5 Module 5: Power and Politics

Learning Objectives

- Define and differentiate between government, power, and authority.

- Identify and describe Weber’s three types of authority.

- Explain the difference between direct democracy and representative democracy.

- Describe the dynamic of political demand and political supply in determining the democratic “will of the people.”

- Identify and describe factors of political exception that affect contemporary political life.

- Compare and contrast how functionalists, critical sociologists, and symbolic interactionists view government and politics.

5.0 Introduction to Power and Politics

In one of Max Weber’s last public lectures — “Politics as a Vocation” (1919) — he asked, what is the meaning of political action in the context of a whole way of life? (More accurately, he used the term Lebensführung: what is the meaning of political action in the context of a whole conduct of life, a theme we will return to in the next section). He asked, what is political about political action and what is the place of “the political” in the ongoing conduct of social life?

Until recently we might have been satisfied with an answer that examined how various political institutions and processes function in society: the state, the government, the civil service, the courts, the democratic process, etc. However, in the last few years, among many other examples we could cite, we have seen how the events of the Arab Spring in Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt (2010–2011) put seemingly stable political institutions and processes into question. Through the collective action of ordinary citizens, the long-lasting authoritarian regimes of Ben Ali, Gadhafi, and Mubarak were brought to an end through what some called “revolution.” Not only did the political institutions all of a sudden not function as they had for decades, they were also shown not to be at the center of political action at all. What do we learn about the place of politics in social life from these examples?

Revolutions are often presented as monumental, foundational political events that happen only rarely and historically: the American revolution (1776), the French revolution (1789), the Russian revolution (1917), the Chinese revolution (1949), the Cuban revolution (1959), the Iranian revolution (1979), etc. But the events in North Africa remind us that revolutionary political action is always a possibility, not just a rare political occurrence. Samuel Huntington defines revolution as:

a rapid, fundamental, and violent domestic change in the dominant values and myths of a society, in its political institutions, social structure, leadership, and government activity and policies. Revolutions are thus to be distinguished from insurrections, rebellions, revolts, coups, and wars of independence (Huntington 1968, p. 264).

What is at stake in revolution is also, therefore, the larger question that Max Weber was asking about political action. In a sense, the question of the role of politics in a whole way of life asks how a whole way of life comes into existence in the first place.

How do revolutions occur? In Tunisia, the street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire after his produce cart was confiscated. The injustice of this event provided an emblem for the widespread conditions of poverty, oppression, and humiliation experienced by a majority of the population. In this case, the revolutionary action might be said to have originated in the way that Bouazizi’s act sparked a radicalization in people’s sense of citizenship and power: their internal feelings of individual dignity, rights, and freedom and their capacity to act on them. It was a moment in which, after living through decades of deplorable conditions, people suddenly felt their own power and their own capacity to act. Sociology is interested in studying the conditions of such examples of citizenship and power.

5.1 Power and Authority

The nature of political control — what we will define as power and authority — is an important part of society.

Sociologists have a distinctive approach to studying governmental power and authority that differs from the perspective of political scientists. For the most part, political scientists focus on studying how power is distributed in different types of political systems. They would observe, for example, that the Canadian political system is a constitutional monarchy divided into three distinct branches of government (legislative, executive, and judicial), and might explore how public opinion affects political parties, elections, and the political process in general. Sociologists, however, tend to be more interested in government more generally; that is, the various means and strategies used to direct or conduct the behaviour and actions of others (or of oneself). As Michel Foucault described it, government is the “conduct of conduct,” the way some seek to act upon the conduct of others to change or channel that conduct in a certain direction (Foucault 1982, pp. 220-221).

Government implies that there are relations of power between rulers and ruled, but the context of rule is not limited to the state. Government in this sense is in operation whether the power relationship is between states and citizens, institutions and clients, parents and children, doctors and patients, employers and employees, masters and dogs, or even oneself and oneself. (Think of the training regimes, studying routines, or diets people put themselves through as they seek to change or direct their lives in a particular way). The role of the state and its influence on society (and vice versa) is just one aspect of governmental relationships.

On the other side of governmental power and authority are the various forms of resistance to being ruled. Foucault (1982) argues that without this latitude for resistance or independent action on the part of the one over whom power is exercised, there is no relationship of power or government. There is only a relationship of violence or force. One central question sociological analysis asks therefore is: Why do people obey, especially in situations when it is not in their objective interests to do so? “Why do men fight for their servitude as stubbornly as though it were their salvation?” as Gilles Deleuze once put it (Deleuze and Guattari 1977, p. 29). This entails a more detailed study of what we mean by power.

5.1.1 What Is Power?

For centuries, philosophers, politicians, and social scientists have explored and commented on the nature of power. Pittacus (c. 640–568 BCE) opined, “The measure of a man is what he does with power,” and Lord Acton perhaps more famously asserted, “Power tends to corrupt; absolute power corrupts absolutely” (1887). Indeed, the concept of power can have decidedly negative connotations, and the term itself is difficult to define. There are at least two definitions of power, which we will refer to below as power (1) and power (2).

As we noted above, power relationships refer in general to a kind of strategic relationship between rulers and the ruled: a set of practices by which states seek to govern the life of their citizens, managers seek to control the labour of their workers, parents seek to guide and raise their children, dog owners seek to train their dogs, doctors seek to manage the health of their patients, chess players seek to control the moves of their opponents, individuals seek to keep their own lives in order, etc. Many of these sites of the exercise of power fall outside our normal understanding of power because they do not seem “political” — they do not address fundamental questions or disagreements about a “whole way of life” — and because the relationships between power and resistance in them can be very fluid. There is a give and take between the attempts of the rulers to direct the behaviour of the ruled and the attempts of the ruled to resist those directions. In many cases, it is difficult to see relationships as power relationships at all unless they become fixed or authoritarian. This is because our conventional understanding of power is that one person or one group of people has power over another. In other words, when we think about somebody, some group, or some institution having power over us, we are thinking about a relation of domination.

Max Weber defined power (1) as “the chance of a man or of a number of men to realize their own will in a communal action even against the resistance of others who are participating in the action” (Weber 1919a, p. 180). It is the varying degrees of ability one has to exercise one’s will over others. When these “chances” become structured as forms of domination, the give and take between power and resistance is fixed into more or less permanent hierarchical arrangements. They become institutionalized. As such, power affects more than personal relationships; it shapes larger dynamics like social groups, professional organizations, and governments. Similarly, a government’s power is not necessarily limited to control of its own citizens. A dominant nation, for instance, will often use its clout to influence or support other governments or to seize control of other nation states. Efforts by the Canadian government to wield power in other countries have included joining with other nations to form the Allied forces during World Wars I and II, entering Afghanistan in 2001 with the NATO mission to topple the Taliban regime, and imposing sanctions on the government of Iran in the hopes of constraining its development of nuclear weapons.

Endeavours to gain power and influence do not necessarily lead to domination, violence, exploitation, or abuse. Leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi, for example, commanded powerful movements that affected positive change without military force. Both men organized nonviolent protests to combat corruption and injustice and succeeded in inspiring major reform. They relied on a variety of nonviolent protest strategies such as rallies, sit-ins, marches, petitions, and boycotts.

It is therefore important to retain the distinction between domination and power. Politics and power are not “things” that are the exclusive concern of “the state” or the property of an individual, ruling class, or group. At a more basic level, power (2) is a capacity or ability that each of us has to create and act. As a result, power and politics must also be understood as the collective capacities we have to create and build new forms of community or “commons” (Negri, 2004). Power in this sense is the power we think of when we speak of an ability to do or create something — a potential. It is the way in which we collectively give form to the communities that we live in, whether we understand this at a very local level or a global level. Power establishes the things that we can do and the things that we cannot do.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle’s original notion of politics is the idea of a freedom people grant themselves to rule themselves (Aristotle, 1908). Therefore, power is not in principle domination. It is the give and take we experience in everyday life as we come together to construct a better community — a “good life” as Aristotle put it. When we ask why people obey even when it is not in their best interests, we are asking about the conditions in which power is exercised as domination. Thus the critical task of sociology is to ask how we might free ourselves from the constraints of domination to engage more actively and freely in the creation of community.

[JR: Please insert YouTube video, Eric Liu, (2014) “How to Understand Power” at url https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_Eutci7ack}

5.1.2 Politics and the State

What is politics? What is political? The words politics and political refer back to the ancient Greek polis or city-state. For the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BCE), the polis was the ideal political form that collective life took. Political life was life oriented toward the “good life” or toward the collective achievement of noble qualities. The term “politics” referred simply to matters of concern to the running of the polis. Behind Aristotle’s idea of the polis is the concept of an autonomous, self-contained community in which people rule themselves. The people of the polis take it upon themselves to collectively create a way of living together that is conducive to the achievement of human aspirations and good life. Politics (1) is the means by which form is given to the life of a people. The individuals give themselves the responsibility to create the conditions in which the good life can be achieved. For Aristotle, this meant that there was an ideal size for a polis, which he defined as the number of people that could be taken in in a single glance (Aristotle 1908). The city-state was for him therefore the ideal form for political life in ancient Greece.

