Open Pedagogy as Open Student Projects

Joshua F. Beatty; Timothy C. Hartnett; Debra Kimok; and John McMahon

Authors

- Joshua F. Beatty, SUNY Plattsburgh

- Timothy C. Hartnett, SUNY Plattsburgh

- Debra Kimok, SUNY Plattsburgh

- John McMahon, SUNY Plattsburgh

Project Overview

Institution: SUNY Plattsburgh

Institution Type: public, liberal arts, undergraduate, postgraduate

Project Discipline: Political Science

Project Outcome: student-created library exhibit (physical and virtual)

Tools Used: Omeka, LibGuides

Resources Included in Chapter:

- Course Materials

- Virtual Exhibit Website

- Images

- Videos

2020 Preface

On April 9, 2020, between our final edits and publication, one of the co-authors, Tim Hartnett, passed away. Our chapter describes just what Tim meant to the And Still We Rise project, but cannot articulate his importance as colleague and friend. Tim was a musician and raconteur as well as a librarian, and brought the energy of the practiced performer to the academy’s milieu of introverts. For And Still We Rise, he drew the co-authors together; he had recruited Joshua to his position in the library, promoted Debra’s work in Special Collections and the College Archives, welcomed John at a new faculty reception, and early on saw the possibilities that could arise from John’s course, Debra’s archival holdings, and Joshua’s digital scholarship advocacy. Tim himself added a deep knowledge and lifelong commitment to Plattsburgh, exemplified by his labor chronicling the history of musicians and other performers who visited the college. We are grateful that Tim’s estate recognizes the importance of his work and that they are working with the authors to preserve and curate it for future generations.

A fuller appreciation of Tim’s life can be read in “A Meaningful Life,” from the Press-Republican newspaper.

—Joshua, Debra, & John

Introducing And Still We Rise

In Spring 2019, students at The State University of New York College at Plattsburgh (SUNY Plattsburgh) researched, designed, and built And Still We Rise: Celebrating Plattsburgh’s (Re)Discovery of Iconic Black Visitors (ASWR), an exhibit in the Feinberg Library on prominent Black political and cultural figures who had visited the college since the 1960s. The thirteen students in African-American Political Thought (Political Science 371), taught by Dr. John McMahon, researched in the college’s archives and secondary sources to curate photos, text and multimedia for physical and virtual exhibits.[1]

We wish to thank the students in the course, for without their ideas, work, and commitment, neither ASWR nor this book chapter would be possible: Marie Alcis, Jacob Baird, Kyla Church, Juntaro Hirose, Domenica Lacouture, Jenna Long, James McGarrity, Yukari Namihira, Keianna Noble, Nouran Noureldin, Alyssa Scott, Josh Shaw, and Kentaro Wada. The class’ work can be read on the digital version of ASWR available at Plattsburgh Rocks!, and a video of the opening ceremony led by students is available on YouTube: “And Still We Rise: Celebrating the (Re) Discovery of Plattsburgh’s Iconic Black Visitors.”

McMahon conceived of the project as putting into practice a vital component of Black political thought—that it is public in its call for transformation. This thought was not limited to academic books and articles alone, but rather insisted upon the connection of theory to practice and found its audience in speeches, pamphlets, music, film, and the like—all forms represented in the course material. McMahon wanted to design a project for the course that would affirm this element of Black political thought and present its own public challenge. He had also learned from colleagues at his previous institution (particularly from faculty women of color) who developed public-facing projects about race and racism and/or had students draw on campus collections to create a public exhibit.[2] Moreover, McMahon sought to use the course to engage with and provide political reflection upon campus conversations about race and racism. These concerns, in conjunction with his early dialogue with Librarian Timothy Hartnett, led to the initial ideas for the project. He would ask that students investigate the College Archives to find information about the Black political and cultural figures who had held events at SUNY Plattsburgh. The aim was to collectively create a public exhibit to be displayed in the library, presenting this political history to the campus as a whole and declaring that Black lives matter.

Two key ethical considerations undergird the project: the first is the pursuit of racial justice; the second, the embrace of open pedagogy. To understand how these informed the project, it is necessary to situate ASWR in its particular campus context. SUNY Plattsburgh is a rural, comprehensive state college with approximately 4900 undergraduate students and approximately 500 master’s students, with a faculty, staff, and student body that are predominantly white.[3] The percentage of students of color is, however, increasing, and several public racist incidents since 2015 have illuminated ongoing unresolved tensions on campus.[4] Black students regularly express feeling that they are treated as outsiders and their voices go unheard, while white students and employees are unaware of the city and college’s long history of people of color as residents and visitors. By documenting and publicizing the history of prominent Black visitors to the college, ASWR intended to remind the college community of this tradition and to support calls for a more intentional and sustained pursuit of racial justice on campus.

Open pedagogy is a compelling approach to engage this pursuit, in a context where approximately half of the class were students of color, and most of them had not had opportunities to perform open pedagogical work. ASWR was developed with an objective of engaging students by letting them work with primary source materials to create a public work that contributes to scholarly and community conversations, thus showing the students that their voice and work matters. As DeRosa and Robison (2017) emphasize, open pedagogy broadly seeks to empower students, and four principles of open pedagogy shaped the ASWR project. First, open pedagogies center students as reflective creators, curators, and sharers of knowledge who can develop a sense of educational autonomy (Cronin and MacLaren, 2018; De Rosa and Robison, 2017; Paskevicius, 2017). Second, open education practices emphasize active collaboration and social learning (Courous, 2010; DeRosa and Robison, 2017). Third, open pedagogy ought to be built into assignments themselves, for instance through Jhangiani’s five principles of open assignment design (2017, p. 272). Finally, open pedagogy turns student learning outward, to the public: it has the potential to “help our students find relevance in their work,” “contribute to the public good,” and create “engagement with the world outside the classroom” (DeRosa and Robison, 2017, p. 117). The end of the chapter returns to these principles in order to reflect on the project and its pedagogy.

Building and Presenting an Open Project on Black Campus Political History

Librarian-Faculty Collaboration in the Project’s Early Stages

McMahon conceived of the project as a result of a serendipitous conversation with Hartnett over lunch at a welcome event for new faculty in August 2018. The two discussed the African-American Political Thought course McMahon would be proposing to teach in the Spring 2019 semester. Hartnett, who was creating an archive of speakers and performers visiting campus from 1960-2000 for a project called Plattsburgh Rocks!, relayed to McMahon that he might be surprised to learn that important Black political and cultural figures like Nina Simone, Cornel West, and Dick Gregory had held events on campus.

