrooms, textbooks, desks, teachers, and students—has changed substantially over the last two decades. To some, school appears the same, perhaps with the addition of computers and other technology. To an increasing number of students and teachers, in both K-12 and higher education, school consists of interactions with the computer itself in the virtual world of online education. There is little question that the ever-increasing number of online courses, programs, and schools is changing the educational landscape from K-12 to higher education. I believe online learning is flourishing in higher education because of the myriad of options and flexibility it offers to both traditional and adult learners, faculty, and the institutions themselves in fulfilling strategic and financial missions. For learners, online learning represents the ability to schedule around work or family, eliminate time-consuming travel, to work at their own pace, and even save on tuition (Chen, Gonyea, & Kuh, 2008). Allen & Seaman (2015) report that in 2013 there were over 7,000,000 students taking at least one online course. Although this number represents only modest growth (3.7%) over 2012, the number of institutions with distance offerings continues to grow. Over 70% of higher education administrators consider online education critical to their long-term strategies (Allen & Seaman, 2015). As a result, many traditional higher education faculty must face the necessity of moving content to a new, and sometimes challenging, teaching environment.

Online learning was not only the subject of many of my graduate courses, approximately 80% of them were delivered online. Most of my instructors demonstrated a strong presence during the course, which intensified my own social presence and desire to learn. However, I had experiences with several instructors who stopped communicating with the students, or did not provide feedback on significant assignments leading up to the final course project, or whose communication was limited to written announcements only.

During one course, the instructor seemed to have vanished by mid-semester. Coincidentally, in the same time period I participated in a webinar by Michelle Pacansky-Brock (2013), Humanizing Your Online Class. I was fascinated by Pacansky-Brock’s accounts of her own deliberate use of elements of teaching presence as a way to establish social presence in her photography courses. The webinar also led me to a micro-MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) entitled Human Element: An Essential Online Course Component (#HumanMOOC), hosted on the Canvas Network October/November 2013. I enrolled in the four-week course and was introduced to the Community of Inquiry (CoI) model designed by Garrison, Anderson, and Archer (2000), which described the concept of interplay between teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence. Within days of beginning #HumanMOOC, I was blogging, posting, and Tweeting® with fellow students, educators, and scholars around the globe, guided and encouraged by the moderators and fellow participants, experiencing teaching presence firsthand.

Despite frustration with the course I was taking for my academic program, I, and my fellow students, began to take charge and support one another as we approached the final weeks of the semester. While some of us continued to flourish in this newfound community, others appeared lost. The lack of feedback and direction from the instructor was frustrating with the final project deadline looming. I survived that course, but the lessons from the #HumanMOOC continue to captivate me, and have provided the impetus for this review, which explores how instructor presence correlates with social presence and cognition in the online learning setting.

Background

The social nature of education was espoused by John Dewey (1929), a revered theorist in U.S. education, who emphatically considered school as an integral form of community life. Dewey felt that teachers imposed too much control on students rather than being a part of the school community. He believed their mission was to guide students to handle social influencers and to foster a continual construction of knowledge. It is unlikely that Dewey could conceive of present day education occurring from such a distance that online learning allows, but his notion of the teacher’s role of guiding and observing a student’s interests is pertinent to this discussion.

Another perspective that supports the social nature of education comes from Vygotsky (1978), whose theory of the zone of proximal development proposes that optimal learning is achieved through both teacher’s guidance and peer interaction. The zone of proximal development is the distance between what an individual can learn on his/her own and the potential for learning with an instructor or a community of peers (Vygotsky, 1978). Further, Vygotsky states: “human learning presupposes a specific social nature” (1978, “A New Approach,” para. 13).

To answer criticism and perceived problems in higher education, Chickering and Gamson (1987) offered Seven Principles for Practice in Higher Education, which have come to be known as the dominant paradigm for developing standards of teaching and learning in higher education. The principles are regularly cited by contemporary researchers in relation to both traditional and online education. Like Dewey and Vygotsky before them, Chickering’s and Gamson’s (1987) principles include the significance of interaction between students and instructors, and students and their peers to promote learning. Their first principle states:

Frequent student-faculty contact in and out of classes is the most important factor in student motivation and involvement. Faculty concern helps students get through rough times and keep on working. Knowing a few faculty members well enhances students’ intellectual commitment and encourages them to think about their own values and future plans (Chickering & Gamson, 1987, p. 3).

The second principle promotes peer collaboration to expand understanding (1987). Combined, these two (of the seven) principles provide a basis for discussion of teaching, social, and cognitive presences. The remaining five principles: using active learning techniques, giving prompt feedback, emphasizing time on task, communicating high expectations, and responding to diverse talents and ways of learning are consistent with the characteristics of the CoI presences.

Michael Graham Moore (1989), editor of the American Journal of Distance Education since 1987, identifies three distinct types of interaction: learner-to-content, learner-to-instructor, and learner-to-learner. Learner-to-instructor interaction is described as encouraging interest and modeling, organizing information and assessing progress, maintaining individual contact with the learner, interacting frequently, and fostering the learner-to-learner interaction (Moore, 1989). It is Moore’s (1989) contention that these connections are keys to effective distance learning.

In 1993, Moore described what he called the first theory of distance education: transactional distance. He called it a pedagogical concept rather than just a geographic one, where “instructors and learners are separated by space and/or by time” (p. 22). More importantly, transactional distance is not a static measurement, but variable with dynamics based on the interaction or gap between any one instructor and any one student—including face-to-face environments—and includes both psychological and communications space where there is potential for misunderstandings. The space and time gap can be closed with deliberate elements of interaction by the instructor (1993).

These theories create a foundation for discussing studies about teaching, social, and cognitive presences in online learning.

Issues

My graduate studies in curriculum and instruction focused on the art and science of teaching. Deep knowledge of subject matter is only one piece of being a quality instructor. Keeping students engaged in that content, particularly online, involves understanding learning theories, student motivation, and how to use resources to deliver the content. According to Weimer (2012),

The typical college teacher has spent years in courses developing the knowledge skill set and virtually no time on the teaching set. This way of preparing professors assumes that the content is much more complex than the process when in fact, both are equally formidable (p. 17).

One aspect of online teaching is fostering the perception by students that the instructor is present in the course. “In a completely online instructional environment, instructor visibility is absolutely critical. Students need to know that the instructor is attending to them even though they do not meet in a face-to-face classroom” (Savery, 2005, p. 143). This visibility is teaching presence (Stavredes & Herder, 2014). Dzubinski (2014) defines teaching presence as “the ability to structure the class, create the social environment, give instruction, and assess student work… the basis for creating a community of inquiry in an online class where successful learning can occur” (p.1).