Today we think of the nation-state as the form of modern political life. A nation-state is a political unit whose boundaries are co-extensive with a society, that is, with a cultural, linguistic or ethnic nation. Politics is the sphere of activity involved in running the state. As Max Weber defines it, politics (2) is the activity of “striving to share power or striving to influence the distribution of power, either among states or among groups within a state” (Weber 1919b, p. 78). This might be too narrow a way to think about politics, however, because it often makes it appear that politics is something that only happens far away in “the state.” It is a way of giving form to politics that takes control out of the hands of people.

In fact, the modern nation-state is a relatively recent political form. Foraging societies had no formal state institution, and prior to the modern age, feudal Europe was divided into a confused patchwork of small overlapping jurisdictions. Feudal secular authority was often at odds with religious authority. It was not until the Peace of Westphalia (1648) at the end of the Thirty Years War that the modern nation-state system can be said to have come into existence. Even then, Germany, for example, did not become a unified state until 1871. Prior to 1867, most of the colonized territory that became Canada was owned by one of the earliest corporations: the Hudson’s Bay Company. It was not governed by a state at all. If politics is the means by which form is given to the life of a people, then it is clear that this is a type of activity that has varied throughout history. Politics is not exclusively about the state or a property of the state. The question is, Why do we come to think that it is?

The modern state is based on the principle of sovereignty and the sovereign state system. Sovereignty is the political form in which a single, central “sovereign” or supreme lawmaking authority governs within a clearly demarcated territory. The sovereign state system is the structure by which the world is divided up into separate and indivisible sovereign territories. At present there are 193 member states in the United Nations (United Nations 2013). The entire globe is thereby divided up into separate states except for the oceans and Antarctica.

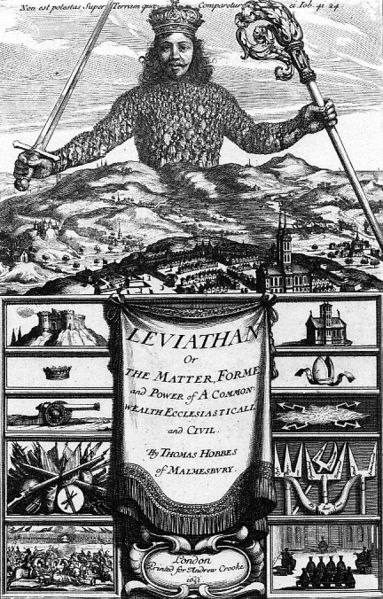

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) is the early modern English political philosopher whose Leviathan (1651) established modern thought on the nature of sovereignty. Hobbes argued that social order, or what we would call today “society” (“peaceable, sociable and comfortable living” (Hobbes 1651, p.146), depended on an unspoken contract between the citizens and the “sovereign” or ruler. In this contract, individuals give up their natural rights to use violence to protect themselves and further their interests and cede them to a sovereign. In exchange, the sovereign provides law and security for all (i.e., for the “commonwealth”). For Hobbes, there could be no society in the absence of a sovereign power that stands above individuals to “over-awe them all” (1651, p. 112). Life would otherwise be in a “state of nature” or a state of “war of everyone against everyone” (1651, p. 117). People would live in “continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man [would be] solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (1651, p. 113).

It is worthwhile to examine these premises, however, because they continue to structure our contemporary political life even if the absolute rule of monarchs has been replaced by the democratic rule of the people. (An absolute monarchy is a government wherein a monarch has absolute or unmitigated power.) The implication of Hobbes’s analysis is that the people must acquiesce to the absolute power of a single sovereign or sovereign assembly, which, in turn, cannot ultimately be held to any standard of justice or morality outside of its own guarantee of order. Therefore, democracy always exists in a state of tension with the authority of the sovereign state. Similarly, while order is maintained by “the sovereign” within the sovereign state, outside the state or between states there is no sovereign to over-awe them all. The international sovereign state system is always potentially in a state of war of all against all. It offered a neat solution to the problem of confused and overlapping political jurisdictions in medieval Europe, but is itself inherently unstable.

Hobbes’ definition of sovereignty is also the context of Max Weber’s definition of the state. Weber defines the state, not as an institution or decision-making body, but as “a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory” (Weber 1919b, p. 78). Weber’s definition emphasizes the way in which the state is founded on the control of territory through the use of force. In his lecture “Politics as a Vocation,” he argues, “The decisive means for politics is violence” (Weber 1919b, p. 121). However, as we have seen above, power is not always exercised through the use of force. Nor would a modern sociologist accept that it is conferred through a mysterious “contract” with the sovereign, as Hobbes argued. Therefore, why do people submit to rule? “When and why do men obey?” (Weber 1919b), p. 78). Weber’s answer is based on a distinction between the concepts of power and authority.

Prior to examining Weber’s insights into the relationship of power and and different types of authority, it is instructive to take a moment to reflect on the historical evolution of governance in Canada.

5.1.3 Types of Authority

The protesters in Tunisia and the civil rights protesters of Mahatma Gandhi’s day had influence apart from their position in a government. Their influence came, in part, from their ability to advocate for what many people held as important values. Government leaders might have this kind of influence as well, but they also have the advantage of wielding power associated with their position in the government. As this example indicates, there is more than one type of authority in a community.

If Weber defined power as the ability to achieve desired ends despite the resistance of others (Weber, 1919a, p. 180), authority is when power or domination is perceived to be legitimate or justified rather than coercive. Authority refers to accepted power — that is, power that people agree to follow. People listen to authority figures because they feel that these individuals are worthy of respect. Generally speaking, people perceive the objectives and demands of an authority figure as reasonable and beneficial, or true.

A citizen’s interaction with a police officer is a good example of how people react to authority in everyday life. For instance, a person who sees the flashing red and blue lights of a police car in his or her rearview mirror usually pulls to the side of the road without hesitation. Such a driver most likely assumes that the police officer behind him serves as a legitimate source of authority and has the right to pull him over. As part of the officer’s official duties, he or she has the power to issue a speeding ticket if the driver was driving too fast. If the same officer, however, were to command the driver to follow the police car home and mow his or her lawn, the driver would likely protest that the officer does not have the authority to make such a request.

Not all authority figures are police officers or elected officials or government authorities. Besides formal offices, authority can arise from tradition and personal qualities. Max Weber realized this when he examined individual action as it relates to authority, as well as large-scale structures of authority and how they relate to a society’s economy. Based on this work, Weber developed a classification system for authority. His three types of authority are traditional authority, charismatic authority, and rational-legal authority (Weber 1922).

| Traditional | Charismatic | Rational-Legal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source of authority | Legitimized by long-standing custom | Based on a leader’s personal qualities | Authority resides in the office, not the person |

| Authority Figure/Figures | Patriarch | Dynamic personality | Bureaucratic officials |

| Examples | Patrimonialism (traditional positions of authority) | Jesus Christ, Hitler, Martin Luther King, Jr., Pierre Trudeau | Parliament, Civil Service, Judiciary |

Traditional authority is usually understood in the context of pre-modern power relationships. According to Weber, the power of traditional authority is accepted because that has traditionally been the case; its legitimacy exists because it has been accepted for a long time. People obey their lord or the church because it is customary to do so. The authority of the aristocracy or the church is conferred on them through tradition, or the “authority of the ‘eternal yesterday’” (Weber 1919b, p. 78). Britain’s Queen Elizabeth, for instance, occupies a position that she inherited based on the traditional rules of succession for the monarchy, a form of government in which a single person, or monarch, rules until that individual dies or abdicates the throne. People adhere to traditional authority because they are invested in the past and feel obligated to perpetuate it. However, in modern society it would also be fair to say that obedience is in large part a function of a customary or “habitual orientation to conform,” in that people do not generally question or think about the power relationships in which they participate.

For Weber though, modern authority is better understood to oscillate between the latter two types of legitimacy: rational-legal and charismatic authority. On one hand, as he puts it, “organized domination” relies on “continuous administration” (1919, p. 80) and in particular, the rule-bound form of administration known as bureaucracy. Power made legitimate by laws, written rules, and regulations is termed rational-legal authority. In this type of authority, power is vested in a particular system, not in the person implementing the system. However irritating bureaucracy might be, we generally accept its legitimacy because we have the expectation that its processes are conducted in a neutral, disinterested fashion, according to explicit, written rules and laws. Rational-legal types of rule have authority because they are rational; that is, they are unbiased, predictable, and efficient.