This initial conversation proved fortuitous in multiple ways. As a librarian at the luncheon, Hartnett’s primary purpose was to informally raise new faculty’s awareness of librarian expertise and library resources. In doing so, he learned of McMahon’s subject expertise and teaching interests. Such communication is vital to informing librarians about faculty’s scholarship and teaching activities so as to optimize the library’s resources and services to better support faculty in their work.

So, what began as a chance, casual conversation over lunch developed into what would become a four-person collaboration on an open, student-driven project. Without Hartnett and McMahon sitting at the same table at a new faculty welcome lunch, this project likely would not have happened. This confirms the value of ongoing informal conversation between librarians and teaching faculty, to try to foster an environment where collaborative projects can germinate (Johnson, 2019).

A second conversation between McMahon and Hartnett at the library reference desk in October 2018 more directly launched the project itself. At that point, Hartnett shared a comprehensive spreadsheet documenting the record of campus cultural performances and political events, and McMahon began to ruminate over how to work with Hartnett—and with the other team members he would involve in the project, as discussed below—to actualize the potential of this resource. Hartnett saw an opportunity to connect the professor and his students with some uniquely relevant local materials contained in the library’s College Archives. This would best be accomplished through the help of Librarian Debra Kimok, who manages the College Archives. To further assist students, Hartnett prepared an online library research guide which included links to digitized archives of several of those materials.

In a subsequent email to Hartnett in December, McMahon expressed his desire to have students prepare a library display to publicly present their work. As the librarian in charge of exhibits, Hartnett was thrilled by this news. Given the nature of the students’ research and its contribution to telling the story of SUNY Plattsburgh’s campus history, Hartnett contemplated ways to make it more permanently and widely available to the public. It soon occurred to him that a digital exhibit might be the perfect means for doing so. He contacted Dr. Joshua Beatty, Digital Scholarship Librarian and also coincidentally the library’s liaison to the Political Science Department. Beatty quickly saw the value of and the possibilities for making ASWR an online exhibit.

Engaging Student Research and Discovery

Beatty, Hartnett, and Kimok provided students with an initial introduction to the College Archives during an early class session held in the library, with a follow-up formal research session led by Beatty. Outlines for these sessions as well as the timeline and requirements for student research can be found in the Appendix. Following this, all three librarians provided ongoing hands-on research assistance to students. The thirteen students in the course sought primary source materials that related to their chosen subjects. Guided by the project team, they found local and student newspaper and campus newsletter stories, yearbook pages, an “Artist Series” brochure, and archival photographs related to the campus visits of notable African American figures.

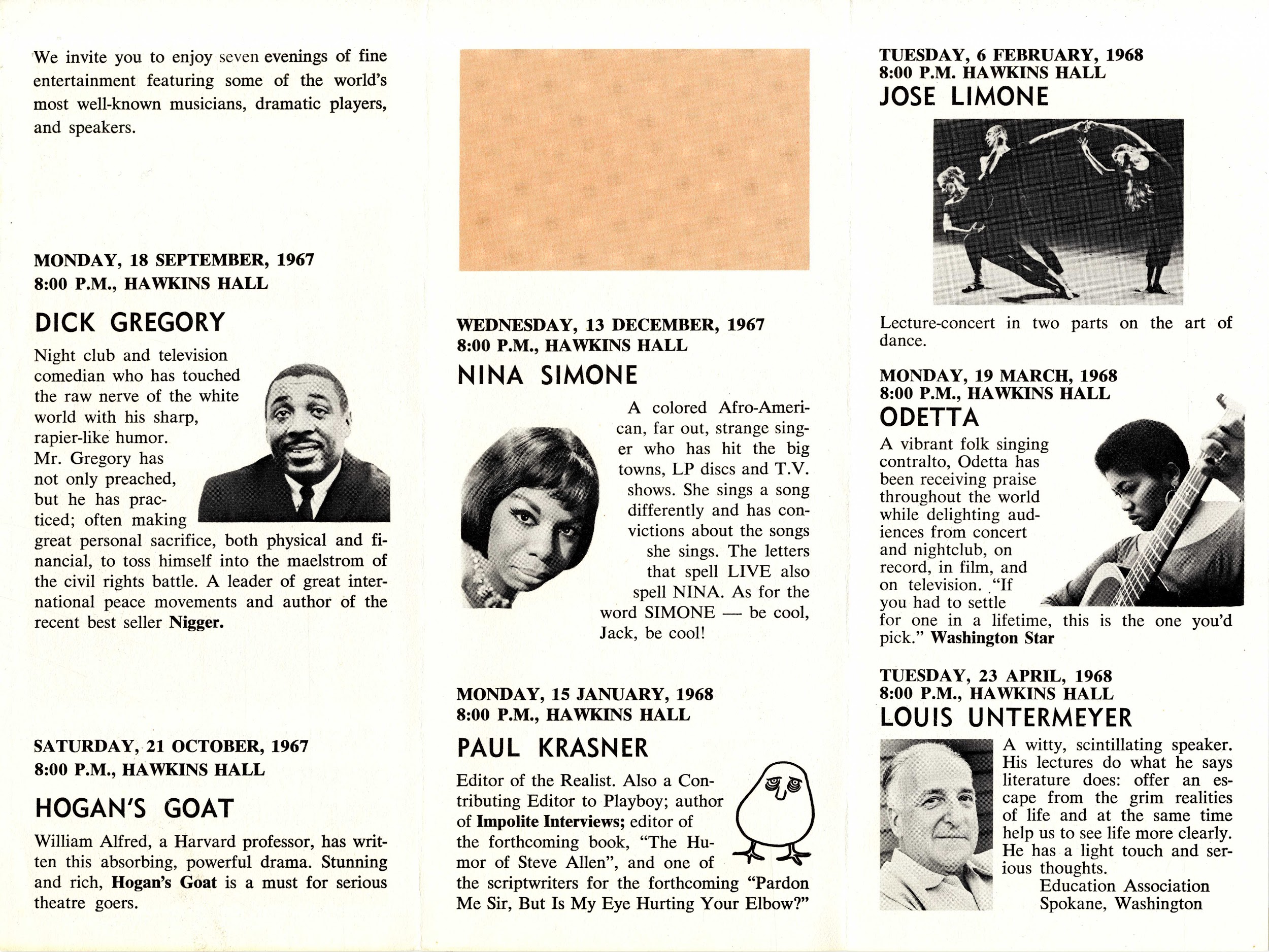

Student discovery in archives is frequently very exciting for them and is a valuable learning experience: “The use of archival material takes [students] into an environment different than a library and one with which they are not familiar. It also requires them to learn new techniques of discovery and creates a real sense of intimacy with people of a different time” (Matyn, 2000, p. 349). This kind of dynamic was most vividly illustrated when a student exclaimed upon opening a College Archives folder and seeing for the first time a 1967-1968 “Artist Series” brochure featuring a brief preview of Nina Simone’s upcoming performance along with a photo of Simone, pictured below. Moments such as these demonstrate the potential thrill of discovery student-researchers can experience, one that also generates original evidence and fosters a connection to the history of their college.

