4 Voice and Video Instructor Feedback to Enhance Instructor Presence

Helen J. DeWaard

This chapter examines instructor feedback using audio and video technologies to humanize online learning spaces. An explanation and definition of feedback is presented. The role of feedback is explored. Humanizing elements in feedback incorporate the content, strategies, sequence, and tools. Content elements include the focus, function, valence, clarity, and specificity. Feedback strategies incorporate timing, amount, audience, and mode. Considering the sequence for feedback – listening, summarize-explain-redirect-resubmit (SE2R), connecting, creating, and tracking will assist instructors to humanize their actions. A survey of available technologies and tools to create feedback messages with text, graphic, audio, image, and video, and integrated multimodal production technologies is presented. A design model for the integration of feedback into online communities of inquiry is summarized. Issues relevant to audio and video feedback – time, training, acceptance, application, and openness are examined. Finally, research and emerging trends with audio and video feedback are shared.

Introduction

Feedback is a recursive loop of practice-feedback-performance-judgement, that influences teaching and learning in online spaces. Within a community of inquiry (CoI) model (Garrison, Cleveland-Innes, & Vaugh, n.d.) teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence is affected and shaped by feedback. The systemic application of feedback from every member of the learning community influences and alters the effects and outcomes for individuals, and the overall learning experience within an online course. Practices and procedures to humanize comments and observations is integrated into the content, strategies and sequences of feedback. Tips and issues for managing the processes and tools to integrate a human element into digitally created and shared feedback will be explored.

Background

Garrison, Anderson & Archer (2001) define teaching presence as “the design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes.” Teaching presence includes instructional management through defining and initiating discussion topics, building understanding by sharing personal meaning, and direct instruction by focused discussion (Garrison, et. al., n.d.). Feedback is an essential component of teaching presence. Methods, strategies, and mechanisms used to distribute feedback will influence and shape the management, understanding, and instruction in an online course.

What is feedback? Feedback is information about an individual’s reaction or response to a product or performance task. It is more than a behaviouristic view of cause and effect or a reinforcement mechanism (Brookhart, 2008, p. 3). Feedback is used as a means to improve performance. The process or system of learning and teaching within an online course can be modified or controlled using feedback. Hattie and Temperley (2007) identify four areas of feedback: about a task, about the process of a task, about self-regulation and about the individual learner as a person (Brookhart, 2008, p. 4).

Feedback is an essential element of instruction throughout the community inquiry process. Effective feedback includes the following attributes: building trust, clearly communicated, user-friendly, specific, focused, differentiated, timely, invites follow-up, and is actionable (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013 p. 62-63). Feedback works to support focused discussions, questioning, injecting new knowledge, providing technical support, encouraging participation, and modeling online behaviour. Feedback directly connects to the designed activities, learning outcomes and the facilitation of discourse and course content. Feedback addresses cognitive and motivational factors (Brookhart, 2008, p. 2). Feed-forward refers to proactive, preventative feedback used to avoid or respond to known or perceived issues, problematic processes, and challenging concepts or complex tasks.

Feedback can enhance and improve outcomes within teaching and learning. While feedback is often considered to be the responsibility of the instructor, feedback occurs laterally and hierarchically, from student to student, instructor to student, and student to instructor. Peer feedback is becoming more prevalent in online learning, with explicit processes to model, facilitate, support, and reward leadership and participation (CIDER webinar, 2015). Formal grading of course assignments using a mark, without constructive comments, is no longer considered an effective feedback mechanism (Barnes, 2015, p. 4). Applying an outcome-based practice-feedback-performance loop using a summarize-explain-redirect-resubmit (SE2R) formula will improve student learning (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013, p. 62; Barnes, 2015, p. 33).

Mechanized and automated feedback, frequently built into online learning environments, can de-humanize online learning. While effective feedback is time consuming and challenging for instructors to manage (Hummel, 2006, p. 1), a human element can be instilled through quality text, voice, and video responses. A humanized teacher presence will model and prioritize presenting a human face and voice in the feedback process by creating and sharing a human response wherever and whenever possible.