Community of Inquiry

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) model (Garrison et al., 2000) is the prevailing model in research involving teaching presence. At its core, CoI is built on constructivist principles rooted in educational theories of Dewey, Vygotsky, and others. Constructivism is a process of an individual’s construction of knowledge through his/her own experiences and develops in concert with interactions with others (Shea et al., 2005). Adult learners in particular respond well to constructivism because they learn best when they can relate to prior experience and circumstances relevant to their current needs (Yang, Yeh, & Wong, 2010).

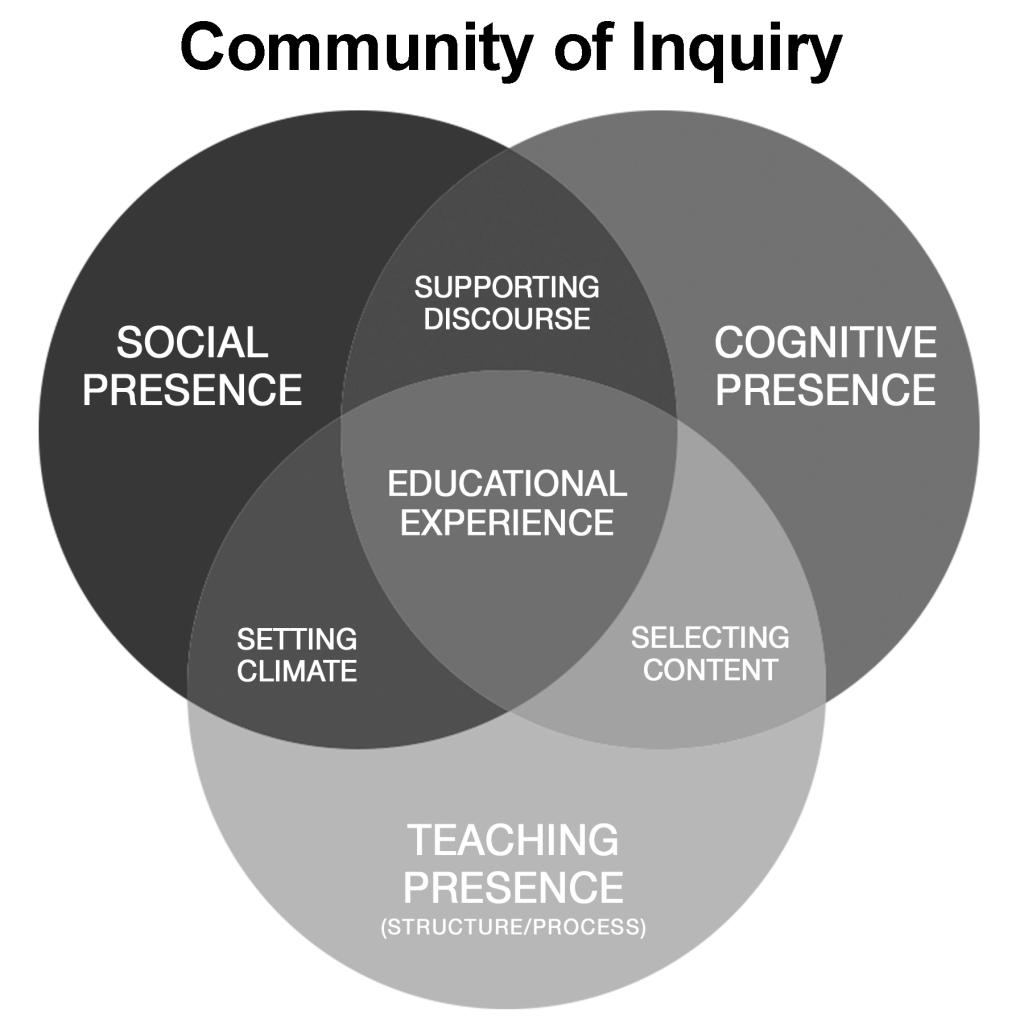

Garrison et al. (2000) developed the process model in an attempt to provide a framework for studies of the effectiveness and quality of online learning. Garrison et al. (2000) describe the Community of Inquiry as a “conceptual framework that identifies the elements that are crucial prerequisites for a successful higher education experience” (p. 87). Shea and Bidjerano elaborate that CoI “focuses on the development of an online learning community with an emphasis on the processes of instructional conversations that are likely to lead to epistemic engagement” (p. 544). Teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence are the essential components of the model (Garrison et al., 2000). Community is established by the convergence of the three presences (see Figure 1). Shea et al. (2003) propose that Chickering’s and Gamson’s (1987) seven principles can be found at the intersection of the presences in the CoI model.

Figure 1. Community of Inquiry (Garrison et al., 2000, 2001)

Instructor/Teaching Presence

A common misunderstanding about online learning is that it is “teacher-less” (Berge & Clark, 2009, p. 4). This misunderstanding likely stems from the false belief that all online classes are asynchronous, where students may never see the teacher face-to-face. Berge and Clark (2009) explain “good online teachers have regular interaction with their students” and “provide constructive feedback” (p. 4). Garrison and Cleveland-Innes (2008) demonstrate that the instructor is responsible for establishing and maintaining social presence in the course. Instructors need to learn techniques for creating teaching presence to stress design and facilitation along with projection of the instructor’s presence (Meyer, Bruwelheide & Poulin, 2009). Burkle and Cleveland-Innes (2013) encourage instructors to engage in the online environment itself as a participant, facilitator, mentor, and guardian. According to Berge and Clark (2009), quality standards for teaching online call for training, mentoring and monitoring of teachers, and include a rubric for evaluating them, but do not address teaching presence directly. One such rubric, the National Standards for Quality Online Teaching, was created by the International Association for K-12 Online Learning (iNACOL). The standards are directed at K-12 and a search of ‘online teaching standards’ returned several instances of state standards adapted from the iNACOL standards. No online teaching standard specific to higher education are available literature.

The primary perspective of teaching presence comes from Garrison et al. (2000) in their seminal article on CoI. They describe two primary functions of teaching presence: design and facilitation. Design includes the structure, content, and organization of the course while facilitation is setting the climate for learning through communication prompts, feedback, and guidance (Garrison et al., 2000). In the second article, Garrison et al. (2001) add the component of direct instruction. Garrison et al. (2000) suggest that the teaching role could be shared by the instructor and the students (although primary responsibility would belong to the instructor).

