Gastrointestinal Tract

Overview

There are numerous diseases of the gastrointestinal tract that may cause a variety of clinicopathological abnormalities. Diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration, weight loss, lethargy, and melena may all be associated with small bowel disease. Certain features may allow distinction between small-bowel and large-bowel diarrhea. Small-bowel diarrhea is characterized by large volume feces whereas large-bowel diarrhea produces small volume feces, often associated with mucus, increased frequency, and tenesmus. Some of the more common diseases are discussed in this chapter as well as in Chapter 6: Body Water, Electrolytes, and Acid-Base Balance.

Malabsorption

Malabsorption is a failure of the intestine to absorb digested nutrients and can be caused by a variety of small intestinal lesions due to inflammatory, infectious and/or neoplastic processes. Malabsorption differs from maldigestion, which is a failure to adequately digest food and usually results from atrophy of exocrine pancreatic acinar cells causing inadequate secretion of digestive enzymes as described earlier (see EPI).

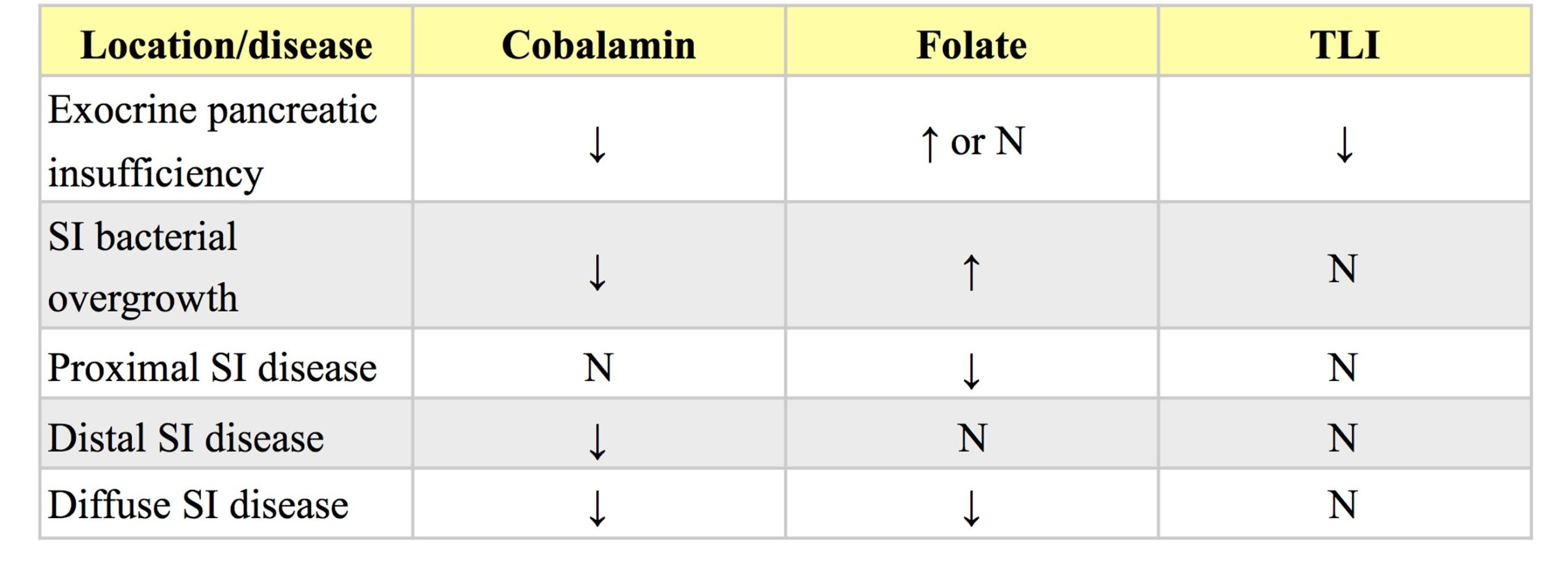

Cobalamin and folate

Many clinicians request cobalamin (vitamin B12) and folate on the same serum sample submitted for TLI, with the purpose of localizing the site(s) of malabsorption should maldigestion be ruled out (Table 9.1). Also, abnormalities in serum cobalamin and folate can occur secondary to long-standing EPI, and cobalamin supplementation as well as pancreatic enzyme supplementation may be necessary to successfully treat the disease. Low cobalamin concentrations can occur with lack of secretion of bicarbonate-rich fluid from the pancreas into the duodenum, therefore, EPI should be ruled out before interpreting low cobalamin concentrations. Lack of intrinsic factor (IF) can occur in cats with EPI as it is produced only by pancreatic cells in cats whereas in dogs IF is produced by both pancreatic acinar and gastric mucosal cells. IF is required for binding of cobalamin within the small intestine where the complex is carried to the ileum and binds to specific receptors facilitating entrance into enterocytes. Therefore decreased IF leads to less cobalamin/IF complex formation and less cobalamin absorption. Overgrowth of bacteria (especially anaerobes) in the duodenum results in increased binding of cobalamin and decreased cobalamin absorption. Ileal mucosal pathology can result in decreased cobalamin absorption, as can an inherited deficiency of the receptor for the IF/cobalamin complex which has been documented in Giant Schnauzer and Border Collie dogs. Cobalamin malabsorption in these dogs causes hematologic changes such as nonregenerative anemia with occasional megaloblasts and neutropenia with occasional hypersegmentation of neutrophils.Increased serum folate concentrations can occur due to bacterial production of folate in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, increased acidity in the intestinal tract as occurs with EPI and increased gastric acid secretion, and increased dietary folate intake. Decreased concentrations of serum folate can occur with absorptive diseases of the proximal small intestine.

Other laboratory findings

In addition to changes in serum cobalamin and folate concentrations, hypocholesterolemia, hypoglycemia, and hypocalcemia may accompany malabsorption, but are nonspecific and inconsistent laboratory findings. Several other tests are or have been available to assess intestinal absorption and digestion. However, if maldigestion has been ruled out (in dogs and cats for which there is a reliable assay), often endoscopy, quantitative bacterial cultures of intestinal contents, and biopsies are indicated in order to determine the cause of malabsorption. The glucose absorption test is sometimes used to assess intestinal absorption in horses and has largely replaced the xylose absorption test. The xylose absorption test has several disadvantages including expense, availability of xylose and the assay by which it is measured. Glucose absorption tests can be used to assess intestinal absorption in small animals (though rarely used) and preruminant calves, but cannot be used in adult ruminants as sugars are degraded in the rumen.