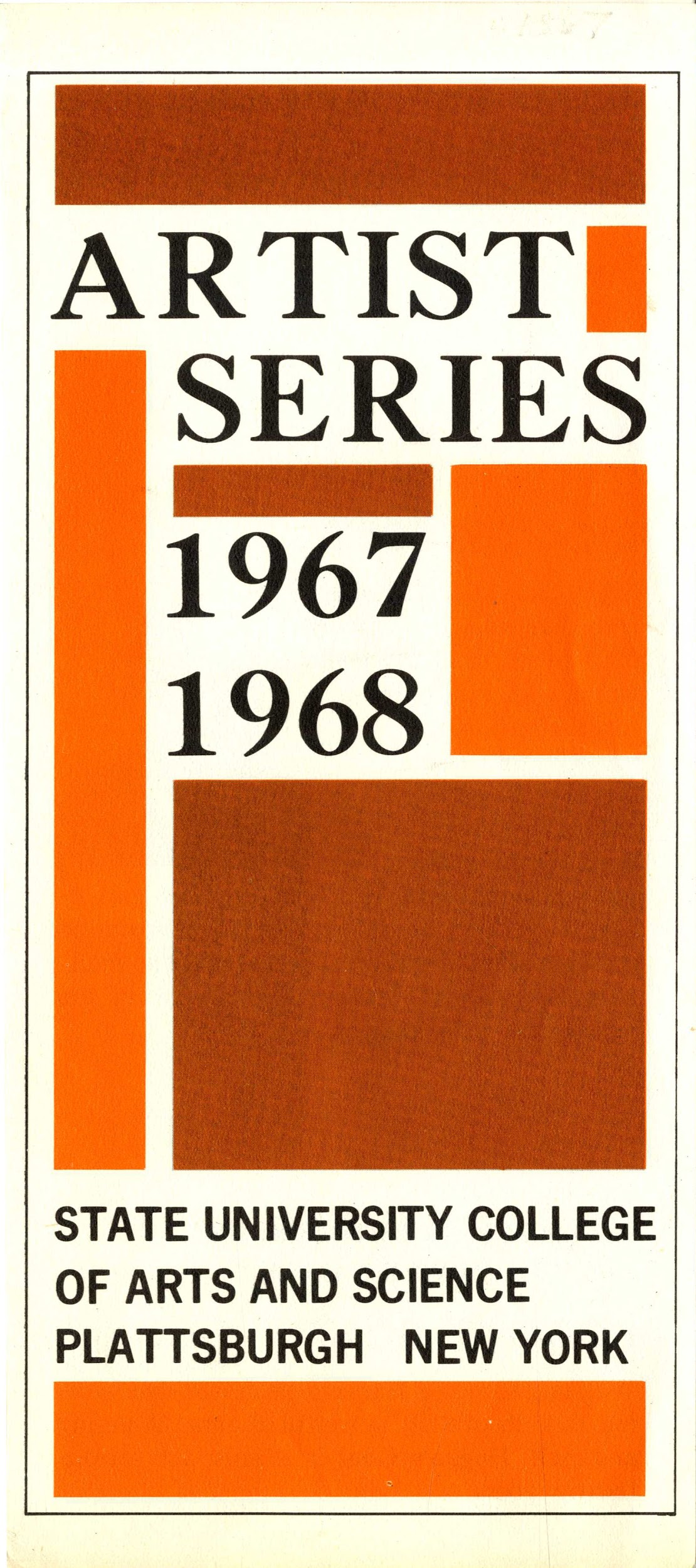

Figure 1

Front cover, “Artist Series 1967-1968” brochure.

Figure 2

Interior, “Artist Series 1967-1968” brochure

Students spent several weeks engaging in archival and scholarly research with a series of scaffolded assignments, detailed in the Appendix. They met obstacles along the way—above all a dearth of archival material on some of the individuals students had chosen to research, leading students to seek further assistance from members of the project team. McMahon slightly shifted the guidelines to leave more room for emphasizing the research subject’s general importance to Black politics and culture in addition to—and, in some cases, in place of—a strict focus on their event on campus. Ultimately, this process guided students toward the final form of their research, a 300–500 word account of the visit to SUNY Plattsburgh by each student’s research subject, text that would become the physical and digital exhibits.

Exhibiting in Two Forms, Physical and Digital

Physical Exhibit. McMahon and his students set May 1 as the date for unveiling the ASWR exhibit to the public. This provided ample lead time to publicize and plan for the opening. By early March, students, supervised by McMahon, had created promotional materials, including several variations of an exhibit poster, copy for a press release, a Facebook event page, and an Instagram account.[5]

