Open Pedagogy as Textbook Replacement

Dennis E. Schell; Dorinne E. Banks; and Neringa Liutkaite

Authors

- Dennis E. Schell, The George Washington University

- Dorinne E. Banks, The George Washington University

- Neringa Liutikaite, The George Washington University

Project Overview

Institution: The George Washington University

Institution Type: private, research, undergraduate, postgraduate

Project Discipline: Psychology

Project Outcome: Student Feedback Survey and Impact Analysis

Tools Used: OpenStax

Resources Included in Chapter:

- Student Survey Questionnaire

- Faculty Email Template

- OER Promotional Flyer

- Supplementary Sources for OpenStax Psychology

- Timeline for OER Textbook Adoption

- Course Goals

Authors’ Note

The authors thank Adam Kemper for his assistance in developing the comprehensive list of topics covered in the OpenStax general psychology textbook. The authors also thank Erin Pontius, who helped provide links to freely-available educational videos online and library subscription content.

Introduction

The George Washington University (GWU) Libraries’ OER Team was formed in 2016 in response to the rising cost of college textbooks and a need for advocacy for affordable course materials on campus. Building partnerships with campus stakeholders and aligning the OER initiative around college affordability, student success, and the student experience at our institution were key to gaining traction. The focus of this chapter is a detailed description of the process of switching from an expensive, required general psychology textbook to freely-available open course materials. Collaboration between the faculty member, OER Team librarians, and students made this project unique. This chapter is organized around the five strategic phases we used to adopt open course materials:

- Phase One: raising awareness of affordable course materials at GWU

- Phase Two: understanding students’ perceptions and use of a textbook in general psychology

- Phase Three: reviewing the affordable options for general psychology

- Phase Four: adoption of the OpenStax general psychology textbook

- Phase Five: implementation and evaluation of student satisfaction of the OpenStax general psychology textbook

Effect of High Cost of College Textbooks on Students, Faculty, and Librarians

Affordability of college course materials is a major concern for many undergraduate students in the United States. According to The College Board (2018), students spend an average of $1,240 on books and supplies each year. Expensive textbook and course material costs negatively impact college students because students cannot learn from course materials that they cannot afford to buy. In 2018, the Florida Office of Distance Learning surveyed over 21,000 students at public universities in the state of Florida, revealing that students are responding to the high cost of textbooks by “not purchasing the required textbook (64.2%); taking fewer courses (42.8%); not registering for a specific course (40.5%); earning a poor grade (35.6%); and dropping a course (22.9%)” (Florida Virtual Campus, p. 13).

Selection of appropriate course materials is one of the most important ways faculty can contribute to the success of students in their courses. An increasing number of faculty are concerned about the high cost of textbooks and the financial burden imposed on their students. In a survey of 2,000 faculty members in 2018, Inside Higher Ed reported that “83% of faculty members agree, including 58% who strongly agree, that textbooks and course materials cost too much” (Jaschik & Lederman, p. 47) and 70% favor freely-available, open educational resources (i.e., teaching and learning materials that are openly licensed, giving users the legal permission to retain, reuse, revise, remix, and redistribute the material) as a solution to the textbook affordability crisis. Despite faculty members’ awareness about the impact that textbook costs have on student success, changing course materials takes a lot of time and effort, and faculty “often feel that they have been left on their own to find solutions” (Waller et al., 2019, p. 587).

In recent years, academic libraries across North America have responded to the textbook affordability movement in higher education. Many libraries have launched initiatives to encourage faculty to consider using alternative course materials such as library-licensed resources and/or Open Educational Resources (OER) to reduce the cost for students. Open Educational Resources are teaching and learning materials that reflect the following open values and practices (Cape Town Open Education Declaration, 2008; Hewlett, 2013; Wiley, 2014):

- Freedom to reuse: enabling open sharing of resources

- Free cost: offering free and open exchange of information

- Equitable access: providing universal access to knowledge

The content of OER provides accessible, affordable, and equitable access to shared knowledge.

Academic libraries, historically, have focused on providing access to knowledge and sharing knowledge, but library support for textbook affordability initiatives is not sufficient by itself. A successful way for libraries to serve the needs of both students and faculty is to build partnerships with other campus units on open educational initiatives, while demonstrating its value and improving visibility to stakeholders across campus. (Cummings-Sauls et al., 2018).

For students, the practical benefits of OER go beyond cost savings. Many students favor OER for: (a) providing them with immediate access to course reading materials, (b) the ability to access course materials from multiple devices, (c) replacing the need to carry heavy books to class, and (d) not being required to buy textbooks that they sell back at the end of the semester for a fraction of the price paid. Vojtech and Grissett (2017) studied the perceptions of students enrolled in psychology courses taught by faculty who use OER and found that, in general, students perceive faculty as more creative and kind when the faculty use OER and were more likely to take a class using an open textbook. Open textbooks, like all OER materials, have been published and licensed to be freely used, adapted, and distributed. Many open textbooks have been peer-reviewed by faculty to assess their quality. They can be downloaded for no cost, or printed at a low cost.

