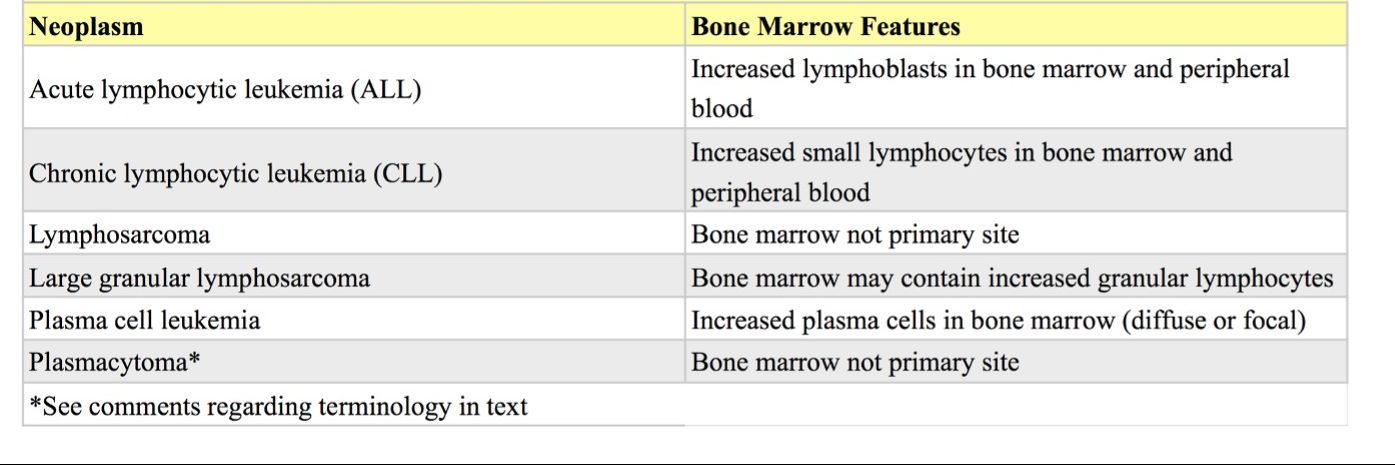

Lymphoid Neoplasms

Lymphoid tumors represent the most common hemopoietic neoplasm of domestic animals (Table 3.1). Solid lymphoid tumors, more correctly called lymphosarcoma (LSA), but often referred to as lymphoma, may occur with or without bone marrow involvement. When solid tumors and lymphocytic leukemia are identified simultaneously, it may not be possible to determine where the neoplasm originated. Lymphoid neoplasms may be classified according to: anatomic location; cytologic features; cytochemical features; histologic features; immunohistochemical features; and other molecular characteristics. This section will focus on lymphoid neoplasia involving the bone marrow.

