5 Using Video to Humanize Online Instruction

The application and integration of video into the community of inquiry (CoI) framework can humanize instructor, social and cognitive presence for effective online learning. The concept of affordances and universal design for learning principles can be applied to design decisions when video is applied to support the CoI model. Knowing that video includes a variety of formats and options beyond the lecture-capture model is essential. Understanding a pedagogy of video – code breaking, meaning making, using, applying, and identifying persona – will ensure that video assets support critical and digital learning outcomes. Design with video can activate deeper reflective practice when applying location, integration, creation, annotation, collaboration, and curation of video assets. Issues when considering video integration into online learning spaces include quality/quantity, open/closed, actor/teacher, asynchronous/synchronous, or live/recorded video. Awareness of universal design for learning principles and ensuring that video is accessible to all students is an additional issue. Research into the efficacy and constraints of video to humanize online presence is critical to enhance learning outcomes in online spaces.

Introduction

“Knowledge comes by taking things apart: analysis.

But wisdom comes by putting things together.”

John A Morrison

Video technologies provide affordances to humanize instruction within online learning spaces. With the proliferation and ubiquity of developed and emerging video tools, instructors can humanize voice and choice within a learning community of inquiry (Fulwiler & Middleton, 2012). Social presence, teaching presence, and cognitive presence is impacted by the strategic use of video. Presence is enhanced when integrating the creation, curation, and annotation of video into the discourse, climate and content of online learning spaces. Design considerations include the affordances of video tools and techniques, the application of universal design guidelines, and the definition of video parameters. While text is a dominant mode of engagement in online courses, video is becoming more prevalent as emerging technologies are adapted to online learning spaces. Applying best practice, expertise, affordances, effective design principles, and individual experience to video integration will humanize online learning for students and teachers. Humanizing teaching and learning experiences is the ultimate goal when putting video together with online learning.

Background

Community of Inquiry

The conceptual framework for a community of inquiry, as developed by Garrison, Anderson & Archer (2000), outlines elements and interrelationships that occur in online learning spaces. The key participants, teachers and students, interact within social, cognitive, and instructor presences that determine the value and depth of the educational experiences. The design and selection of learning objects and actions determine the effectiveness of content, climate and discourse (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 2000).

The community of inquiry (CoI) framework is applied to humanizing online learning with video. Video can enhance the teacher’s presence when humour, wit, and personable context are applied to the online course subject matter (Hibbert, 2014). Video in online learning can enhance feelings of immediacy and closeness between instructors and students, thus improving social presence. An individual’s personality can be projected through video recorded messages, conversations or discussions (Griffiths & Graham, 2009). Both live video conferencing and recorded video enhance cognitive presence since viewing and reviewing the educational content are in the hands of the instructor and student.

Affordances

Video and multimedia provide affordances not available to text or audio information. These affordances can enhance relationships between instructors and students while focussing on designed artefacts (Kannengiesser & Gero, 2012). Norman (2013) describes affordances as constraints, conventions, signifiers, and opportunities. These can be applied to video production and application. In online learning environments affordances can be conceptual or physical (Norman, 2013). Affordances range from easy to impossible. Since human input and technological advances change over time, the affordances of video are dynamic and evolving.

Kannengiesser & Gero (2012) outline a structure-behaviour-function framework that shapes video affordances. The structure of video is constrained by the tools used to create, view, or manage these media resources. The function of a video asset shapes its structure thus determining the subsequent behaviour of the viewer/creator. Kannengiesser & Gero (2012) identify how behaviour toward video can involve reflexive, reactive, and reflective responses. Reflexive affordances describe the match between an artefact and a user as experienced through the user’s sensorimotor system. This involves both the physical actions and the internal patterns and schemas, for example, a user’s understanding that a right pointing arrow indicates play or that two lines indicate stop/pause. A reactive affordance, the possible action resulting from/with an artefact, is shaped by time, knowledge, situation and user bias. Reactions to video are both predictable and unpredictable thus impacting the affordances of video tools in online learning. This is exemplified by possible viewer reactions resulting from using a cute cat video that may or may not engages learners’ social or cognitive presence. Reflective affordances occur when there are changes in user expectations that result from different situations (Kannengiesser & Gero, 2012). Exploration and discovery can impact the video affordances for instructors and learners in online spaces. For example, applying collaborative video annotation (situation) leads to changes in the user’s expectations (not so hard after all) that produce different affordances (shared video notes). The affordances of video to humanize online learning are dynamic and evolving, with the potential to improve the social, instructor, and cognitive presence in online learning spaces.