On the other hand, people also obey because of the charismatic personal qualities of a leader. In this respect, it is not so much a question of obeying as following. Weber saw charismatic leadership as a kind of antidote to the machine-like rationality of bureaucratic mechanisms. It was through the inspiration of a charismatic leader that people found something to believe in, and thereby change could be introduced into the system of continuous bureaucratic administration. The power of charismatic authority is accepted because followers are drawn to the leader’s personality. The appeal of a charismatic leader can be extraordinary, inspiring followers to make unusual sacrifices or to persevere in the midst of great hardship and persecution. Charismatic leaders usually emerge in times of crisis and offer innovative or radical solutions. They also tend to hold power for short durations only because power based on charisma is fickle and unstable.

Of course the combination of the administrative power of rational-legal forms of domination and charisma have proven to be extremely dangerous, as the rise to power of Adolf Hitler shortly after Weber’s death demonstrated. We might also point to the distortions that a valuing of charisma introduces into the contemporary political process. There is increasing emphasis on the need to create a public “image” for leaders in electoral campaigns, both by “tweaking” or manufacturing the personal qualities of political candidates — Stephen Harper’s sudden propensity for knitted sweaters, Jean Chretian’s “little guy from Shawinigan” persona, Jack Layton’s moustache — and by character assassinations through the use of negative advertising — Stockwell Day’s “scary, narrow-minded fundamentalist” characterization, Paul Martin’s “Mr. Dithers” persona, Michael Ignatieff’s “the fly-in foreign academic” tag, Justin Trudeau’s “cute little puppy” moniker. Image management, or the attempt to manage the impact of one’s image or impression on others, is all about attempting to manipulate the qualities that Weber called charisma. However, while people often decry the lack of rational debate about the facts of policy decisions in image politics, it is often the case that it is only the political theatre of personality clashes and charisma that draws people in to participate in political life.

5.1.4 Politics and the Image

Politicians, political parties, and other political actors are also motivated to claim symbolic meanings for themselves or their issues. A Canadian Taxpayer Federation report noted that the amount of money spent on communication staff (or “spin doctors”) by the government in 2014 approached the amount spent on the total House of Commons payroll ($263 million compared to $329 million per year) (Thomas, 2014). While most sectors of the civil service have been cut back, “information services” have continued to expand.

This practice of calculated symbolization through which political actors attempt to control or manipulate the impressions they make on the public is known as image management or image branding. Erving Goffman (1972) described the basic processes of image management in the context of small scale, face-to-face settings. In social encounters, he argued, individuals present a certain “face” to the group — “this is who I am” — by which they lay claim to a “positive social value” for themselves. It is by no means certain that the group will accept the face the individual puts forward, however. Individuals are therefore obliged during the course of interactions to continuously manage the impression they make in light of the responses, or potential responses of others — making it consistent with the “line” they are acting out. They continually make adjustments to cover over inconsistencies, incidents, or gaffs in their performance and use various props like clothing, hair styles, hand gestures, demeanour, forms of language, etc. to support their claim. The key point that Goffman makes is that one’s identity, face, or impression is not something intrinsic to the individual but is a social phenomenon, radically in the hands of others. The “presentation of self in everyday life” is a tricky and uncertain business.

On the political stage, especially in the age of mass-mediated interactions, image management and party branding are subject to sophisticated controls, calculations, and communications strategies. In effect, political image management is the process by which concrete, living historical events and processes — what politicians actually say and do in the public sphere day-to-day, how government policies are implemented, and what their effects on stakeholders and social processes are — are turned into ahistorical, “mythic” events and qualities: heroic struggles of good versus evil, prudence versus wastefulness, change and renewal versus stagnation and decline, or archetypal symbolic qualities of personal integrity, morality, decisiveness, toughness, feistiness, wisdom, tenacity, etc. Politicians and political parties claim a “positive social value” for themselves by attempting to plant a symbolic, mythic image in the minds of the public and then carefully scripting public performances to support that image. As Goffman points out with respect to face-to-face interactions, however, it is by no means certain that the public or the news media will accept these claims. The Canadian Alliance leader Stockwell Day’s Jet Ski photo op during the 2000 federal election undermined his credibility as potential prime ministerial material, just as Progressive Conservative leader Robert Stanfield’s football fumble on the airport tarmac in the 1974 federal election undermined his bid to appear more youthful (Smith, 2012).

Critics point to the way the focus on image in politics replaces political substance with superficial style. Using image to present a political message is seen as a lower, even fraudulent form of political rhetoric. Symbolic interactionists (discussed below) would note however that the ability to attribute persuasive meaning to political claims is a communicative process that operates at multiple levels. Determining what is and what is not a “substantial” issue is in fact a crucial component of political communication. Deluca (1999) argues that as a result of being locked out of the process of political communication, groups like environmental social movements can effectively bring marginalized issues into the public debate by staging image events. In the language of Greenpeace founder Robert Hunter, these are events that take the form of powerful visual imagery. They explode “in the public’s consciousness to transform the way people view their world” (cited in Deluca, 1999, p. 1). Greenpeace’s use of small inflatable Zodiac boats to get between whaling vessels and whales is one prominent example of an image event that creates a visceral effect in the audience.

Commenting on singer-songwriter Neil Young’s 2014 “Honour the Treaties” tour in Canada, Gill notes that the effectiveness of this type of image event is in the emotional resonance it establishes between the general public and aboriginal groups fighting tar sands development. “Plainly put, our governments don’t fear environmentalists, even icons like David Suzuki. But governments fear emotion, which they can’t regulate, and who but our artists are capable of stirring our emotions, giving them expression, and releasing the trapped energy in our national psyche?” (Gill, 2014). So, do image politics, image management, and image events necessarily make democratic will formation less substantial and less issues oriented? As Deluca puts it, “To dismiss image events as rude and crude is to cling to ‘presuppositions of civility and rationality underlying the old rhetoric,’ a rhetoric that supports those in positions of authority and thus allows civility and decorum to serve as masks for the protection of privilege and the silencing of protest (Deluca, 1999, pp. 14-15).

5.2 Democratic Will Formation

Most people presume that anarchy, or the absence of organized government, does not facilitate a desirable living environment for society. They have in the back of their minds the Hobbesian view that the absence of sovereign rule leads to a state of chaos, lawlessness, and war of all against all. However, anarchy literally means “without leader or ruler.” Anarchism therefore refers to the political principles and practice of organizing social life without formal or state leadership. As such, the radical standpoint of anarchism provides a useful standpoint from which to examine the sociological question of why leadership in the form of the state is needed in the first place. We will return to this question in the final section of this module.

The tradition of anarchism developed in Europe in the 19th century in the work of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865), Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876), Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921) and others. It promoted the idea that states were both artificial and malevolent constructs, unnecessary for human social organization (Esenwein 2004). Anarchists proposed that the natural state of society is one of self-governing collectivities, in which people freely group themselves in loose affiliations with one another rather than submitting to government-based or human-made laws. They had in mind the way rural farmers came together to organize farmers’ markets or the cooperative associations of Swiss watchmakers in the Jura mountains. For the anarchists, anarchy was not violent chaos but the cooperative, egalitarian society that would emerge when state power was destroyed.

The anarchist program was (and still is) to maximize the personal freedoms of individuals by organizing society on the basis of voluntary social arrangements. These arrangements would be subject to continual renegotiation. As opposed to right-wing libertarianism, the anarchist tradition argued that the conditions for a cooperative, egalitarian society were the destruction of both the power of the state and of private property (i.e., capital). One of Proudhon’s famous anarchist slogans was “Private property is theft!” (Proudhon 1840).

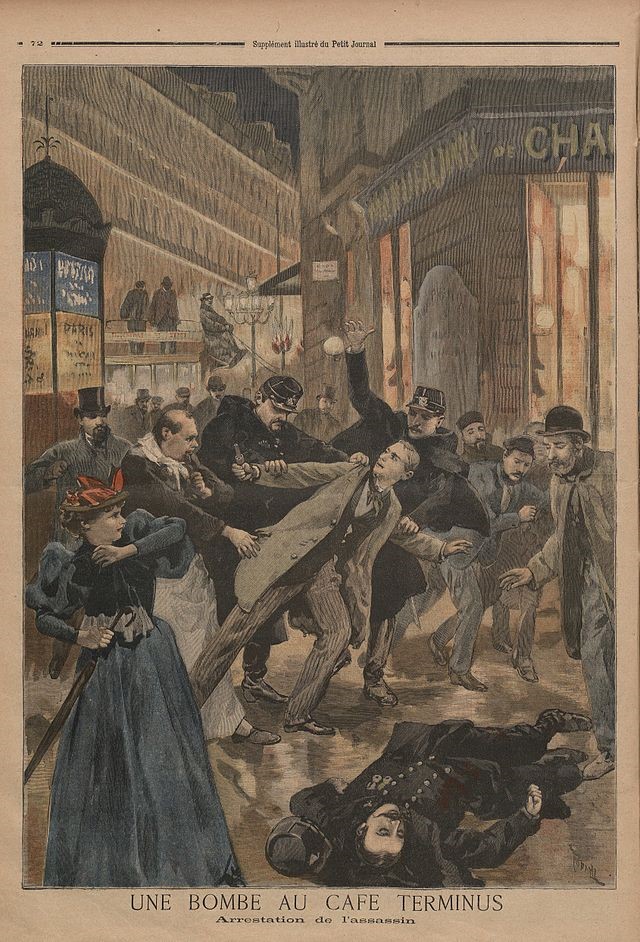

In practice, 19th century anarchism had the dubious distinction of inventing modern political terrorism, or the use of violence on civilian populations and institutions to achieve political ends (CBC Radio 2011). This was referred to by Mikhail Bakunin as “propaganda by the deed” (1870). Clearly not all or even most anarchists advocated violence in this manner, but it was widely recognized that the hierarchical structures and institutions of the old society had to be destroyed before the new society could be created.

