Lymph Node Cytology

Aspiration of enlarged peripheral lymph nodes is easily performed and usually provides valuable information, if not a diagnosis. Normal sized lymph nodes present a challenge to aspirate, but sampling can be useful under some circumstances. For instance, if a node is not enlarged, but feels lumpy or hard, pathology within the node is likely. Many lymph nodes are embedded in or associated with a fat pad which can be misinterpreted as lymph node enlargement. If repeated sampling produces only lipid droplets, the lymph node is probably not enlarged. Mandibular lymph nodes are usually palpable and are often reactive due to their proximity to the oral cavity. The mandibular salivary gland is immediately caudal to the lymph node and may be misinterpreted as an enlarged lymph node. If the material aspirated is tenacious, stringy, and blood-filled, salivary gland aspiration is likely.

Normal and Reactive Lymph Nodes

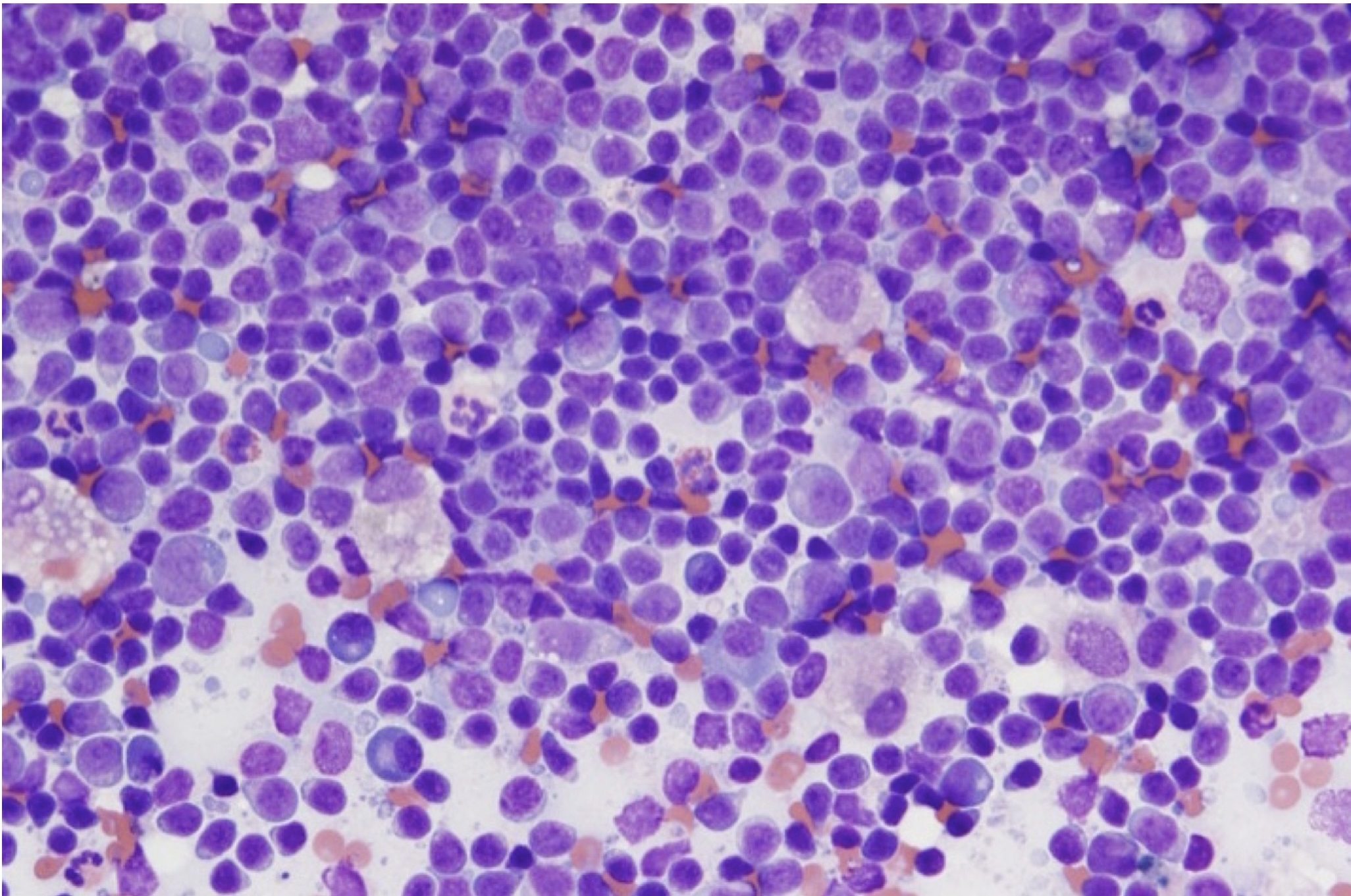

Normal lymph nodes contain a heterogeneous population of lymphocytes, that is, there are lymphocytes of all sizes and stages of maturation and differentiation (Fig. 5.19). Small lymphocytes predominate (approximately 90%), with the remainder being a combination of medium lymphocytes, large lymphocytes, and plasma cells. Both erythrocytes and neutrophils in the background can be used to help decide on the size of the lymphocytes. Small lymphocytes are slightly larger than a mature erythrocyte; medium lymphocytes are approximately 2 times the diameter of an erythrocyte; large lymphocytes are >3 times the diameter. Similarly, small lymphocytes are smaller than a neutrophil; medium lymphocytes are approximately the same size as a neutrophil; large lymphocytes are larger than a neutrophil. Occasional macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils, and mast cells may also be present. Blood contamination of the aspirate will dilute the lymphoid population and relatively higher numbers of peripheral blood leukocytes will be seen.

