Chapter 4: Hemostasis

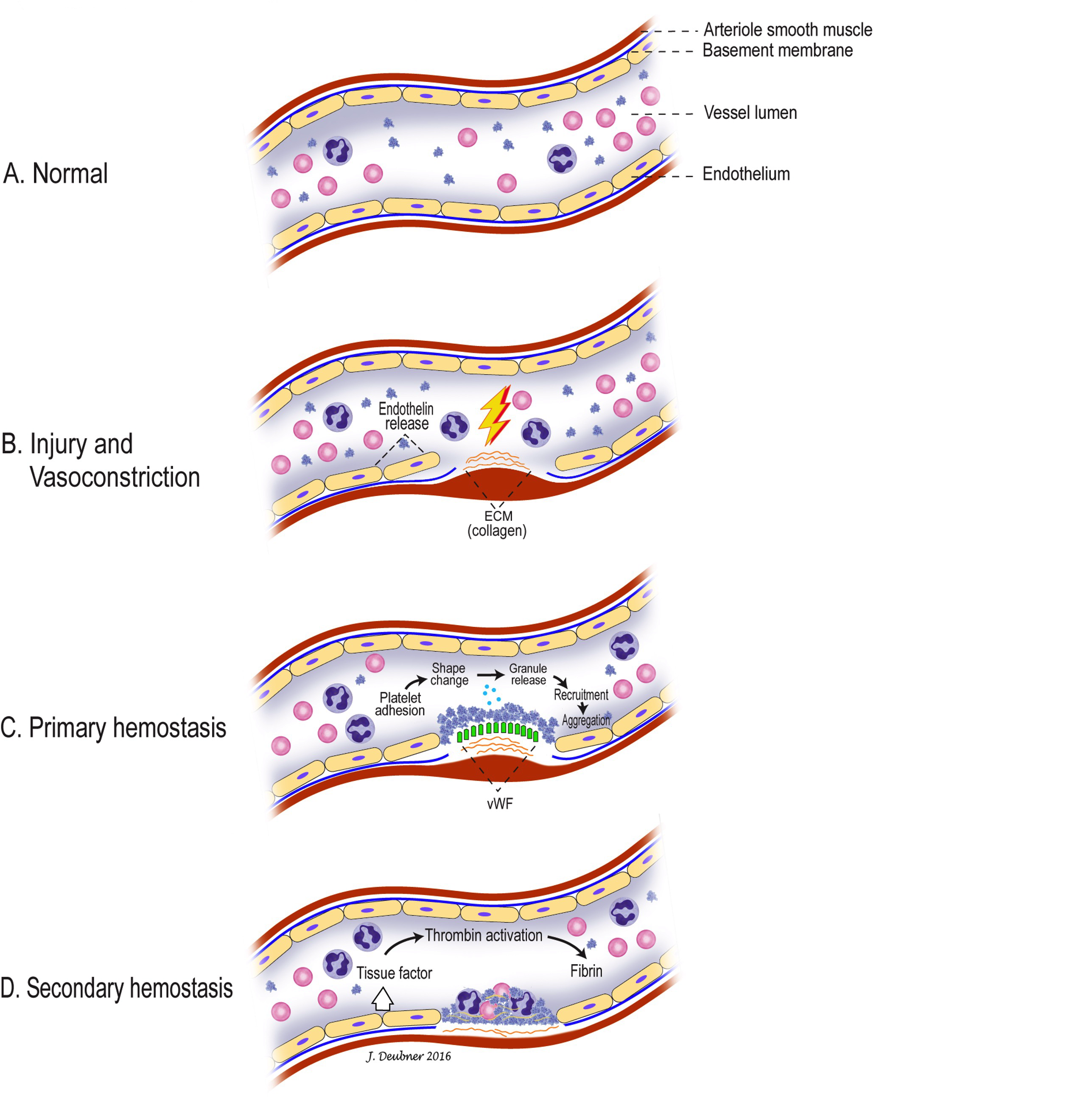

Hemostasis is the complex interaction of proteins, cells, and blood vessels with a goal of arresting hemorrhage. Blood clot formation occurs at the site of vascular injury and this must occur quickly, remain localized, and be tightly controlled. With an imbalance or dysfunction at any level of the hemostatic process, excessive bleeding or clotting may occur, both of which can be life-threatening. In health, a balance is maintained so that animals experience neither hemorrhaging nor thrombosis through hypocoagulation or hypercoagulation, respectively. This balance is maintained in several ways: intact blood vessel endothelium is anticoagulant, whereas, injured endothelium is procoagulant; many of the coagulation factors must be first activated in order to participate in clotting; and potent anticoagulants are present both in the peripheral blood and bound to vascular endothelium. The normal sequence of events when vascular injury occurs is: vasoconstriction, platelet plug formation, and coagulation, followed by clot retraction and fibrinolysis (Figs 4.1 and 4.6). There is clinical relevance in distinguishing between primary hemostasis (vasoconstriction and platelet plug formation) and secondary hemostasis (coagulation), although both are closely associated and often occur simultaneously, depending on the degree of injury.

Complex interaction of proteins, cells, and blood vessels to arrest hemorrhage - a highly regulated, finely balanced process.

See Secondary hemostasis.

Specialized layer of cells lining the blood vessels.

Any of several plasma components essential for secondary hemostasis.

An anucleate (in mammalian species) cytoplasmic fragment arising from a megakaryocyte; vital for primary hemostasis.

Process in which fibrin is broken down, resulting in clot dissolution.

Initial events in hemostasis, comprising vasospasm/vasoconstriction and platelet plug formation.

Results in formation of cross-linked fibrin to stabilize the platelet plug.