Pathos: Audience Adaptation

Omar Nawara; Shalyn Fladager; and Alex (Robert) Phillips

Introduction

Adapting a speech to the audience can increase a speech’s effectiveness. In the preparation stages, creating a speech for a specific audience can help to guide the stylistic and content choices of the speech. There are many aspects to consider when adapting to an audience, and it is important to know that it requires presenting what one has to say in a way that resonates with the audience, and not just telling them what they want to hear.

This chapter will address the many aspects and considerations involved with audience adaptation.

Factors in Audience Analysis

There are many factors that must be considered before giving a speech. In adapting to the audience, it is important to consider all aspects of the audience and setting for the speech.

(i) Audience Expectations

The audience will have expectation about the occasion, topic and speaker. There are situations where it is either inappropriate or appropriate to go against audience expectation; however it is generally advisable to deliver a speech that meets the audience’s expectations

(ii) Knowledge of the topic

It is important to know what the audience already knows about a topic. By presenting information that the audience is unfamiliar with, the audience may lose interest and not be able to follow along with the speech. On the other hand, by telling the basic information to an audience with an advanced understanding, you risk delivering a speech that sounds condescending. To avoid this, always give a short review of what the audience should know before you get into the main points of a speech, that way everyone will be on the same page

(iii) Attitude towards topic

A speaker must know the audience’s attitude towards the topic they are presenting about. If the audience is concerned or hesitant about an aspect of the speech that the speaker does not address, the speech may lose its power.

(iv) Audience Size

For large audiences, speakers will need to be louder, elevated (or in a place where the audience members can see) and will need to understand that there is a wider range of people in the audience with different attitudes, expectations and knowledge on the speech topic. Smaller audiences can be less formal and use common language. A lower volume is also necessary.

(v) Demographics

This refers to factors such as age, gender, religion, ethnic background, class, sexual orientation, occupation, education and group membership. Understanding the demographics of the audience will help in the understanding of other aspects of the audience.

(vi) Setting

Consider room size, arrangement, time of day, temperature, internal and external noises. Also know what resources are available – speakers, projector, stage. Depending on the time of the day, the speaker can adapt to a lively, hungry or tired audience.

(vii) Voluntariness

A more receptive audience will be one that is voluntarily. An involuntary audience will be less interested in the speech. It is important to adapt the speech to gain interest or hold interest of the audience.

(viii) Egocentrism

Most audiences will care about things that directly affect them or a topic that they can closely relate to. A speaker must craft the speech to show the audience why they topic they are discussing is of important to an audience.

Audience Attitude

Discover the Stance of the Listener

The first thing to consider when adapting a speech to an audience is to do some background research. Using opinion polls can help to understand certain attitudes about the audience. Opinion polls many not give an exact answer to the audiences opinion, but they can help to determine the audiences stance on an issue. Unfortunately, it is nearly impossible to account for the attitude of everyone in the audience, as there are often varying degrees of opinion. For this reason it is good to ask “is the majority of my audience”:

- In favour of this issue

- Indifferent about the issue

- Opposed to the issue

Audience in Favour

If the audience is found to be already in favour of the opinion, it is not necessary to spend time and effort convincing them that the train of thought is valid; the speech can be focused on a specific course of action.

- Say for example one is talking to a group about how trans-fats are bad for a persons health. It is common knowledge that trans-fats are harmful to the body. Aiming the speech at persuading people that trans-fats are bad would be a waste of effort as people already agree with that fact. The focus of the speech could be put on some action the audience can take to limiting there trans-fat intake such as reading labels or cooking at home.

Since the audience is already in agreement with the opinion of the speaker, it can be used as a rallying point to an action.

Audience has no opinion

There are two levels of no opinion; neutral and apathetic

- Neutral: In this case the audience has not taken a stance on the issue. In this situation, a speaker can assume that the audience has the ability to reason and accept sound arguments. Working a speech to present the best possible arguments with concrete supporting information can help move the audience to form an opinion.

- consider trying to persuade someone to use a particular type of sandwich bag. For the majority of people, a sand bag is a sandwich bag regardless of the name. Using arguments such as cost, features, whether the bag was produced ethically would help to persuade the audience as logical arguments will persuade easily since there is no emotional aspect to overcome.

- Apathetic: In this scenario the audience has no interest in the issue at all. The speech should focus less on logical material but more on points that are directed at what the audience personally needs to know and why they should care about the topic

- consider trying to persuade a group of people to start saving for their retirement. These people are not against saving, but they have no interest in putting money away, they have an income and they enjoy living day to day. To persuade these people to save it might be beneficial to show them points that affect their emotions. Things such as consequences of loosing that source of income and having nothing put away, the benefits of being retired with savings and so on. Providing points that show what is in it for the audience would be most effective. Find a way to demonstrate the need for savings.

Opposed

This stance also has two levels; slightly negative or openly hostile.