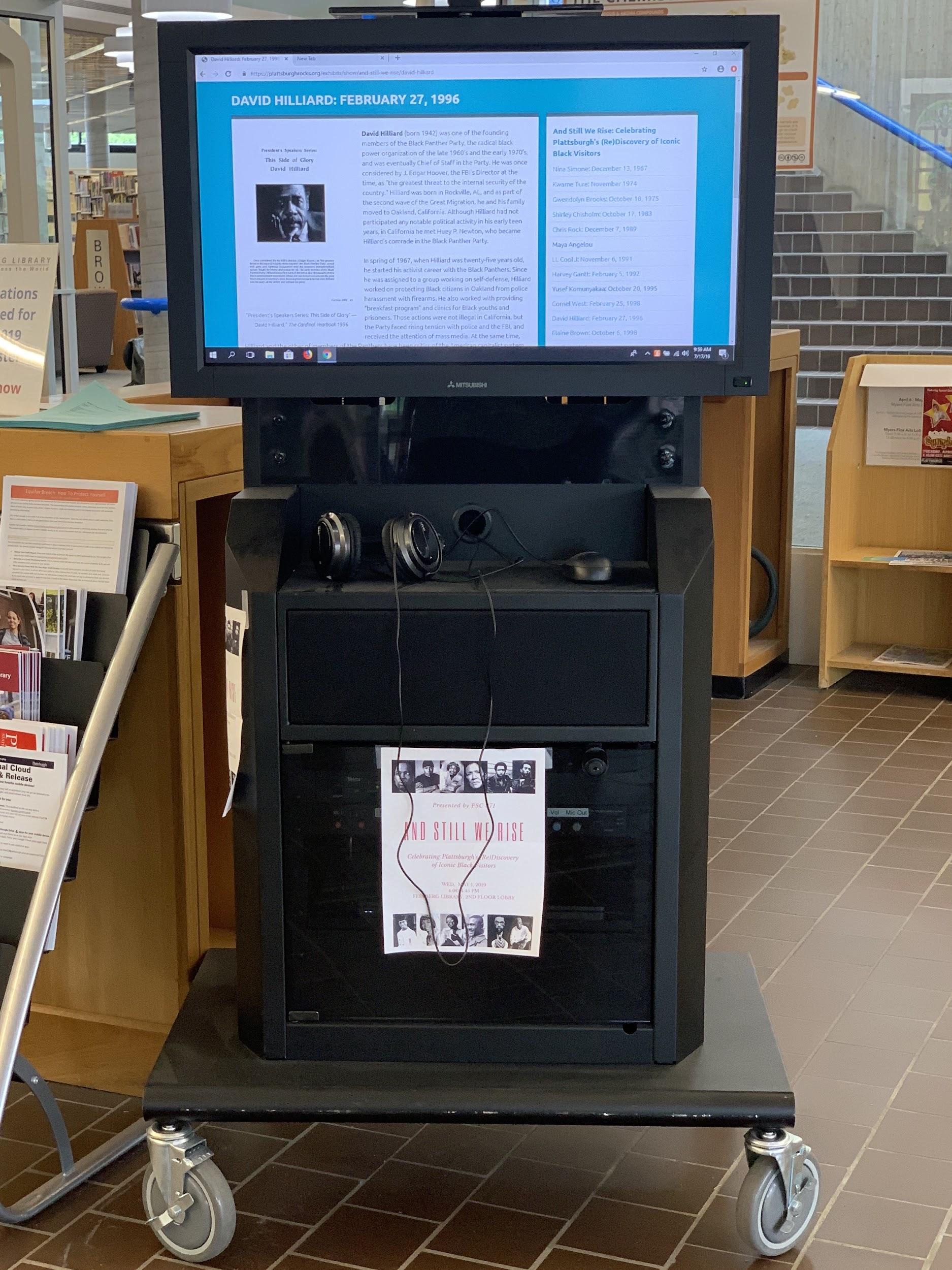

Hartnett reserved and readied the display case located in the main lobby of the library where the physical exhibit would be installed in late April. As the project progressed, students came up with ideas for enhancing the exhibit by adding a listening/viewing station at the display case for users to access audio and/or video files containing music, speeches, and interviews of the featured individuals. Hartnett consulted with campus Media Support Technician Eric Laesing about how best to do this. Given space and infrastructure limitations, they decided to set up a dedicated media station with headphones across the lobby where visitors could listen to embedded music clips and view embedded videos selected by students from a variety of Internet sources on a large screen monitor with headphones, pictured below.

Digital Exhibit. At this point, Beatty offered to create a digital exhibit that would contain not only the audio and video files, but the text and photographs curated by the students. The digital exhibit could replace a simple list of video and audio files on the media station in the library lobby, as well as be accessible beyond the library walls. The digital exhibit was not part of McMahon’s original vision for the project, but he quickly realized that it would enable the students’ work to live on beyond the lifespan of the display in the library lobby and would provide access to those unable to visit the library.

The team considered whether ASWR should be a standalone site or a part of Hartnett’s larger Plattsburgh Rocks! digital project. Plattsburgh Rocks! was primarily intended to chronicle the history of musical performances at SUNY Plattsburgh. It had been built by Hartnett and Beatty using the digital asset management and digital exhibit software Omeka Classic. Plattsburgh Rocks! was a work in progress, serving more as a holding place for a handful of posters, news articles, and audio interviews that had been digitized. At this point, the team still considered the digital version as a minor addition to the physical exhibit and opening ceremony. As such, they decided to add ASWR as a collection of items and accompanying exhibit to Plattsburgh Rocks!, but to give ASWR its own visual styling via a different Omeka theme to distinguish it from the rest of the site.

Students collected content from the College Archives and from online databases, notably New York Historical Newspapers. College Archives staff, under Kimok’s direction, digitized photographs and documents identified by students for use in the exhibit. For the design of the Omeka site, the team adapted the off-the-shelf “Seasons” theme with fonts that matched or mimicked those used in the physical exhibit.

Figure 3

Digital exhibit page featuring Shirley Chisholm photograph taken at SUNY Plattsburgh.