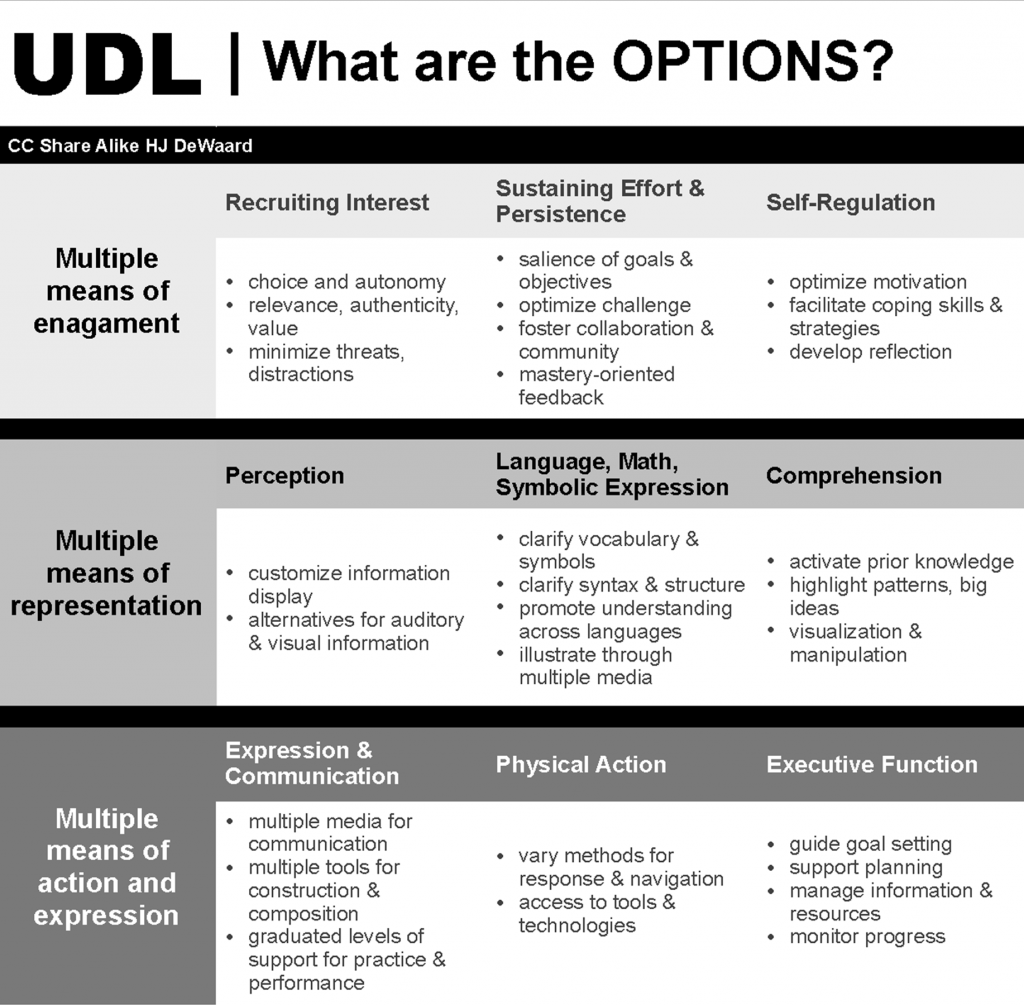

Figure 1.0: Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design for Learning

Applying the principles of universal design for learning (UDL) to the application, production, and distribution of video in online learning environments can enhance humanizing effects and ensure all students meet with success. UDL can provide a framework for an active and integrated approach to using video when based on the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) guidelines. Video can enhance the what (representation), how (action and expression) and why (engagement) of online learning (CAST, 2015). Utilizing video to enhance engagement can focus on self-regulation, persistence, sustained effort, and interests. Engaging learners with multiple means of representation with video will enhance comprehension, provide variety in expression, and accommodate alternative ways of understanding. Designing video experiences into online learning can humanize the options for executive function, expression, communication, and physical action. Purposeful, motivated, resourceful, knowledgeable, strategic, and goal-directed learning is enhanced when applying UDL principles into video implementation within online learning. Video options that apply UDL guidelines complement the elements in the social, cognitive, and teaching domains of the CoI framework.