- Slightly Negative: A speech should aim to reduce the audience’s negative views. Here, it is important to be objective and clear enough so that people will consider the proposal or at least understand the position of the speech position.

- The city is proposing a tax increase for the City of Saskatoon at a meeting at City Council. Most people do not like the idea of having to pay more money than they already do. Arguments will have to be kept clear and to the point and it could be beneficial to discuss the following questions: what are the cost increases of running the city that result in this tax increase and why have they occurred? Where will this increased revenue for the city be going and why? It would be beneficial to discuss how everyone benefits.

- Openly Hostile: In this situation, it is a good idea to approach the issue less directly and to be less ambitious with the speeches goals for the audience. Actions that require less of a change in attitude might be able to get the audience to start looking at the issue in a different way.

- Consider speaking to a group of anti-nuclear enthusiasts on developing nuclear power in the area. It would be a bad idea to proclaim the greatness of nuclear power and demand that it should be implemented immediately. Presenting arguments that address concerns of your audience would be the best approach. Depending on the research completed, one could either discuss how some concerns are not valid or how valid concerns can be remedied. Whatever is addressed it must be supported with factual information and a deep respect for the audience’s fears and misgivings. Remember that before and audience can be persuaded, they feel that your idea is valid, beneficial and safe.

The Captive Audience

Voluntary vs. Captive Audience

When speaking, there are two major audience types to deal with; voluntary and captive. A voluntary audience is a group of people who have come to hear a speaker on their own free will. This audience is generally a little easier to speak to because it is often made up of people who are like-minded to that of the speaker (i.e. people who share common beliefs and ideas). Also whenever a person has a choice to listen to someone, they are generally more willing to listen to their arguments.

A captive audience is much more difficult to deal with. As the name suggests this audience type is made up of people who are at a presentation because they have to be there. Typical captive audiences are those who are required to attend a speech or seminar for work, class or other commitment that requires their attendance. The challenge with this audience is to figure out how to adapt a speech to grab and hold the attention of people who would never have thought of listening to the speech had they not been forced to. This section looks at tailoring a speech to acquire and keep the audiences attention.

General Rules

What is the audience interested in?

People want to talk about and listen to what they are interested in. If you understand the demographic of the audience, it may be beneficial to brainstorm what the audience might want to hear.

Why should they listen?

Captive audiences don’t initially have a reason to listen to and so the speaker must provide them with a reason. It is necessary to find a way to make the issue important, relevant and timely to the audience. It is important to know that if there is no reason that an audiences should listen to the speech, it is likely not appropriate to present to that audience.

Captivating the audience

A situation may arise were a speaker is forced to give a particular speech, and the audience is forced to listen. An example of this may be an HR person giving other employees a speech about safety in the workplace. The concepts mentioned in the previous sections can still be utilized, but they become a limited in their ability to engage the audience. The following tips can help to keep an audience interested in the topic.

Stories

People can only be bombarded with so many facts before they begin to tune a speaker out. Including stories (relevant to the topic) can help to relax the mood, provide humour and present useful information in an entertaining and attention grabbing way.

Make Connections

Sometimes it is easy to present a great deal of information and forget that the audience may not have experience in the topic and therefore cannot relate to it. It is important in all speeches, but especially technical ones, to try and connect the information to something relevant or known to the people in the audience.

For example, if a speaker were explaining that to run a 100W light bulb for 24 hours, 714 pounds of coal would need to be burnt. How many people know what 714 pounds of coal is? To help paint a picture one could determine the volume of that amount of coal and relate that to something physical that people can picture. In this example, 714 pounds of coal is approximately 500 L, which is enough to fill about half of a refrigerator!

Helping people visualize things keeps them engaged. When people can’t visualize something it becomes increasingly difficult to understand, which could lead to them no longer paying attention. In short, a good speaker knows what their audience can relate to and finds ways to relate their ideas to what the audience already knows.

Change is noticed

When a speech follows a consistent pattern it may become boring and the audience may lose interest. Surprises and changes can help to obtain and hold the audiences attention. Keeping the speech interesting is done in the preparation and planning stage and can include clear transitions, visual aids, or vocal variety. For more information about planning speeches, see the Delivery and Logos sections.

Identifying variations in your audience

Most audiences will not be homogeneous. For this reason, it is important to incorporate the aforementioned tips in a way that allows the speech to be inclusive for all members of the audience, as well as having a strong impact on the primary demographic of the audience.

Application of Theory

Audience adaptation is a skill that most people have naturally and use on a daily basis. For most interactions, people will try to adapt their conversation or body language to the audience they are surrounded by and it may or may not be intentional. When a speaker does not adapt to their audience, it is immediately evident and the speaker may risk accusations of being inappropriate or insensitive. In this section, the concepts previously mentioned will be applied to demonstrate how they can be used properly to tailor a message the audience.