Nevertheless, the principle of the anarchist model of government is based on the participatory or direct democracy of the ancient Greek Athenians. In Athenian direct democracy, decision making, even in matters of detailed policy, was conducted through assemblies made up of all citizens. These assemblies would meet a minimum of 40 times a year (Forrest 1966). The root of the word democracy is demos, Greek for “people.” Democracy is therefore rule by the people. Ordinary Athenians directly ran the affairs of Athens. (Of course “all citizens,” for the Greeks, meant all adult men and excluded women, children, and slaves.)

Direct democracy can be contrasted with modern forms of representative democracy, like that practised in Canada. In representative democracy, citizens elect representatives (MPs, MLAs, city councillors, etc.) to promote policies that favour their interests rather than directly participating in decision making themselves. It is based on the idea of representation rather than direct citizen participation. Critics note that the representative model of democracy enables distortions to be introduced into the determination of the will of the people: elected representatives are typically not socially representative of their constituencies as they are dominated by white men and elite occupations like law and business; corporate media ownership and privately funded advertisement campaigns enable the interests of privileged classes to be expressed rather than those of average citizens; and lobbying and private campaign contributions provide access to representatives and decision-making processes that is not afforded to the majority of the population. The distortions that intrude into the processes of representative democracy — for example, whose interests really get represented in government policy? — are no doubt behind the famous comment of the former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill who once declared to the House of Commons, “Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government … except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time” (Shapiro 2006).

Democracy however is not a static political form. Three key elements constitute democracy as a dynamic system: the institutions of democracy (parliament, elections, constitutions, rule of law, etc.), citizenship (the internalized sense of individual dignity, rights, and freedom that accompanies formal membership in the political community), and the public sphere (or open “space” for public debate and deliberation). On the basis of these three elements, rule by the people can be exercised through a process of democratic will formation.

Jürgen Habermas (1998) emphasizes that democratic will formation in both direct and representative democracy is reached through a deliberative process. The general will or decisions of the people emerge through the mutual interaction of citizens in the public sphere. The underlying norm of the democratic process is what Habermas (1990) calls the ideal speech situation. An ideal speech situation is one in which every individual is permitted to take part in public discussion equally: to question assertions and introduce ideas. Ideally no individual is prevented from speaking (not by arbitrary restrictions on who is permitted to speak, nor by practical restrictions on participation like poverty or lack of education). To the degree that everyone accepts this norm of openness and inclusion, in free debate the best ideas will “rise to the top” and be accepted by the majority. On the other hand, when the norms of the ideal speech situation are violated, the process of democratic will formation becomes distorted and open to manipulation.

