Laboratory Evaluation of Hemostasis

Normal hemostasis requires interactions among blood vessel walls, platelets, and coagulation factors. The fibrinolytic system and other natural anticoagulants ensure that thrombosis is not a sequel to hemostasis.

Defective Hemostasis:

- Disorders of primary hemostasis:

Blood vessels

Platelets – number, function, or both

von Willebrand factor

- Disorders of secondary hemostasis:

Coagulation factor deficiency

Coagulation factor inhibitors

- Disorders of factors regulating hemostasis and fibrinolysis can result in either thrombosis or hemorrhage.

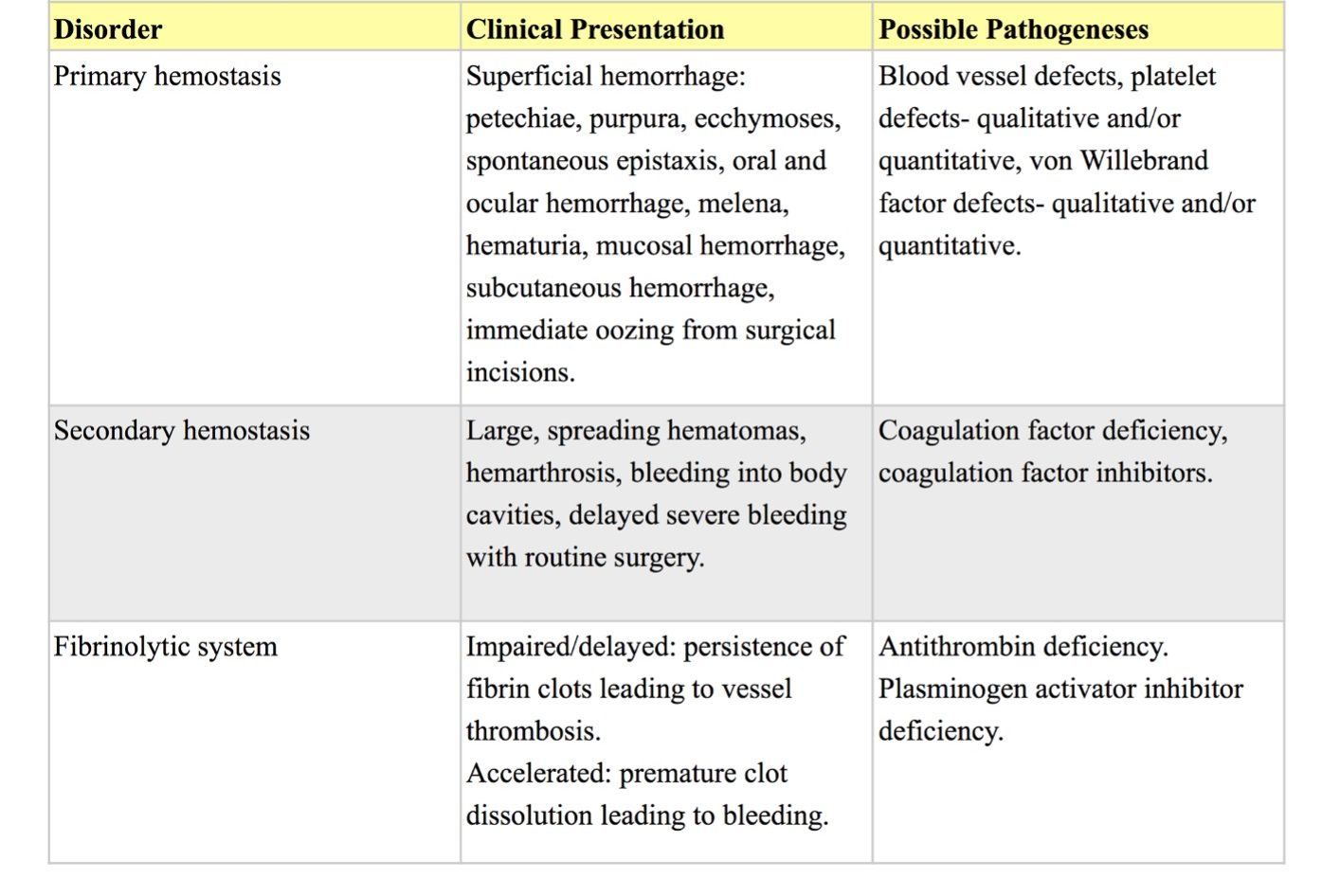

Clinical presentation (Table 4.3):