What counts as Video?

In current online educational contexts, video lecture capture frequently takes priority. Moving beyond this category of video requires an understanding of the forms, types, and purposes for integrating media into teaching and learning. Types of video that can be applied to online learning include interview, talking head, live webcast, video presentation, live demo, screencast, photomontage, promotional, pitch and sizzle, informational, testimonial, animation, or video email (Bortone, n.d.). Video incorporates multiple media (text, graphics, images, icons, sound, voice, transitions, and movies) in dynamic interactions. Integrating brief image and video production tools, such as a Vine®, GIF or meme, can be incorporated or ‘smashed’ into longer episodes. Video includes conversations or conversational content. Video has moved beyond the traditional ‘talking head’ presenting knowledge or wisdom.

Towards a Pedagogy for Video

Video is becoming ever more prevalent and accessible within online learning environments (Bonk, 2008). Humanizing the integration of video requires the application of critical digital pedagogies in order to locate, integrate, create, annotate, collaborate, and curate video resources. Exploring tools and applying production tips can enhance persona and humanize the process and products of learning.

Learning and instruction within online spaces are shifting toward the incorporation of critical digital pedagogies. A critical digital framework has implications for academic engagement and curriculum delivery (Hinrichsen & Coombs, 2013). According to Hinrichsen & Coombs (2013) successful learners engage in:

- code-breaking through deciphering and producing by understanding navigation, conventions, operations, stylistics, and modalities

- using through consuming and producing by finding, applying, problem-solving, and creating multi-modal resources

- analyzing to become a perceptive practitioner by deconstructing, selecting and interrogating digital and media resources

- making meaning through reading, relating and expressing through multi-modal text participation

- identifying persona by showing sensitivity to representation, identity and membership through identity building, managing reputation, and participation.

When considering the place for video in learning and instruction, this is a useful framework to analyze social, teacher, and cognitive presence.

Locate – Finding, analyzing, and using quality video for online course content can be time-consuming and confusing. Students and instructors can apply search parameters to university and publisher collections, user-created open community collections, publicly funded and organizational collections (museums, libraries), and shared video repository sites (Vimeo®, YouTube®). Focusing on variety, engagement, and topic content within the search framework will guide the video selections. Some location options include:

- Canadian National Film Board

- Library of Congress

- Moving Image Archive

- Edudemic’s 100 best video sites for educators

- RefSeek’s guide to the 25 best online resources for free educational videos

Open searches can result in serendipitous outcomes. Sometimes the most unlikely clip will complement or connect to course content in unusual ways, which can further humanize the application of video. Quirky, humorous, or diverse video content can engage, catch students’ attention, create cognitive dissonance, or build understanding.

Integrate – Deciphering, deconstructing, and interrogating video will facilitate problem-solving. Decisions about integrating where, when, and how these video assets will be shared or released can humanize the course experience. Integrating UDL with video, by applying close captioning, models sensitivity to marginalized learners. Technology, such as mail video with MailVU® or Eyejot®, can extend integration options. Bonk (2008) outlines pedagogical applications and integration strategies when using video, such as an advanced organizer to start a topic, ending a class or topic, to start or end a discussion, as a preview with questions before a class or discussion, as an in-class task with discussion prompts, for pause & reflection, as a focused prompt to highlight key concepts, embedded within a course quiz or test, on-demand based on class activity or discussion, and as a video-conferencing recording to foster interactions across locations (Bonk, 2008). Careful integration of video to match or complement the course topics can be challenging.

Create – Video creation involves meaning, making, and code breaking. When creating video instructors or students attend to the purpose, content (including mashups and remix), format, process, strategies, and tools. Identifying the purpose for the video production is a first and necessary step. The purpose will then dictate the content. Video can be used to instruct, set a tone, model expectations, examine detail, or provide feedback. The content can be general, specific, humourous, provide a metaphor or analogy for a topic, add insight, or summarize. Instructor created video formats can extend beyond a lecture-capture composition into Pecha Kucha®, Ignite® or TED-talk® formats. Creative application of text features, typography, still or animated images including memes or gifs, comics, and green-screen can add interest and engagement to videos. Bonk (2008) outlines pedagogical applications for student-created video – interviews, debates, sharing and rating, recognition by peers and instructor, illustrating course concepts, explanation of connection to course topics, collaborative anchoring, and creating video collections. A video creation process includes decisions on content, context, objectives, resources (equipment, time, costs), and format. Creating video can be done individually or within a media team that includes the instructor. The process includes a linear progression – pre-production (scripting, storyboarding), production (collecting, filming, editing), and post-production (reviewing, releasing). Fulwiler & Middleton (2012) suggest that new media creation is a non-linear compositing and new recursivity process that includes analytic and cognitive explorations that require time and attention. Tips for video recording, when creating instructor videos, include checking the background, incorporate movement strategically, face the camera, limit external sounds, light from in front and beside, use a good microphone, pace yourself, and prepare a script or sequence. See more about these tips in Table 1 at the end of this chapter.