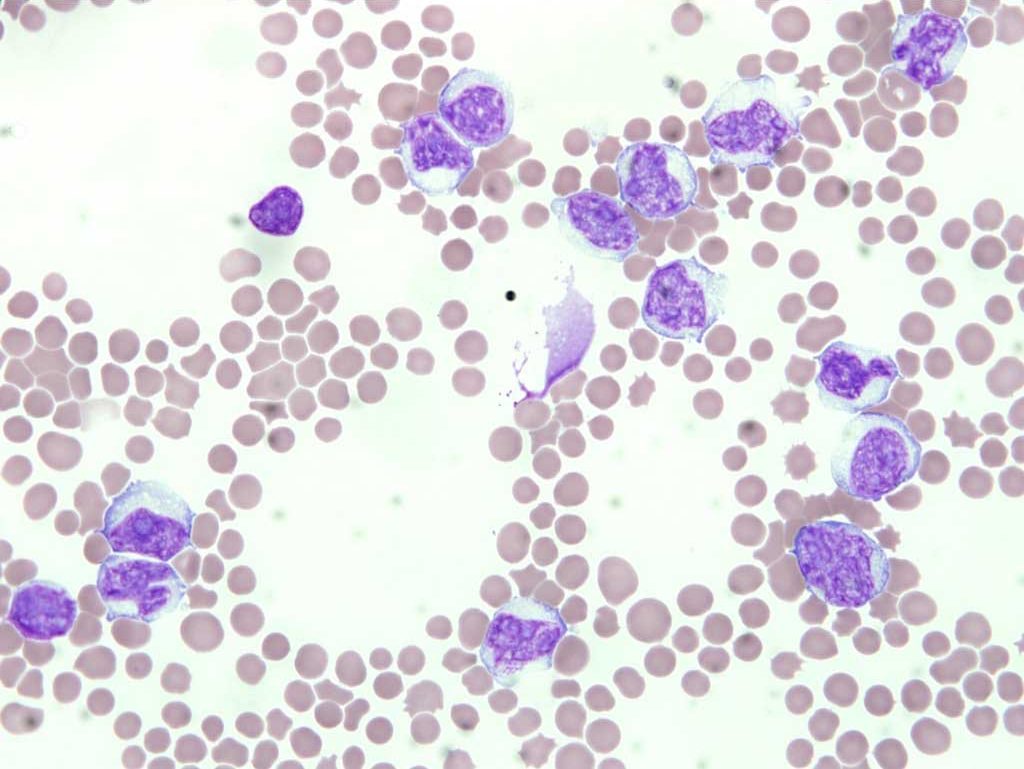

There are two main forms of lymphocytic leukemia: acute lymphocytic (also called acute lymphoblastic) and chronic lymphocytic. With acute lymphocytic leukemia, high numbers of immature lymphocytes (lymphoblasts) are seen in bone marrow and peripheral blood. Neoplastic lymphoblasts are often very fragile cells, perhaps because they have been delayed in their development due to defects in cell cycling and are, therefore, older than normal cells. Cell fragility may result in rupture of the cell membrane when blood smears are made. These ruptured cells are sometimes referred to as “basket” or “smudge” cells, because of the loose woven appearance of free chromatin (Fig. 3.2). Although there are discrepancies in the literature regarding the morphology of a lymphoblast, most clinical pathologists envision a large cell with a prominent nucleolus and often darkly staining cytoplasm, indicating metabolic hyperactivity (Fig. 3.3). This terminology is also consistent with the equivalent stage of development of other hemopoietic cells as shown in Chapter 1: Erythrocytes, (Fig. 1.1). The discrepancy may arise from the fact that hemopoietic stem cells resemble small lymphocytes and theoretically, a more primitive cell than a lymphoblast could form a neoplastic population. Without the use of immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, molecular, or other tests, these primitive cells would be difficult to distinguish from mature, small lymphocytes.