Disorders of primary hemostasis generally result in superficial hemorrhages involving skin and mucosal surfaces. Petechial, purpural (up to 1 cm), and sometimes ecchymotic (larger than 1 cm) hemorrhages are the hallmark of vascular or platelet disorders. With routine surgery, persistent oozing from skin incisions and small/non-ligated vessels may be noted. Normal daily functions may result in epistaxis (nosebleed), oral and ocular hemorrhages, melena (dark/digested blood in the feces), hematochezia (bright/fresh blood in the feces), hematuria (blood/intact RBCs in the urine), and subcutaneous hemorrhages. Trauma superimposed on disorders of primary hemostasis can result in larger hematoma formation mimicking disorders of secondary hemostasis.

Disorders of secondary hemostasis are more likely to result in large spreading hematomas, hemarthrosis (bleeding into a joint cavity), and bleeding into body cavities. With routine surgery, delayed severe bleeding may occur.

Impaired or delayed fibrinolysis results in persistence of fibrin clots producing clinical signs referable to the anatomic site of the thrombosed vessel(s). Accelerated fibrinolysis results in premature dissolution of formed fibrin clots producing clinical signs similar to a coagulopathy. Disorders of naturally occurring plasma inhibitors of coagulation and fibrinolysis can result in either thrombosis (e.g. AT deficiency) or hemorrhage (e.g. plasminogen activator inhibitor deficiency). These situations are uncommon, require complex diagnostic testing, and will not be discussed here.

Simultaneous disorders of coagulation and fibrinolysis suggest generalized derangement of the hemostatic process as seen in disseminated intravascular coagulation and fibrinolysis (DIC&F).

Diagnostic Approach

- History/signalment

- Physical examination

- Diagnostic tests

1 and 2 are very important in establishing the appropriate choice and sequence of diagnostic testing.

Complete blood count (CBC)

A CBC is always the first test to perform when presented with a bleeding patient. Thrombocytopenia, either immune-mediated or from other causes, is the single most important cause of bleeding in veterinary medicine. Information gained from the CBC includes, but is not limited to: platelet numbers and morphology; presence or absence of anemia; if anemic, whether regenerative or nonregenerative, hypochromic, etc.; red cell morphology (e.g. schizocytes, keratocytes as in DIC&F); presence or absence of inflammation, cytopenia(s), leukemia; and plasma protein concentration which may help determine if blood loss is acute.

Particularly in an emergency situation, the blood smear may have to be interpreted immediately and “in clinic”. An automated or semi-automated platelet count should always be re-evaluated by smear examination since results may be greatly affected and misinterpreted due to spontaneous platelet clumping. Provided platelets are evenly distributed and not clumped on the smear, 8-10 per 100x (oil) field would equate to about 200 x 109/L; less than 2-3 per 100 x field would equate to less than 50 x 109/L, a count at which spontaneous hemorrhage could occur. If platelet clumping is present on smear evaluation, either at the feathered edge or within the body of the smear, then one must judge whether there are adequate platelets. A manual count, as above, should still be done, but with the realization that this will be an underestimate due to the presence of platelet clumping.

Stains used for blood smears should be maintained and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions or there may be difficulty interpreting platelet numbers, as well as many other important morphologic assessments such as hemoglobin content of erythrocytes, polychromasia, and toxic change. Equine platelets often stain more faintly than other species and smears should be carefully evaluated. Note that there are species differences with respect to the RI for platelet counts. There are also within species or breed differences that should be taken into consideration. For example, Greyhound dogs typically have lower platelet counts than other breeds. Also, an inherited platelet disorder affects approximately 50% of Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS) dogs resulting in macrothrombocytopenia. Although platelet counts are below the RI, platelet mass is normal, due to the large size of the platelets, and these dogs do not experience bleeding tendencies. The same mutation responsible for macrothrombocytopenia in CKCS dogs has now been identified in dogs of several other breeds.