Humanizing Teacher Feedback – Content, Strategies, Considerations, Tools

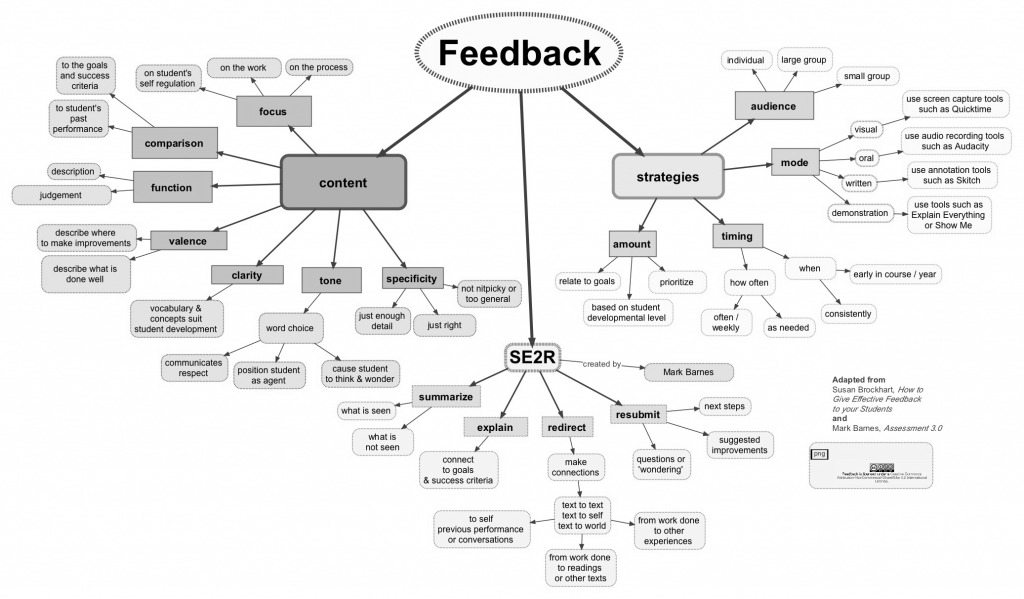

Humanized feedback messages are created using text, image, audio, and video. Feedback content is structured through focus, comparison, function, valence, clarity, tone, and specificity (Brookhart, 2008, p. 6-7). Strategies for the creation, distribution, and monitoring of feedback include human decisions about the amount, timing, mode and audience of the feedback (Brookhart, 2008, p. 10-18). Considerations for the process and management of collecting, creating, and distributing feedback include listening (Sircy, 2015), SE2R (Barnes, 2015 p. 34) making connections, scripting, and tracking. Process oriented feedback (feedforward or feedthrough) for complex online learning tasks should focus on student problem-solving, developing schema, cueing cognition, and developing solutions. Digital tools to create and distribute feedback incorporate text-based, augmented image, audio recorded or video captured options.

Figure 1.0 – Feedback

Content

Humanizing the content of feedback keeps the student and the learning at the forefront. Gathering student images, avatars, and background information can assist teachers to know the learner as a person and to help them visualize their students as individuals when feedback is written. Preparing a collection of feedback comments for learning tasks in advance, using a rubric or standard set of criteria, can streamline comment creation. Humanizing the content of feedback communicates the instructor’s belief that each student can succeed, that they care for their students, and that rigorous and shared inquiry will lead to enhanced learning.

Brookhart (2008) identifies that feedback content should focus on the learning task, the process to achieve the task, self-regulation to complete the task, and feedback to the student as an individual learner (p. 20). Brookhart also reveals that quality feedback includes comments on strengths and weaknesses in a performance while not bypassing the student who created the work. Suggestions on the process or strategies should include insights for improvement. Avoiding personal compliments or digs will help ensure the student is well positioned to accept and act on the feedback (Brookhart, 2008, p. 20).

Effective feedback compares and contrasts student work against a set of established criterion, goals, or learning targets. Instructors or students can compare the quality or quantity of what is seen, not seen, or progress toward an expected or established range. Feedback that compares the process or product against ‘best practice’ or an established rubric allows a student to make decisions about next steps. To humanize feedback and respect the work of individual learners, instructors in online learning environments should avoid comparing student work in relation to other students’ accomplishments. This sets up winners and losers, resulting in unnecessary competition, performance anxiety, or hurt feelings.

The content of feedback will be filtered and interpreted through a student’s previous experiences and current understanding. Evaluation is often an unintended result that can be avoided when using audio or video feedback tools. Engaging students in audio or video conversations can enhance the function of feedback where description rather than judgement can be communicated or clarified. Screen sharing or screencasting can effectively show and elaborate on what is observed in a student’s performance or highlight missing elements in comparison to the learning targets. Recording these conversations ensures that students can return, revisit, and review the descriptive feedback presented.

Valence refers to the perceived positive or critical nature of feedback. Instructors can humanize their feedback by focusing on achievement with positive comments or suggestions for improvement. Context impacts how students perceive feedback valence so utilizing audio or video can provide opportunities to explain, describe or clarify context, observe or improve. Valence impacts the likelihood that action will result from the feedback since positive perceptions foster an improvement in learning.

Feedback clarity ensures that feedback is understood and is improved when simple, specific vocabulary and sentence structures are applied. Clarity minimizes confusion when students come from diverse cultures, languages, and abilities. Word selection and drafting key points prior to recording asynchronous audio or video messages will help instructors craft clear feedback. During synchronous conversations, asking clarifying questions can ensure that feedback is understood.