Figure 4

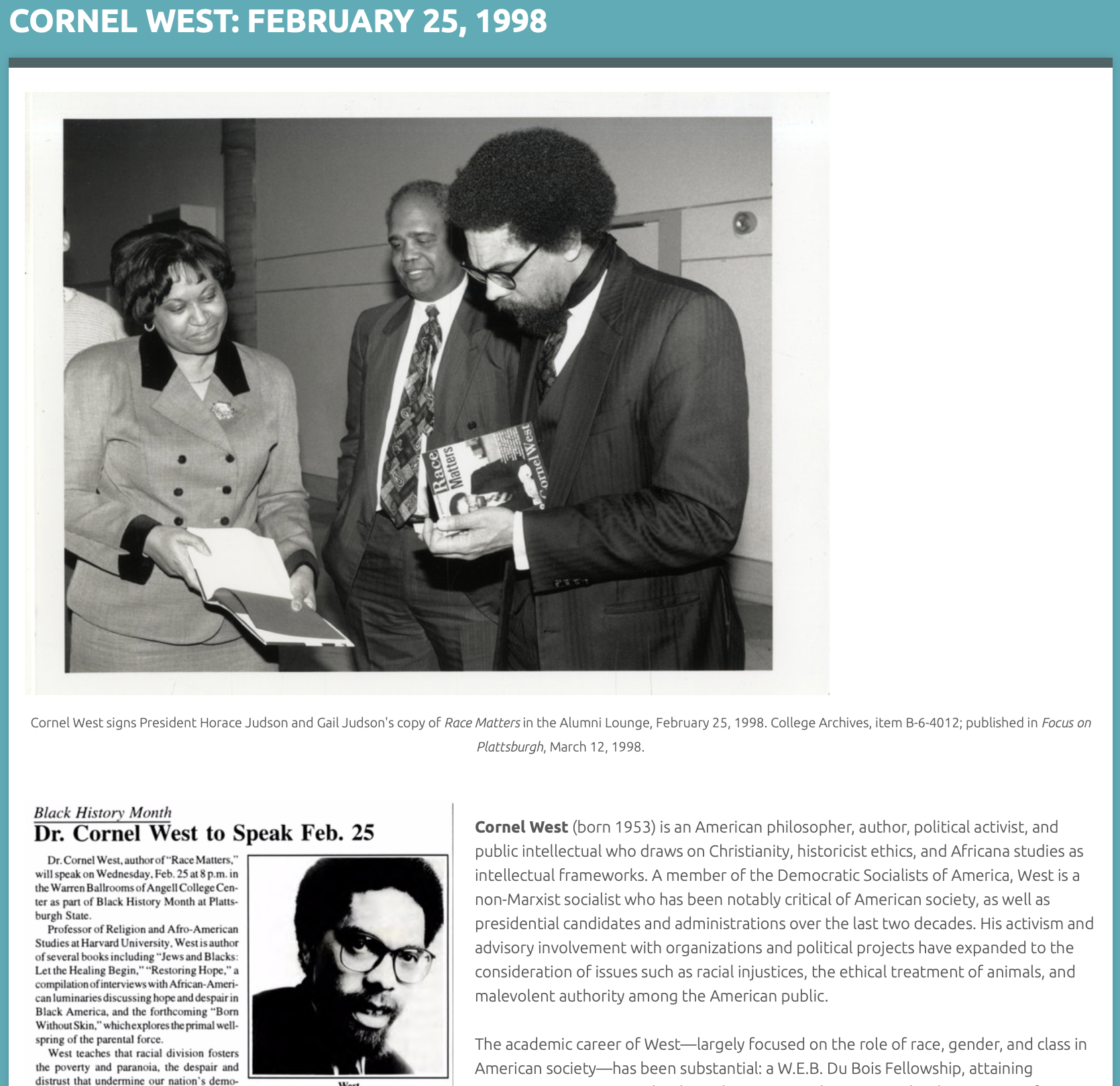

Digital exhibit page featuring Cornel West photograph taken at SUNY Plattsburgh

The architecture of the digital exhibit involved creating a separate event item for each performance covered, then adding each news story, publicity piece, video, or audio file selected by the students as an item connected to the event using Dublin Core relationship metadata. Initially the team planned to produce the digital exhibit after the semester was over, but as the project gathered momentum, McMahon realized it was important to be able to point people to a website for publicity beforehand and for news reports afterwards. Given more time, the team might have split And Still We Rise from Plattsburgh Rocks! to its own website with its own domain name. In the end, McMahon created a short URL (tinyurl.com/plattsburghrise) pointing to the exhibit on Plattsburgh Rocks! so that the team could distribute an easy-to-remember web address.

Beatty added pictures and videos from the opening event following the exhibit opening. The digital exhibit, via a dedicated computer and media cart, remained in the library lobby near the physical exhibit through the summer of 2019. It continues to be accessible online, and future versions of the course may add to it.

At the end of the project, the team assessed the digital exhibit and reflected on changes we would make in future iterations. We would purchase a domain name well beforehand and set up the project in such a way as to make it easy to use that domain name even if it continued to be hosted on the Plattsburgh Rocks! server. The best way of doing this might be to convert Plattsburgh Rocks! from Omeka Classic to Omeka S, a newer version intended for institutional collections of digital objects that can then be used in many different exhibits. Plattsburgh Rocks! and a new And Still We Rise domain name could then both point to exhibits built in a single Omeka S instance. We would also like to incorporate students into the design and building of the digital project, rather than just have faculty or librarians build an exhibit based on students’ work. One team within the class with interest and aptitude in digital scholarship could build the digital exhibit, while another team could concentrate on the physical, incorporating open design principles into their work. These students could then make design and organizational decisions from the start, as their peers would with the physical exhibit.

Exhibit Opening. McMahon and his students prepared the program for the May 1 opening, which included remarks by Hartnett, the Dean of the School of Arts & Sciences Andrew Buckser, McMahon, and six of his students. Hartnett arranged for a speaker’s podium, seating, and a professional sound system to create a more formal ambience befitting the importance of the event. Hartnett also enlisted Matt Rist, a library student-employee skilled in videography, to record the program. The Dean of Library, Information, and Technology Services Holly Heller-Ross provided funds for refreshments for attendees. There was local newspaper coverage prior to the opening and Mountain Lake PBS attended the event to shoot live footage of the program and interview participants and attendees afterward. The size of the crowd exceeded expectations. There were a significant number of community members in attendance and an unexpectedly large turnout by faculty and administrators as well. From the perspective of those of us who have been on campus the longest, the ASWR project was one of the most visible events on campus featuring the work of a single class.

Figure 5

Photograph of exhibit, lobby of Feinberg Library, SUNY Plattsburgh.

Figure 6

Media cart displaying digital exhibit, Feinberg Library, SUNY Plattsburgh.

Reflecting on ASWR and Open Pedagogies

Pedagogically, the project works to enact several motivating principles of open education. Important for us is that open pedagogy does not just implicate specific curricula, assignments, and resources, but also carries with it values (Cronin and MacLaren, 2018), such as those identified in the introduction. This project intertwined specific practices with a broader mission. ASWR facilitated students’ development as knowledge creators, researchers, and public authorities on the subject. The project also instantiated open practices and served a broader political and social purpose on campus.

More specifically, in terms of the first principle articulated in the introduction, that open pedagogy can facilitate student educational autonomy, ASWR enabled students to exercise such autonomy in their self-directed research, public writing, and presentation about a prominent figure from Black campus history. Students chose their figures, engaged in the research, and wrote the exhibit text for their figures. The second principle involved active collaboration and social learning. The project fostered this mode of learning through the collective decision-making processes about the exhibit name, display, social media, and so on, and also through regular check-ins and class-wide brainstorming sessions about the research and exhibit. Additionally, ASWR provides an example of how the elements of open pedagogy-driven assignment design in the third principle identified in the introduction can be translated into public-facing practice.

In retrospect, what became most important was the fourth identified principle, that open pedagogy orients student scholarship to public audiences and to public good. In its conception, its process, and especially its exhibit and open presentation, ASWR brought what students had been learning in the classroom to the campus community—and beyond, with the online exhibit—as a project for racial justice. In this, the authors took inspiration from the work at a similarly-situated comprehensive college by Risam, Snow, and Edwards (2017). The authors thus hope the project at least partially realizes the purpose that Smyth et al. identify for open educational practices to “support social transformation, sharing and co-creation of knowledge in fully open ecosystems, where benefit for social good is expected” (2016, p. 211). In the most optimistic interpretation of ASWR, it involved the sharing of instructor, librarian, archivist, and student knowledges for the co-creation of an open resource that positioned students as independent researchers and that can, at the very least on campus, contribute to racial justice projects of social good.