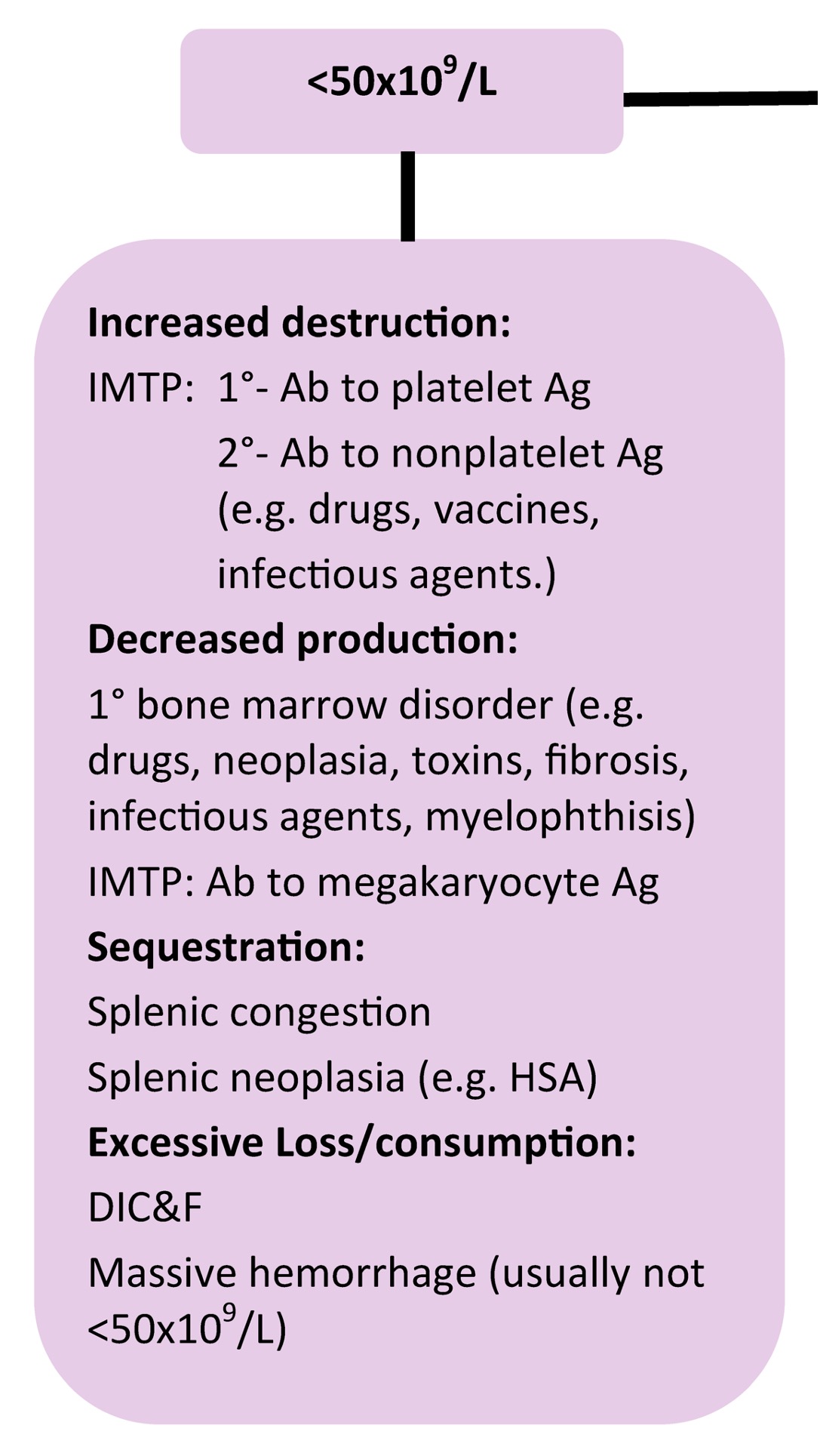

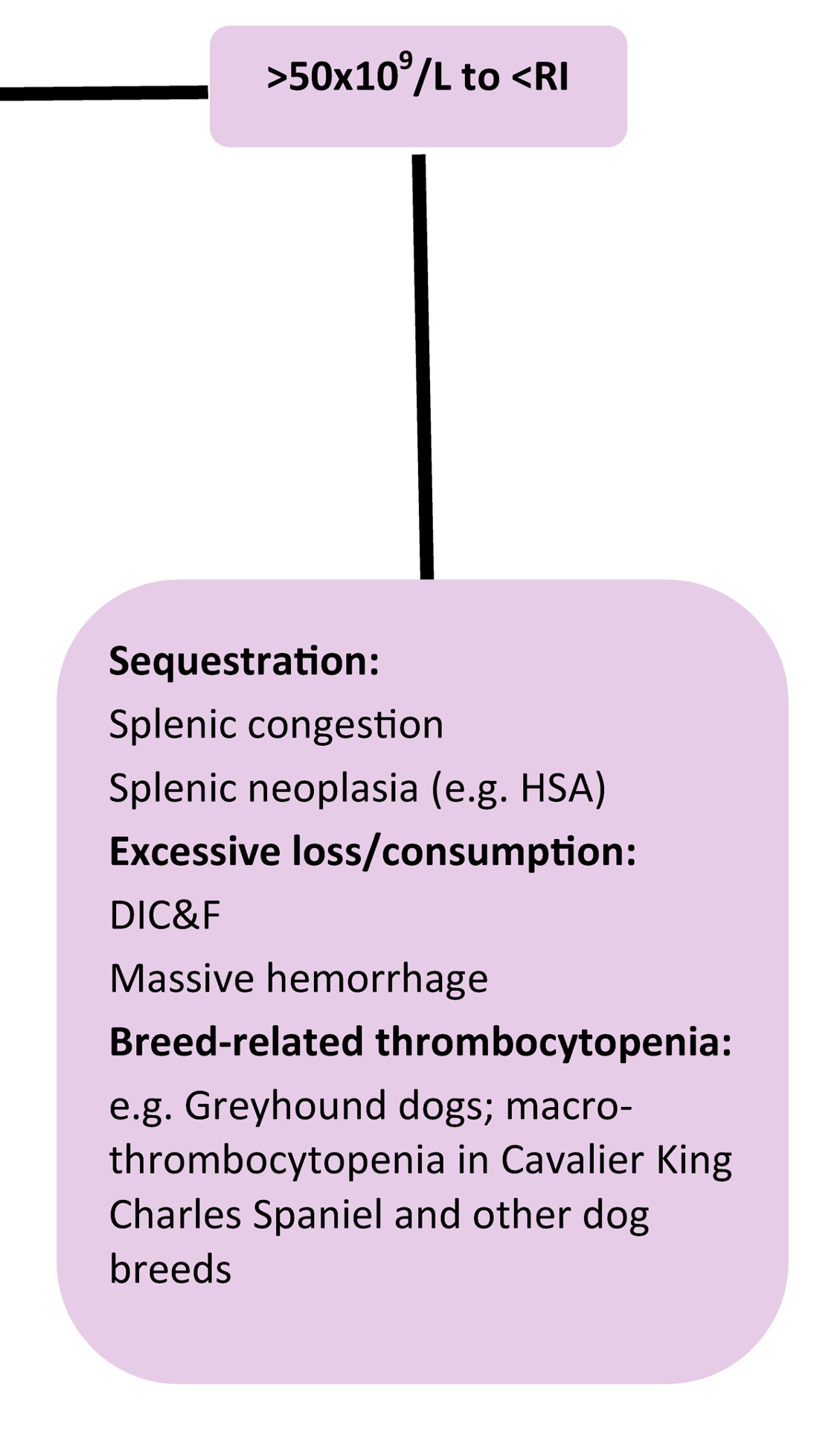

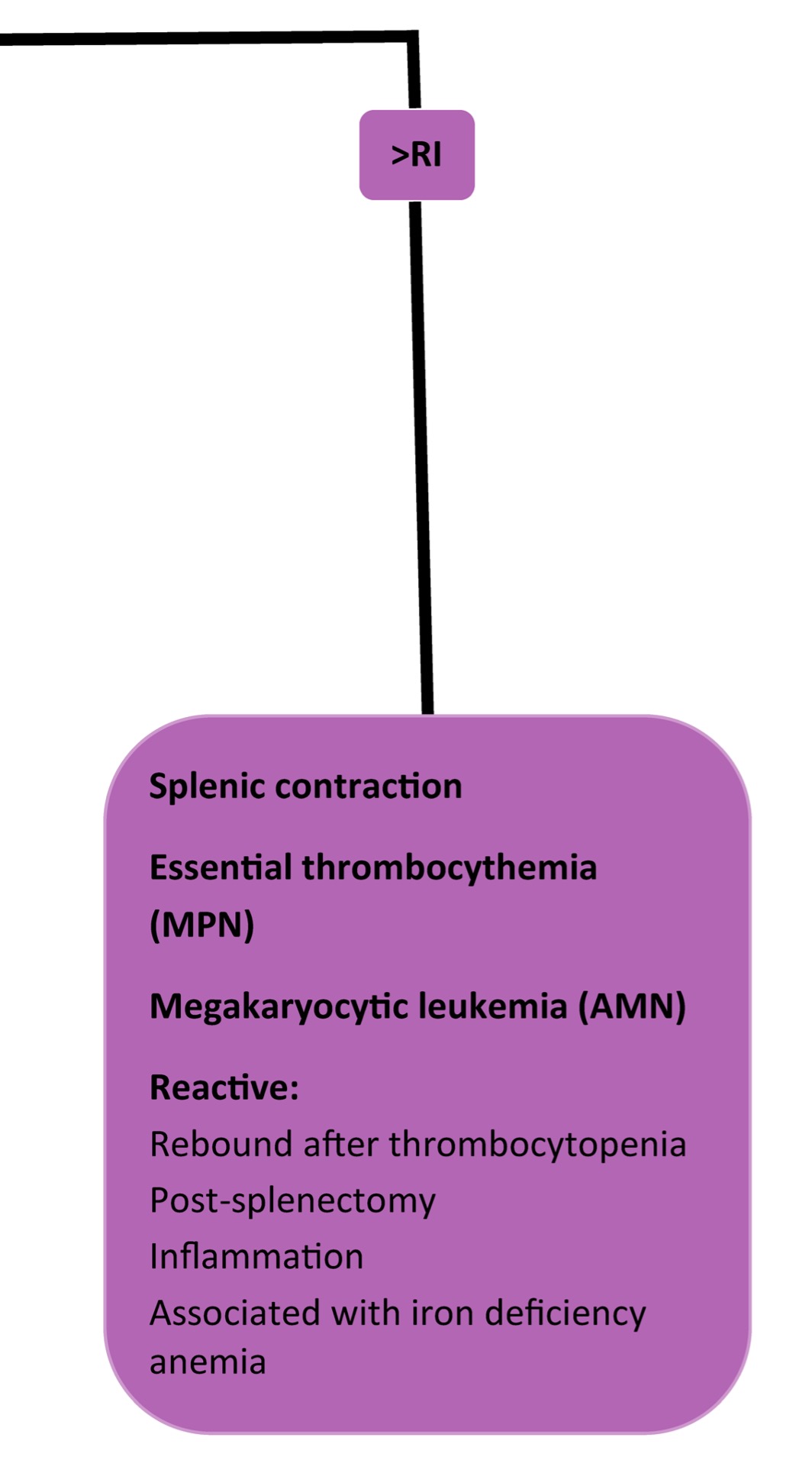

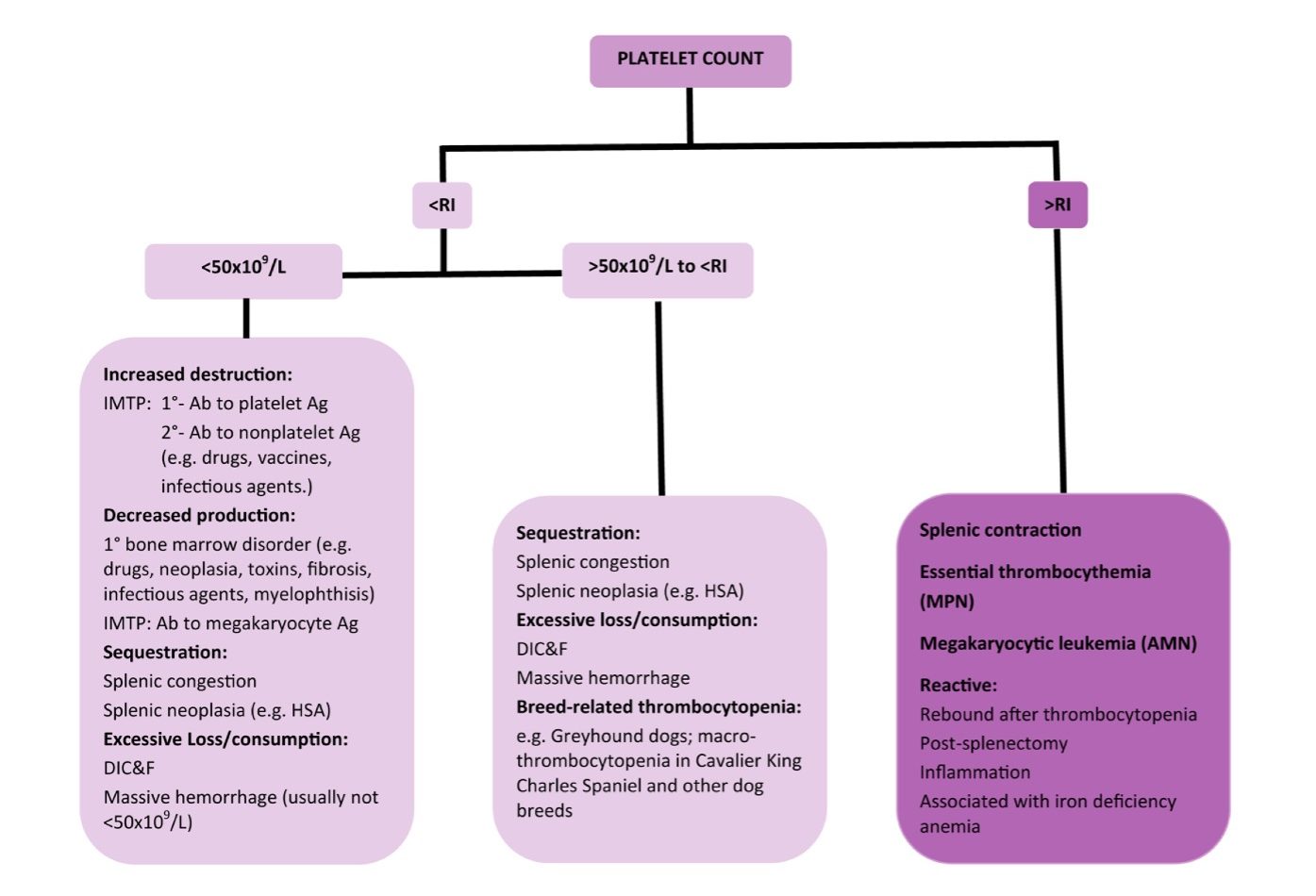

When platelet numbers are above or below the RI, potential causes should be considered as well as determining if the finding is likely to affect primary hemostasis. See Fig 4.8 for mechanisms of both thrombocytopenia and thrombocytosis. Bone marrow examination may be particularly useful when thrombocytopenia or thrombocytosis is detected, but the mechanism is not known. Bone marrow examination is also indicated when IMTP has been diagnosed, treatment has been initiated, and response to treatment is poor. Also, if there is concurrent neutropenia, nonregenerative anemia, or suspicion of leukemia on peripheral blood examination, bone marrow