Myeloid Neoplasms

For the purposes of this chapter, myeloid neoplasms are defined as including clonal proliferations of erythrocyte, granulocyte (neutrophil, eosinophil, or basophil), monocyte (including histiocyte), megakaryocyte, and mast cell lineages (Fig. 3.7). In humans, myeloid neoplasms are subdivided into acute myeloid neoplasms, myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) (formerly chronic myeloid neoplasms), and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) (Fig. 3.1). Attempts are being made to adopt similar terminology in describing the subcategories of myeloid neoplasms in veterinary medicine, however, universal acceptance and use have not yet occurred. Identification of the neoplastic cell line is not difficult if the cells are well-differentiated. When this is not the case, cytochemical, immunocytochemical, immunohistochemical, flow cytometric and other molecular tests may be required to determine cell type. Treatment and prognosis vary with stage at diagnosis, cell lineage and degree of differentiation, amongst other factors, emphasizing the importance of an accurate diagnosis.

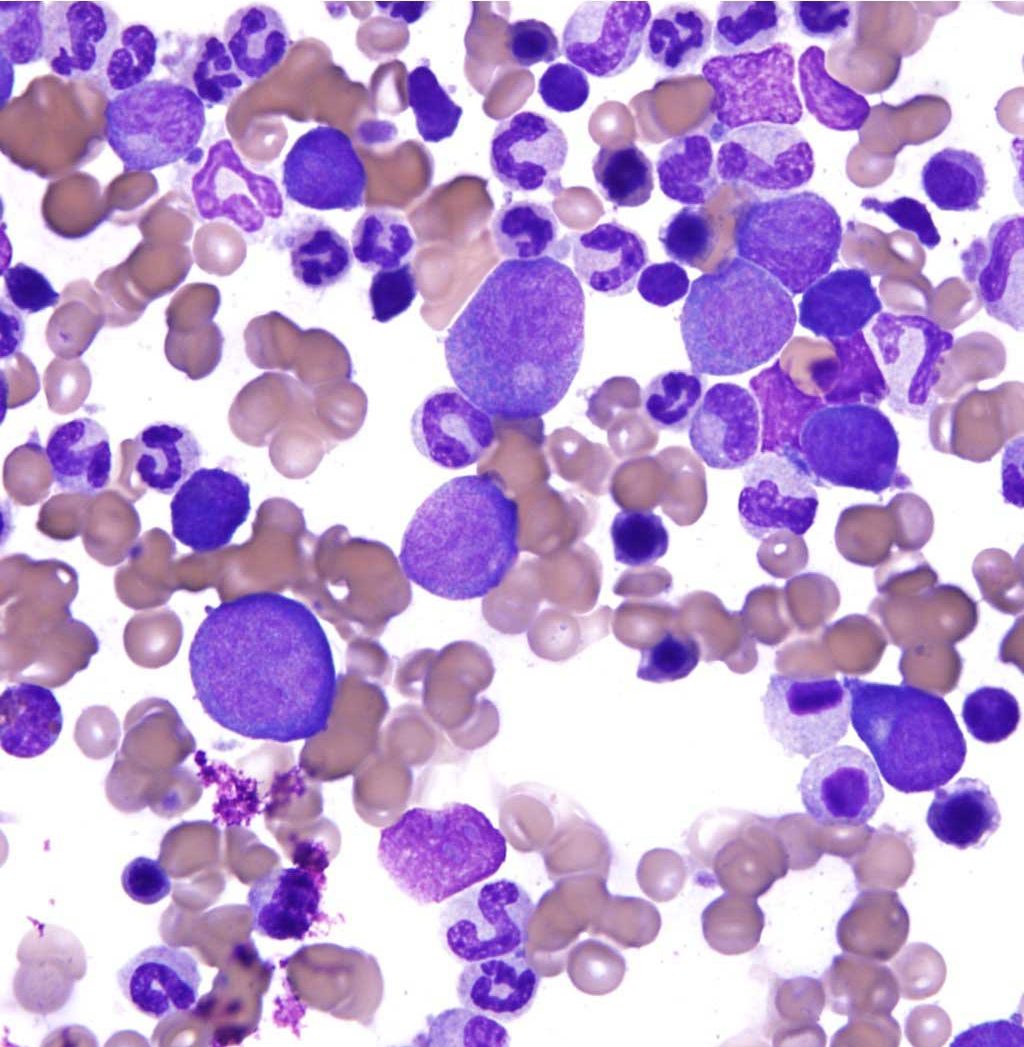

Typically with myeloid neoplasia, the bone marrow is hypercellular and neoplastic cells occupy a considerable portion of the marrow space at the expense of normal tissue. Myeloid neoplasia is most often associated with release of neoplastic cells into the peripheral blood, and may be accompanied by cytopenia(s) of non-neoplastic hemopoietic cell line(s). Morphologic features and numbers of blast cells in bone marrow and peripheral blood are important in determining the subtype; the time frame is less important as it is often unknown. Blast cells are large, immature cells of a certain lineage (e.g. erythroid, granulocytic, monocytic, megakaryocytic), with fine chromatin, one or more nucleoli, and dark staining cytoplasms (Fig. 3.8). The term acute refers to a relatively undifferentiated phenotype, high numbers of blast cells in the bone marrow, and a more rapidly deteriorating clinical course following diagnosis. In contrast, the chronic myeloid neoplasms or MPNs have a more differentiated phenotype, lower numbers of blast cells in the bone marrow, and a more protracted clinical course following diagnosis. Acute neoplasms have blast cells exceeding 30% of all nucleated bone marrow cells, while chronic neoplasms have <30% blasts in the bone marrow. (Note: Although the limit has been decreased to 20% blasts in human medicine, this change has not yet officially occurred in veterinary medicine.) The importance of obtaining good quality bone marrow samples for submission to a reference laboratory and evaluation by an experienced clinical pathologist cannot be overemphasized. Bone marrow should be sampled, not just when hemopoietic neoplasia is suspected, but any time an unexplained hematologic abnormality is identified (see Protocol Manual for complete description of the procedure and sample handling; also see Bone Marrow Aspiration Video).

Red blood cell (RBC); an anucleate (in mammalian species) cell containing hemoglobin needed for oxygen transport. Typically shaped like a bi-concave disk.

Mobile leukocyte with the ability to phagocytose, degrade, and/or kill microorganisms (neutrophil, eosinophil, basophil).

Granulocyte with large, round, pink to orange (eosinophilic) cytoplasmic granules and an often bi-lobed nucleus; important in host response to allergens and defense against parasites.

Granulocyte with variably-sized, dark purple (basophilic) cytoplasmic granules and an irregularly lobulated nucleus; important in hypersensitivity reactions.

Mononuclear phagocytic leukocyte that develops into macrophages in tissue.

Tissue macrophage.

Polyploid cell found in the bone marrow (also spleen and lung) that produces platelets.

Type of non-lymphoid bone marrow derived neoplasm in which there are high numbers of blast cells in the bone marrow, cell lineage may not be obvious based on morphology alone, and the clinical course is often rapidly deteriorating following diagnosis.

A tumor of bone marrow-derived cells, generally chronic myeloid neoplasms

Type of non-lymphoid bone marrow derived neoplasm in which there are lower numbers of blast cells in the bone marrow (compared to the acute form), cell lineage can be determined based on morphology, and the clinical course is protracted following diagnosis.

Abnormal uncontrolled growth of cells that are unresponsive to normal physiologic growth controls; may be benign or malignant.

Immature cell of any hemopoietic cell line, usually containing a nucleolus; may be further described by cell type, e.g. lymphoblast, erythroblast.