Monocytes

Monopoiesis

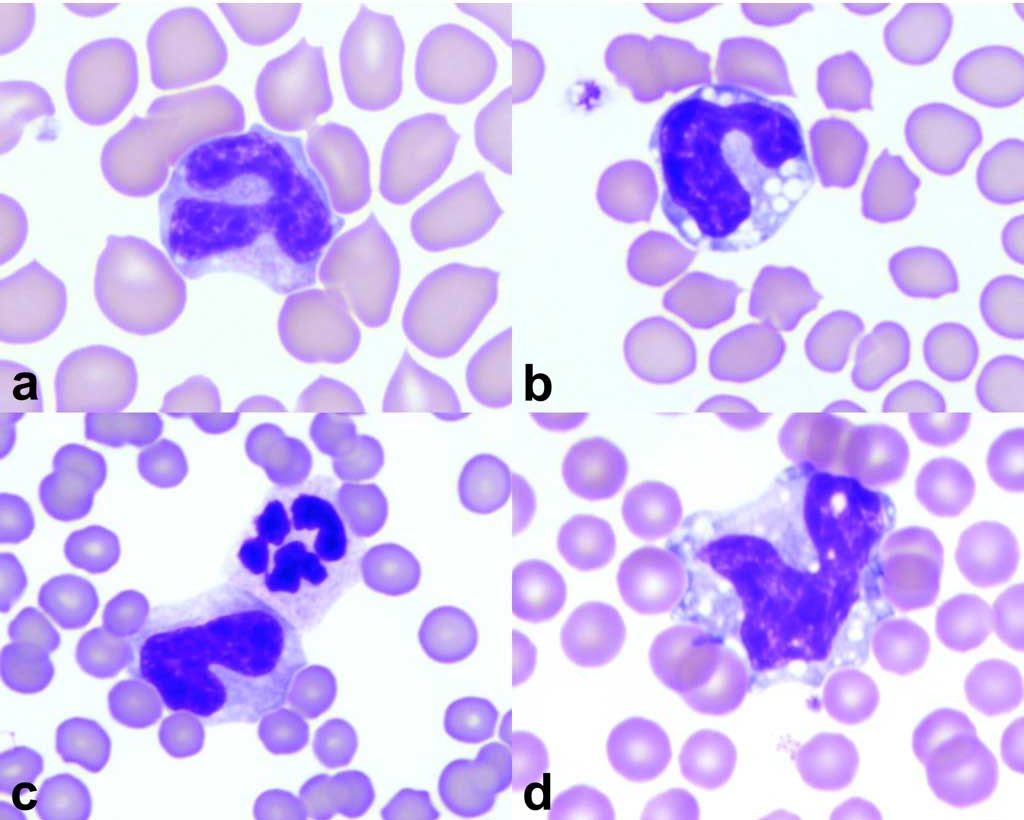

Monocytes are derived in the bone marrow from a precursor common to both neutrophils and monocytes. IL-3, GM-CSF, and M-CSF are the cytokines that influence monocyte development and function. Although monoblasts and promonocytes precede the mature monocyte, these are usually not recognized in bone marrow aspirates, probably because they have no distinguishing features. Monocytes exit the bone marrow within a few hours of maturation and, therefore, a storage pool of promonocytes and monocytes does not exist. Circulating monocytes are usually readily recognized and differentiated from other peripheral blood leukocytes. Monocytes appear larger than most other leukocytes on peripheral blood smears, nuclei are pleomorphic, but usually lobulated, cytoplasms are grey-blue and may contain fine pink granules and vacuoles (Fig. 2.10).

Monocytes undergo transformation to macrophages within tissues. Macrophages residing in tissue sites are long-lived; however, monocytes and macrophages that are recruited to sites of inflammation are relatively short-lived. Tissue macrophages are heterogeneous in morphology, biochemistry, and function reflecting their site of differentiation and local influences, such as growth factors, cytokines, and other inflammatory mediators. Examples of cells known or thought to develop from monocyte/macrophage lineage are Kupffer cells in the liver, dendritic cells (antigen presenting cells) in skin and lymph nodes, osteoclasts in bone, and possibly mesothelial cells lining serosal surfaces and synoviocytes lining joint cavities. Macrophages are recognized within marrow tissue where they fulfill phagocytic roles and by providing a source of iron, they serve as nurse cells for erythropoietic islands.

Monocytosis

Any condition associated with increased demand for phagocytic activity may result in monocytosis. However, the peripheral blood pool of monocytes is small relative to the circulating pool of neutrophils. Monocytes differ from neutrophils in that they take up residence within tissues and are capable of local mitosis. Therefore, significant inflammatory and immune-mediated disorders can occur without marked changes in peripheral blood monocyte numbers. In some species, particularly the dog, endogenous and exogenous corticosteroids increase monocyte numbers. Recovery from neutropenia, as with parvoviral infection, may be signalled by monocytosis prior to return of neutrophil numbers. Inflammatory conditions which are predominated by granuloma formation may be associated with monocytosis, with or without accompanying neutrophilia. Immune-mediated diseases involving overzealous reaction of the body to foreign or self antigens is often associated with monocytosis, possibly due to both accelerated destruction of tissues and cells and increased delivery of antigens to the immune system. Unexplained monocytosis or abnormal monocyte morphology should signal the possibility of neoplastic disease. Reactive monocytosis can also be seen in response to tissue necrosis associated with hypoxic injury, primary inflammatory conditions, or tissue damage within tumor masses.

Monocytopenia

Similar to the situation with eosinophils and basophils, the lower limit of monocyte numbers is zero in many domestic species. Therefore, decreased monocyte production usually cannot be recognized on peripheral blood monocyte counts.

Mononuclear phagocytic leukocyte that develops into macrophages in tissue.

Resident macrophage in the sinuses of the liver.

Cell lining body cavities that may exfoliate into body cavity fluids when there is inflammation or accumulation of excess fluid for other reasons; mesothelial cells can become phagocytic.

Increase in the number of monocytes in peripheral blood.