Key organizations that report on online education quality also include facets of instructor presence in their studies. In the Sloan Consortium (now known as the Online Learning Consortium, or OLC) Report to the Nation: Five Pillars of Quality Online Education, student-faculty interaction is associated with three of the five pillars: Pillar I – Learning Effectiveness; Pillar II – Student Satisfaction; and Pillar III – Faculty Satisfaction (Lorenzo & Moore, 2002). Noel-Levitz publishes its National Online Learners Priorities Report annually. The most recent report, 2014-2015, identifies at least two aspects of teaching presence, responsiveness, and timeliness, as deficient (Noel-Levitz, 2014). Quality Matters (2014), a benchmarking tool for online course design, includes characteristics related to teaching presence in its rubric standards, including etiquette expectations (or netiquette); self-introduction by the instructor and learners; learning activities that provide opportunities for interaction; and clear statement of response time, feedback, and learner interaction. Clearly, instructor presence is considered a vital element of quality online teaching by those who create standards for online courses.

Teaching online requires additional skills as the role of instructor and classroom manager is expanded into more of a facilitator of communication (Clarke & Bartholomew, 2013; Garrison et al., 2000, 2001; Shea, Li, Swan & Pickett, 2005). Within that role, Shea et al. (2005) found that directed facilitation of discourse likely made students feel higher levels of learning community. Directed facilitation includes whether students feel the instructor is drawing in participants, creating an accepting climate for learning, keeping students on track, diagnosing misperceptions, and finding consensus in areas of disagreement. Effective design and organization also contribute to a sense of community through communication of time parameters, due dates and deadlines along with clear course goals, course topics, and instructions for participation in the course.

Irwin & Berge (2006) point out that teacher “planning and intervention has a significant impact on socialization” (p. 6). Teachers who recognize these opportunities and learn how to foster them will better understand the need to establish their own presence in their courses. Oblinger (2014) stresses that, “students have varying needs. Students differ based on educational aspiration, preparation, age, motivation, self-confidence, sense of belonging and financial support” (p.18). Instructor presence is especially critical for those who are first time online learners as they need guidance and direction (Burkle & Cleveland-Innes, 2013); instructors may ease the students in via pre-course surveys or introductory discussion boards.

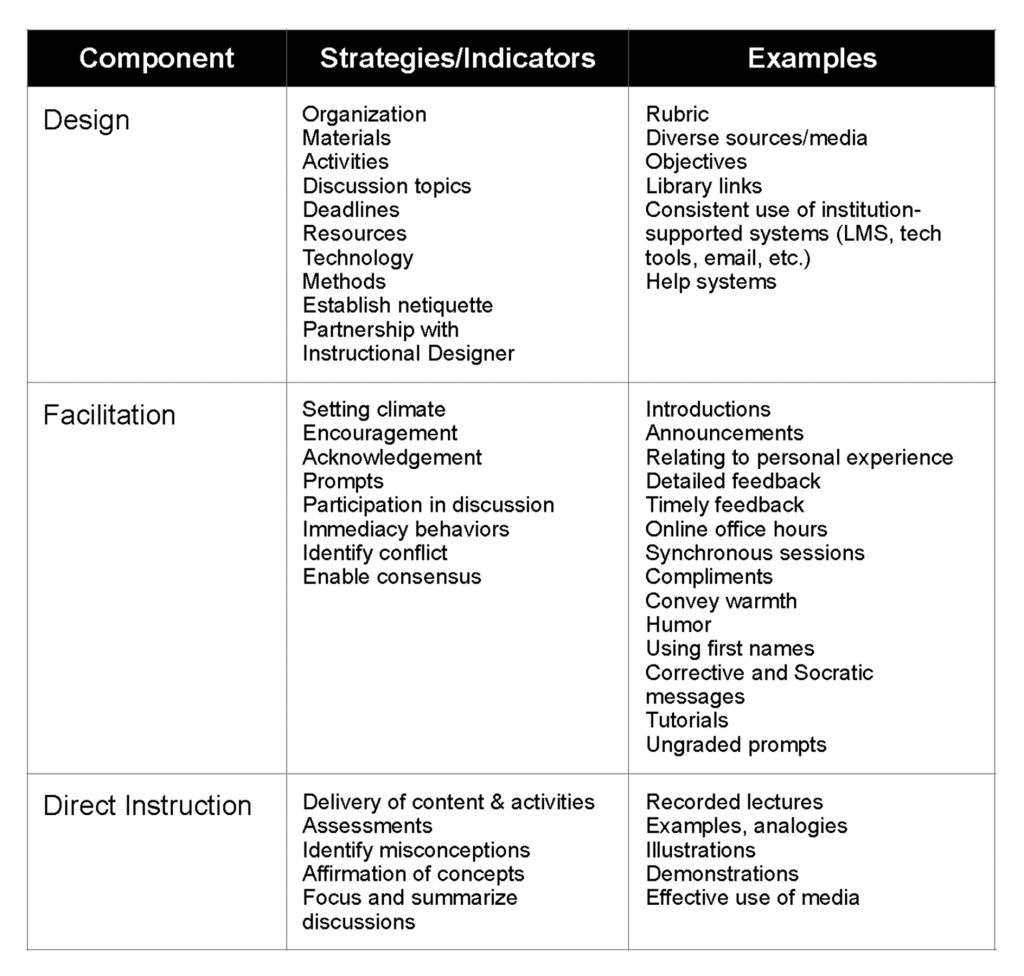

Instructor presence can be demonstrated in a variety of ways (see Table 1), through written, audio, and video communications, as well as synchronous sessions or chats. While Garrison et al. (2000) express that in the asynchronous environment, text communications with the instructor and fellow students provide an advantage by allowing time for reflection, which can encourage “discipline and rigor” (p. 90) in the community, Lamb & Callison (2005) note that misinterpretation of written words in Internet communications can be problematic. As an example, “Humor is helpful, but there is sometimes a fine line between humor and criticism” (Lamb & Callison, 2005, p. 31). Additionally, the lag in response time and lack of visual contact in an asynchronous environment can cause anxiety for students (Irwin & Berge, 2006; McDonald, 2002). Ice et al. (2007) demonstrate that the use of audio feedback could result in student perceptions of instructor caring and involvement, as well as providing tone and inflection to express nuance. Russell (2006) voices concern for loss of empathy due to time and physical distance between students. Regardless of where they are geographically, students yearn for caring, present instructors who project the human touch into their courses (Pacansky-Brock, 2014).