Composing cool or edgy video requires an awareness of strategies within traditional and new rules for media production (Fadde & Sullivan, 2011). Fadde & Sullivan (2011) elaborate on traditional techniques for framing, shot distance, jump cuts, ethos, lighting, background and views. Instructors can experiment with emerging strategies such as stark lighting, extreme close-ups, and unusual backgrounds. Trends in vertical video will impact the ease of creation and access when using mobile technologies (Schlenker, 2015). Some instructors have explored the use of walk-and-talk video (Kuropatwa, 2014).

When scripting and crafting the video consider web design elements – mood boards can help you establish a tone or focus based on colour palette, typography, graphic style, iconography, navigation style, spatial awareness, and overall contrast (Cao, 2015).

Selecting and applying video tools will be determined by available technologies, budgets, and user/creator expertise. Affordances and signifiers of apps and software tools for video production need to be carefully considered prior to their application.

Annotate – Using annotation tools when video is incorporated into course content can enhance cognitive engagement. Using video collection repositories such as YouTube and Vimeo can allow students and instructors to make notes to coincide with video content. By integrating emerging tools such as Videonot.es (a Google Extension) or Vialogues (a discussion platform), instructors and students can engage in collaborative, synchronous or asynchronous conversations about the messages within a video asset. Affordances of video annotation and collaboration tools should be considered for UDL principles and issues of accessibility.

Collaborate – Critical digital pedagogical skills integrated into collaboration with video include identity building, managing reputation, modeling sensitivity to membership in a community of inquiry, as well as relating and expressing through participation. Technology, such as Synchtube allow participants to synchronously view and chat about the same video. The instructor can cue or jump to specific time markers in the video to ensure students pay attention to key details. Google Hangouts, another synchronous video tool, allow users to hold conversations or group discussions that can be recorded for future reference. These can then be viewed asynchronously and be annotated or close captioned to provide clarity when referencing key ideas or concepts.

Curate – Video curation provides opportunities for students to interrogate digital and media resources by deciphering conventions, stylistics, and modalities. Making decisions about relevance to a particular topic builds skills in analysis and synthesis. Collaborating to create a shared video collection can increase a sense of individual and group identity. Shared video channels, curated by an instructor or design team in YouTube, can provide access to all relevant video assets in a course module to all students in one location. Using social bookmarking tools such as Pinterest, Diigo, Evernote or ScoopIt can provide an ongoing, user defined, collaborative, rich resource library for current and future course participants.

Issues

When considering the humanizing potential of video in online learning spaces, considerations include the quality vs. quantity in the production and distribution of video assets, the use of open repositories or closed LMS systems, and the use of actors vs. teachers to create video resources. Those who use video to humanize online spaces need to balance their application of live, recorded, synchronous, or asynchronous video options; each brings unique issues into the forefront. Issues and consideration of accessibility for video viewing, creation, and production need to ensure that UDL principles apply to all learners, but especially those with learning challenges.

Quality and Quantity

Selective application and balancing the variation in quantity and quality of video assets can ensure a human feel and presence in the learning space. Quality and quantity are not an either/or decision – it is a range that is dependent on affordances of the technologies and the expertise of the participants. An overreliance on video within an online course with an overabundance of video resources can negatively impact the humanizing potential that video affords within online communities of learning. A surplus of information within a video sequence can impact information retention and increase cognitive load (Beauregard, Rousseau & Mustafa, 2015). Managing the quantity of content specific detail within a video asset is essential. Professionally prepared videos can help avoid technical issues, improve the quality of the production, and enhance viewer engagement (Beauregard et al., 2015). Quality standards, as applied within an online course quality management framework, may dictate the variety of video options available to instructors and course designers.