examination is useful to rule in or out underlying disease. With idiopathic or primary IMTP we expect to see megakaryocytic hyperplasia, provided there has been sufficient time for accelerated megakaryopoiesis. Occasionally animals (especially dogs) are presented in the very early stages of the disease, and only after several days and repeated bone marrow examination, is evidence of increased megakaryopoiesis seen. Other animals (again, usually dogs) may experience chronic, intermittent forms of thrombocytopenia. These dogs often have classical findings of iron deficiency anemia on peripheral blood examination (microcytic, hypochromic anemia, sometimes with inadequate regeneration) and depleted bone marrow iron stores. Increased bone marrow plasma cell numbers may occur in cases of IMTP, presumably due to stimulated antibody production. Lack of megakaryopoiesis after a period of about 2 weeks suggests immunologic attack of megakaryocyte precursors or marrow suppression due to drugs, toxic agents, or neoplasia. Blood should always be collected for a CBC at the same time as bone marrow evaluation.

Bleeding time

If platelet numbers do not support thrombocytopenia as the cause of bleeding, but the clinical presentation is consistent with a defect of primary hemostasis, then the buccal mucosal bleeding time (BMBT) should be evaluated. The BMBT can be done in house using a commercially available bleeding time device. If prolonged, then consider a platelet function defect which may be intrinsic or extrinsic to the platelet, inherited, or acquired. Examples of platelet function defects are vWD (extrinsic to the platelet), deficiencies or defects in the platelet receptor for vWF or the fibrinogen receptor, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug administration, particularly ASA. There are many other hereditary platelet function defects that will not be described here except to provide one example. A platelet aggregation defect has been reported in Simmental and Simmental X cattle. The defect involves signal transduction and platelets do not respond normally to agonists. The disorder is very similar to that described in Basset Hound and Eskimo Spitz dogs. Affected cattle may experience epistaxis in cold weather, and bleeding from vaccination sites, dehorning, ear tagging, tattooing, insect bites, and at parturition. Rarer causes of prolonged bleeding time involve blood vessel disorders such as collagen defects.