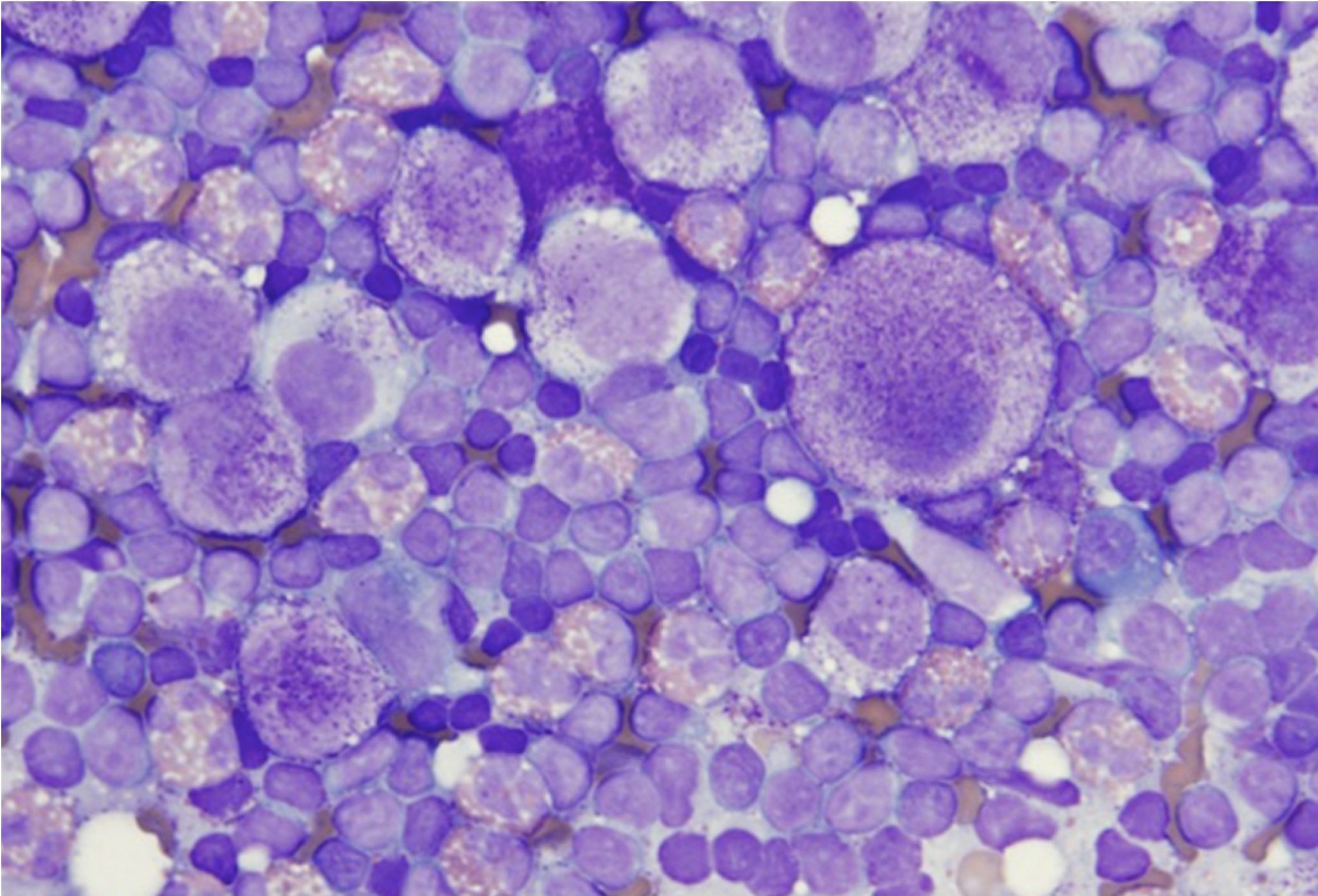

Lymph nodes that are immunologically stimulated are described as reactive or hyperplastic (Fig. 5.27). They have slightly more medium and large lymphocytes than nonreactive nodes, with a concurrent decrease in the proportion of small lymphocytes (70-80% small lymphocytes compared to 90%). There are often increased numbers of plasma cells. Plasma cells resemble lymphocytes, but usually display differentiation with eccentric nuclei (sometimes with a spokewheel pattern of chromatin) and a perinuclear clear (Golgi) zone (Fig. 5.7). Lymph nodes may be reactive due to local or generalized infection, inflammation, or immune-mediated disease.