Table 1. Indicators and Examples of Teaching/Instructor Presence

Social Presence

Remembering Dewey’s (1929), Vygotsky’s (1978) and Moore’s (1993) shared perspective of the social nature of education, it seems that social presence is especially vital to online education where there is marked distance between instructors and students. Social presence is described as the student’s ability to project their personality into the community (Garrison et al., 2000; Irwin & Berge, 2006). Students experience emotional engagement through social presence (Nafukho, 2014), and Sull (2014) believes it is a fusion of engagement, motivation, and rapport between the students and the instructor. Lang (2015) proposes a “pedagogy of presence,” (para. 8) referring to the value of faculty presence in positively affecting learning outcomes in online education. Lang (2015) stresses that what students find most memorable about college is personal relationships, and posits that research does not address the correlation between personal relationships and learning outcomes.

Garrison (2007) identifies three aspects of social presence as effective instruction, open communication, and group connectedness, which can be affected by collaborative and individual activities. Nagel and Kotzé (2010) found that social presence indicates the feeling of belonging to the community, and a sense of closeness results from active social presence, also termed connectedness (Ekmekci, 2013; Irwin & Berge, 2006). “Connectedness is more than student empathy for one another; instead it becomes a vital tool necessary for successful navigation through the learning experience” (Irwin & Berge, 2006, p. 3). The concept of social presence can be assigned to the instructor as well as the students. When discussing the instructor’s social presence, it is presumed that it is an emotional projection that makes the instructor more human and personable (Burkle & Cleveland-Innes, 2013; Meyer et al., 2009).

Picciano (2002) cautions that interaction and social presence are not synonymous. For instance, a student may interact within a discussion board and not necessarily be connected to the course community. Students’ motivation throughout the course can be influenced by their skills, how they participate in and complete activities, and their motivation to learn (Garrison, et al., 2000). Social presence must shift over the course of study as group dynamics change and participants learn about one another (Garrison, 2007). The continuing connection requires a focus on the academic purpose and activities of the course, open and intentional communication, and a sense of respect among the students as they create purposeful relationships (Garrison, 2007; Irwin & Berge, 2006). Kilgore’s & Lowenthal’s (2015) study indicate a Community of Inquiry can be established in a short time (in this case, 4 weeks), but the trust aspect of social presence was decidedly compromised as participants felt they could not question one another because there was not enough time to establish a sense of boundaries and an atmosphere of safety.

A strong community is imperative in higher education learning and helps reduce feelings of isolation in online learning. Characteristics of a learning community include students’ sense of trust, belonging and mutual interdependence, and shared educational goals through interaction with other course participants (Rovai, 2002). Students establish their own social presence through sharing of personal experiences related to the course subject matter within a section or an entire course (Kilgore & Lowenthal, 2015). Peer review can be an effective tool for collaboration as well (Ekmekci, 2013).

When online instructors take advantage of collaboration tools, social learning is promoted both in coursework and outside communication (Palloff & Pratt, 2003). Collaboration can enhance relationships through sharing of resources, encouragement and advice, and can also foster respect between students (Kilgore & Lowenthal, 2015; Irwin & Berge, 2006; Palloff & Pratt, 2003). Social presence can go beyond the boundaries of knowledge construction. Meyer et al. (2006) tie social presence to student retention in a study of adult learners in a certification program. Sixty of 62 participants completed the program, and retention was tied to the ability of the instructor to create social presence through design and facilitation. Synchronous activities may mirror classroom interaction, adding to social presence (Marmon, 2015). However, Russell (2006) suggests that social interaction must be planned into the curriculum; Kilgore & Lowenthal (2015) agree, particularly in a course with many participants.

Cognitive Presence

Garrison et al. (2000) explain that cognitive presence “can best be understood in the context of a general model of critical thinking” (p. 98), and that “what to think…is domain-specific and context-dependent” (p.98). Irwin and Berge (2006) suggest examining cognitive presence with situated learning theory, which is based in “social development theory and constructivism” (p. 3), and takes into account the context of the learning environment as a significant influencer on the learner. In the CoI model, cognitive presence is integral: “the extent to which cognitive presence is created and sustained in a community of inquiry is partly dependent on how communication is restricted or encouraged” (Garrison et al., 2000, p.93). Cognitive presence is also evident when students purposefully and collaboratively construct knowledge (Garrison, et al., 2001), resulting in deep meaning, retained knowledge, and critical thinking (Nagel & Kotzé, 2010).

One of the advantages for the instructor in an online environment is that there is a “concrete interactive trail” (Lamb & Callison, 2005, p. 30), leaving the instructor with a tool for analyzing the paths of cognitive presence throughout the course and among students. Several studies showed that students with high social presence also had increased perceptions of quality learning as well as satisfaction with their instructors (Akyol & Garrison, 2008; Picciano, 2002; Richardson & Swan, 2003). Picciano’s (2002) study included both examinations and written assignments; correlations were highest in the written assessment while the exam was considered asocial and therefore not equated with social presence. However, student satisfaction was high with both individual and group activities.