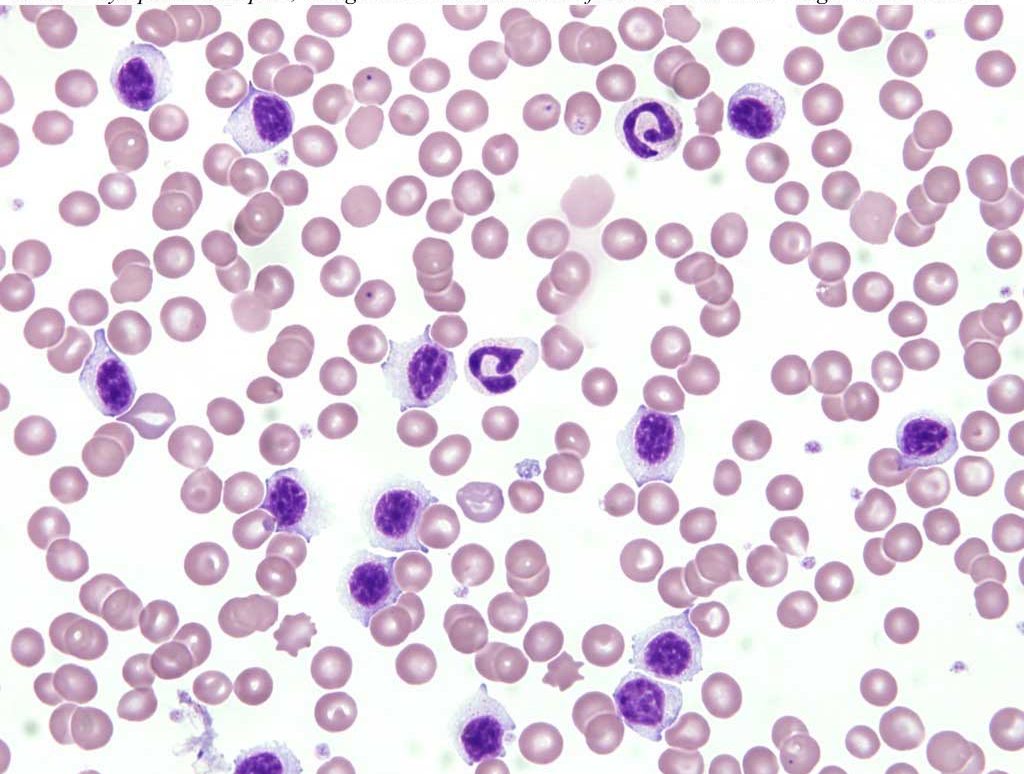

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is characterized by the presence of increased numbers of small lymphocytes, presumed to be mature, in the bone marrow and peripheral blood. These lymphocytes are morphologically normal and the leukemia may be discovered as an incidental finding (see Fig. 3.4). Great care is required on the part of the clinical pathologist in making the diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia because non-neoplastic causes of lymphocytosis must be ruled out.

Clonality tests, such as polymerase chain reaction for antigen receptor rearrangement (PARR), may be used to differentiate between a polyclonal (reactive) proliferation of lymphocytes and a monoclonal (neoplastic) proliferation of lymphocytes. Flow cytometry or immunohistochemistry may be used to identify neoplastic lymphocytes as B or T cell origin, which affects treatment decisions and prognostication. Plasma cell sarcomas and tumors of large granular lymphocytes, two of the more differentiated lymphoid neoplasms, can usually be diagnosed by their distinctive morphologies. Both of these neoplasms are seen in dogs and cats and may be manifested, at least in part, as leukemias.

Feline leukemia virus (FeLV) and hemopoietic neoplasia

LSA and myeloid neoplasms are highly associated with FeLV infection in cats. Exceptions are plasma cell sarcomas, mast cell sarcomas, and large granular LSAs which have not been found to be FeLV-related. Older cats, in particular, are not necessarily viremic at the time of detection of the neoplasm. Therefore, these cats may be negative for circulating viral antigens, using traditional tests such as the commonly available ELISA for group specific antigen (gag) protein 27 (p27). However, viral antigens may be detected within tumor tissue using immunohistochemistry, viral DNA may be detected within tumor tissue using the polymerase chain reaction, or both. Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) appears to be a risk factor for the development of LSA in cats as well, but the mechanism is not clear since virus is not present within neoplastic cells, as with FeLV.

Bovine leukemia virus and lymphoid neoplasia

LSA in adult cattle is most often associated with bovine leukemia virus (BLV) infection. BLV-related LSA is rarely seen in cattle <2 years of age and is most common in the 4 to 8 year range. The virus appears to cause neoplastic disease after a very long incubation period. For this reason, BLV-induced LSA is seen more commonly in dairy cattle due to their relatively long life span compared to beef cattle. Also, housing and husbandry practices for dairy cattle are more likely to contribute to horizontal spread of the virus and the enzootic nature of BLV-induced neoplasms. Solid tumors occur more commonly than lymphocytic leukemia, and bone marrow involvement and leukemia can occur late in the disease. Most cattle infected with BLV do not develop neoplastic disease. About 30% have persistent lymphocytosis which is a polyclonal B lymphocyte immune response to the virus. Only 5-10% of infected cattle develop lymphoid neoplasia – solid tissue tumors, lymphocytic leukemia, or both. The most common sites of solid tumors are lymph nodes, heart, digestive tract (particularly abomasum), liver, spleen, kidneys, uterus, eyes (retrobulbar), and spinal cord. When solid tumors are not present and only bone marrow is affected, distinguishing between lymphocytic leukemia and persistent lymphocytosis can be difficult without molecular tests to determine clonality. Lymphocyte atypia and peripheral blood cytopenia(s) may help in diagnosing lymphocytic leukemia. The agar gel immunodiffusion (AGID test) for serum antibodies to glycoprotein (gp) 51 is the traditional test used for confirming infection with BLV. An ELISA is now available and is reported to be more sensitive as it detects many types of antibodies to BLV, not just anti-gp 51 antibodies. Although the test detects exposure to BLV, it does not confirm the presence of neoplastic disease.

LSA in juvenile cattle (<2 years of age) is not associated with BLV infection, is not transmissible, and affects animals individually rather than in clusters. Sporadic LSA in young cattle usually is manifested as one of three possible forms: multicentric, with involvement of peripheral lymph nodes, spleen, liver, and bone marrow; thymic, with involvement of thymus and anterior mediastinal lymph nodes; and cutaneous, with involvement of the skin.