5.2.1 Political Demand and Political Supply

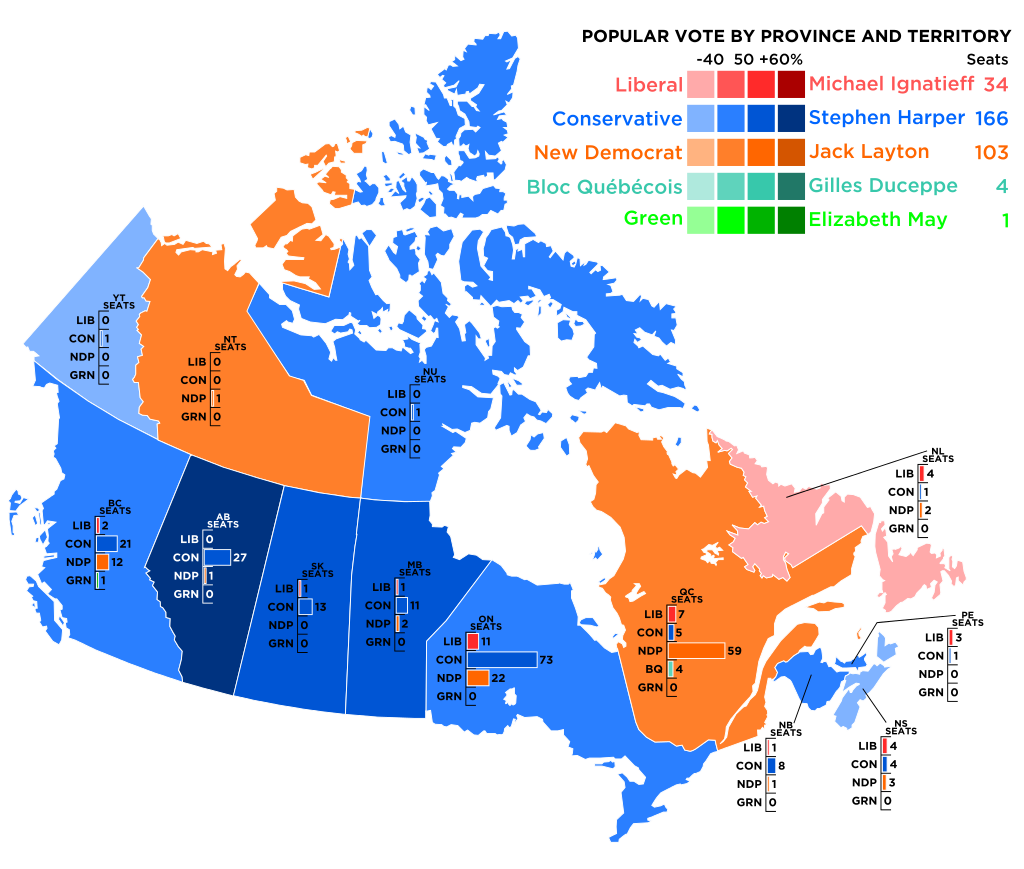

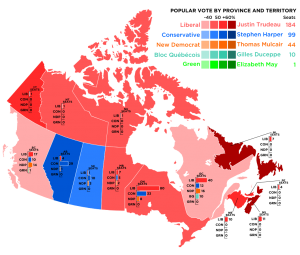

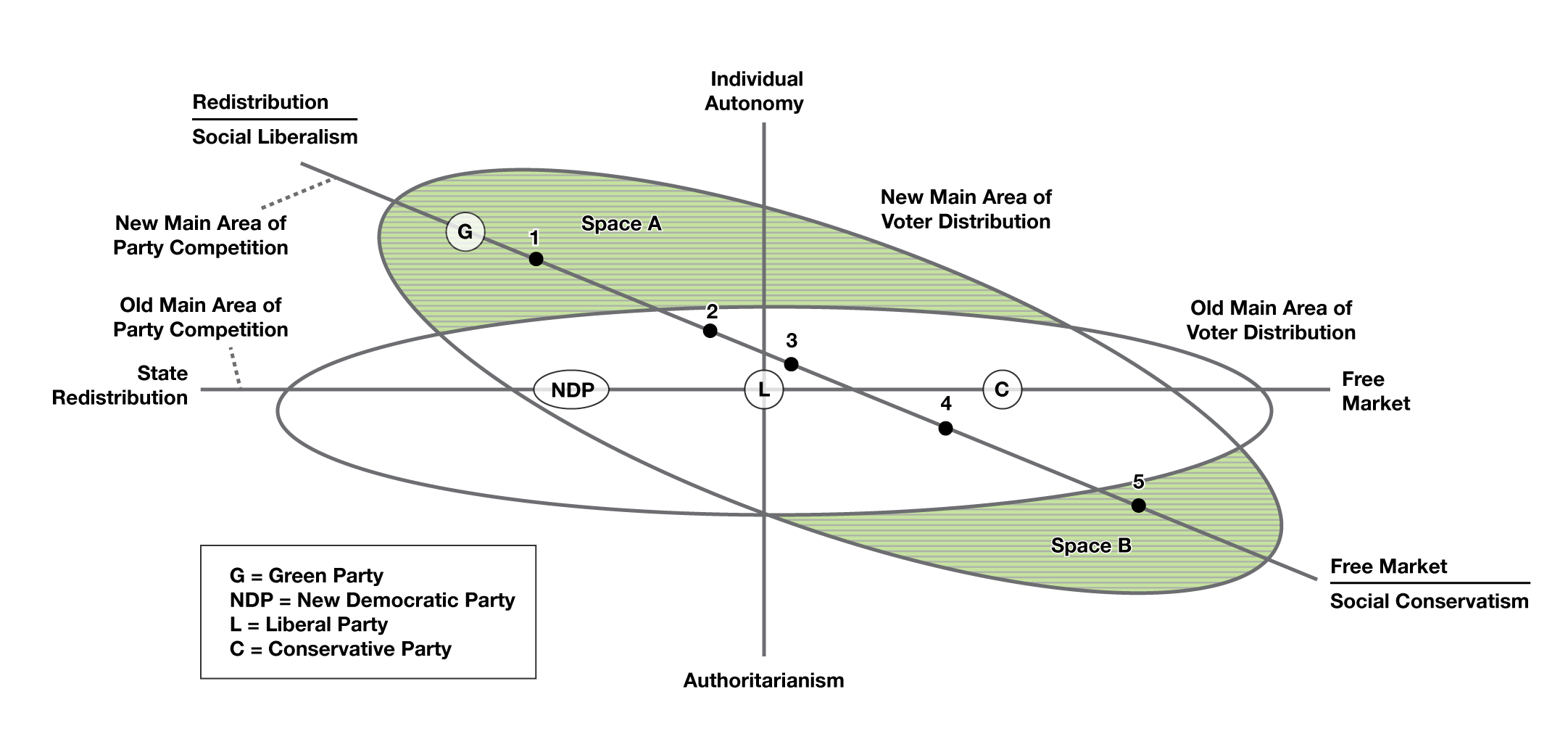

In practice democratic will formation in representative democracies takes place largely through political party competition in an electoral cycle. Two factors explain the dynamics of democratic party systems (Kitschelt 1995). Firstly, political demand refers to the underlying societal factors and social changes that create constituencies of people with common interests. People form common political preferences and interests on the basis of their common positions in the social structure. For example, changes in the types of jobs generated by the economy will affect the size of electoral support for labour unions and labour union politics. Secondly, political supply refers to the strategies and organizational capacities of political parties to deliver an appealing political program to particular constituencies. For example, the Liberal Party of Canada often attempts to develop policies and political messaging that will position it in the middle of the political spectrum where the largest group of voters potentially resides. In the 2011 election, due to leadership issues, organizational difficulties, and the strategies of the other political parties, they were not able to deliver a credible appeal to their traditional centrist constituency and suffered a large loss of seats in Parliament (see Figure 17.13). In the 2015 election, the Conservative Party’s program and messaging consolidated its “right wing” constituency of social conservatives and free market proponents but failed to appeal to people in the center of the Canadian political spectrum (see Figure 17.14).

The relationship between political demand and political supply factors in democratic will formation can be illustrated by mapping out constituencies of voters on a left/right spectrum of political preferences (Kitschelt 1995; see Figure 17.14). While the terms “left wing” and “right wing” are notoriously ambiguous (Ogmundson 1972), they are often used in a simple manner to describe the basic political divisions of modern society.

In Figure 17.15, one central axis of division in voter preference has to do with the question of how scarce resources are to be distributed in society. At the right end of the spectrum are economic conservatives who advocate minimal taxes and a purely spontaneous, competitive market-driven mechanism for the distribution of wealth and essential services (including health care and education), while at the left end of the spectrum are socialists who advocate progressive taxes and state redistribution of wealth and services to create social equality or “equality of condition.” A second axis of division in voter preference has to do with social policy and “collective decision modes.” At the right end of the spectrum is authoritarianism (law and order, limits on personal autonomy, exclusive citizenship, hierarchical decision making, etc.), while at the left end of the spectrum is individual autonomy or expanded democratization of political processes (maximum individual autonomy in politics and the cultural sphere, equal rights, inclusive citizenship, extra-parliamentary democratic participation, etc.). Along both axes or spectrums of political opinion, one might imagine an elliptically shaped distribution of individuals, with the greatest portion in the middle of each spectrum and far fewer people at the extreme ends. The dynamics of political supply in political party competition follow from the way political parties try to position themselves along the spectrum to maximize the number of voters they appeal to while remaining distinct from their political competitors.

Sociologists are typically more interested in the underlying social factors contributing to changes in political demand than in the day-by-day strategies of political supply. One influential theory proposes that since the 1960s, contemporary political preferences have shifted away from older, materialist concerns with economic growth and physical security (i.e., survival values) to postmaterialist concerns with quality of life issues: personal autonomy, self-expression, environmental integrity, women’s rights, gay rights, the meaningfulness of work, habitability of cities, etc. (Inglehart 2008). From the 1970s on, postmaterialist social movements seeking to expand the domain of personal autonomy and free expression have encountered equally postmaterialist responses by neoconservative groups advocating the return to traditional family values, religious fundamentalism, submission to work discipline, and tough-on-crime initiatives. This has led to a new postmaterialist cleavage structure in political preferences.

In Figure 17.14 we have represented this shift in political preferences in the difference between the ellipse centred on the free-market/state redistribution axis and the ellipse centred on the free-market-social-conservativism/ redistribution-social-liberalism axis (Kitschelt 1995). As a result of the development of postmaterialist politics, the “left” side of the political spectrum has been increasingly defined by a cluster of political preferences defined by redistributive policies, social and multicultural inclusion, environmental sustainability, and demands for personal autonomy, etc., while the “right” side has been defined by a cluster of preferences including free-market policies, tax cuts, limits on political engagement, crime policy, and social conservative values, etc.

What explains the emergence of a postmaterialist axis of political preferences? Arguably, the experience of citizens for most of the 20th century was defined by economic scarcity and depression, the two world wars, and the Cold War resulting in the materialist orientation toward the economy, personal security, and military defence in political demand. The location of individuals within the industrial class structure is conventionally seen as the major determinant of whether they preferred working-class-oriented policies of economic redistribution or capitalist-class-oriented policies of free-market allocation of resources. In the advanced capitalist or post-industrial societies of the late 20th century, the underlying class conditions of voter preference are not so clear however. Certainly the working-class does not vote en masse for the traditional working class party in Canada, the NDP, and voters from the big business, small business, and administrative classes are often divided between the Liberals and Conservatives (Ogmundson 1972).

Kitschelt (1995) notes two distinctly influential dynamics in western European social conditions that can be applied to the Canadian situation. Firstly, in the era of globalization and free trade agreements people (both workers and managers) who work in and identify with sectors of the economy that are exposed to international competition (non-quota agriculture, manufacturing, natural resources, finances) are likely to favour free market policies that are seen to enhance the global competitiveness of these sectors, while those who work in sectors of the economy sheltered from international competition (public-service sector, education, and some industrial, agricultural and commercial sectors) are likely to favour redistributive policies. Secondly, in the transition from an industrial economy to a postindustrial service and knowledge economy, people whose work or educational level promotes high levels of communicative interaction skills (education, social work, health care, cultural production, etc.) are likely to value personal autonomy, free expression, and increased democratization, whereas those with more instrumental task-oriented occupations (manipulating objects, documents, and spreadsheets) and lower or more skills-oriented levels of education are likely to find authoritarian and traditional social settings more natural. In Figure 17.14, new areas of political preference are shown opening up in the shaded areas labelled Space A and Space B.

The implication Kitschelt draws from this analysis is that as the conditions of political demand shift, the strategies of the political parties (i.e., the political supply) need to shift as well (see Figure 17.14). Social democratic parties like the NDP need to be mindful of the general shift to the right under conditions of globalization, but to the degree that they move to the centre (2) or the right (3), like British labour under Tony Blair, they risk alienating much of their traditional core support in the union movement, new social movement activists, and young people. The Green Party is also positioned (1) to pick up NDP support if the NDP move right. On the other side of the spectrum, the Conservatives do not want to move so far to the right (5) that they lose centrist voters to the Liberals or NDP (as was the case in the Ontario provincial election in 2014 and the federal election in 2015). However, to the degree they move to the centre they risk being indistinguishable from the Liberals and a space opens up to the right of them on the political spectrum. The demise of the former Progressive Conservative party after the 1993 election was precipitated by the emergence of postmaterialist conservative parties further to the right (Reform and the Canadian Alliance).