Emotions are communicated and perceived through the tone of a feedback message. Tone in audio and video messages can convey a playful, serious, angry, friendly or confident nature. Tone inspires or encourages student learning so selecting words and applying voice intonation to audio and video messages should convey an instructor’s belief in student agency (Brookhart, 2008, p. 34). Within audio and video messages tone can be inferred from facial expressions, voice volume, cadence, pitch, pacing, timber, register and prosody (Treasure, 2014). Word choice should convey a respectful tone and situate students as agents for action. Instructors need to ensure that feedback tone matches the circumstance and context.

Feedback specificity relies on the ‘Goldilocks principle’ – a scale from too narrow, too broad or just right (Brookhart, 2008, p. 33). Apply sufficient detail and focus without doing the work for the student. Show rather than tell. Point the work toward learning targets while describing strategies that students can apply to move toward success. Instructor feedback varies in specificity as the online course progresses, with less specificity needed toward the end of the schedule. Specificity helps instructors create brief, succinct and concrete audio or video messages.

Strategies

Humanizing the amount of feedback within online learning environments is dependent on technical proficiency, the time available to instructors and students, the tools and supports utilized, the complexity of the course content, and student needs. Gauging the amount of feedback over time is reliant on the instructor’s experience and expertise with content, tools, and feedback strategies. Too much feedback can overwhelm students and teachers while creating a teacher-dependent learning environment. Too little feedback results in confusion, frustration, and feelings of isolation. Having a bank of ready-made feedback resources can streamline the amount of time it takes to get feedback out to students. Developing technical proficiency with a collection of easy-to-use and easy-to-access feedback tools ensures that instructors and students can prepare and deliver feedback quickly, thus being able to increase the amount of feedback over time.

Structuring the amount of information, or length of a feedback message, depends on the topic, progression of skill, and the student’s needs. Keeping messages shorter will help focus on specific content. Extending the message will provide time for supporting details to be included. Selecting two or three key points (e.g. two stars and a wish; stars & stairs) or connecting to important learning goals will minimize a rambling feedback message or a missed ‘teachable moment.’

Humanizing feedback with strategic timing is dependent on keeping the learning objectives and the needs of the learner in mind. Teachers need to be pro-active and responsive when providing feedback during the ebb and flow of the online course. Early into a course schedule, feedback can be more generic, whole-group focused, with targeted individual feedback to students experiencing difficulty getting acclimatized to course content or processes. Later in the course, peer feedback can support engagement and learning while instructor feedback focuses on assignments and prompt redirection or replies to misunderstandings. Good timing is mindful of the learning targets, course schedule, and an instructor’s workload and student requests. Humanize the timing of feedback by prioritizing students who may need cognitive cueing, have become disengaged, or show little interaction with others.

Instructors will make decisions about when to create and share feedback with individuals, small groups, or the whole class. Decisions about audience can be made in the design phase and during the delivery of the course. The audience will determine whether feedback can be public or should be private. Preparing generic feedback for known issues or general course information can be embedded and released where and when needed. When global issues or misunderstandings are noticed, teachers can provide a quick audio or video response to redirect the whole group. When a group of students demonstrates confusion with a topic, the feedback can be targeted to just those who need clarification, using individual emails with a common video feedback message attached. Likewise, group feedback can also be conducted using a Google Hangout where screen sharing and recording the session are options. Individual feedback can be provided in synchronous conversations using Skype or asynchronous recorded, personal messages using a range of available tools.

Feedback for one or by one person can be time-consuming in online learning environments. Instructors should harness the power of collaboration by using peer review since “producing feedback is cognitively more demanding than receiving it, as it involves higher levels of reflection and engagement” (Nicol, 2011). Self-regulation is enhanced when students are actively engaged in establishing and reflecting on the criteria and standards of learning tasks by producing and receiving feedback. Co-creating task rubrics within a shared digital document such as a Google spreadsheet, done synchronously using a chat box to exchange ideas or asynchronously, can increase the human connections between and among students and teachers.

Feedback can be shared with graphics/images, or in written, audio or video recorded formats. The integration of multiple modes can increase the clarity of the feedback message. Decisions about which mode to apply to feedback will depend on student’s needs, opportunity, timing or the availability and affordances of the tools. Use a quick text response if the feedback is simple, straightforward or acknowledges a deeper issue requiring further discussion. As a first choice, apply synchronous audio or video tools to engage in conversations, since a brief online chat can clarify and redirect, and ensure the message is heard. Move to asynchronous feedback if timing or tool affordances complicate communication. Make sure to follow-up once the message has been distributed. Use a sliding scale to differentiate and decide the most appropriate mode to apply to a particular situation, while keeping the human face of the learner in mind.

