Plasma Cell Neoplasms

Although plasma cells are differentiated B lymphocytes, plasma cell neoplasms are treated as a distinct entity due to their manifestations and effects on the host. Plasmacytomas are localized proliferations of plasma cells which can be cutaneous or, less commonly, at internal sites, particularly involving the intestinal tract, spleen, kidneys, and nervous system. Cutaneous plasmacytomas display benign behaviour, despite frequent pleomorphism, heterogeneity, anisocytosis, anisokaryosis, and multinucleation (see Chapter 5: Cytology, plasmacytoma Fig. 5.23). If these tumors truly are benign, then cutaneous plasmacytomas may represent an exception to the rule that tumors of lymphocytes are necessarily malignant. Although metastasis of cutaneous plasmacytomas is rare, recurrence following surgical removal and local invasion sometimes occur, which may be considered characteristics of malignancy. Plasmacytomas involving internal soft tissues often metastasize and are considered malignant. Although the term plasmacytoma would be appropriate for a benign tumor of plasma cells, systemic malignant plasma cell tumor or plasma cell sarcoma may be more appropriate when the tumor is known to be malignant.

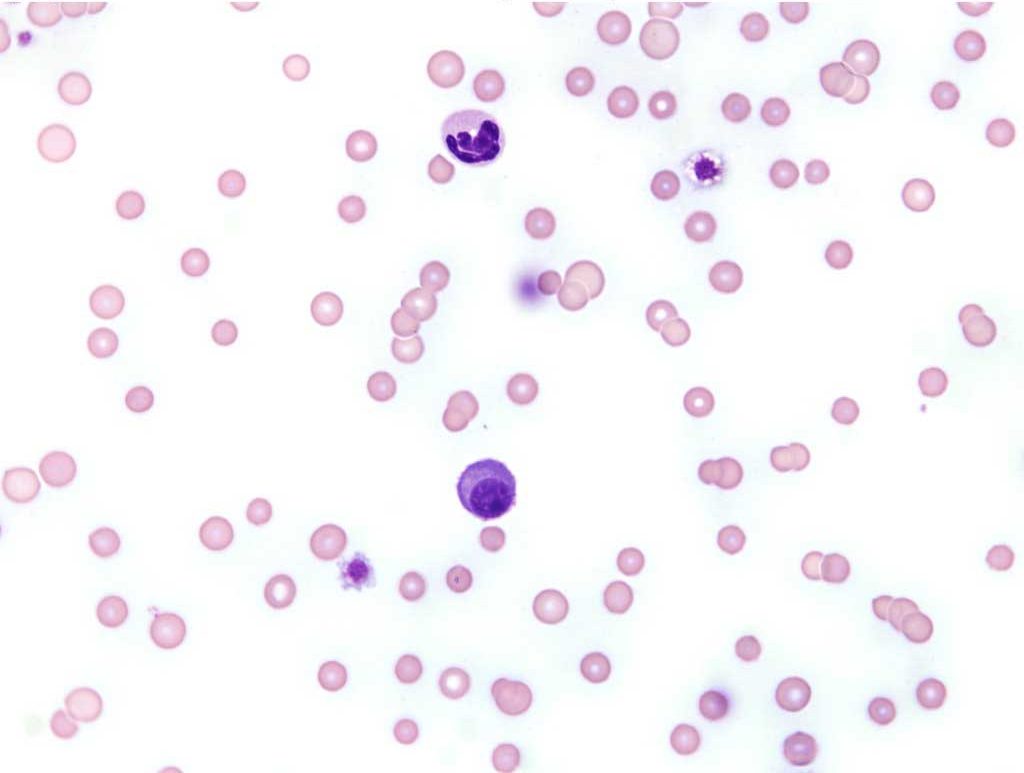

Another form of plasma cell malignancy involves the bone marrow, often resulting in bone lysis and production of a monoclonal gammopathy. Although called plasma cell sarcoma in this chapter, many veterinary authors use the terms plasma cell myeloma and multiple myeloma, which originate from the human literature. Plasma cell leukemia occurs when malignant plasma cells are released into the peripheral blood (Fig. 3.6). Often the plasma cell numbers are not extremely high and examination of a buffy coat preparation may reveal the malignant cells which could otherwise be overlooked on examination of a direct blood smear. Bone marrow involvement may be diffuse or focal. If the tumor is diffuse, bone marrow aspiration from any site will reveal the neoplastic process. If the tumor is focal or multifocal, aspiration from a lytic or painful area is more likely to yield neoplastic cells. Involvement of lymph nodes, kidneys, liver and spleen may occur, either as metastatic sites or as additional primary sites of the multicentric tumor. IL-1 and other soluble mediators with bone resorptive activity represent osteoclast activating factors that are elaborated by the neoplastic cells and may lead to bone lysis and hypercalcemia. The first clinical sign may be lameness in cases where osteolysis is occurring, particularly if weight-bearing bones are affected.

When the malignant clone of plasma cells uncontrollably produces an abnormal immunoglobulin, the serum protein may be very high and a mono or biclonal gammopathy noted on serum protein electrophoresis. The immunoglobulin is usually characterized as IgG or IgA, and less commonly, IgM, on immunoelectrophoresis. High levels of immunoglobulins in the serum can lead to hyperviscosity, impaired platelet function, and increased rouleaux formation on peripheral blood smears. Bleeding, central nervous signs, and organ failure can result from the hyperviscosity. If immunoglobulin light chains are produced by the neoplastic cells, these can be filtered by the kidney and appear in the urine where they are known as Bence Jones proteins. These are best detected by immunoelectrophoresis of the urine. Great care must be taken when using rigid criteria to diagnose plasma cell sarcoma since sometimes non-neoplastic disorders can result in markedly increased numbers of plasma cells in the bone marrow and monoclonal gammopathy. Chronic infections with agents such as dimorphic fungi, Ehrlichia, and feline infectious peritonitis can occasionally result in changes which mimic plasma cell sarcomas. A diagnosis of plasma cell sarcoma may be made if a minimum of 2 of the following 4 criteria are met: osteolysis; plasma cells comprising >20% of bone marrow cells (possibly changing to >10% in cats); monoclonal gammopathy; Bence Jones proteinuria. However, all of the historical, clinical, physical, and laboratory findings must be used collectively in diagnosing this disease.

Focal/solitary mass of neoplastic plasma cells that can be in soft tissues or bone, called extramedullary plasmacytoma (EMP) or solitary osseous plasmacytoma (SOP), respectively.

Variation in morphology.

Variation in cell size.

Variation in nuclear size.

Gammopathy characterized by a single narrow-based peak or spike in the gamma region, often reflecting a clonal neoplastic production of immunoglobulin.

The buff-colored layer, containing leukocytes and platelets, that separates red blood cells from plasma when peripheral blood is centrifuged.

Gammopathy characterized by 2 narrow-based peaks in the gamma region, often reflecting a clonal neoplastic production of immunoglobulin.

Technique for separating and quantitating proteins in fluids, e.g. serum or urine.

Thickening or sludging of the blood due to high concentrations of immunoglobulin or absolute erythrocytosis.

An anucleate (in mammalian species) cytoplasmic fragment arising from a megakaryocyte; vital for primary hemostasis.

“Stack” of red blood cells resembling a roll of coins; prominent in equine and often feline blood. Formation increases as negative charges between RBCs decrease (e.g. with increased plasma proteins).

Immunoglobulin light chains present in the urine; associated with malignant plasma cell tumor (plasma cell sarcoma).

Malignant neoplasm of mesenchymal origin, e.g. osteosarcoma.