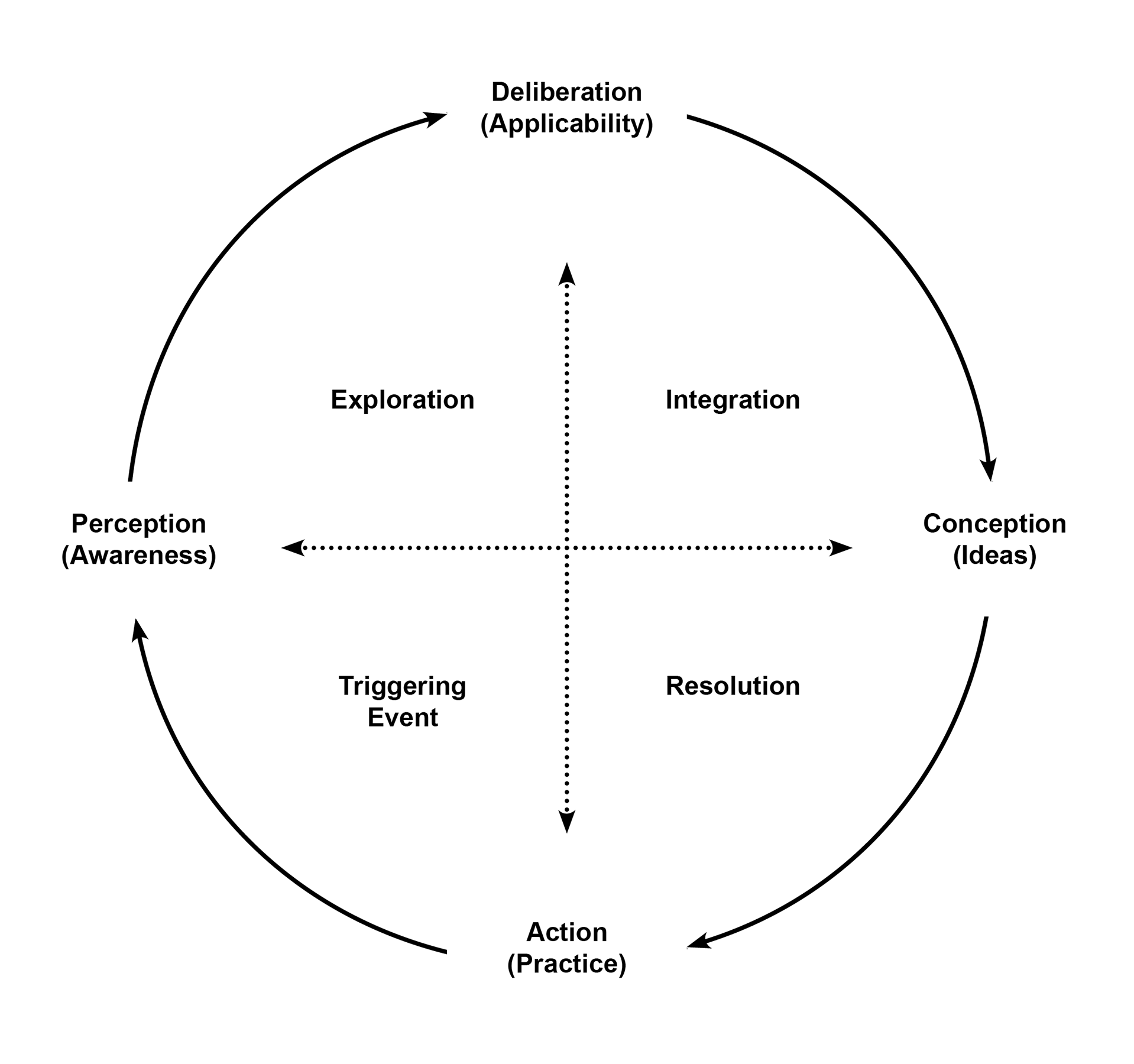

Garrison et al. (2000) consider cognitive presence a “vital element in critical thinking a process and outcome that is frequently presented as the ostensible goal of all higher education” (p. 89). In CoI, critical thinking is a process based on Dewey’s (1933) model of practical inquiry and the “means to create cognitive presence” (Garrison, et al., 2001, p. 11). Dewey’s (1933) model was centered on students’ experiences, including three situations: pre-reflection, reflection, and post-reflection (resolution). Garrison et al. (2000) designed their model (see Figure 2) to represent the stages of practical inquiry. The vertical axis signifies reflection on practice, while the horizontal axis is the assimilation of information and construction of knowledge. The quadrants are cognitive presence indicators, illustrating the sequence of critical thinking:

- Triggering event – A question or problem;

- Exploration – The search for information to answer the question or solve the problem;

- Integration – Making sense of the knowledge found; and

- Resolution – Applying the idea for confirmation.

Garrison et al. (2001) later refined the model and considered integration as a pivotal part of the inquiry process. They noted that it can be difficult to recognize, and must “be inferred from communication within the community of inquiry” (p. 10). In this phase, “teaching presence is essential in moving the process to more-advanced stages of critical thinking and cognitive development” (p. 10), because without it, students may remain comfortable in the exploration phase, and not move into integration or resolution.

Figure 2. Practical Inquiry (Garrison et al., 2000, 2001)

Correlation of Teaching, Social, and Cognitive Presences

Relationships between teaching, social, and cognitive presences are visually demonstrated in the Community of Inquiry model designed by Garrison et al. (2000). The literature provides evidence to support the model. According to Garrison (2007), there are pedagogical implications to understanding the correlation between presences. “Balancing socio-emotional interaction, building group cohesion, and facilitating and modeling respectful discourse is essential for productive inquiry” (Garrison, 2007, p. 69). Shea and Bidjerano (2009) conducted a study, validating relationships between the presences in a CoI. Using a sample of over 2,100 students, they determine that “70% of the variation in students’ levels of cognitive presence can be modeled based on their reports of their instructors’ skills in fostering teaching and social presence” (p 551). Instructor presence is required for social presence to occur, and social presence is necessary for cognitive presence (Akyol & Garrison, 2008; Garrison, et al., 2001; Shea & Bidjerano, 2009). Furthermore, Shea & Bidjerano (2009) purport that “teaching presence predicts variance in cognitive presences directly” (p. 545). As an example, they found that when the instructor focused and participated in discussion, teaching presence correlated to higher cognitive presence.

According to Garrison et al. (2000), cognitive presence has greater sustainability when social presence has already been established and there is a higher quality of knowledge construction when collaboration is present. Ekmekci (2013) advocates for the creation of feedback loops to allow for adjustments throughout the course. Palloff & Pratt (2003) agree, adding that modification of the course from one term to the next is also valuable. Furthermore, “instructors and learners must continuously seek to be creative and innovative in their teaching and learning, respectively” (Nafukho, 2014, p. 787).

Cognitive presence was directly affected by teaching presence, according to Ice et al. (2007), when the extensive use of audio feedback resulted in increased content retention and deep understanding within a more relaxed learning environment. Immediacy behaviors of the instructor, such as humor, social sharing, and greetings, contribute to social presence and student satisfaction with the instructor (Richardson & Swan, 2003). According to Picciano (2002), social presence, as fostered by teaching presence, supports cognitive presence to facilitate the process of critical thinking. Community helps students understand that they are not alone, and in a sense, are responsible for others in the class as well (Irwin & Berge, 2006). Participants in a study conducted by Yang et al. (2010) acknowledged that interaction between themselves and their peers and instructors improved their learning.

