Body Water

Body water is provided by ingestion of food and water, and through oxidative metabolism. Losses of body water occur through the urinary, digestive, and respiratory tracts, and by evaporation through the skin. Maintenance of body water balance is an active homeostatic process. Thirst regulates water intake and the kidney provides the main regulation of water loss from the body.

The 2 major hormones involved in this regulation are aldosterone and antidiuretic hormone (ADH). Aldosterone synthesis and secretion from the adrenal cortex is stimulated by angiotensin II and increased plasma potassium concentrations. Increased angiotensin synthesis is stimulated by decreased extracellular fluid (ECF) volume (decreased blood pressure). Aldosterone increases sodium reabsorption and potassium excretion by the kidney, resulting in expansion of the ECF volume since water reabsorption occurs when sodium is reabsorbed. ADH secretion increases with increased ECF osmolality, causing animals to be thirsty and drink. ADH also decreases renal water loss by making the collecting ducts more permeable to water. Therefore, more water is reabsorbed.

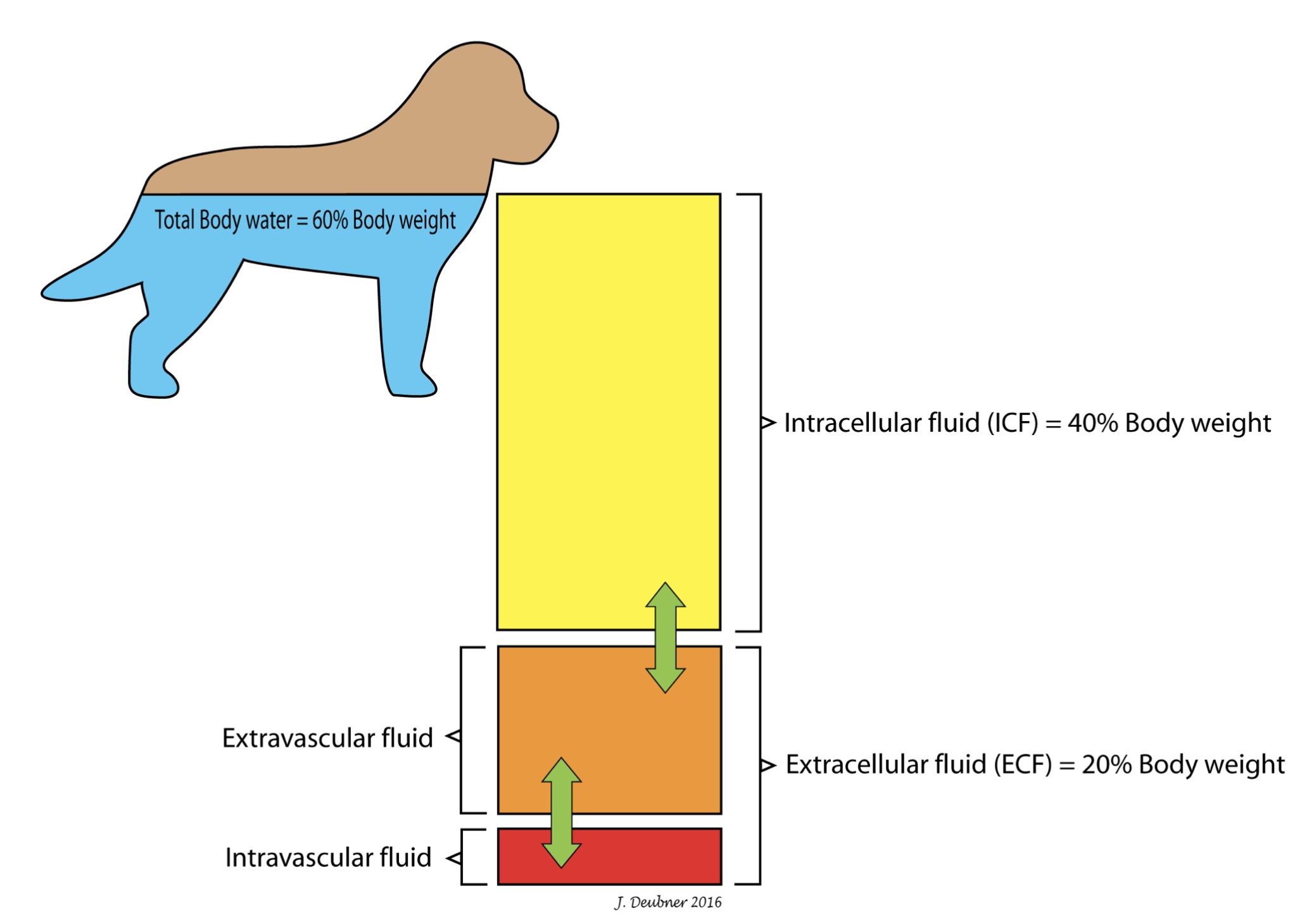

Total body water (TBW) comprises about 60% of an adult animal’s body weight. Two-thirds of TBW is intracellular and one-third is extracellular. In the adult animal, three-quarters of the ECF is extravascular and one-quarter is intravascular (Fig. 6.1). ECF comprises a greater proportion of body weight in neonates compared to adults.

Abnormal body water balance

An increase in TBW can occur with increased fluid intake. For example, young calves will sometimes drink excessively when they first learn how to use a water bowl. Iatrogenic increases in TBW can occur with overzealous fluid therapy. Abnormally high ADH release, as seen with the syndrome of inappropriate ADH release (SIADH), also causes an increase in body water. With this condition, ADH release occurs in the absence of the two normal stimuli for its release – hypernatremia and plasma hyperosmolality. This situation can occur with certain central nervous system lesions, administration of certain drugs, and pathologic conditions of low perceived fluid volume, such as congestive heart failure or hepatic failure accompanied by hypoalbuminemia.

A decrease in TBW occurs with decreased fluid intake and with increased water losses through diarrhea, vomiting, polyuria, severe sweating, or polypnea.

Redistribution of TBW occurs when intravascular water enters extravascular spaces, as with increased hydrostatic pressure and hypoalbuminemia. In states of shock, fluid will pool in extravascular spaces. Also, pathologic conditions involving a body cavity can result in fluid accumulation in that cavity. This is known as third space loss and can be seen with uroabdomen and inflammatory processes such as peritonitis and pleuritis.

Laboratory evaluation of water balance

With a significant decrease in TBW, the Hct or PCV and total protein may be elevated. Similarly, with a significant increase in TBW, the Hct or PCV and total protein will be decreased. These measurements have limitations as their RI are wide, and an alteration from normal could occur without being flagged as outside the RI. These measurements may be particularly useful when monitoring an individual animal over time.

With severe TBW depletion, serum urea and/or creatinine may be increased, known as prerenal azotemia. A USG ,that indicates appropriate concentrating ability would also be expected. With increased TBW, serum urea and creatinine might be below the RI and associated with dilute/hyposthenuric urine (see Chapter 7: Renal System).

Concentration of osmotically active particles in solution expressed in osmoles of solute per kg of solvent (mmol/kg).

Leakage of urine into the abdomen due to trauma, inflammation/infection, or neoplasia involving the urinary tract.

Increases serum urea and/or creatinine.