Open and Closed

The integration of open educational resources (OER) is expanding in many learning spaces. The shift to OER is supported in many countries as a response to growing demands for quality video in online learning. Remixing, adapting, and reusing video resources are enabled through OERs. By using Creative Commons licensed or self-produced video, the available range of open and accessible video resources is expanding. The decision to manage video libraries as openly accessible repositories or warehousing video within a closed LMS system is a challenging one. Video that includes images of individuals requires deeper levels of decision-making since permission, safety, and security of instructors and learners should be a primary consideration. Decisions about sharing or going public with personal video content should be made by those included in the video.

Actor and Teacher

With increased demands on instructor time and decreasing budgets for online learning, a trend to supplant actors for instructors in video production have been noted. Videos including actors in lieu of instructors can have a more professional look and feel. A video asset with topic-specific content can be produced using a well-written script scenario and a recording team. Student engagement increases with the use of instructor produced video sequences (Mandernach, 2009). When an instructor faces the camera and records a video, they can improve the emotional connections to students resulting from facial expression and movement (Borup, West & Graham, 2012).

Live and Recorded, Synchronous and Asynchronous

Video options are dependent on time and space within an online course offering. A short course schedule will limit the time that can be spent on live, synchronous video. Some teacher-recorded video can be created prior to a course opening, when instructors may have time, but these may not respond directly to student needs. Live video options can be challenging to coordinate and be subject to technical issues (Griffiths & Graham, 2009), but can increase social connection and a sense of identity within the group. Recording live video sessions can improve communication, understanding, and insights when participants refer back to what was said. The impact of asynchronous video on the sense of immediacy and social presence requires further study (Griffiths & Graham, 2009).

Managing and creating video takes time and expertise. Fulwiler & Middleton (2012) bring attention to emerging processes to consider when producing video as traditional linearity with a text-based foundation is supplanted by complex compositing and recursivity. New and emerging video technologies can improve affordances for novice or average users, but there is still a learning curve to adopting and applying video to online instruction.

Accessibility

Instructors and learners in online courses bring a range of physical, intellectual and emotional skills and abilities to the learning space. Ensuring that UDL considerations for video are part of the planning and decision-making process is often an issue when time and skills are limited. Moving beyond ensuring that close-captions on video are a consistent standard of practice, faculty in online learning require an awareness of W3C web accessibility standards and guidelines. Since this is not usually provided as in-depth professional development for faculty or instructional designers, issues of access, ease of use, and opportunities to engage can be missed in the design and implementation of video. Some web-based video tools are less accessible to special learners, thus making their inclusion in video activities and assets a greater challenge to learning. When planning the use of video in an effort to humanize online learning spaces, considerations to inclusive practices and ease of access should be taken into account.

Recommendations

To fully humanize video for online learning spaces, it is critical that instructors and course designers collaborate and innovate within interdisciplinary teams that focus on learning, have strategic academic leadership, understand complex organizational challenges, and incorporate experience and technical support (Shilling, 2015). Since faculty development is one of the barriers to adopting video to humanize online learning, a collegial form of shared learning can provide ongoing support for new and returning faculty. By sharing in open dialogue about issues, concerns, success, or best practices in applying video, instructors can minimize the anxiety or time constraints and maximize learning opportunities for their students.

Valenti (2015) presents the notion of the ‘T’ shaped professional – one who’s abilities and competencies cross disciplinary boundaries, who is comfortable within many systems and disciplines while holding deep analytic thinking and problem-solving skills in at least one discipline or system. Course instructors who delve into video applications within a community of inquiry, from whatever their discipline will become a learner and teacher, disciplined in media, teaching and course subject matter. Faculty support is essential when video is integrated into online spaces, particularly with UDL, accessibility and in developing skills with video tools.

Research Directions

Research into the impact of asynchronous vs. synchronous video on the teachers’ and students’ sense of immediacy and social presence requires further study. Since the affordances for video in real-time using tools like Google Hangouts moves into the ‘possible,’ instructors will turn to this or similar tools to engage students in connected learning. Examining how informal, instructor-produced animated or interactive video impacts cognitive and social presence will need further exploration since these types of video creations are not yet commonly used in course instruction. The role of introductory videos created by instructors and students to feelings of inclusion and group cohesion would be of importance when examining social presence within online learning. How video can be applied to transform code breaking and meaning making for students and instructors, with a focus on cognition, dissonance, and retention, will require further inquiry. The increased use of mobile technologies will alter where, when and how video is consumed, created, and applied to learning. Further research into the impact of mobile video technologies will be essential.