There is no indication for performing a BMBT in the face of thrombocytopenia unless the platelet count is not sufficiently low to explain the bleeding, and a concurrent platelet function defect is suspected. If the BMBT is not prolonged, then the clinical examination should be repeated to determine if local disease is responsible for the bleeding. For example, neoplastic or inflammatory disease involving the nasal passages or oral cavity could result in nasal or oral bleeding mimicking a disorder of primary hemostasis.

von Willebrand Factor (vWF)

vWD has been identified in many breeds of dogs, but is rare in most other domestic species. Clinical features mimic thrombocytopenia because vWF is an adhesive protein which binds platelets to subendothelial collagen when vessel damage first occurs. However, as stated earlier, some dogs do not experience spontaneous bleeding with vWD but only develop clinical signs with additional mucosal injury beyond normal daily events. Therefore, mucosal bleeding varies from mild to severe and may be exacerbated by conditions such as deciduous teeth eruption, rhinitis, and enteritis (e.g. parvoviral enteritis). Platelet numbers are usually within RI and the BMBT is prolonged. Diagnosis requires laboratory measurement of vWF. Most laboratories currently quantitate VWF antigen using an ELISA technique; results are expressed as a percent of normal where pooled normal plasma is assigned a value of 100%. Proper collection, handling, and submission of plasma are critical. Results are invalidated if there is hemolysis, sample heating, clotting, or contact with nonsiliconized glass (see Protocol Manual on the website).

Three types of vWD have been identified. Type I is most common and has been reported in over 50 breeds of dogs. The decrease in vWF antigen involves all multimers (aggregates of vWF single units/monomers held together by noncovalent bonds) of the protein. Clinical signs are highly variable with many dogs leading relatively normal lives, although extra precautions may be necessary with nail trimming, and more invasive activities such as dental and surgical procedures. Type 2 vWD involves a disproportionate decrease in the much more functional high molecular weight vWF multimers, resulting in more severe and often life-threatening bleeding. Though rare, type 2 disease has been reported in German Shorthaired Pointer and German Wire-haired Pointer dogs. With type 3 vWD, vWF is absent and affected animals may die in utero or shortly after birth. Type 3 disease has been reported in the following dog breeds: Chesapeake Bay Retriever, Scottish Terrier, Shetland Sheepdog, and Dutch Kooiker.

Platelet function tests

Platelet function tests include evaluation of platelet adhesion, aggregation, release, contraction, and procoagulant activity. Referral laboratories with expertise in hemostasis testing are more likely to offer these specialized tests than regular diagnostic laboratories. Platelet function testing is indicated when clinical signs are consistent with a disorder of primary hemostasis and causes such as thrombocytopenia and vWD have been ruled out. Animals with dysproteinemias, NSAID intake, cyclooxygenase deficiency, and other platelet function disorders may have abnormal responses to aggregating agents.

Coagulation tests

If clinical findings, history, signalment, and nature of the bleeding are more suggestive of a disorder of secondary hemostasis (i.e. a coagulopathy), then coagulation screening tests should be performed. See Protocol Manual for information on sample collection and handling.

An activated clotting time (ACT) can be done in house in an emergency situation. The commercially available ACT tubes contain an agent which activates the early contact factors involved in the intrinsic pathway. Even though phospholipid is not added to the ACT tube, severe thrombocytopenia does not have a significant effect on the test. The ACT measures the intrinsic and common pathways similar to the PTT, but the PTT is a more sensitive test. The ACT will be prolonged when a coagulation factor(s) in the intrinsic pathway (VIII, IX, XII, prekallikrein, HMWK), or common pathway (fibrinogen, prothrombin, V, X), or both is less than 10% of normal activity, whereas, the PTT will detect a deficiency at 30% of normal activity. Factor XII, prekallikrein, and HMWK are contact factors and although deficiencies can have a marked effect on the ACT and PTT, spontaneous bleeding due to these deficiencies is rare to non-existent.