Lymphadenitis

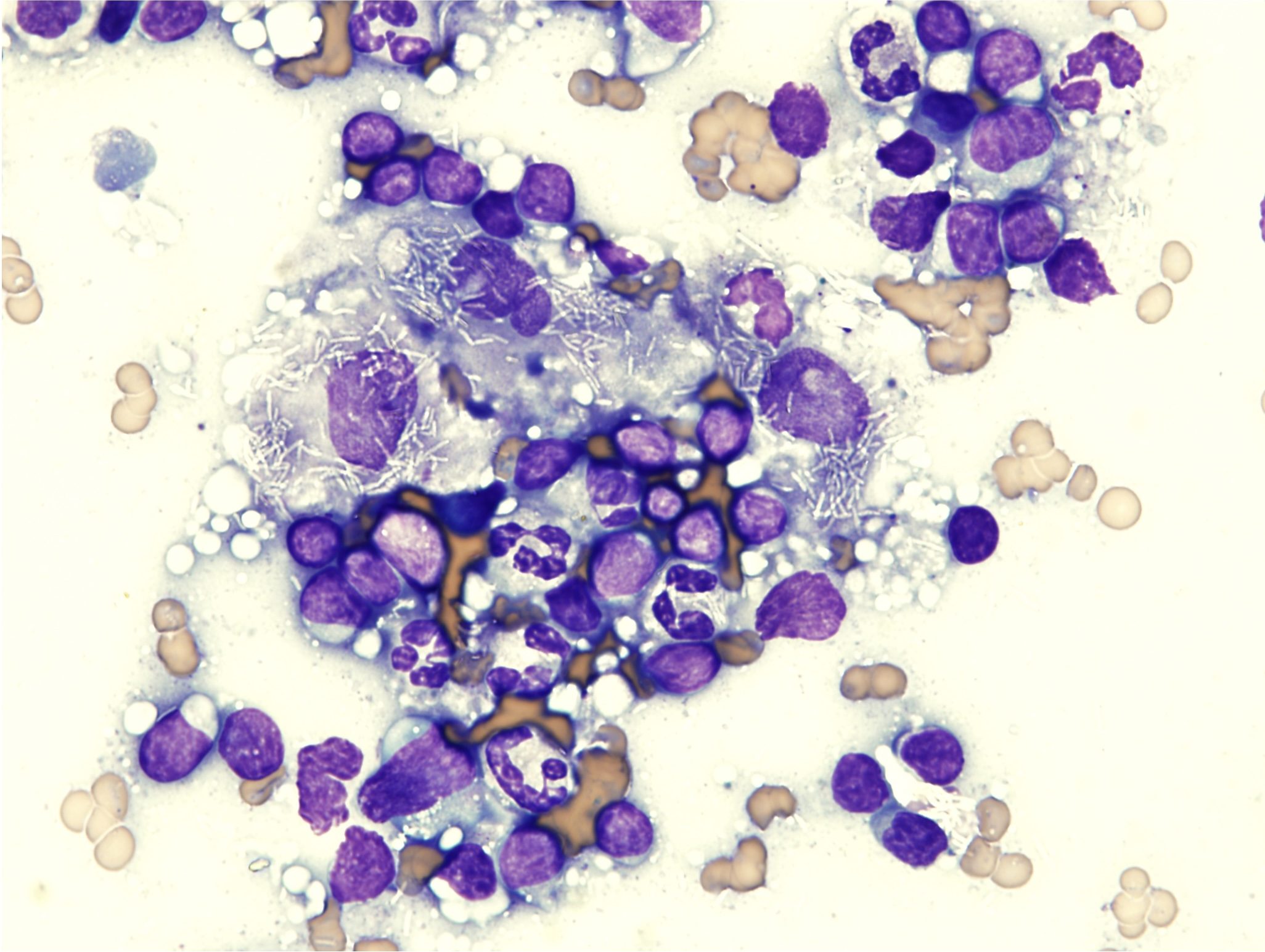

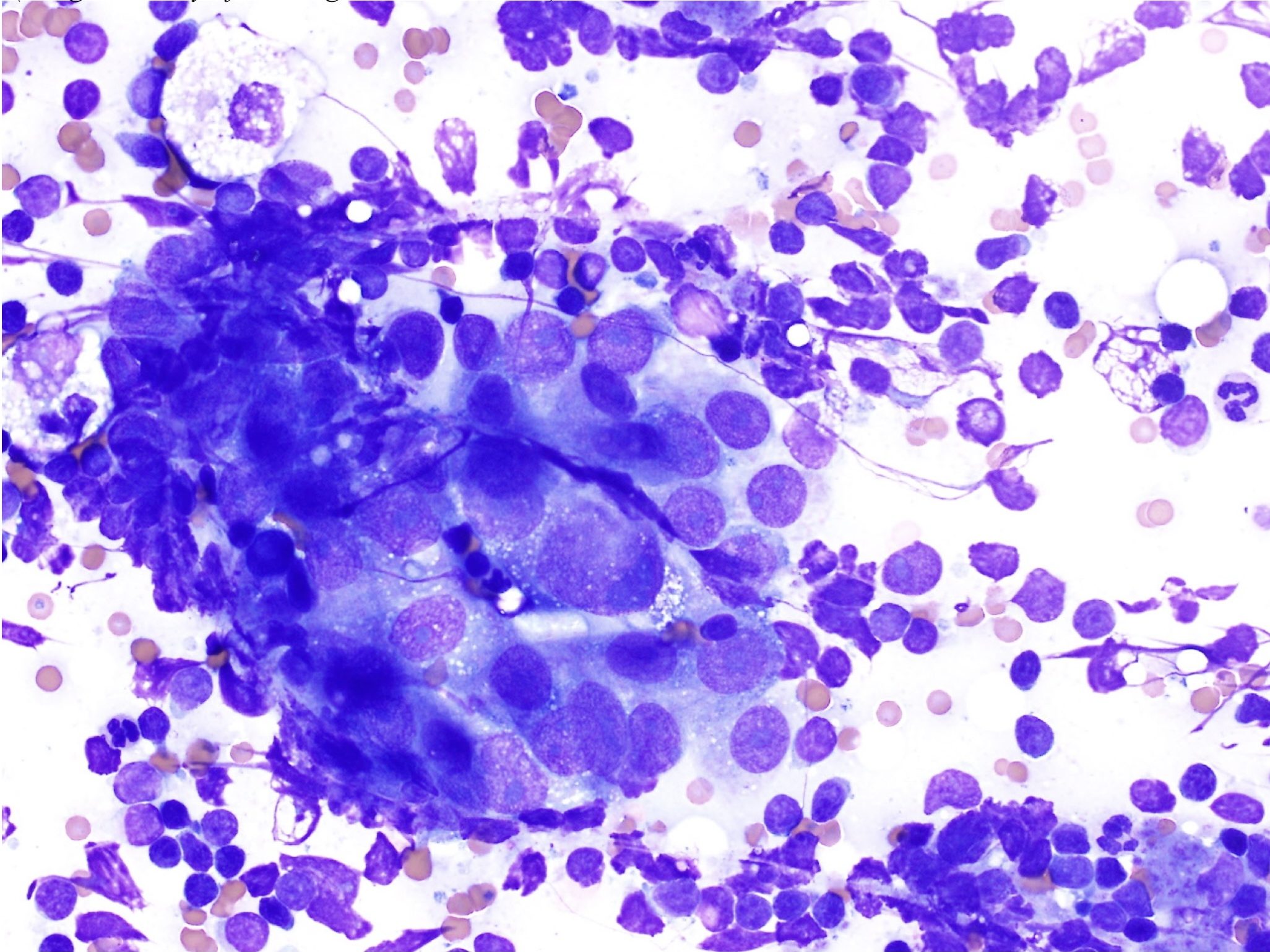

With lymphadenitis, there are increased numbers of inflammatory cells within the node. The type of inflammatory cell will vary with the cause and the duration of the problem. Acute septic disorders are likely to result in increased numbers of neutrophils within the regional node(s). Parasitic or allergic skin disease could result in increased numbers of eosinophils and mast cells in the local lymph node. Chronic infections may be associated with increased numbers of macrophages. For example, blastomycosis often causes a mixed neutrophilic and macrophagic lymphadenitis such that increased numbers of neutrophils, macrophages, and multinucleate giant cells may occupy much of the lymph node (Fig. 5.9). Mycobacteriosis also generally results in macrophage-rich inflammation, with non-staining organisms inside macrophages (Fig. 5.28).

Metastatic and Lymphoid Neoplasia

The presence of noninflammatory cells that are not usually seen in lymph nodes should signal the possibility of metastatic neoplasia (Fig. 5.29 and Fig. 5.30). Carcinomas, mast cell tumors, and melanomas frequently metastasize to local or distant lymph nodes, and lymph node aspiration can be invaluable in staging some malignancies. Staging involves evaluating lymph nodes and other organs such as lungs or liver for evidence of metastasis of a tumor, and it provides valuable information on prognosis.