Libraries have been at the forefront of the open pedagogy movement within colleges and universities (Hensley and Bell, 2017; Walz, 2017). At SUNY Plattsburgh, a small group of interested librarians—Beatty, Kimok, and OER Librarian Malina Thiede—had been promoting services related to open pedagogy, such as digital scholarship, student publishing, and Open Educational Resources (OER), while encouraging the library to give these services a more prominent place. The librarians’ interest in open pedagogy stemmed from a belief that one of the best ways to engage students with their education is to show them that the work they do matters. By giving students an opportunity to make their work public-facing, open pedagogy initiatives allow students to directly engage the public and to make a difference in the larger world.

Librarians run digital services necessary to open pedagogy, but the content expertise of teaching faculty and students is essential to making open materials meaningful. Plattsburgh librarians had identified possible avenues that would be most effective for open pedagogical initiatives, with an eye towards the college’s recent history of racial tensions. Plattsburgh librarians had identified the College Archives as a repository of materials that could illuminate the college’s racial history. Students could potentially tell the stories of members of the college community who have been overlooked, especially faculty, staff, and students of color—perhaps even recording, archiving, and publishing oral histories. Finally, librarians might work with teaching faculty or college organizations to make visible the intellectual work of students from historically underrepresented groups.

The ASWR project became the ideal project to demonstrate how the library could support teaching faculty in open pedagogical practices because it was developed by students and directly confronted the college’s recent history. The students developed new research skills, specifically how to search for information in our College Archives and in online newspapers. As detailed in the Appendix, students completed a longer essay incorporating the research completed for the exhibit itself. They gained a better understanding of the history of their college and their connection to it, creating a greater sense of their inclusion in and attachment to that history. This connection enabled students to “see that they are part of a continually evolving life of a university” as a result of engaging “archival records” (Matyn 2000, p. 351). Additional evidence is found in a 2010 study of faculty use of archival materials in their teaching, which reveals that “faculty who have brought undergraduates into an archives or special collections department to let students work with original documents report that students are powerfully moved by working with authentic materials” (Malkmus 2010, p. 414).

The ASWR students benefited from working with primary source materials. Using finding aids to identify archival materials that had been collected and processed, they uncovered a documentary history to bring to a broad campus awareness. This discovery had a visceral impact on the students and gave them a connection to an important aspect of the college’s history. The students created the content for a resource that now is part of the campus historical record and enriches the meaning of the documents in the archival boxes and the news stories online. Moreover, the ASWR project empowered the students in several ways, one of which was to draw on the past to speak to the present and the future.

The team hopes that this project spurs further reflection and research on the possibilities of open pedagogies in the field of political science. Extant literature on openness in the discipline is limited to research on students’ reception of and learning with the use of Open Educational Resources (OER), with two studies finding mixed results (Brandle 2018; Lawrence and Lester 2018).[6] However, much of the scholarship on open pedagogy emphasizes its political mission. For instance, Kalir (2018) argues that open pedagogies are concerned with issues of equity, power, and access, while Cronin and MacLaren contend that critical digital pedagogies that frequently inform open educational practices focus on the “potential of open practices” to “function as a form of resistance to inequitable power relations within and outside of educational institutions” (2018, p. 4). These are political questions that the field of political science finds itself uniquely situated to address. At the same time, the development of open pedagogies in the discipline would be likely to help achieve many of its pedagogical aims, such as teaching democratic engagement (Sloam 2008) or political knowledge production (McMahon 2019a) through active learning practices.

Finally, the team envisioned this project as a way to make visible Black history, politics, culture and campus life. As written in the text introducing the exhibit:

At a time when our campus—and, to be sure, the country more broadly—is compelled to reexamine its relationship to antiblack racism, And Still We Rise testifies to Black pasts, presents, and possible futures at SUNY Plattsburgh. It can constitute, we hope, one impetus among many for an active, self-reflective pursuit of racial and social justice, a pursuit grounded in Black experiences. This is an exhibit that centers Black life on campus and that asserts that Black lives do matter. As you engage with the histories presented here, we invite you to consider the visions and dreams for the events, conversations, commitments, actions, collectivities, and imaginations that And Still We Rise can impart (McMahon, 2019b).

The openness of the project enhanced its commitments to racial justice, emphasizing its collaborative processes, cultivation of student voice, and public nature. In doing this, the project not only centered Black life on campus, but also demonstrated the potential for curriculum and assignments—and for student-librarian-faculty collaboration—to do work on campus that seeks to further racial justice.

Conclusion: Creating, not Consuming

As an open project with the motivating principles discussed in the previous section, we are confident our approach can be effectively adapted by librarians and teaching faculty at other institutions. Librarians and teaching faculty should anticipate that many resources exist in the archives and special collections of their institutions, which could be used to enhance and support courses and projects. Additionally, other campuses should consider building a similar kind of archive of speakers and performers for the purpose of developing course and campus projects. Focusing on materials such as those forming the basis of ASWR would enable collaborators to develop projects and exhibits centering Black history and politics on campus. These archival resources could also be a foundation for similar projects engaging campus histories of particular topics such as environmental action, political activism, or music performances, or of other marginalized groups and identities. Broadly, proactive collection and cataloguing of materials created by marginalized social groups on campus supports a wide range of pedagogical and ethical purposes, and in all of the advice offered in this paragraph, intentional and active collaborative efforts are necessary.

In all of these possibilities, open pedagogy paired with commitments to social justice and librarian-faculty collaboration enables students to develop their skills and their voices as researchers and experts in their own right. Students creating, rather than merely consuming, open public scholarship proves particularly vital for such flourishing. Through ASWR and the pedagogical commitments underpinning it, students could articulate their own voices as researchers, collaboratively investigating campus history in pursuit of public education (in multiple senses of the term) and racial justice. Such is the promise of this type of learning in its future iterations at SUNY Plattsburgh and beyond.

References

Brandle, S. M. (2018). Opening up to OERs: Electronic original sourcebook versus traditional textbook in the Introduction to American Government course. Journal of Political Science Education, 14(4), 535–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2017.1420482

Couros, A. (2010). Developing personal learning networks for open and social learning. In G. Veletsianos (Ed.), Emerging technologies in distance education (pp. 109–128). UBC Press.