Create, Distribute, and Monitor

Select one or two audio and video tools that fit your style and personality, but don’t limit your creativity. Explore and blend tools to improve your feedback production. Distribute the feedback in ways that honours the individual, is respectful of their learning style, and leaves them with a clear understanding of what to do next. Make the feedback private and personal. Ensure students are aware when publicly displaying feedback in a forum that is shared, collaborative, and public. In open, public spaces, remember who will potentially see the feedback message and craft it carefully. Monitor responses to feedback diligently so students know you care about their learning. A quick feedback message like ‘Any questions’ or ‘Glad you got it’ will ensure students know you follow-up. Tracking feedback can be done by using tags or searching for key words.

Sequence

Managing to humanize audio and video instructional feedback is possible when there is an effective process applied. Keeping this process in mind, as responses and tasks are presented, will streamline decision-making. Steps in this process are interchangeable and can be applied in any sequence.

- Begin with active and faithful listening. Active listening involves paying attention while suspending judgement. This includes an open and respectful mindset, seeking to empathize and understand, acknowledging bias and differing perspectives while slowing the pace and being comfortable with reflective silence (Hoppe, 2006, p. 8-14). When providing feedback on student work, apply faithful listening. Sircy (2015) states that employing faithful listening “promotes fidelity to our students and their work and encourages us to read more truthfully and generously.” The practice of faithful listening, according to Sircy (2015), forces an instructor to focus attention on the individual as well as the words, thus paying attention to the content and opening up connections. Active and faithful listening to text-based responses becomes possible when using text-to-speech tools, (e.g. TextAloud). Listening to audio and video feedback models best practice in faithful listening.

- Barnes (2015) outlines a formulaic sequence (SE2R) that aids instructors in removing subjectivity and improving consistency in the creation of feedback responses. Begin with a summary of what is seen or has been accomplished. Then explain by identifying skills or concepts that are evident in the work. A subjective tone is achieved when the explanation ties directly to the established guidelines or learning targets. Redirect the student to review or revisit skills, concepts or models that may result in improvements. Resubmission after revision can be recommended within a set of agreed-upon parameters and timelines.

- Effective feedback helps students make connections. Instructors can often see and identify big-picture connections that may not be evident to students unless they are explicitly identified. Connections from text-to-text, text-to-world, text-to-others, text-to-self can add valuable insights when provided in a feedback message. These connections can be integrated into the SE2R sequence or be created as stand-alone text, or an audio or video message, depending on student needs.

- Creating feedback messages in audio and video formats necessitates instructors to think like a reporter and director. Creating media based feedback involves preparing a script, setting up a recording session, checking and revising the message, then uploading and sharing the production. This can be time-consuming and onerous when first starting out, but the process becomes faster with experience. Scripting can be as simple as bullet points that need to be included. Setting up a private and permanent recording space saves time and improves consistency in the messages. Reviewing ‘through the eyes of the student’ and re-doing messages is critical to ensure that tone and valence are projected as intended. Uploading and releasing audio/video files in a batch ensures that all students receive feedback simultaneously, thus decreasing anxiety, questions, or comparisons.

- Track audio/video feedback and remind students to return to feedback as needed. Students will see the value in feedback when they know that instructors monitor and track-back to feedback messages. Keep a record or utilize the affordances of the learning management system (LMS) to help you, as the instructor, to remember where, when and what was shared in feedback messages. Apply tags or keywords to audio and video files to assist in tracking and finding messages.

Figure 2.0 – Sequence text wrap around

The sequence of providing feedback within the schedule of an online course change over time. Being explicit about the process, content, strategies, and tools in the early stages of the course will help students understand feedback decisions and fully engage in the feedback process.

Tools

Affordances and opportunities of tools to capture instructor voice and images that support feedback are varied and numerous. Selecting tools to suit the purpose or to enhance the learning are essential. Knowing where and when to apply tools becomes easier when considering the content, strategy, and sequence of the feedback to be shared. Having a variety of tools increases the potential that feedback is attended to, understood, and applied. Since many online courses are offered within an LMS, the tools within the specific LMS can be applied. Additional web 2.0 tools can add interest, depth, and clarity to the feedback.

Instructor presence can be playful when using comic creators, avatar images (graphic representations to ‘stand-in’ for the speaker) or humour. Online images can be created using Canva, or edited using Pho.to. Comic creators such as Bitstrips, Toontastic or Pixton can provide feedback that is both focused and interesting. Limitations in content, style, tone, and detail can hinder the effectiveness of using these types of graphic and textual feedback. While these creative feedback options model and share teacher personality and interests, they can also be misread or misunderstood by the student.

Audio feedback is perceived to be more effective than written feedback since it enhances feelings of involvement, is linked to retention of content, and is perceived by students to originate from a caring teacher (Ice, Curtis, Phillips & Wells, 2007). Audio recordings (podcasts) provide a human response that varies in intonation, timber, pace, pitch, volume or register of an instructor or participant’s voice (Treasure, 2014). Quicker turnaround and greater detail are advantages to this type of feedback (Macgregor, Spiers & Taylor, 2011). Tools such as Audacity and Garage Band, or mobile device tools such as iTalk, can record an audio clip, embed a static image, and be presented as an mP3 file when uploaded to the LMS or another hosting site such as Soundcloud or AudioBoom. Recordings can capture conversations, thoughts, or insights but can limit understanding without accompanying specificity or detail that visual images can provide. Podcasts can be replayed to ensure that messages are heard, which may improve clarity and understanding of the feedback.