This model of democratic will formation in Canada is not without its problems. For one thing, Kitschelt’s model of the spectrum of political party competition is based on European politics. It does not take into account the important role of regional allegiances that cut across the left/right division and make Canada an atypical case (in particular the regional politics of Quebec and western Canada). Similarly, the argument that political preferences have shifted from materialist concerns with economic growth and distribution to postmaterialist concerns with quality-of-life issues is belied by opinion polls which consistently indicate that Canadians rate the economy and unemployment as their greatest concerns, (although climate change and health care often rank highly in opinion polls). On the other hand, it is probably the case that postmaterialist concerns are not addressed effectively in current formal political processes and political party platforms. Canadians have been turning increasingly to nontraditional political activities like protests and demonstrations, signing petitions, and boycotting or “boycotting” to express their political grievances and aspirations. With regard to the distinction between direct democracy and representative democracy, it is interesting to note that in the current era of declining voter participation in elections, especially among young people, people (especially young people) are turning to more direct means of political engagement (See Figure 17.15).

N/A means not applicable. * means statistically different from 22 to 29-year-olds (p<0.05).

| Types of political participation | Percentage of Political Participation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 15 to 21 | 22 to 29 | 30 to 44 | 45 to 64 | 65 or older | |

| Follow news and current affairs daily | 68* | 35* | 51 | 66* | 81* | 89* |

| Voted in at least one election | 77* | N/A | 59 | 71* | 85* | 89* |

| Voted in the last federal election | 74* | N/A | 52 | 68* | 83* | 89* |

| Voted in the last provincial election | 73* | N/A | 50 | 66* | 82* | 88* |

| Voted in the last municipal or local election | 60* | N/A | 35 | 52* | 70* | 79* |

| At least one non-voting political behaviour | 54* | 59 | 58 | 57 | 56 | 39* |

| Searched for information on a political issue | 26* | 36 | 32 | 26* | 25* | 17* |

| Signed a petition | 28* | 27* | 31 | 31 | 29 | 16* |

| Boycotted a product or chose a product for ethical reasons | 20* | 16* | 25 | 25 | 21* | 8* |

| Attended a public meeting | 22* | 17 | 16 | 23* | 25* | 20* |

| Expressed his/her views on an issue by contacting a newspaper or a politician | 13* | 8 | 9 | 13* | 16* | 12* |

| Participated in a demonstration or march | 6* | 12* | 8 | 6 | 6* | 2* |

| Spoke out at a public meeting | 8* | 4 | 5 | 9* | 10* | 7* |

| Volunteered for a political party | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4* | 4 |

Note: Voting rates will differ from those of Elections Canada, which calculates voter participation rates based on number of eligible voters.

Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2003.

What might that more direct form of participation look like? In the following videos you are introduced to one form of citizen participation in the formation of policy. Can you think of other examples of how citizens can influence the formation of policy in contemporary democratic states?

5.3 The De-Centring of the State: Terrorism, War, Empire, and Political Exceptionalism

In Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014), the post-apocalyptic narrative of brewing conflict between the apes — descendants of animal experimentation and genetic manipulation — and the remaining humans — survivors of a human-made ape virus pandemic — follows a familiar political story line of mistrust, enmity, and provocation between opposed camps. The film may be seen as a science fiction allegory of any number of contemporary cycles of violence, including the 2014 Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which was concurrent with the film’s release. In the first part of the movie, we see the two communities in a kind of pre-political state, struggling in isolation from one another in an effort to survive. There is no real internal conflict or disagreement within them that would have to be settled politically. The communities have leaders, but leaders who are listened to only because of the respect accorded to them. However, when the two communities come into contact unexpectedly, a political dynamic begins to emerge in which the question becomes whether the two groups will be able to live in peace together or whether their history and memory of hatred and disrespect will lead them to conflict. It is a story in which we ask whether it is going to be the regulative moral codes that govern everyday social behaviour or the friend/enemy dynamics of politics and war that will win the day. The underlying theme is that when the normal rules that govern everyday behaviour are deemed no longer sufficient to conduct life, politics as an exception in its various forms emerges.

The concept of politics as exception has its roots in the origins of sovereignty (Agamben, 1998). It was articulated most clearly in the 1920s in the work of Carl Schmitt (1922) who later became juridical theorist aligned with the German Nazi regime in the 1930s. Schmitt argued that the authentic activity of politics–the sphere of “the political”–only becomes clear in moments of crisis when leaders are obliged to make a truly political decision, (for example, to go to war). This occurs when the normal rules that govern decision making or the application of law appear no longer adequate or applicable to the situation confronting society. Specifically, we refer to a state of exception when the law or the constitution is temporarily suspended during a time of crisis so that the executive leader can claim emergency powers. Schmitt eventually applied this principle to justify the German National Socialist Party’s suspension of the Weimar constitution in 1933, as well as the Führerprinzip (principle of absolute leadership) that characterized the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler. Nevertheless political exceptionalism is a reoccurring theme in politics and as situations of crisis have become increasingly normal in recent decades — the war on terror, failed states, the erosion of sovereign power, etc. — it becomes necessary for sociologists to examine the role of politics under conditions of social crisis.

A subplot in Dawn of the Planet of the Apes involves the relationship between the leader of the apes, Caesar, and Koba, whose life as a victim of medical experimentation leads him to hate humans and challenge Caesar’s attempts to find reconciliation with them. Until the moment of contact, the apes are able govern themselves by a moral code and mutual agreement on decisions. It is an ideal, peaceful pre-political society. One central tenet of the apes’ moral identity was that “ape does not kill ape,” unlike the humans whose society disintegrated into violent conflict following the global pandemic. However, when Koba’s betrayal of Caesar leads to a war with the humans that threatens the apes’ survival, Caesar is forced to make an impossible decision: break the moral code and kill Koba, or risk further betrayal and dissension that will undermine his ability to lead. Caesar’s solution is to kill Koba but only after making a crucial declaration that keeps the apes’ moral code intact: “Koba not ape!” He essentially declares that Koba’s transgression of the apes’ way of life was so egregious that he could no longer be considered an ape and therefore he can be killed.

This is an example of political exceptionalism. In this case, Caesar suspends the law of the apes and dispenses with Koba in his first act of emergency power. Caesar decides who is and who is not an ape; who is and who is not protected by ape law. The law is preserved, but it is revealed to be radically fluid and dependent on Caesar’s decision.

This possibility of the state of exception is built in to the structure of the modern state. The modern state system, based on the concept of state sovereignty, came into existence after the Thirty Years War in Europe (1618–1648) as a solution to the problem of continual, generalized states of war. The principle of state sovereignty is that within states, peace is maintained by a single rule of law, while war (i.e., the absence of law) is expelled to the margins of society as a last resort in times of exception. The concept of “society” itself, as a peaceable space of normative interaction, depends on this expulsion of violent conflict to the borders of society (Walker, 1993). When society is threatened however, from without or within, the conditions of a temporary state of exception emerge. Constitutional governments often provide a formal mechanism for declaring a state of exception or emergency powers, like the former Canadian War Measures Act. Many observers of contemporary global conflict have noted, however, that what were once temporary states of exception — wars between states, wars within states, wars by non-state actors, and wars or crises resulting in the suspension of laws — have become increasingly permanent and normalized in recent years. The exception is increasingly becoming the norm (Agamben 2005; Hardt and Negri, 2004).

Several phenomena of current political life allow us to examine political exceptionalism: global terrorism, the contemporary nature of war, the re-emergence of Empire, and the routine use of states of exception.