Conclusion

Text still predominates in online learning spaces as a primary means of expression and communication, but video is fast becoming a tool to enhance pedagogical outcomes and social engagement. Insight into formats, affordances and UDL principles will further ensure that video integration into online learning humanizes digital spaces and develops the social, cognitive, and instructor presence. Instructors who apply effective pedagogical practices for video to social and cognitive interactions will further humanize their course content and processes. Research into video tools, strategies, and practices will advance learning outcomes in learning communities of inquiry in online spaces.

References

Beauregard, C., Rousseau, C., & Mustafa, S. (2015). The use of video in knowledge transfer of teacher-led psychosocial interventions: Feeling competent to adopt a different role in the classroom. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 41(1)

Bonk, C. (2008, March). YouTube anchors and enders: The use of shared online video content as a macrocontext for learning. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association (AERA) 2008 Annual Meeting.

Bortone, L. (n.d.) 16 Types of videos you can create http://www.magnoliamedianetwork.com/16-types-of-marekting-videos/

Borup, J., West, R. & Graham, C. (2012). Improving online social presence through asynchronous video. Internet and Higher Education, 15, 195-201.

Cao, J. (2015, July 17). Why Mood Boards Matter in the Board Room http://webdesignledger.com/tips/mood-boards-matter-board-room#sthash.P1cBJo6D.Tj9V1xnO.dpbs

Eyejot: video mail in a blink© (2015) http://corp.eyejot.com

Fadde, P. & Sullivan, P. (2011, December 15). Cool and credible web video: Old rules, no rules, or new rules? Educause Quarterly.

Fulwiler, M. & Middleton, K. (2012). After digital storytelling: Video composing in the new media age. Computers and Composition, 29, 39-50

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text‐based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2), 87‐105.

Griffiths, M. & Graham C. (2009). Using asynchronous video in online classes: Results from a pilot study. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 6(3), 65-76.

Hibbert, M. (2014, April 7). What makes an online instructional video compelling? Educause Review.

Hinrichsen, J. & Coombs, A. (2013). The five resources of critical digital literacy: A framework for curriculum integration. Research in Learning Technology, 21.

Kannengiesser, U. & Gero, J. (2012). A process framework of affordances in design. MIT Press Journals, Design Issues, 28(1), 50-62.

Kuroptwa, D. (2014, October 29). While walking…. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLWR3gmxq_cOU_MrfZFthZxodRrtWzr-wk

MailVU©. (2013) http://www.mailvu.com/basic-plan.htm

Mandernach, B.J. (2009). Effect of instructor-personalized multimedia in the online classroom. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10(3).

National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2014, November 12). Universal design for learning guidelines.

Norman, D. A. (2013). The design of everyday things: Revised and expanded. New York: Basic Books. London: MIT Press (UK edition).

Norman, D. A. (n.d.) Affordances and design. JND.org http://www.jnd.org/dn.mss/affordances_and.html

Schlenker, B. (2015, June 5). Effective use of vertical video for training. [Blog post] http://www.litmos.com/blog/video/effective-use-of-vertical-video-for-training

Shilling, P. (2015, May 11). Carving a role for academic innovation. Educause Review

Valenti, M. (2015, June 22). Beyond active learning: Transformation of the learning space. Educause Review.

Vanderheiden, G., Reid, L.G., Caldwell, B., & Henry, S.L. (Editors). (2014, September 16). In W3C® Web Accessibility Initiative (How to meet WCAG 2.0).

Additional Readings

Berkun, S. (n.d.). Why and how to give an ignite talk. http://www.ignitetalks.io/videos/why-and-how-to-give-an-ignite-talk

Borup, J., Graham, C.R., & Velasquez, A. (2011). The use of asynchronous video communication to improve instructor immediacy and social presence in a blended learning environment. In A. Kitchenham (Ed.), Blended learning across disciplines: Models for implementation. (pp. 38-57). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Brown University (n.d.) Online tutorials for online course design. https://brownonline.zendesk.com/hc/en-us

Dunn, J. (2012, Aug 10). The 100 best video sites for educators. http://www.edudemic.com/best-video-sites-for-teachers/

Delen, E., Liew, J., & Willson, V. (2014). Effects of interactivity and instructional scaffolding on learning: Self-regulation in online video-based environments. Computers and education, 78, 312-320.