Prolongation of the PT with normal PTT localizes the problem to factor VII. Prolongation of the PTT with normal PT localizes the problem to factor XII, prekallikrein, HMWK, factor XI, factor IX, or factor VIII. Prolongations in both PT and PTT indicate common pathway disorders (fibrinogen, prothrombin, factor V or factor X) or multiple factor involvement as seen with consumption coagulopathies, circulating inhibitors, or vitamin K deficiency or antagonism (e.g. toxicity from coumarin derivatives as with mouldy sweet clover or rodenticide ingestion). Since factor VII has the shortest half-life of the vitamin K-dependent factors (factors II, VII, IX, and X), the PT is prolonged first following ingestion of coumarin derivatives. Usually both PT and PTT are prolonged when clinical bleeding is detected. However, in some cases, owners have witnessed the ingestion or there is an attempt to avert a herd problem and testing is done at a time when only the PT is affected.

Vitamin K antagonism due to ingestion of rodenticide (in small animals) or mouldy sweet clover (in large animals) represents the most common cause of coagulopathy in veterinary medicine. The second most common cause is DIC&F. Hereditary factor deficiencies are uncommon and specific factor assays, usually only available at referral laboratories, must be performed to confirm these deficiencies.

Blood obtained by rapid, efficient venipuncture with minimal damage to the blood vessel and surrounding tissues may not clot in a serum tube for several minutes. If there is no reason to suspect a coagulopathy in the patient, then the supposed delay is likely due to both the lack of tissue factor (to trigger the extrinsic system) and the lack of a negatively charged surface in the siliconized serum tube (to trigger the intrinsic system). Abnormalities are best detected by submitting appropriate samples for measuring the PT and PTT.

Evaluation of hemostasis in whole blood

Thromboelastography (TEG) and thromboelastometry (TEM) are tests that evaluate the entire clotting process using whole blood. The principle of TEG and TEM is the same but different commercially available instruments are used. These tests provide information on clot development, stability, and fibrinolysis which mimics in vivo hemostasis. Hyper- as well as hypocoagulable conditions may be detected using these instruments. Therefore, their use may assist clinicians with treatment decisions, particularly in emergency situations involving trauma or serious illness. Many reports on the application of TEG and TEM in veterinary medicine have been in experimental studies and it is likely that evaluation of patients in clinical situations will be reported with increasing frequency.

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation & Fibrinolysis; simultaneous disorders of coagulation and fibrinolysis due to generalized derangement of hemostasis.

Decrease in hematocrit (PCV) recognized on the complete blood count (CBC); usually hemoglobin concentration and RBC numbers are also decreased.

An erythrocyte fragment created by shearing trauma to erythrocytes within the vascular system; often the fragment which has been sheared off to form a keratocyte.

Crescent-shaped cells that are formed from mechanical shearing (usually due to fibrin strand deposition) of the red cell.

Presence of bone marrow-derived neoplastic cells in peripheral blood.

Edge of the blood smear farthest from where the droplet of blood is placed.

Oxygen-carrying molecule within erythrocytes.

Increased numbers of anucleate, immature erythrocytes that stain bluish-pink with Romanowsky stains due to the presence of cytoplasmic RNA.

Cytoplasmic abnormalities seen in neutrophils that have not matured normally in the bone marrow. Abnormalities include retention of primary granules, vacuolation, darker staining due to retention of ribosomes, and deposits of rough endoplasmic reticulum (Döhle bodies).

Decrease in the number of neutrophils in peripheral blood below the reference interval for the species.

Of unknown cause.

Cellular proliferation- increased number of normal cells.

Anemia in which there is insufficient body iron for effective erythropoiesis, usually caused by chronic external blood loss. Anemia remains regenerative until the end-stage of iron deficiency. The anemia is characterized by microcytic hypochromic RBCs.

Terminally differentiated B lymphocyte that secretes specific antibody.

Abnormal uncontrolled growth of cells that are unresponsive to normal physiologic growth controls; may be benign or malignant.

Also called buccal mucosal bleeding time (BMBT); diagnostic test used to assess primary hemostasis and platelet function. BMBT is not indicated when bleeding is attributed to thrombocytopenia.

Erythrocyte rupture or destruction; may occur in vitro or in vivo as a pathologic process.

Activated clotting time; cage-side diagnostic test used to evaluate the intrinsic and common coagulation pathways.

Prefix meaning increased.