Cronin, C., & MacLaren, I. (2018). Conceptualising OEP: A review of theoretical and empirical literature in Open Educational Practices. Open Praxis, 10(2), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.10.2.825

DeRosa, R., & Robison, S. (2017). From OER to Open Pedagogy: Harnessing the power of open. In R. S. Jhangiani & R. Biswas-Diener (Eds.), Open: The philosophy and practices that are revolutionizing education and science (pp. 115–124). https://doi.org/10.5334/bbc.i

Hensley, M. K., & Bell, S. J. (2017). Digital scholarship as a learning center in the library: Building relationships and educational initiatives. College & Research Libraries News, 78(3), 155–158. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.78.3.9638

Jhangiani, R. S. (2017). Open as Default: The future of education and scholarship. In R. S. Jhangiani & R. Biswas-Diener (Eds.), Open: The philosophy and practices that are revolutionizing education and science (pp. 267–279). https://doi.org/10.5334/bbc.i

Johnson, A. M. (2019). Connections, conversations, and visibility: How the work of academic reference and liaison librarians is evolving. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 58(2), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.58.2.6929

Kalir, J. H. (2018). Equity-oriented design in open education. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 35(5), 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-06-2018-0070

Lawrence, C. N., & Lester, J. A. (2018). Evaluating the effectiveness of adopting open educational resources in an introductory American Government course. Journal of Political Science Education, 14(4), 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2017.1422739

Malkmus, D. (2010). “Old stuff” for new teaching methods: Outreach to history faculty teaching with primary sources. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 10(4), 413–435. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2010.0008

Matyn, M. J. (2000). Getting undergraduates to seek primary sources in archives. The History Teacher, 33(3), 349–355. https://doi.org/10.2307/495032

McMahon, J. (2019a). Producing political knowledge: Students as podcasters in the political science classroom. Journal of Political Science Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2019.1640121

McMahon, J. (2019b, April). And still we rise: Celebrating Plattsburgh’s (re)discovery of iconic Black visitors. http://plattsburghrocks.org/exhibits/show/and-still-we-rise

Paskevicius, M. (2017). Conceptualizing open educational practices through the lens of constructive alignment. Open Praxis, 9(2), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.9.2.519

Risam, R., Snow, J., & Edwards, S. (2017). Building an ethical digital humanities community: Librarian, faculty, and student collaboration. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 24(2–4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2017.1337530

Rumsey, A. S. (2011). New-model scholarly communication: Road map for change. Scholarly Communication Institute, University of Virginia.

Sloam, J. (2008). Teaching Democracy: The role of political science education. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 10(3), 509–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856x.2008.00332.x

Smyth, R., Bossu, C., & Stagg, A. (2016). Toward an open empowered learning model of pedagogy in higher education. In S. Reushle, A. Antonio, & M. Keppell (Eds.), Open learning and formal credentialing in higher education: Curriculum models and institutional policies (pp. 205–222). IGI Global.

Walz, A. (2017). A library viewpoint: Exploring open educational practices. In R. Jhangiani & R. Biswas-Diener (Eds.), Open: The philosophy and practices that are revolutionizing education and science (pp. 147–162).

Contact Information

Author Joshua F. Beatty may be contacted at joshua.beatty@plattsburgh.edu. Author Debra Kimok may be contacted at kimokdm@plattsburgh.edu. Author John McMahon may be contacted at jmcma004@plattsburgh.edu.

Feedback, suggestions, or conversation about this chapter may be shared via our Rebus Community Discussion Page.

Appendix: And Still We Rise assignments, timelines and lesson plans

Outline for Library and Archives Information Session, 2/11/19

- Introductions

- Overview of the multiple roles Debra, Tim, and Joshua will be playing to support the project this semester

- Overview of resources

- Cardinal Points

- article(s)/photo(s) about event

- What else was happening on campus in the month before and after?

- Press-Republican

- Photo collections

- What to do if there is *not* much info about the person they’ve chosen?! → (e)

- Other resources

- People: seeing if it’s possible to track down writer and/or photographer, etc.

- NYS Historic Newspapers, etc.

- speaking/performing tour – what did they talk about in other places, etc.

- Cardinal Points

- Practical considerations

- Accessing the archives

- Relevant technology and devices

- Hi-res scanning

- Preview of what’s come with session with Joshua next month

- Exhibit

- 2nd floor displays cases

- Online

- Any logistics worth discussing now?

- Closing – why, from standpoint of Debra, Joshua, and Tim, this is an interesting, meaningful, and/or important project!

Outline for Research and Database Session, 3/13/19

- Review: what are primary sources?

- Different kinds of primary sources

- Text, images, audio, or video?

- Printed or handwritten?

- Specific databases to search:

- New York Historical Newspapers

- College yearbooks, in New York Heritage

- Hands-on searching, with librarians guiding when asked

- Encourage students to share findings throughout class

Requirements for Exhibit Research

For your research subject, you are required to complete the following research in SUNY Plattsburgh and NYS archives:

- Find and read relevant Cardinal Points, Press-Republican, and any other local articles about the visit to campus

- Look through Cardinal Points archives one month before and after the event (to get a sense of campus political and social climate and events, etc.)

- Search for and identify images (one photo + one poster/flyer, or two photos) for possible inclusion in the display

- Cardinal Points and/or College and/or P-R preferred, but can search for use-able other images from the time period if necessary

- EITHER: a) attempt to contact at least three people possibly connected to the event (writer(s)/photographer(s), SA President/Activities officer, campus figures, etc.) OR b) research other speaking/performing engagements of your subject around the time period they came to Plattsburgh

- For (b), one can assume that the subject visited Plattsburgh as part of some kind of tour, and thus it can be worthwhile to examine other possible stops on the tour, especially in the region and in New York state.

Required elements for the exhibit display:

- Text: write-up summarizing a) context of person’s importance to Black politics and culture, and to American politics and culture more broadly; b) relevant information about their activities around the time of their visit; and c) information regarding their visit to SUNY Plattsburgh

- Individuals: 2-3 short paragraphs; pairs, 3-5 short paragraphs

- You will (hopefully) develop more research and information than there will be room for in the exhibit itself. Part of the writing process for the display text will be deciding what is most essential to achieve those three goals.

- Draft text for exhibit will be due at the start of class on 4/22, for a peer review workshop on that day.

- 1-2 photos, posters, etc., preferably of visit to Plattsburgh, but other images okay

Timeline for Exhibit Research

- Monday, 3/25: One to two sentences to put on And Still We Rise social media + link to one image of your subject (can be from anywhere)

- Wednesday, 3/27: Summary (about 100 words) of available archival material on your research subject

- Include names of any alumni you want to possibly contact + any other special requests

- Monday 4/8: Identification of images from Cardinal Points, Press-Republican, yearbook archives for inclusion in display

- include identifying information (for instance, the date of the Cardinal Points issue + page number of photo)

- If no photos available, choose online image(s) of that person from around the time of their visit to campus, including identifying information for the photo source

- Monday 4/22: Text for exhibit display (2-3 short paragraphs for individuals, 3-4 short paragraphs for pairs)

- Bring to class for peer review

- Display text should include a) context of person’s importance to Black politics and culture, and to American politics and culture more broadly; b) relevant information about their activities around the time of their visit; and c) information regarding their visit to SUNY Plattsburgh – what they spoke about/performed, campus climate and political debates, etc.