Voice with image productions can enhance the clarity and specificity of the feedback message. Voki, a talking avatar, can provide a less threatening response than one in which the instructor is the talking head. Tellagami uses animation to present the selected summary, explanation, or redirection. These can be created, then linked or downloaded for distribution. While these tools can enhance student interest in receiving the feedback, they can be time-consuming to craft and create. The feedback content and details need to be scripted and recorded, then posted or distributed to the student.

Thompson & Lee (2012) describe screencasts as “digital recordings of the activity on one’s computer screen, accompanied by voiceover narration.” These video recordings can respond to anything produced and submitted in digital format. Feedback on student products or performances can provide focused cognitive cues, redirect misrepresentations in schema or enhance emerging solutions. Screencasting options include Quicktime, Jing, Camtasia, CaptureCast Chrome, or Screencast-O-matic. Deciding to include a ‘talking head’ to the screen-capture, to add personal contact from instructor to student, will depend on the relationship, timing, and student need. This form of feedback is most effective when provided with the draft version of the student’s own work, thus allowing for improvements and changes to be actionable. Final grades can factor in the student response to feedback, thus making the feedback increase in perceived value and effectiveness for both student and instructor.

Integrating text, voice, moving images and video to provide feedback is the most time consuming yet effective method for communicating feedback (Thompson & Lee, 2012; Crook, Mauchline, Maw, Lawson, Drinkwater, Lundqvist, Orsmond, Gomez & Park, 2012, p. 3). Integrating video media enhances the reflective and metacognition components of student learning. Adobe Voice, Animoto, iMovie or MovieMaker or Touchcast can be used to create, produce and project video feedback. The LMS may limit the length or size of the video recording so alternate hosting sites such as YouTube, Vimeo, Dropbox or Google Drive can be utilized to distribute and share these productions. Video feedback engages students in ongoing learning, enhances revisions, and encourages action (Thompson & Lee, 2012). Video feedback can be student produced as a shared or culminating reflection, or an episodic, ongoing video diary (vlog). When integrated into the course design, this feedback is disseminated through informal discussion posts or formal assignment elements. Vlogs can focus on student learning in, on, and of learning events or actions (Smith, 2001, 2011).

Issues

Research indicates that feedback impacts student engagement and learning outcomes (Brookhart, 2008). Feedback, an essential component of teaching presence in a community of inquiry in online spaces, requires time and commitment. Humanizing the process, product and outcomes of feedback are reliant on very human qualities and characteristics. Students are challenged to see the value of feedback, accept descriptive rather than evaluative feedback, and apply feedback to improve learning. Instructors are challenged by decisions around feedback in today’s open and closed digital learning forums. An instructor’s lack of expertise with emerging principles of feedback and of experience with digital tools can hamper feedback production. These issues, while complex and challenging, can be overcome when instructors are working within a community of inquiry. Collaboration by instructors to answer key questions – how best to improve instruction, how to respond to student needs, how to create timely feedback responses, and how to engage students in the feedback process – can shape feedback practices within an online course.

Time

The issue of time is paramount when considering feedback in online learning – the time from the start to end of a course, how long it takes to establish routines and expectations, when tasks are submitted and returned, how long it takes to craft feedback responses using audio and video technologies, and how long the feedback sequence takes. Decisions to humanize feedback mechanisms need to consider the value over time and a return-on-investment since time is a finite commodity. Leveraging the power of peers in the feedback process is one humanizing strategy. Creating anchor samples and pre-recorded feedback messages as part of the course design can help speed up the feedback process and relieve the pressure of time. Instructors who apply a rubric or range of feedback messages can get up-to-speed more quickly. There will never be enough time so careful and frugal decisions about how best to spend time on audio or video feedback need to be made in collaboration between course designers, instructors and students.

Training

Hummel (2006) identifies the need to train instructors in feedback design principles. Instructors who have little experience with the design principles of feedback require information that will inform their practice. Instructors who have little expertise with digital technologies require support when exploring or experimenting with audio and video capture tools and processes. Ongoing training can streamline and encourage teachers to work collaboratively and learn about feedback within a community of inquiry. Presenting best practice tools, strategies and content can increase a teacher’s skills on how to use media-rich feedback to humanize their online presence.