Lymphosarcoma is one of the most common malignancies in domestic animals. It should be noted that the term lymphoma is often used interchangeably with lymphosarcoma and refers to a malignant process. Affected lymph nodes are nonpainful and often greatly enlarged. Malignant lymphocytes are fragile and great care must be taken when making smears of aspirated material. Occasionally cloudy or blood-tinged fluid is aspirated and this can be deposited into an EDTA tube for cytospin smear preparation at the diagnostic laboratory. Cell preservation is often improved with cytospin preparation compared to direct smearing.

Lymphosarcoma (Fig. 5.22) presents a picture of homogeneity (uniformity) instead of the normal heterogeneity of the lymph node (Fig. 5.19 and Fig. 5.27). The majority (>50%) of cells will be medium or large lymphocytes. Often nucleoli are large, prominent, and irregularly shaped. The cytoplasm may be darkly stained and occasionally finely vacuolated. Mitotic figures are increased and may be abnormal. There may be abundant cytoplasmic fragments in the background which are the result of increased cell fragility.

In some cases, the diagnosis of lymphosarcoma may be difficult to confirm based on cytology alone, for example, when large lymphocytes do not predominate (e.g. in the early stages of the disease), or when the mandibular lymph nodes are sampled and a reactive population is present as well as a potentially neoplastic population. This situation may present a dilemma even for the experienced clinical pathologist. Sampling additional nodes, repeating aspirates at a later date, or obtaining biopsies for histopathology may facilitate the diagnosis. For canine and feline patients, a clonality assay (PCR for antigen receptor rearrangements or PARR assay; see Chapter 3: Hemopoietic Neoplasia) may be useful in confirming the presence of a neoplastic population of lymphocytes.

General term for fat, including triglycerides, phospholipids, cholesterol.

Lymph node responding to immunologic stimulation; often recognized cytologically by the presence of numerous plasma cells and a heterogeneous population of large, intermediate, and small lymphocytes.

Red blood cell (RBC); an anucleate (in mammalian species) cell containing hemoglobin needed for oxygen transport. Typically shaped like a bi-concave disk.

Granulocyte with fine, inconspicuous cytoplasmic granules and a segmented nucleus; important in phagocytosis and killing of bacteria.

Referring to lymphocytes and tissues where lymphocytes develop.

White blood cell (WBC); includes neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, mast cells.

Inflammation of the lymph node.

Abnormal uncontrolled growth of cells that are unresponsive to normal physiologic growth controls; may be benign or malignant.

Method of preparing a concentrated sample for evaluation of cell poor fluids.