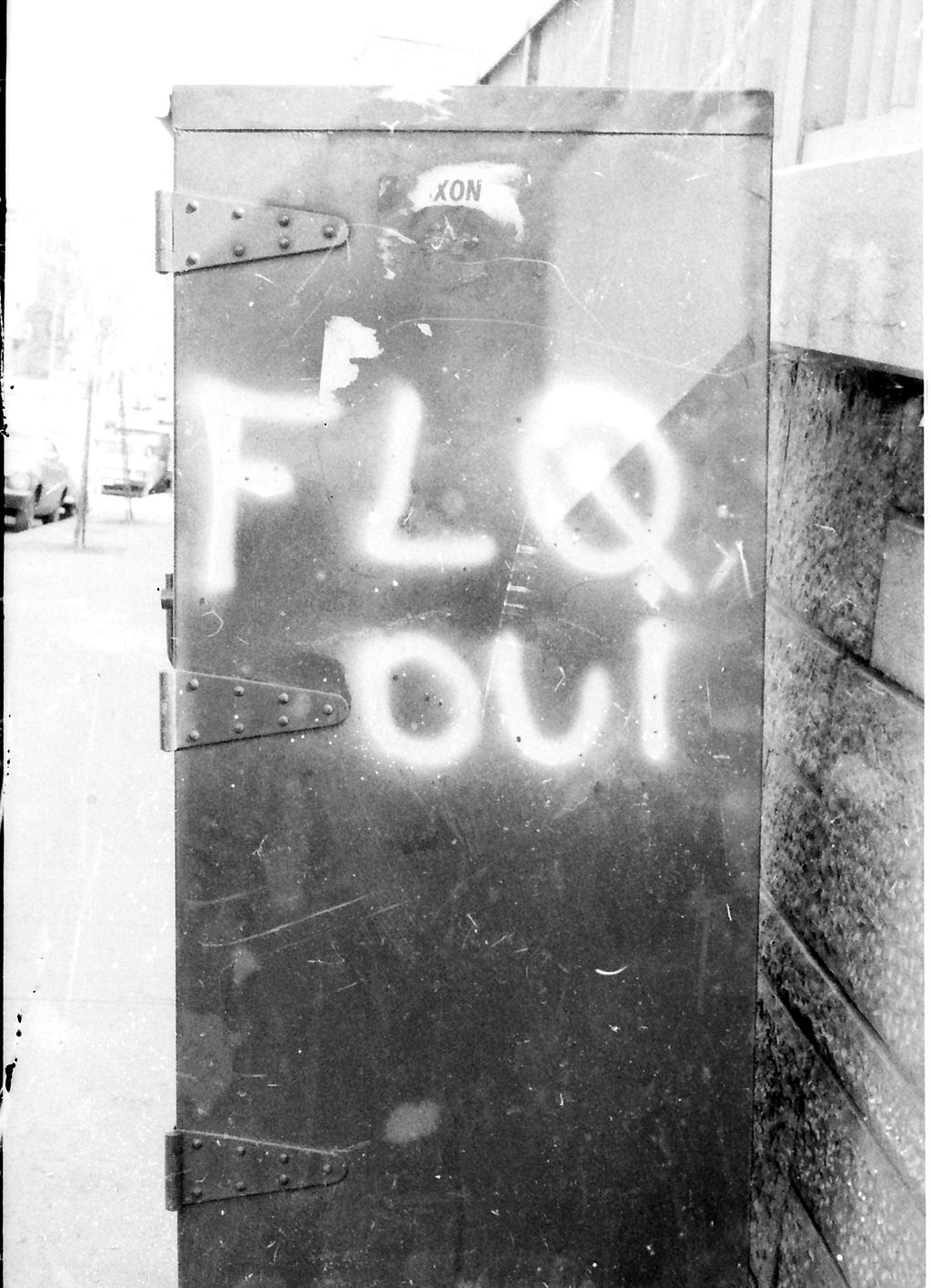

5.3.1 Terrorism: War by non-state actors

Since 9/11, the role of terrorism in restructuring national and international politics has become apparent. As we defined it earlier, terrorism is the use of violence on civilian populations and institutions to achieve political ends. Typically we see this violence as a product of non-state actors seeking radical political change by resorting to means outside the normal political process. They challenge the state’s legitimate monopoly over the use of force in a territory. Al-Qaeda for example is an international organization that had its origin in American-funded efforts to organize an insurgency campaign against the Russian occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s. Its attacks on civilian and military targets, including the American embassies in East Africa in 1998, the World Trade Center in 2001, and the bombings in Bali in 2002, are means to demand the end of Western influence in the Middle East and the establishment of fundamentalist Wahhabi Islamic caliphates. On a much smaller scale the FLQ (Front de libération du Québec) resorted to bombing mailboxes, the Montreal Stock Exchange, and kidnapping political figures to press for the independence of Quebec.

Terrorism is an ambiguous term, however, because the definition of who or what constitutes a terrorist differs depending on who does the defining. There are three distinct phenomena that are defined as terrorism in contemporary usage: the use of political violence as a means of revolt by non-state actors against a legitimate government, the use of political violence by governments themselves in contravention of national or international codes of human rights, and the use of violence in war that contravenes established rules of engagement, including violence against civilian or non-military targets (Hardt and Negri 2004). Noam Chomsky argues, for example, that the United States government is the most significant terrorist organization in the world because of its support for illegal and irregular wars, its backing of authoritarian regimes that use illegitimate violence against their populations, and its history of destabilizing foreign governments and assassinating foreign political leaders (Chomsky 2001; Chomsky and Herman 1979).

[JR: Please insert Youtube video, Free Will, (2020), “Noam Chomsky on Terrorism” at url, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ae4UQ4V1iKc&pp=QAA%3D]

5.3.2 War: Politics by other means

Even before there were modern nation-states, political conflicts arose among competing societies or factions of people. Vikings attacked continental European tribes in search of loot, and later, European explorers landed on foreign shores to claim the resources of indigenous peoples. Conflicts also arose among competing groups within individual sovereignties, as evidenced by the bloody English and American civil wars and the Riel Rebellion in Canada. Nearly all conflicts in the past and present, however, are spurred by basic desires: the drive to protect or gain territory and wealth, and the need to preserve liberty and autonomy. They are driven by an inside/outside dynamic that provides the underlying political content of war. War is defined as a form of organized group violence between politically distinct groups. As the 19th century military strategist Carl von Clausewitz (1832) said, war is merely the continuation of politics by other means.

In the 20th century, 9 million people were killed in World War I and another 61 million people were killed in World War II. The death tolls in these wars were of such magnitude that the wars were considered at the time to be unprecedented. World War I, or “the Great War,” was described as the war that would end all wars, yet the manner in which it was settled led directly to the conditions responsible for the declaration of World War II. In fact, the wars were not unprecedented. Since the establishment of the modern centralized state in Europe, there have been six European wars involving alliances between multiple nation-states at approximately half-century intervals. Prior to World War I and World War II, there was the Thirty Years War (1618–1648), the War of Spanish Succession (1702–1713), the Seven Years War (1756–1763), and the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815) (Dyer, 2014). The difference in the two 20th century world wars is that advances in military technology and the strategy of total war (involving the targeting of civilian as well as military targets) led to a massive increase in casualties. The total dead in 20th century wars is estimated at 111 million, approximately two-thirds of the 175 million people killed in total in war in the thousand years between 1000 and 2000 CE (Tepperman, 2010).

War is typically understood as armed conflict that has been openly declared between or within states. However recent warfare, like Canada’s involvement in the NATO mission in Afghanistan (from 2001 to 2014), more typically takes the form of asymmetrical conflict between professional state armies and insurgent groups who rely on guerilla tactics (Hardt and Negri, 2004). Asymmetrical warfare is defined by the lack of symmetry between the sides of a violent military conflict. There is a significant imbalance of technical and military means between combatants, which has been referred to by American military strategists as full spectrum dominance. This shifts the nature of the conflict to insurgency and counter-insurgency tactics in which the dominant, professional armies aim their efforts of deterrence against both the military operations of their opponents and the potentially militarized population. Counter-insurgency strategies seek not only to defeat the enemy army militarily but to control it with social, political, ideological, and psychological weapons. The Canadian army’s “model village” clear, hold, and build strategy in Afghanistan is an example of this, combining conventional military action with humanitarian aid and social and infrastructure investment (Galloway, 2009). On the other side, the insurgent armies compensate for their military weakness with the unpredictable tactics of guerilla war in which maximum damage can be done with a minimum of weaponry (Hardt and Negri, 2004).

One of the outcomes of contemporary warfare has been the creation of a condition of global post-security in which, as Hardt and Negri put it, “lethal violence is present as a constant potentiality, ready always and everywhere to erupt” (2004, p. 4). Partly as a reaction to this phenomenon and partly as a cause, we can speak of the development of war systems, or the normalization of militarization. This is “the contradictory and tense social process in which civil society organizes itself for the production of violence” (Geyer, 1989). This process involves an intensification of the conceptual division between the outsides and insides of nation-states, the demonization of enemies who threaten “us” from the outside (or the inside), the normalization of military ways of thinking and military perspectives on policy, and the propagation of ideologies that romanticize, sanitize, and validate military violence as a solution to problems or as a way of life (Graham, 2011). As many commentators have noted, Canada’s relationship to military action has shifted during the Afghan operation from its Lester Pearson era of peacekeeping to a more militant stance in line with the normalization of militarization (Dyer, 2014).

5.3.3 Empire

The breakdown of states due to warfare or internal civil conflict is one way in which the sovereign nation-state is undermined in times of exception. Another way in which the sovereignty of the state has been undermined is through the creation of supra-state forces like global capitalism and international trade agreements that reduce or constrain the decision-making abilities of national governments. When these supranational forces become organized on a formal basis, we might begin to speak about the re-emergence of empires as a type of political exception. Empires have existed throughout human history, but arguably there is something very unique about the formation of the contemporary global Empire. In general an empire (1) refers to a geographically widespread organization of individual states, nations, and people that is ruled by a centralized government, like the Roman Empire or the Austro-Hungarian Empire. However, some argue that the formation of a contemporary global order has seen the development of a new unbounded and centre-less type of empire. Empire (2) today refers to a supra‐national, global form of sovereignty whose territory is the entire globe and whose organization forms around the nodes of a network form of power. These nodes include the dominant nation‐states, supranational institutions (the UN, IMF, GATT, WHO, G7, etc.), major capitalist corporations, and international Non-Governmental Organizations or NGOs (Medecins San Frontieres, Amnesty International, CUSO, Oxfam, etc.) (Hardt and Negri, 2000).