Well-Defined Goal-Setting

The first step in preparing a speech is to define the exigence. After the exigence is thoroughly understood, the action can then be decided upon. This is so that one can tailor the action to the audience itself. The action needs to fit two criteria: it needs to address the exigence and be doable by the audience. For example, picture the following exigence: the university faces a financial deficit and budget cuts need to be made. If a university official was speaking to a group of students about this exigence, the proposed action could be to encourage students to take part in an online survey to determine the priorities of the students before deciding on how to cut costs. If that same official was speaking to various department heads, the proposed action could be very different. For example, the official could encourage the department heads to try and increase the lifespan of the resources used by those departments. Therefore, it is important to look at the problem from the audience’s perspective rather than having a solution in mind and trying to get the audience to participate in it. One approach relies on coincidence and the other on tactics.

Determining the needs of the audience (Using Bitzer)

After selecting an appropriate action for the audience, one must determine what the audience needs to hear in order to take said action. Much of this relies on the audience’s stance regarding the exigence. As mentioned in previous sections, audience predisposition is important when it comes to adapting a message to them. Using the concepts explained in Lloyd F. Bitzer’s “Functional Communication”, a brief summary of possible scenarios is outlined below.

Case 1: Audience agrees with the fact and the interest

In this case, the audience and the speaker more or less fully agree with the exigence presented. In such a case, the speaker need not allocate much time proving the facts or shifting the interests of the audience. In fact, doing so would only be important to establish ethos as briefly stating the facts will establish the speaker’s credibility, and briefly explaining the associated interests would establish the character of the speaker and create common ground with the audience. Therefore, the focus would need to be on the practical aspect of the speech such as enabling the audience, working around constraints or creating a sense of urgency so that they are prompted to take the action.

Case 2: Audience agrees with the fact, but disagrees with the interest

Once again, the audience agrees with the facts the speaker plans to present. However, they do not agree with the interest the speaker is suggesting. For example, most students are aware of the deficit currently faced by the university. However, some students may support program prioritization as an acceptable solution to the problem, while others may disagree with this notion. If one were trying to persuade students to support program prioritization to the latter demographic they would have to focus on explaining why the audience should adopt this interest before trying to persuade them to take a particular action, such as favourably responding to a survey regarding the matter.

Case 3: Audience agrees with the interest, but disagrees with the fact

In this case, the speaker needs to prove the proposed fact before the audience accepts the exigence. This means that a speaker may need to focus on quoting secondary sources and showing support from experts before the audience can be prompted to take action.

Case 4: Audience disagrees with both the fact and the interest

In this scenario, the audience fully rejects the speaker’s exigence. For example, a speaker might be trying to rally support for the building of nuclear power plants in Saskatchewan at a council meeting. The fact the speaker presents might be that nuclear power is cleaner than many other energy sources used in the province. The interest the speaker has could be that Saskatchewan isn’t utilizing nuclear power the way it should be. If the audience disagrees with both statements, then the speaker has the burden of establishing common ground with both the fact and the interest before enabling the audience. In this case, the speaker would need to back up his first claim by quoting studies in a manner that is understandable by the audience at hand. To establish a similar interest, the speaker could possibly focus on comparing areas that utilize nuclear power with those that do not.

Not only does the audiences’ predisposition to the exigence need to be addressed, but the audience’s background knowledge should also be taken into consideration. An audience that is very familiar with the topic do not need an explanation of the jargon used in a speech and will expect the speaker to develop a deeper argument that fully appreciates the complexity of the topic. If the audience has rudimentary knowledge regarding the topic would need a simpler argument. Furthermore, if the speaker is knows that the audience is already invested in remedying the exigence, then the action could be one that requires more effort than one for people who are not yet committed to solving the exigence at hand.

Tailoring the argument

Once a speaker has determined what the audience needs to hear in an argument, they need to decide how they will structure the argument in order to maximize the impact one has on an audience. This means looking at what parts of the argument are linked and determining which ideas need to be brought up first in order to allow the argument to naturally develop in the minds of the audience.

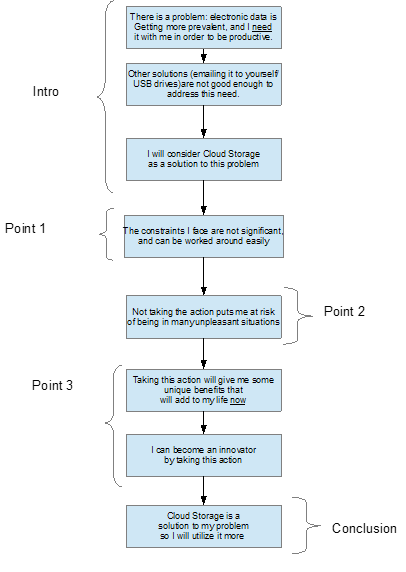

An example of such a structure can be seen in the figure below:

The flowchart shows the structure of a speech designed to encourage students to utilize cloud storage. Each step corresponds to a realization in the minds of the audience members.