Henry, J. & Meadows, J. (2008). An absolutely riveting online course: Nine principles for excellence in web-based teaching. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 34(1).

Kent State University, Online Learning Team, Office of Continuing & Distance Education. (n.d.) How to create instructor and course introduction videos.

Maniar, N., Bennett, E., Hand, S., & Allan, G. (2008). The effect of mobile phone screen size on video-based learning. Journal of Software, 3(4), 51-61.

McGreal, R. (2015). Where to find quality open educational resources. https://vimeo.com/91121098

Merkt, M., & Schwan, S. (2014). Training the use of interactive videos: effects on mastering different tasks. Instructional Science, 42, 421-441.

Merkt, M., Weigand, S., Heier, A., & Schwan, S. (2011). Learning with videos vs. learning with print: the role of interactive features. Learning and Instruction, 21(6), 687-704.

PechaKucha. (n.d.). Frequently asked questions: What is Pecha Kucha? http://www.pechakucha.org/

Sibley, K. & Whitaker, R. (2015, March 16). Engaging faculty in online education. Educause Review.

Shephard, K. (2003). Questioning, promoting and evaluating the use of streaming video to support student learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 34(3), 295-308.

Sherer, P. & Shea, T. (2011). Using online video to support student learning and engagement. College Teaching, 29(2), 56-59.

TEDx. (n.d.). How to give a TED talk. http://storage.ted.com/tedx/manuals/tedx_speaker_guide.pdf

Wieling, M. B., & Hofman, W. H. A. (2010). The impact of online video lecture recordings and automated feedback of student performance. Computers & Education, 54(4), 992-998.

Zhang, D., Zhou, L., Briggs, R., & Nunamker Jr, J. (2006). Instructional video in e-learning: Assessing the impact of interactive video on learning effectiveness. Information & Management, 43(1), 15-27.

Links and Resources

- Canadian National Film Board https://www.nfb.ca/explore-all-films/

- Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/film-and-videos/collections/

- Moving Image Archive https://archive.org/details/movies

- Edudemic’s 100 best video sites for educators http://www.edudemic.com/best-video-sites-for-teachers/

- RefSeek’s guide to the 25 best online resources for free educational videos http://www.refseek.com/directory/educational_videos.html

Keywords and Definitions

- Animation – video created using images, comics, avatars, moving text, moving transitions, with embedded voice and/or music. This is not the same as a cartoon style show presented on television, rather it is crafted using multiple modes of communicating a message. Animation refers to the movement of items on the screen that enhance or highlight key components of the video message.

- App-Smashing refers to the integration of several applications found on tablet devices. Several apps are selected and used to create specific components of a video based on their affordances. These smaller, specific messages are then ‘smashed’ together to suit the content, purpose, mode, and strategies.

- GIF, or graphics interchange format is a file format for both animated and static images. GIFs are compressed image files that reduce transfer and upload time. Animated GIFs have moving parts that attract attention.

- Mashup – is a compilation video that selectively applies portions of videos available on the web to create a new or unique video asset. A mashup is a mix or remixing of content or re-purposing material to create a different message.

- Meme – is a humourous image, message, text, created and spread rapidly over the internet. Variations of a message or remixing parts of the original message are done to extend the duration or spreadability of a meme.

- Multimodal – refers to the integration of multiple modes of communicating messages through text, colour, sound, image, transitions, or a moving image.

- Open educational resources – the United Nations describes OER as any variety of educational resources that are in the public domain, offered freely for redistribution, or created using an open license such as a Creative Commons license. Materials that are OER can be freely and legally used, adapted, and re-shared without concerns of copyright infringement.

- Pedagogy – is the integration of teaching, thinking and the actions or practices of educators or the craft of teaching.

- Screencast – is a recording of a computer screen, actions or movement on the screen, images recorded from a screen along with a voiced narration or music accompaniment.

- Social bookmarking – is a way for individuals or groups to store, organize, label, or search for web pages. These sites of interest can be managed and collected using web-based software that helps users connect, collect, and curate internet resources.

- Talking head – is a video format that captures an individual in a close-up, facing the camera position while they talk about a particular topic or issue. This talking head can take prominence by being centered or the image can be offset to one corner of the screen to allow for another image or video to take priority.