As a result of the formation of this type of global empire, war, for example, is increasingly not fought between independent sovereign nation-states but increasingly as a kind of global-scale police action in which several states — or “coalitions of the willing” — intervene on humanitarian or security grounds to suppress dissent or conflict in different parts of the globe. Key to this shift in the nature of the use of force is the way in which military action, traditionally understood as armed combat between sovereign states, is reconceptualized as police action, traditionally understood as the legitimate use of force within a sovereign state. As the borders between states erode, the entire globe is reconceived as a single, vast, internal sovereign state to be managed and governed as a domestic problem.

5.3.4 Normalization of Exception

As we noted above, a state of exception refers to a situation when the law or the constitution is temporarily suspended during a time of crisis so that the executive leader can claim emergency powers. During warfare for example, it is typical for governments to temporarily suspend the normal rule of law and institute martial law. However, when times of crisis become the norm, this modality of power is resorted to more frequently and more permanently both on a large scale and small scale.Perhaps the most famous example of normalized political exceptionalism was the suspension of the Weimar Constitution by the Nazis in Germany between 1933 and 1945. On the basis of Hitler’s Decree for the Protection of the People and the State, the personal liberties of Germans were “legally” suspended, making the concentration camps for political opponents, the confiscation of property, and the Holocaust in some sense lawful actions. Under Alfredo Stroessner’s regime in Paraguay in the 1960s and 1970s, this form of legal illegality was taken to the extreme. Citing the state of emergency created by the global Cold War struggle between communism and democracy, Stroessner suspended Paraguay’s constitutional protection of rights and freedoms permanently except for one day every four years when elections were held (Zizek 2002). On a smaller scale, albeit with global implications, U.S. President George Bush’s 2001 military order that authorized the trial by military tribunal and indefinite detention of “unlawful combatants” and individuals suspected of being involved in terrorist activities enabled a similar suspension of constitutional and international laws. The U.S. detention centre at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where individuals were tortured and held without trial or due process, is a legally authorized space that is nevertheless outside of the jurisdiction and protection of the law (Agamben 2005).

Canada’s most famous incident of peacetime state of exception was Pierre Trudeau’s use of the War Measures Act in 1970 during the October Crisis. The War Measures Act was used to suspend civil liberties and mobilize the military in response to a state of “apprehended insurrection” following the FLQ’s kidnapping of Quebec politician Pierre Laporte and British diplomat James Cross. During the period of the War Measures Act, 3,000 homes were searched and 497 individuals were arrested without due process, including several people in Vancouver who were found distributing the FLQ’s manifesto. Only 62 people were ever charged with offences, and the FLQ cells responsible for the kidnappings did not number more than a handful of individuals (Clément 2008). Although this incident is the most famous example of political exceptionalism in Canada, there are a number of pieces of legislation and processes that involve the mechanism of localized suspension of the law, notably the use of Ministerial Security Certificates under the 2001 Anti-Terrorism Act, which enables the indefinite detention of suspected terrorists; the Public Works Protection Act, which was used to detain protesters at the Toronto G20 Summit in 2010; and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (2002), which enables the routine confinement and detention of stateless refugees and “boat people” arriving in Canada.

[JR: Please insert Youtube video, (2017), “Noam Chomsky: Neoliberalism is Destroying out Democracy” at url, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/noam-chomsky-neoliberalism-destroying-democracy/]

5.4 Theoretical Perspectives on Government and Power

There has been considerable disagreement among sociologists about the nature of power, politics, and the role of the state in society. This is not surprising as any discussion of power and politics is bound to be political itself, that is to say divisive or “politicized.” It is arguably the case that we are better positioned today, after a period of prolonged political exceptionalism, to see the nature of power and the state more clearly than during periods of peace or détente. It is during moments when the regular frameworks of political practice and behaviour are disrupted — through revolution, suspension of the law, the failure of states, war, or counter-insurgency — that the underlying basis of the relationship between the social and the political, or society and the state can be revealed and rethought.

Earlier in this chapter, we noted that the radical standpoint of anarchism provides a useful standpoint from which to examine the sociological question of the state. A key sociological question posed by anarchism is: Why is government in the form of the state needed in the first place? Could we not do just as well without state government? What is the state for? On these questions, the organizational frameworks or paradigms that characterize the sociological tradition — here we have been examining structural functionalism, critical sociology, and symbolic interactionism — have provided different approaches and answers.

5.4.1 Functionalism

Talcott Parsons, in a classic statement of structural functionalism, wrote: “I conceive of political organization as functionally organized about the attainment of collective goals, i.e., the attainment or maintenance of states of interaction between the system and its environing situation that are relatively desirable from the point of view of the system” (Parsons, 1961, p. 435). From the viewpoint of the system, the “polity” exists to perform specific functions and meet certain needs generated by society. In particular, it exists to provide a means of attaining “desirable” collective goals by being the site of collective decision making. According to functionalism, modern forms of government have four main purposes: planning and directing society, meeting collective social needs, maintaining law and order, and managing international relations.

The abstractness of Parsons’s language is both a strength and weakness of the functionalist approach to government and the state. It is a strength in the sense that it enables functionalist sociologists to abstract from particular societies to examine how the function of collective decision making and goal attainment is accomplished in different manners in different types of society. It does not presuppose that there is a “proper” institutional (or other) structure that defines government per se, nor does it presuppose what a society’s collective goals are. The idea is that the social need for collective goal attainment is the same for all societies, but it can be met in a variety of different ways. In this respect it is interesting to note that many nomadic or hunter-gather societies developed mechanisms that specifically prevent formal, enduring state organizations from developing. The typical “headman” structure in hunter-gatherer societies is a mechanism of collective decision making in which the headman takes a leadership role, but only on the provisional basis of his recognized prestige, his ability to influence or persuade, and his attunement with the group’s desires. The polity function is organized in a manner that actively fends off the formation of a permanent state institution (Clastres, 1989). Similarly Parsons’s own analysis of the development and differentiation of the institutions of the modern state (legislative, executive, judiciary) shows how political organization in Western societies emerged from a period of “religio-political-legal unity” in which the functions performed by church and state were not separate.

The weakness in Parsons’s abstraction is that it allows functionalists to speak about functions and needs from the “point of view of the system” as if the system had an independent or neutral existence. A number of very important aspects of power disappear from view by a kind of sleight of hand when sociologists attempt to take this viewpoint. One dominant functionalist framework for understanding why the state exists is pluralist theory. In pluralist theory, society is made up of numerous competing interest groups — capital, labour, religious fundamentalists, feminists, LGBTQ, small business, homeless people, taxpayers, elderly, military, pacifists, etc. — whose goals are diverse and often incompatible. In democratic societies, power and resources are widely distributed, albeit unevenly, so no one group can attain the power to permanently dominate the entire society. Therefore, the state or government has to act as a neutral mediator to negotiate, reconcile, balance, find compromise, or decide among the divergent interests. From the point of view of the system, it maintains equilibrium between competing interests so that the functions of social integration and collective goal attainment can be accomplished. In this model, the state is an autonomous institution that acts on behalf of society as a whole. It is independent of any particular interest group.On one hand, the pluralist model seems to conform to commonsense understandings of democracy. Sometimes one group wins, sometimes another. Usually there are compromises. Everyone has the potential to have input into the political decision-making process. However, critics of pluralist theory note that what disappears from an analysis that attempts to take the neutral point of view of the system and its functions is, firstly, the fact that the system itself is not disinterested — it is structured to maintain inequality; secondly, that some competing interests are not reconcilable or balanceable — they are fundamentally antagonistic; and, thirdly, that politics is not the same as administration or government — it is in essence disruptive of systems and equilibrium. The difficulty Parsons has in accounting for these aspects of political life comes out in his discussion of the use of force to maintain the state’s legally sanction normative order (i.e., the “the highest order of norms regulating the behaviour of units within the society”). Parsons (1961) writes,

No society can afford to permit any other normative order to take precedence over that sanctioned by “politically organized society.” Indeed, the promulgation of any such alternative order is a revolutionary act, and the agencies responsible for it must assume the responsibility of political organization (p. 435).

He suggests that an alternative normative order is not simply the product of a competing social interest that might be balanced with others, but a revolutionary threat to the entire system. From the “point of view of the system,” an alternative normative order is inadmissible and must be either violently suppressed or permitted to take responsibility for founding a new political organization of society.

5.4.2 Critical Sociology

The question of why the state exists has been answered in a variety of different ways by critical sociologists. In the Marxist tradition, the power of the state is principally understood as a means by which the economic power of capital is exercised and maintained. The state itself is in many respects subservient to the interests of capital. As Marx and Engels put it in The Communist Manifesto, “The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie” (1848, p. 223). While the state appears to be the place where power is “held,” the power of the state is in a sense secondary to the power of capital.