Rourke and Kanuka (2009) conducted an extensive analysis of studies using the CoI model. The purpose and outcome of the review was to refute what they considered the central claim of CoI as “deep and meaningful learning” (p. 19). Rourke & Kanuka (2009) found no “clear instances of cognitive presence” (p. 39). They argued that research in cognitive presence primarily focuses on the perceptions of student learning rather than seeking evidence of measured learning (Rourke & Kanuka, 2009). They asserted that in over 250 studies, they found just five that attempted to measure student learning, and of those, all recounted only self-reported learning by students. Rourke and Kanuka (2009) considered this dismal, and that cognition (not just learning processes) should be the primary focus of the bulk of the research, as teaching and social presence were irrelevant if cognition was absent. In their published response, Akyol et al. (2009) acknowledged the benefit of constructive critiques in order to grow and evolve. However, they point out the central claim of the model was misrepresented by Rourke and Kanuka, because Garrison et al. (2000) focus on creating a process model for researchers study approaches to learning. Akyol et al. (2009) stated that cognitive presence “includes understanding an issue or problem searching for relevant information; connecting and integrating information; and actively confirming the understanding in a collaborative and reflective learning process” (p. 125). Furthermore, Akyol et al. (2009) pointed out that in several of the studies Rourke and Kanuka chose as examples, the inabilities of students to reach integration and resolution were attributed to shortcomings of teaching presence. Even in the absence of measured cognition, Picciano (2002) concludes “ultimately, student perceptions of their learning may be as good as other measures because these perceptions may be the catalyst for continuing to pursue coursework and other learning opportunities” (p. 2).

Implications for Further Research

The CoI framework is likely to remain a predominant theory in research of online learning well into the future, as conceived by its designers, Garrison et al. (2000). However with continual changes that online learning is likely to experience over the next several decades, along with the technologies that will be driving it, there may never be an ideal balance among the presences (Swan, Garrison, & Richardson, 2009). Additional ever-evolving variables remain in the equation: teaching style, training, and development of presence; the social comfort of students; cultures, ethnicities, and language; class sizes; familiarity with concepts, delivery methods and tools; learning management systems; and more. In light of this unpredictability, it seems clear that researchers may have a monumental task to identify best practices. However, Shea et al. (2003) followed up on their study about teaching presence to identify the effects of resources applied to instructional design, organization, faculty development, and a new learning management system, and found the changes resulted in higher ratings for teaching presence.

Similar studies with a continuous improvement approach may be valuable to institutions and online educators. Modifications made over multiple iterations of a course (e.g., faculty development in presence, or integration of collaboration tools and technology), may identify opportunities for establishing and maintaining higher quality online courses and programs. One such study could compare learning outcomes between courses intentionally designed to foster teaching presence, in particular, coupled with faculty trained in the CoI framework, against the same courses without the intentional design and trained faculty.

Higher education institutions will continue to face difficulties developing long-term online education strategies unless there is a growing body of evidence for a more predictable way of anticipating trends in both technology and the needs of online students. Burkle & Cleveland-Innes (2013) suggest that institutional policies will require significant revisions, and faculty will need to embrace their new roles as online instructors.

Conclusion

This literature review examines the role of instructor presence in online learning. A broad range of perspectives is covered on the three presences found in the Community of Inquiry model introduced by Garrison et al. (2000). Teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence are considered in literature not connected to CoI, which leads me to believe that Garrison et al. (2000) designed a sustainable process model for research in online learning communities.

Personal experiences in my graduate studies reflect positive learning perceptions and outcomes as a result of instructor presence. The effects of strong instructor presence, for me personally, have included motivation, engagement, satisfaction with the courses and instructors, and a heightened sense of learning. Classes in which the instructors’ presence is weak or inconsistent are not nearly as engaging and result in feelings of anxiety.

The combination of this review and my own personal experience has deepened my conviction for the need for faculty development focused on online instructor presence. Allen & Seaman (2015) report that higher education faculty acceptance of the “value and legitimacy” (p. 21) of online learning has remained static since 2003, at just 28%, but among those who have already taught online, acceptance is much higher. It seems that if faculty are still not convinced of online learning as a legitimate delivery method, convincing them that they need to apply effort towards creating presence may be a dim proposition. For instance, Preisman (2014) conducted a study of teaching presence within her own courses. Countering the evidence that most studies examine presence from the students’ point of view, Preisman set out to determine whether outcomes were worth the investment of time to infuse presence into her courses. While her findings did not demonstrate a significant value in putting forth the effort, Preisman did conclude that being present was needed as opposed to having presence (2014). Reiger’s (2014) view highlights the skepticism Preisman may not have overcome.

Perhaps the single most effective online classroom intervention for nontraditional students is to heighten the sense of the instructor’s presence in the course. More faculty members are being asked to add online courses to their teaching load. Although such assignments often are initially viewed with deep skepticism by faculty who have themselves been educated in an exclusively face-to-face format, faculty views evolve once it becomes clear that quality content and quality courses can be delivered online (p. 80).

One overwhelming variable, however, is whether higher education instructors will truly understand that there is a difference between teaching online versus the traditional classroom, and perhaps most importantly, whether they have received instruction in how to teach at all. Recognizing that, I have come to appreciate that helping faculty develop into being online instructors is critical to delivering quality, successful online programs. Institutions can learn about their own instructors by consistently including questions with CoI elements in end-of-term surveys to determine levels of teaching, social, and cognitive presences in their online courses.

In order for faculty development to be successful, institutions must support and value the efforts. Berge & Clark (2009) suggest that teachers must experience online learning as a student in order to understand what it feels like on the other side of the computer screen. When instructors experience similar frustrations and accomplishments as students, they can empathize with the students and understand how online teaching requires enhanced skills. In particular, flexibility is a key to teaching learners who are always connected to technology (Palloff & Pratt, 2003). “Today’s students are no longer the people our (U.S.) educational system was designed to teach” (Prensky, 2012, p. 68). Burkle and Cleveland-Innes (2013) agree that these students think and process material differently than any other generation. I believe it will be critical for higher education faculty to be trained in not only online teaching methods to promote presence, but also techniques to reach the increasingly tech-centric student population that is becoming the norm.

References

Akyol, Z., Arbaugh, J. B., Cleveland-Innes, M., Garrison, D. R., Ice, P., Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2009). A response to the review of the community of inquiry framework. Journal of Distance Education (Online), 23(2), 123.

Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. R. (2008). The development of a community of inquiry over time in an online course: Understanding the progression and integration of social, cognitive and teaching presence. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(3-4), 3.

Allen, I. E. & Seaman, J. (2015). Grade level: Tracking online education in the United States. Online Learning Consortium.