Phase One: Raising Awareness of Affordable Course Materials at The George Washington University

The George Washington University, a private, research university located in Washington, DC with a total student population of over 27,000 undergraduate/graduate students, is one of the most expensive universities to attend in the United States. Students from all around the world come to study at GWU. Despite all of this prestige, many GWU undergraduate students struggle to afford the cost of course materials and are faced with choosing between buying a required $250 textbook and groceries for the month.

Recognizing the financial pressures faced by students due to the rising cost of textbooks in higher education, in 2016, a small group of GWU librarians with a passion for advocating for affordable course materials self-organized and formed an Open Educational Resources (OER) Team at GW Libraries. The size of the OER Team varied (between three and five members) over the years, but a key to success has been recruiting library staff members who bring a diverse skill set (e.g. including instructional design, project management, course reserves, outreach/communications, and mid-level management) to the team. Team members spend a significant amount of time developing grassroots advocacy across appropriate constituencies of the university, educating faculty about alternatives to expensive textbooks, and researching appropriate open educational resources. This is in addition to their required duties, which makes it essential to have the support of one’s direct library supervisor.

The motivation for GW Libraries’ OER Team was based on the institution’s strategic focus on improving the student experience. One way that the OER Team impacted student success was by encouraging faculty to replace expensive course materials with an option more equitable, affordable, and accessible—an open textbook. Open Educational Resources have gained traction in higher education as a cost-saving alternative to traditional commercial course textbooks and the OER Team’s working strategy was to “save the most students the most amount of money on course materials.” Numerous conversations with campus stakeholders helped to identify faculty teaching high enrollment, undergraduate courses with multiple sections, especially those using expensive required textbooks. The team held OER Workshops on campus, gave presentations at faculty events, and delivered email campaigns. In Spring 2017, email messages (see Appendix A) were sent to six faculty in the psychology department who were listed in the GWU Schedule of Classes as teaching PSYC 1001, an introductory-level, general psychology course. The OER Team received one response—from Dr. Dennis Schell, Assistant Professor of Psychology at GWU, who expressed his concern about the escalating price of general psychology textbooks and his interest in looking for an alternative option for the introductory-level, general psychology course that he taught each semester.

Additionally, he wanted to add engaging digital learning resources to augment course lectures. Members of GW Libraries’ OER Team met with Dr. Schell to investigate the feasibility of transitioning from an expensive, traditional, general psychology textbook to an open textbook. The OER Team presented information hosted on their LibGuide, Open Textbooks and Resources for Faculty, to Dr. Schell, highlighting the unique benefits of open course materials for students and faculty—affordable and equitable access to course readings, convenience of digital access, ability to revise/remix content by tailoring it to specific teaching style and course objectives, and allowing for the sharing of learning content in multi-modal formats (see Appendix B). At a second meeting, Dr. Schell shared his course syllabus with the OER Team and discussed the current textbook’s level of use and what was essential in a replacement. Over the next few weeks, librarians used their expert searching skills to locate peer-reviewed, general psychology open textbooks. The librarians spent many hours combing through curated OER collections (such as the Open Textbook Library and OER Commons) as well as lists of openly licensed college textbooks publishers (such as OpenStax) to find content best suited for an undergraduate general psychology course. Three peer-reviewed psychology open textbooks from the Open Textbook Library were initially selected and information on these sources was shared with Dr. Schell via email. As the subject-matter expert, Dr. Schell completed his review process over the course of several months in four strategic phases: (a) understanding students’ perceptions and uses of a textbook, (b) reviewing the affordable options, (c) adoption of the open textbook and evaluation of its use, and (d) implementation and evaluation of student satisfaction.

Phase Two: Understanding Students’ Perceptions and Uses of a Textbook in General Psychology

In order to contextualize the benefits of using an open textbook in his general psychology classes, Dr. Schell gathered feedback from students enrolled in his general psychology course over the span of several semesters (Spring 2017, Fall 2017, Spring 2018, Fall 2018, and Spring 2019) by conducting a brief four-question survey about textbook preferences in each of his four separate general psychology classes. These surveys, as well as the subsequent nine-question surveys (see Phase 5), were conducted anonymously with no identifiable data; and students were given 1% credit toward their grade (IRB#NCR202208, exempt). The four-question survey concentrated on textbook cost, students’ preferred format of materials (print vs. digital), and students’ perceptions of using an open textbook in the course. The questions were:

- “The price of a textbook is important to me.”

- “I prefer my textbook to be: hard bound, soft bound, online.”