- Wednesday 4/24: FINAL text for exhibit display

Requirements and Timeline for Final Research Paper

Your final paper will be an essay of approximately 2500 words on the political thought of your research subject. Your paper will include: a) analysis of central political themes in the work of your subject, including an interpretation of one or more key essays, books, articles, songs, poems, etc.; b) historical context about the political activities of your subject; c) examination of how your subject relates to the traditions of Black political thought—here, you should discuss relevant themes and thinkers from the class.

- Formatting requirements will be the same as for the midterm essay assignment

- You must cite at least seven sources that are not part of the class (at least three of these must be written by someone other than your research subject), and also must cite at least two sources from the course.

- You will be required to use American Political Science Association (APSA) citation formatting. Information will be provided about APSA style.

- Intermediate assignments

- Wednesday 4/3: List of 12 possible sources

- Monday 5/6: Outline/planning document, minimum 500 words

- We wish to thank Holly Heller-Ross, Dean of Library Information and Technology Services at SUNY Plattsburgh, and we are grateful for the support and contributions of Mike Burgess, Eric Laessig, and Sydni Reubin to the project. ↵

- Here, McMahon would like to thank Debra Majeed, M. Shadee Malaklou, Catherine Orr, Nicole Truesdell, Kylie Quave, Jesse Carr, and other previous colleagues who have taught him a great deal about the vital need to work with one’s students to engage campus on issues of race and racism beyond the walls of the classroom itself. ↵

- According to institutional data available to the authors, White, non-Hispanic domestic students comprised 62.9% of the SUNY Plattsburgh undergraduate student body in Fall 2019, compared to 12% domestic Hispanic/Latino students, 10.3% domestic Black/African American students, and 6.3% international students, among other identifications. In Fall 2009, Hispanic/Latino students and Black/African American students constituted 4.9% and 4.6% of the undergraduate student body, respectively. In 2014, Hispanic/Latino domestic students made up 6.5% of the undergraduate population, and 9.5% of undergraduates were Black/African American. ↵

- In fall 2015, the student newspaper, Cardinal Points, printed a racist cartoon on its front page. Initial anger was directed at the editors and artist but soon widened into a condemnation of racism across the campus: "For hundreds at SUNY Plattsburgh, cartoon reveals systemic racism." In January 2018, a white student posted a picture to Snapchat with a caption that referenced lynching. Students of color pointed out, correctly, that little had been done to address structural racism at the college after the prior incident: "Plattsburgh, Keene struggle with aftershocks of racist joke." ↵

- The name was developed by students drawing on Maya Angelou’s groundbreaking poem, “Still I Rise,” shifting it to “And Still We Rise” to emphasize the collectivity generated by the class and on campus through the project, and also to draw on themes of resilience and resistance to racism and racist incidents on campus. Hartnett’s initial research indicated that Angelou came to campus, but shortly before the exhibit, he discovered that two scheduled events had to be cancelled. The exhibit website provides further information regarding Angelou. ↵

- Both articles state that using OER in introductory American government classes did not improve student success measured in terms of student learning outcomes. However, Brandle noted that using the OER book led to pedagogical development and a meaningful course redesign, while Lawrence and Lester identify increased affordability and access to course texts as a benefit of OER. ↵

.keep {

page-break-inside: avoid;

float: top unless-fit;

}

.keep1 {

page-break-inside: avoid;

}

table, tr, th {

page-break-inside: auto; }

.textbox.key-takeaways p {

background: #c5dbcb!important;

}

.textbox.key-takeaways .textbox__content {

background: #c5dbcb!important;

}

.textbox.key-takeaways, .key-takeaways.bcc-box, .bcc-success {

background: #c5dbcb!important;

padding: 0;

margin-bottom: 1.35em;

margin-left: 0;

margin-right: 0;

border-radius: 0;

border-style: none;

border-width: 0;

color: #000;

page-break-inside: auto;}

.textbox.key-takeaways h3, .key-takeaways.bcc-box h3, .bcc-success h3{

color: #ffffff!important;

}

.textbox.learning-objectives h3, .learning-objectives.bcc-box h3, .bcc-highlight h3,

.textbox.key-takeaways h3, .key-takeaways.bcc-box h3, .bcc-success h3,

.textbox.exercises h3, .exercises.bcc-box h3, .bcc-info h3,

.textbox.examples h3, .examples.bcc-box h3,

.textbox.learning-objectives h2, .learning-objectives.bcc-box h2, .bcc-highlight h2,

.textbox.key-takeaways h2, .key-takeaways.bcc-box h2, .bcc-success h2,

.textbox.exercises h2, .exercises.bcc-box h2, .bcc-info h2,

.textbox.examples h2, .examples.bcc-box h2, .textbox__title {

padding: 0.5em 0.5em 0.5em 1em!important;

margin: -0.5em -0.5em -0.5em -1em!important;}

.textbox.textbox--learning-objectives .textbox__header, .textbox--learning-objectives.bcc-box .textbox__header, .textbox.textbox--key-takeaways .textbox__header, .textbox--key-takeaways.bcc-box .textbox__header, .textbox.textbox--examples .textbox__header, .textbox--examples.bcc-box .textbox__header,.textbox.textbox--exercises .textbox__header, .textbox--exercises.bcc-box .textbox__header, {

padding: 0.5em 0.5em 0.5em 1em!important;

}

#title-page .author::before {

content: "Edited by "!important;

}

img.tall {

max-height: 70%;

page-break-before: avoid;}

.front-matter a, .part a, .chapter a, .back-matter a {

color: #0F57A3;

}

.front-matter .wp-caption figcaption, .part .wp-caption figcaption, .chapter .wp-caption figcaption, .back-matter .wp-caption figcaption, .front-matter .wp-caption .wp-caption-text, .part .wp-caption .wp-caption-text, .chapter .wp-caption .wp-caption-text, .back-matter .wp-caption .wp-caption-text {

font-style: normal;

}

.front-matter a:hover, .part a:hover, .chapter a:hover, .back-matter a:hover {

color: #3a11b2;

}

.front-matter a:visited, .part a:visited, .chapter a:visited, .back-matter a:visited {

color: #7D3F7D;

}

Making a historical literary text more accessible and familiar by connecting the text to current events, issues, media, or theory. Radical familiarity is a form of critical thinking that allows students to meet an “old” or different type of text on well-known or common ground.