Large granular Lymphosarcoma

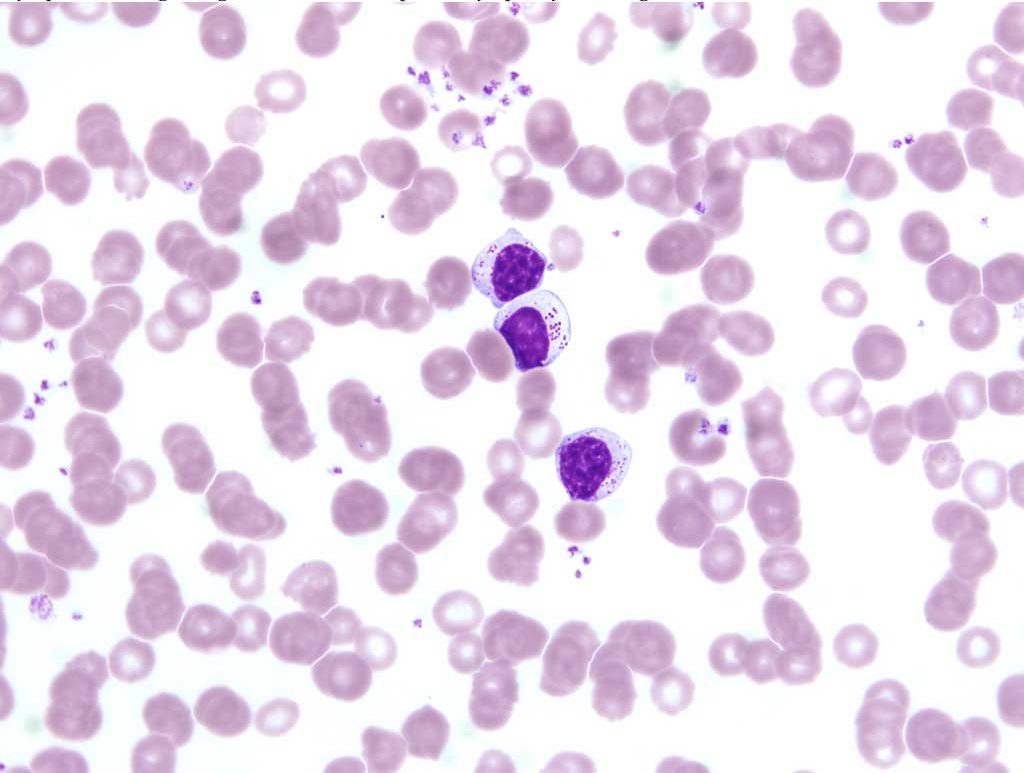

Neoplasms of large granular lymphocytes are not common but are seen in the dog and cat. Tumors usually arise in the abdominal cavity (lymph nodes, spleen, liver, and digestive tract) and may be accompanied by leukemia. Large granular lymphocytes are distinctive due to the presence of large, irregular, magenta granules within the cytoplasm (Fig. 3.5). These cells are thought to represent natural killer cells or cytotoxic T lymphocytes.

Solid malignant lymphoid tumor.

Type of lymphoid neoplasm in which there are increased numbers of lymphoblasts in bone marrow and peripheral blood

Large lymphocyte with prominent nucleolus; may be a lymphocyte precursor or neoplastic lymphocyte.

Ruptured cell visible on blood smear; neoplastic cells are often fragile and prone to rupture. May also be called a smudge cell.

Pluripotential cell that gives rise to all hemopoietic cell lines; also capable of self-renewal.

Type of lymphoid neoplasm in which there are increased numbers of small lymphocytes in bone marrow and peripheral blood.

Technique by which cells in fluids (e.g. blood) can be identified based on cell surface markers.

Technique by which cells in tissue (e.g. poorly differentiated neoplastic cells) can be identified based on cell surface markers.

Malignant neoplastic plasma cells usually within the bone marrow; also referred to as systemic malignant plasma cell tumor, plasma cell myeloma or multiple myeloma. Often accompanied by plasma cell leukemia, bone lysis, hypercalcemia, monoclonal gammopathy, and Bence Jones proteinuria.

Lymphocyte with large magenta cytoplasmic granules; either a cytotoxic T cell or natural killer cell.

Malignant neoplasm of mesenchymal origin, e.g. osteosarcoma.

Cytotoxic lymphocyte important in the non-specific immune response

Lymphocyte involved in cell-mediated immunity; several subsets extst, including helper, cytotoxic, and suppresor T cells