Protein losing enteropathy (PLE)

Several inflammatory and neoplastic bowel diseases, as well as lymphangiectasia, can result in protein loss into the intestinal lumen. Signs such as vomiting, diarrhea, and weight loss are inconsistently present. Edema and ascites occur when the serum albumin concentration approaches 10 g/L (1 g/dL). Thromboembolism can result from concurrent losses of antithrombin. Diffuse rather than localized intestinal disease is more likely to result in significant protein loss and detection of hypoproteinemia on serum biochemical analysis. Normally albumin and globulins are both lost to the same degree with PLE. Occasionally globulins are within the RI or increased due to antigenic stimulation and increased production of immunoglobulins. The other main differentials for hypoproteinemia or hypoalbuminemia (protein-losing nephropathy, hepatic dysfunction, and exudation from the skin) should be ruled out through complete history taking, thorough physical examination, and laboratory testing including urinalysis (possibly including UPC), and serum bile acids.

Species-specific assays to detect α1-proteinase inhibitor (α1-PI) have been developed for the cat and dog. α1-PI, which is similar in size to albumin, inhibits proteinases such as trypsin. When albumin is lost into the intestinal tract, α1-PI is excreted undegraded in the feces. Concentrations of α1-PI can be measured in fecal extracts as this substance is not normally present in the intestinal lumen. The test is reportedly useful in detecting excessive intestinal protein loss prior to detectable decreases in serum proteins. An assay for canine serum α1-PI has been validated and a RI established, although the test is not yet available commercially. The serum concentration is expected to be low in dogs with gastrointestinal disease causing PLE and may be more convenient than the fecal test.

Ultimately, endoscopy or laparotomy and intestinal biopsies are usually required to determine the etiology of PLE. Infiltrative bowel disease (including neoplasia), diffuse enteric bacterial, fungal or parasitic diseases, and lymphatic disorders are frequent causes of PLE.

Intestinal hemorrhage

There are several causes, both acute and chronic, of intestinal hemorrhage. Whether or not blood is visible in the feces will depend on the volume, the rapidity, and the site(s) of blood loss. A fecal occult blood test can be performed on the feces if intestinal blood loss is suspected, but not visible. The test is very sensitive and can yield false positive results due to the presence of myoglobin or plant peroxidases. Meat diets (including commercial pet food) should be withdrawn for 72 hours prior to testing. Chronic intestinal blood loss eventually causes iron deficiency anemia. Advanced iron deficiency is manifested as microcytic, hypochromic anemia with variable degrees of regeneration. Moderate regeneration and microcytosis, with or without hypochromia, are generally present in the earlier stages when the condition is often detected. The species, age, history, clinical findings, and other laboratory findings will help focus the investigation to determine the cause. For example, abomasal ulceration would be a differential in cattle. An older dog with weight loss and chronic intestinal blood loss should be investigated for the presence of an intestinal tumor. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug administration should be ruled out as a potential cause prior to pursuing other etiologies. Thrombocytopenia and platelet function defects, if chronic, could be responsible for significant intestinal blood loss. However, one would expect bleeding from other superficial surfaces as well. Depending on the geographic location, blood-sucking intestinal parasites may be a consideration.