Acceptance

When traditional written feedback is the expectation, student acceptance of audio and video feedback in online learning can be an issue. Being explicit about how media will be applied to feedback is essential. Feed-forward and instructor modelling can set the tone, create space and establish context for feedback (Swing, 2004). Instructional choices in applying best-practice feedback strategies and processes while connecting feedback to grading can increase the perceived value of feedback for students. Instructors can role model their own need for feedback, allowing students frequent opportunities to observe how feedback is integrated into the teaching-learning cycle. Choice and voice in audio or video feedback will further humanize the process, thus ensuring greater acceptance.

Application

Instructors in online spaces find issue when students do not apply feedback to improve their learning outcome despite the time, effort and care taken to create and present feedback. Students can fail to internalize the feedback, make accurate judgements on how to apply feedback or prioritize the feedback to improve learning outcomes (Thomson & Lee, 2012). Feedback strategies and sequences such as those suggested to humanize online instructor feedback might move learning from external regulation by the instructor to internal self-regulation by students.

Open or Closed

At its best feedback is a personal response to a person. Keeping privacy and confidentiality in mind is essential. Being respectful of individual preferences and comfort in open, online spaces are primary considerations. Allowing choice and voice can humanize the feedback experience for instructors and students. Feedback can be provided in open forums, such as comments on a blog, tweeting a response, or within discussion forums in the LMS. Engaging in personal and private audio or video messages within closed and secure digital locations should take precedence when feedback relates to the individual’s performance, particularly when students struggle. Making decisions about when to push from closed to open feedback can challenge an instructor’s comfort level with media messages, i.e., recording themselves in audio or video formats for distribution.

SOLUTION or RECOMMENDATION

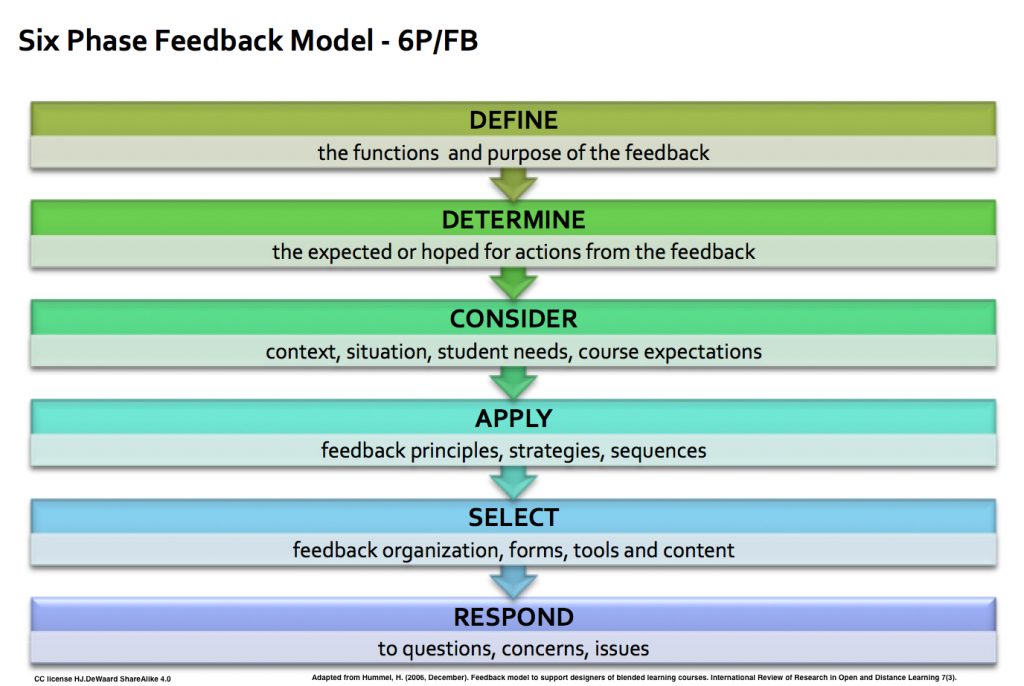

FIGURE 3.0 – Six Phase Feedback Model

Within online learning environments, design decisions about feedback production are part of a complex system that requires a sustainable model. The six-phase feedback model (6P/FB), described by Hummel (2006) can be applied.

When considering the humanization of feedback using audio and video, designers and teachers in the community of inquiry can follow Hummel’s step-down model not only to the overall course design but also to the individual feedback sequences. Although further research into this model is recommended, it is nonetheless a valuable mechanism to guide feedback decisions. Online teachers can humanize their actions when defining, determining, considering, applying, selecting, and responding to feedback questions, content, strategies, needs, mechanisms, and tools.

You can:

- Define the function of the feedback by determining if it will motivate, inform, correct, redirect, or encourage reflection. Decide if the feedback will orient student actions, control behaviours, stimulate thinking, identify errors, isolate reasons for misunderstandings, deliver criteria or provide interventions. Isolating the function of the audio or video message is the first step.

- Determine the potential course of action that the feedback should inspire. Function will influence this schema of possible student responses to the feedback.