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001) Assessing teaching presence in computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 5(2).

Berge, Z. & Clark, T. (2009). Virtual schools: What every education leader should know. White paper for the Virtual School Education Summit, Ft. Lauderdale, FL.

Burkle, M., & Cleveland-Innes, M. (2013). Defining the Role Adjustment Profile of Learners and Instructors Online. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 17(1), 73-87.

Chen, P., Gonyea, R., & Kuh, G. (2008). Learning at a distance: Engaged or not? Journal of Education 4(3).

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE bulletin, 3, 7.

Dewey, J. (1929). My pedagogic creed. In D. Flinders & S. Thornton (Eds.). (2009). The Curriculum Studies Reader. New York, NY: Routledge.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think (rev. ed.). Boston, MA: D. C. Heath.

Dzubinski, L. (2014). Teaching presence: Co-creating a multi-national online learning community in an asynchronous classroom. Online Learning: Official Journal of the Online Learning Consortium, 18(2).

Ekmekci, O. (2013). Being there: Establishing instructor presence in an online learning environment. Higher Education Studies 3(1), 29-38.

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online Community of Inquiry Review: Social, Cognitive, and Teaching Presence Issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61-72.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2), 87-105.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2001). Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. American Journal of distance education, 15(1), 7-23.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2010). The first decade of the community of inquiry framework: A retrospective. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1–2), 5-9.

Garrison, D. R., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Fung, T. S. (2009). Exploring causal relationships among teaching, cognitive and social presence: Student perceptions of the community of inquiry framework. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1), 31-36.

Ice, P., Curtis, R., Phillips, P., & Wells, J. (2007). Using asynchronous audio feedback to enhance teaching presence and students’ sense of community. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(2), 3-25.

International Association for K-12 Online Learning. (2011). National standards for quality online teaching.

Irwin, C., & Berge, Z. (2006). Socialization in the online classroom. E-Journal of Instructional Science and Technology, 9(1).

Kilgore, W. & Lowenthal, P. (2015). The human element MOOC. In R. W. Wright (Ed.), Student-teacher interaction in online learning environments. Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference.

Lamb, A., & Callison, D. (2005). Online learning and virtual schools. School Library Media Activities Monthly, XXI(9), 7.

Lang. J. (January 19, 2015). Waiting for us to notice them. Chronicle of Higher Education.

Lorenzo, G., & Moore, J. (2002). Five pillars of quality online education. The Sloan consortium report to the nation, 15-09.

Marmon, M. (2015). The value of social presence in developing student satisfaction and learning outcomes in online learning environments. In R. W. Wright. (Ed), Student-teacher interaction in online learning environments. Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference.

McDonald, J. (2002). Is “as good as face-to-face” as good as it gets? Journal for Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6(2), 10-23.

McGlynn, A. P. (2005). Teaching millennials, our newest cultural cohort. Education Digest: Essential Readings Condensed for Quick Review, 71(4), 12-16.

Moore, M. G. (1989). Three types of interaction. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 8(6), 1-7.

Moore, M. G. (1993). Theory of transactional distance. Theoretical Principles of Distance Education 1, 22-38.

Nafukho, F. M. (2014). Strengthening student engagement: What do students want in online courses? European Journal of Training and Development 38(9), 782-802.

Nagel, L., & Kotzé, T. G. (2010). Supersizing e-learning: What a CoI survey reveals about teaching presence in a large online class. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1), 45-51.

National Survey for Student Engagement, (2014). Bringing the institutions into focus: Annual results 2014. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research.

Noel-Levitz (2014). 2014-15 national online learners’ priorities report. Coralville, IA: Noel-Levitz.

Oblinger, D. (2014). Designed to engage. Educause Review, 49(5), 13-32.

Pacansky-Brock, M. (2013). Humanizing your online class. (Webinar) https://www.insidehighered.com/audio/2013/10/09/humanizing-your-online-class

Pacansky-Brock, M. (2014). Learning out loud: Increasing voluntary voice comments in online classes. In P. R. Lowenthal, C. S. York, & J. C. Richardson (Eds.), Online learning: Common misconceptions, benefits and challenges, (pp. 99-114). Hauppage, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

Palloff, R. & Pratt, K. (2003). The virtual student. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Palloff, R. & Pratt, K. (2011). The excellent online instructor: Strategies for professional development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Picciano, A. G, (2002). Beyond student perceptions: Issues of interaction, presence, and performance in an online course. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 6(1), 21-40.

Preisman, K. (2014). Teaching presence in online education: From the instructor’s point-of-view. Online Learning: Official Journal of the Online Learning Consortium, 18(3).

Prensky, M. (2012). From digital immigrants to digital wisdom. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Quality Matters. (2014). Standards from the QM higher education rubric. (5th ed.).

Reiger, P. (2014). Using technology to engage the nontraditional student. Educause Review, 49(5), 70-88.

Robinson, C. C., & Hullinger, H. (2008). New benchmarks in higher education: Student engagement in online learning. Journal of Education for Business, 84(2), 101-108.

Rourke, L. & Kanuka, H. (2009). Learning in communities of inquiry: A review of the literature. Journal of Distance Education (Online), 23(1), 19.

Rovai, A. P. (2002). Development of an instrument to measure classroom community. The Internet and Higher Education, 5(3), 197-211. doi:10.1016/S1096-7516(02)00102-1

Russell, G. (2006). Implications of virtual schooling for socialization and community. In S. Dasgupta. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Virtual Communities and Technologies (pp. 253-257). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Savery, J. R. (2005). BE VOCAL: Characteristics of successful online instructors. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 4(2), 141-152.

Shea, P., & Bidjerano, T. (2009). Community of inquiry as a theoretical framework to foster “epistemic engagement” and “cognitive presence” in online education. Computers & Education, 52(3), 543-553.

Shea, P. J., Pickett, A. M., & Pelz, W. E. (2003). A follow-up investigation of “teaching presence” in the SUNY Learning Network. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(2), 61-80.

Shea, P., Li, C. S., Swan, K., & Pickett, A. (2005). Developing learning community in online asynchronous college courses: The role of teaching presence. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 9(4), 59-82.

Stavredes, T. M., & Herder, T. M. (2014). Engaging students in an online environment. In S. R. Harper & S. J. Quaye (Eds.), Student engagement in higher education: Theoretical perspectives and practical approaches for diverse populations (2nd ed.), (pp. 257-269). Florence, KY: Taylor and Francis.