Gastritis/gastroenteritis

Laboratory changes seen with gastritis or gastroenteritis vary with the etiology of the inflammation. Salmonellosis typically produces severe inflammation and secretory diarrhea. The leukogram may reflect a degenerative left shift, and blood and protein are often lost into the intestinal tract. Normally blood loss is associated with anemia and hypoproteinemia, but these may be masked by volume contraction. With restoration of fluid balance anemia and hypoproteinemia may be revealed.

Canine hemorrhagic gastroenteritis

A poorly understood disorder in dogs, known as hemorrhagic gastroenteritis, is associated with acute vomiting and diarrhea. Etiologies which have been considered are clostridial enterotoxemia and type I hypersensitivity reaction. The disease is overrepresented in toy and miniature dogs, especially Miniature Schnauzer and Toy Poodle breeds. The characteristic laboratory finding is an elevated hematocrit, sometimes as high as 0.80 L/L. Severe dehydration may be the explanation for this elevation; however, the plasma/serum protein is not concurrently elevated. Protein loss in the diarrhea could be responsible for the lack of agreement between hematocrit and protein in this disease. Despite the hemorrhagic nature of the diarrhea, perhaps protein is selectively lost or protein is lost prior to onset of blood loss. Normally, one would expect the hematocrit to decrease due to blood loss into the intestinal tract. However, these dogs are usually not clinically dehydrated, and the peracute onset of the disease may preclude equilibration of interstitial and intravascular fluids.

Equine colic

Colic in horses can result in various laboratory changes, depending on the severity, the level of the intestinal tract that is involved, the etiology (e.g. bacterial, parasitic, viral, dietary, neoplastic, traumatic, and others), whether or not the intestinal wall is devitalized, and whether there is gastric reflux, diarrhea, or impaction present. Cytologic examination of abdominal fluid is extremely valuable in prognostication and assessing surgical candidacy of equine colic patients. For example, detection of a degenerative left shift on the leukogram and septic exudate on abdominocentesis would indicate a very poor to grave prognosis. Surgery is often not attempted in these circumstances.

Grain overload

Grain overload or bloat in ruminants results in excessive fermentation of carbohydrate, lactic acid accumulation, and metabolic acidosis with a high anion gap. In severe cases, this leads to chemical rumenitis, sometimes with such severe damage to the rumen mucosa that systemic bacterial or fungal infection occurs. Affected cattle are very ill and in addition to the acid-base disturbance, they often have evidence of severe/overwhelming inflammation on the CBC.

Decrease in hematocrit (PCV) recognized on the complete blood count (CBC); usually hemoglobin concentration and RBC numbers are also decreased.

Decrease in the number of neutrophils in peripheral blood below the reference interval for the species.

Most abundant plasma protein in health; maintains oncotic pressure.

Formed in the liver from cholesterol and excreted into the intestine to aid the digestion of fats. Measurement after a meal can be useful in evaluating hepatic function.

Heme protein responsible for oxygen transport in muscle.

Anemia in which there is insufficient body iron for effective erythropoiesis, usually caused by chronic external blood loss. Anemia remains regenerative until the end-stage of iron deficiency. The anemia is characterized by microcytic hypochromic RBCs.

Increased number of erythrocytes with decreased volume that usually corresponds with decreased MCV; often associated with iron deficiency as well as portosystemic shunts.

Decrease in the number of circulating platelets below the reference interval.

An anucleate (in mammalian species) cytoplasmic fragment arising from a megakaryocyte; vital for primary hemostasis.

Increase in immature neutrophils in which there is no neutrophilia and numbers of mature neutrophils are equal to or less than the numbers of immature stages; suggests the bone marrow is not able to meet peripheral demand.

Exudate containing an infectious/etiologic agent (e.g. bacteria); often containing degenerate neutrophils as well.

Process of obtaining abdominal fluid for cytologic evaluation.

Process that adds acid (H+) to the blood or removes base (HCO3-); blood pH may or may not be decreased.

Difference between unmeasured anion and cation concentrations, calculated using the formula: (Na+ + K+) minus (Cl- + HCO3-.)