- Consider the situational aspects that impact feedback decisions – uniformity, allocation, numbers, timing, orientation, information density and technology (Hummel, 2006). Feedback can be provided to all students simultaneously and uniformly. Computer generated or response dependent releases can be allocated for some feedback, or teachers can decide to provide feedback on-demand as situations arise. The number of students within a course will also help determine what is humanly possible for teachers to provide when using audio or video feedback. Feedback delivery can be predetermined, offered in advance, released ‘just-in-time’ or prepared to respond to student queries. Feedback can be orientated on the process or product, or have a corrective or cognitive orientation. The density of the feedback message is determined by the complexity of the learning process and products. With the multiple audio and video technologies available, teachers need to consider the affordances of selected tools to match the function and potential actions of the feedback.

- Applying principles and guidelines to feedback design is the next phase. These include best practices and decisions on quality, quantity, purpose, content, procedures, criteria, and performance.

- Once the function, action, situation, and guiding principles are determined, the format and organization of the feedback can be designed. Designing the form and function should focus on the needs of the people that will create and receive the feedback.

- The final phase is a reflective response to questions of efficacy and agency of feedback for teachers and students. Considering synchronous vs. asynchronous, personal vs. machine contact, advance vs. ‘just-in-time’, face-to-face vs. recorded, closed LMS or open web, are all valid questions when reflecting on humanizing audio and video feedback.

Applying this design model to feedback in online learning environments can guide teachers in focusing on what the priority is for the human elements of their course delivery.

Research Directions

The desire and trend of incorporating audio and video feedback into online learning environments are growing. Scaling this trend to ensure sustainability is critical. Humanizing the process, strategies and application of feedback will ensure that teachers continue to create effective and engaging feedback messages. Current trends include the creation of feed-forward video, such as teacher created weekly video updates to look back and look forward, to summarize and highlight interactions and information of importance.

Research into measuring student use of instructor created multimedia feedback and its perceived value is growing. The impact of how subjective factors in the creation of audio and video feedback impact student learning and engagement require further investigation (Mandernach, 2009). Research into how different media used to give feedback will impact the purpose of feedback (corrective, informational, motivational, promote reflection) and will improve the instructor’s decisions about where and how to apply audio and video feedback (Middleton, 2010). Ongoing investigations into how teachers’ decisions about content, process and tools for audio and video impact their teaching presence will continue to mold the process of humanizing online instruction.

Conclusion

Humanizing teacher feedback with audio and video content is a complex problem requiring a systems view. Models for managing and prioritizing humanization within digital learning spaces will continue to evolve. While mechanization and computer control in online learning environments are increasingly designed into learning and teaching pathways, the application of audio and video feedback will return the focus onto human to human interactions in these digital spaces. Presenting a human face to feedback content, strategies, and sequences will continue. Increased availability and improved affordances of production tools will support the development of teacher expertise. As a teacher in online learning spaces, it is an exciting time to focus on the human face and voice in feedback messages.

References

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, R., Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 5(2).

Barnes, M. (2015). Assessment 3.0: Throw out your grade book and inspire learning. Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin, A Sage Company.

Brookhart, S. (2008). How to give effective feedback to your students. Alexandria, Virginia: ASCD.

Canadian Initiative for Distance Education Research – CIDER. (2015, June 3). CoI Classroom and Institutional Leadership. [webinar]

Crook, A., Mauchline, A., Maw, S., Lawson, C., Drinkwater, R., Lundqvist, K., Orsmond, P., et al. (2012). The use of video technology for providing feedback to students: Can it enhance the feedback experience for staff and students? Computers & Education, 58(1), 386–396.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105.

Garrison, R., Cleveland-Innes, M. & Vaugh, N. (n.d.) The community of inquiry: Welcome https://coi.athabascau.ca/

Garrison, R., Cleveland-Innes, M. & Vaugh, N. (n.d.) Description: Teaching presence https://coi.athabascau.ca/coi-model/description-teaching-presence/

Hoppe, M. (2006). Active listening: Improve your ability to listen and lead. Greensboro, North Carolina: Center for Creative Leadership.

Hummel, H. (2006) Feedback Model to Support Designers of Blended- Learning Courses. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 7(3).

Ice, P., Curtis, R., Phillips, P. & Wells, J. (2007). Using Asynchronous Audio Feedback to Enhance Teaching Presence and Students’ Sense of Community. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(2), 3-25.

Macgregor, G., Spiers, A. and Taylor, C. (2011). Exploratory evaluation of audio email technology in formative assessment feedback. Research in Learning Technology, 19(1), 39-59.

Mandernach, B.J. (2009, June). Effect of instructor-personalized multimedia in the online classroom. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10(3).

Middleton, A. (2010, October 27). Designing media-enhanced feedback. Paper presented at Audio Feedback Design workshop. JISC.

Nicol, D. (2011, December). Developing students’ ability to construct feedback.