Swan, K., Garrison, D. R. & Richardson, J. C. (2009). A constructivist approach to online learning: the Community of Inquiry framework. In C. R. Payne (Ed.), Information Technology and Constructivism in Higher Education: Progressive Learning Frameworks. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 43-57.

U.S. Department of Education National Center for Educational Statistics. (2015).

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. In M. Gauvain & M. Cole (Eds.), (1997). Readings on the development of children (2nd ed.).

Weimer, M. (2012). Talk about teaching that benefits beginners and those who mentor them. In R. Kelly (Ed.), Faculty focus: 12 tips for improving your faculty development plan. Madison, WI: Magna Publications, Inc.

Xie, K., Miller, N. C., & Allison, J. R. (2013). Toward a social conflict evolution model: Examining the adverse power of conflictual social interaction in online learning. Computers & Education, 63, 404-415.

Yang, Y., Yeh, H., & Wong, W. (2010). The influence of social interaction on meaning construction in a virtual community. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(2), 287-306.

Additional Reading

Abrami, P., Bernard, R., Bures, E., Borokhovski, E., & Tamim, R. (2011). Interaction in distance education and online learning: using evidence and theory to improve practice. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 23(2-3), 82-103.

Bonk, C. & Khoo, E. (2014). Adding some tec-variety: 100+ activities for motivating and retaining learners online. Bloomington, IN: Open World Books.

Boston, W., Díaz, S. R., Gibson, A. M., Ice, P., Richardson, J., & Swan, K. (2009). An exploration of the relationship between indicators of the community of inquiry framework and retention in online programs. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 13(3), 67-83.

Bryson, C. (2014). Understanding and developing student engagement. New York, NY: Routledge.

Conrad, R. M., & Donaldson, J. A. (2012). Continuing to engage the online learner: More activities and resources for creative instruction (Vol. 35). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Dabbagh, N. (2007). The online learner: Characteristics and pedagogical implications. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education 7(3), 217-226.

Dirksen, J. (2012). Design for how people learn. Berkeley, CA: New Riders.

Dixson, M. (2010). Creating effective student engagement in online courses: What do students find engaging? Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(2), 1-13.

Ko, S., & Rossen, S. (2010). Teaching online: A practical guide. New York, NY: Routledge.

Lear, J. L., Isernhagen, J. C., LaCost, B. A., & King, J. W. (2009). Instructor presence for Web-based classes. The Journal of Research in Business Education, 51(2), 86-98.

Lehman, R. & Conceiçao, S. (2010). Creating a sense of presence in online teaching: How to “be there” for distance learners. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Lehman, R. & Conceiçao, S. (2013). Motivating and retaining online students: research-based strategies that work. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

McDonald, J., Zydney, J., Dichter, A., & McDonald, E. (2012). Going online with protocols: New tools for teaching and learning. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

McGlynn, A. P. (2005). Teaching millennials, our newest cultural cohort. Education Digest: Essential Readings Condensed for Quick Review, 71(4), 12-16.

McGlynn, A. P. (2010). Millennials – the “always connected” generation. The Hispanic Outlook in Higher Education, 20(22), 14.

Moll, M. (1998). No more teachers, no more schools: information technology and the “deschooled” society. Technology in Society, 20(3), 357-369.

Moore, M. G. & Kearsley, G. (2011). Distance education: A systems view of online learning. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

Pacansky-Brock, M. (2013). Best practices for teaching with emerging technologies. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Palloff, R. & Pratt, K. (2013). Lessons from the virtual classroom: The realities of online teaching (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Park, J. H. & Choi, H. J. (2009). Factors influencing adult learners’ decision to drop out or persist in online learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 12(4), 207-217.

Pollard, H., Minor, M., & Swanson, A. (2014). Instructor social presence within the community of inquiry framework and its impact on classroom community and the learning environment. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 17(2).

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants part 2: Do they really think differently? On the Horizon, 9(6), 1-6.

Prensky, M. (2010). Teaching digital natives: Partnering for real learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Prensky, M. (2012). Brain gain: technology and the quest for digital wisdom. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Roblyer, M. D. & Wiencke, W. R. (2004). Exploring the interaction equation: Validating a rubric to assess and encourage interaction in distance courses. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 8(4), 25-37.

Ruey, S. (2010). A case study of constructivist instructional strategies for adult online learning. British Journal of Educational Technology 41(5), 706-720.

Thormann, J. & Zimmerman, I. (2012). The complete step-by-step guide to designing & teaching online courses. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Vonderwell, S. (2003). An examination of asynchronous communication experiences and perspectives of students in an online course: a case study. The Internet and Higher Education 6, 77-90.

Watson, J., Gemin, B., & North American Council for Online Learning (2008). Promising practices in online learning: Socialization in online programs. North American Council for Online Learning.

Key Words and Definitions

Cognitive Presence: The perception of the level of meaning construction and critical reflection of course content in the Community of Inquiry model resulting from interaction with the instructor, other students and the content (Garrison et al., 2000).

Community of Inquiry (CoI): A process model for online community which describes the group of learners and instructor(s) tied to specific learning objectives and the interaction of teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence (Garrison et al., 2000, 2001; Anderson et al., 2001).

Immediacy: A measure of the psychological distance between instructors and students. Verbal immediacy includes the use of humor, encouragement, and use of student names, while non-verbal immediacy includes gestures, facial expression, and eye contact (Richardson & Swan, 2003).

Online Learning: Several terms are used interchangeably with online learning, including virtual schools cyber- schools, e-learning, and distance education (Lamb & Callison, 2005). According to U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (2015) distance education is delivered synchronously or asynchronously by means of technologies that aid interactions between instructors and students who are separated from one another. While online learning is identified with K-12 as well, throughout this review the term is consistent with this definition primarily in relation to higher education.

Social Presence: In the online academic setting, the sense of community and belonging in the course through interactions with peers and instructors, within a trusting environment (Garrison et al., 2000; Garrison, Cleveland-Innes & Fung, 2009; Ice, Curtis, Phillips & Wells, 2007; Shea, Pickett & Pelz, 2003). Social presence is sometimes considered to be a component of teaching presence and at others more of an umbrella term covering both instructors and students and their collective interactions.

Teaching/Instructor Presence: The role of the instructor in design, facilitation, and direct instruction in such a way as to create opportunities for social interaction between him/herself and the student and between students to bring about positive learning outcomes (Anderson, Rourke, Garrison & Archer, 2001; Shea, Pickett & Pelz, 2003).