Sircy, J. (2015, January 13). Faithful Listening. Hybrid Pedagogy http://www.hybridpedagogy.com/journal/faithful-listening/

Smith, M. K. (2001, 2011). ‘Donald Schön: learning, reflection and change’, the encyclopedia of informal education.

Swing, R. (2004, June). Understanding the “economies of feedback”: Balancing supply and demand. Brevard College: Enhancement Themes.

Thompson, R. & Lee, M. (2012). Talking with students through screencasting: Experiments with video feedback to improve student learning. The Journal of Interactive Technology & Pedagogy, 1.

Tomlinson, C.A. & Moon, T. (2013). Assessment and student success in a differentiated classroom. Alexandria, Virginia: ASCD.

Treasure, J. (2014, June 27). How to speak so that people want to listen https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eIho2S0ZahI

Additional Readings

Akyol, Z. & Garrison, D.R. (2008, April). Community of Inquiry: The Role of Time. Presentation at the First International Conference of the new Canadian Network for Innovation in Education (CNIE), Banff.

Australian Society for Evidence-Based Teaching (n.d.) How to give feedback to students: The advanced guide. Pinnacle.

The Australian Society for Evidence Based Teaching (n.d.) 8 Strategies Robert Marzano & John Hattie Agree On.

Bergström, P. (2010, May) Process-Based Assessment for Professional Learning in Higher Education: Perspectives on the Student-Teacher Relationship International Review of Research in Open and Distance 11(2).

Canadian Initiative for Distance Education Research -CIDER. Webinars http://cider.athabascau.ca/sessions

Garrison, D. R. (2016). Thinking Collaboratively: Learning in a Community of Inquiry. London: Routledge.

Garrison, R., Cleveland-Innes, M. & Vaugh, N. (n.d.) The community of inquiry: Publications. https://coi.athabascau.ca/publications/

Hattie, J. & Timberley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112.

Hawkseye, M. (n.d.) The Musings of Martin Hawkseye – Student Audio Feedback: What, why and how. [blog post]. https://mashe.hawksey.info/2009/05/student-audio-feedback-what-why-and-how/

Higgins, R., Hartley, P. & Skelton, A. (2001). Getting the message across: The problem of communicating assessment feedback. Teaching in Higher Education, 6, 269-274

Middleton, A. (2010, October 27). Media-enhanced feedback case studies and methods. JISC.

Nicol, D.J. & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199-218.

Reading University. (n.d.) Using video for feedback provision. [website] http://www.reading.ac.uk/videofeedback/

Swann, J. (2010). A Dialogic Approach to Online Facilitation. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(1), 50-62.

Van Schie, J. (n.d.) Concept Map of Community of Inquiry http://cde.athabascau.ca/coi_site/documents/concept-map.pdf

Vaughan, N. (2013). Community of Inquiry Framework, Digital Technologies, and Student Assessment in Higher Education. In Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. R. (2013). Educational Communities of Inquiry: Theoretical Framework, Research and Practice. pp.1-347.

Key Terms sand Definitions

Affordance refers to the relationship between an object, item, environment and an individual’s behaviour. The object, item or environment has a perceived and a real action within its structure or design. An individual’s response to the perceived or real action that is enabled is dependent on specific factors such as experience, cultural context, or beliefs.

Agency relates to the ability, potential, or capacity that any individual has to act within their environment in either an involuntary or purposeful manner. Agency is the control over one’s actions, directions or intentions in a purposeful or goal-directed manner.

Cognitive load is the amount of information an individual can realistically understand or recall within any given learning moment. The more dense or challenging the subject matter, the more limited an individual’s ability to comprehend, distinguish and grasp key details. This ‘load’ of information and an individual’s ability to manage it is dependant on factors such as nutrition, sleep, distractions, or readiness.

Feed forward is the process of providing messages that proactively address, avoid or respond to known or perceived issues, problematic processes, challenging concepts or complex tasks.

Learning management system (LMS) is a computerized software tool designed to document, track, deliver, store and report on content and actions by course instructors and participants. It is a secure, password-protected space where learning objects and resources are presented in a set sequence over a scheduled time.

Multimodal refers to the integration of multiple modes of communicating messages through text, colour, sound, image, transitions or moving image.

Screen capture is a snapshot or still image of items displayed on a computer screen. This can be the whole screen or selective parts of the screen. This image can be annotated or enhanced using software (e.g. Skitch) to further elaborate on what is seen, not seen, directions for further action or suggested changes.

Screencast is a recording of a computer screen, actions or movement on the screen, images recorded from a screen along with a voiced narration or music accompaniment.

Self-regulation is the ability of an individual to manage and set his or her own actions within a complex, interconnected sequence. It involves the capacity to control impulses, start purposeful action, and manage competing alternatives. Both social-emotional and cognitive domains are engaged in self-regulation. In the universal design for learning framework, self-regulation falls within the area of executive function.