- “I would like having a textbook in general psychology online for free.”

There was also a section for open comments. Approximately two-thirds of the students in each class were female, and the classes were highly diverse in terms of race, ethnicity, and country of origin. Most students were first year students ranging from 17 to 22 years of age. The participation rate of the surveys ranged from 82.4% to 98.96% (see Table 1).

Table 1

Participation Rate for Students Enrolled in General Psychology

|

Semester |

Total Students Enrolled |

Number and Percentage of Students Responding to Survey |

|---|---|---|

|

Spring 2017 |

94 |

86 (91.48%) |

|

Fall 2017a (Section 13) |

97 |

80 (82.47% |

|

Fall 2017b (Section 15) |

97 |

84 (86.59%) |

|

Spring 2018 |

96 |

94 (97.91%) |

|

Fall 2018a (Section 13) |

91 |

85 (93.40%) |

|

Fall 2018b (Section 15) |

97 |

96 (98.96%) |

|

Spring 2019 |

97 |

88 (90.72%) |

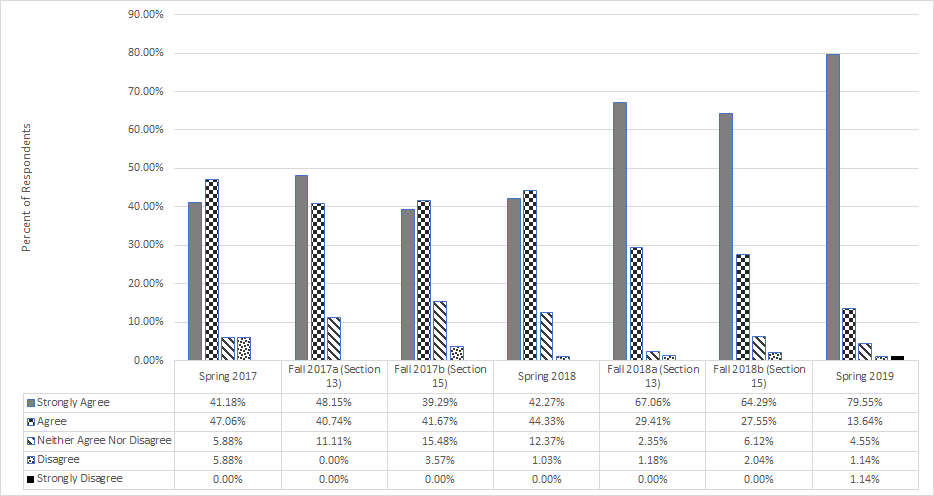

The first question, “The price of a textbook is important to me,” was given to students in all seven semesters (see Figure 1). Students overwhelmingly indicated the price of a textbook was important, which is consistent with recent research (Waller et al., 2018).

Figure 1

General Psychology Surveys: Both Pre- and Post-Adoption (Seven Semesters) Question 1: The Price of a Textbook is Important to Me.

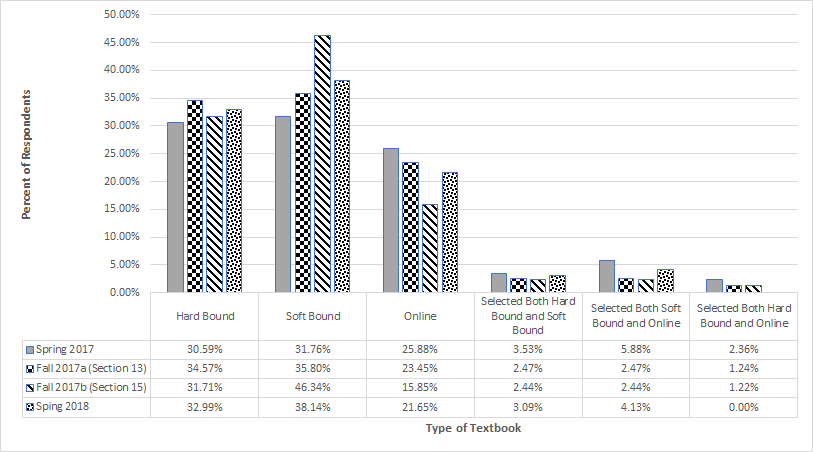

The second question, “I prefer my textbook to be hard bound, soft bound, or online,” revealed that roughly two-thirds to three-fourths of students preferred a print copy (either hard bound or soft bound) over an online copy of a textbook (see Figure 2). This result aligns with similar findings in national studies that indicated a majority of students preferred print over an electronic format (Jhangiani et al., 2018; Millar & Schrier, 2015; Woody et al., 2010; Shepperd et al., 2008).

Figure 2

General Psychology Surveys: Pre-Adoption (Four Semesters) Question 2: I Prefer My Textbook To Be:

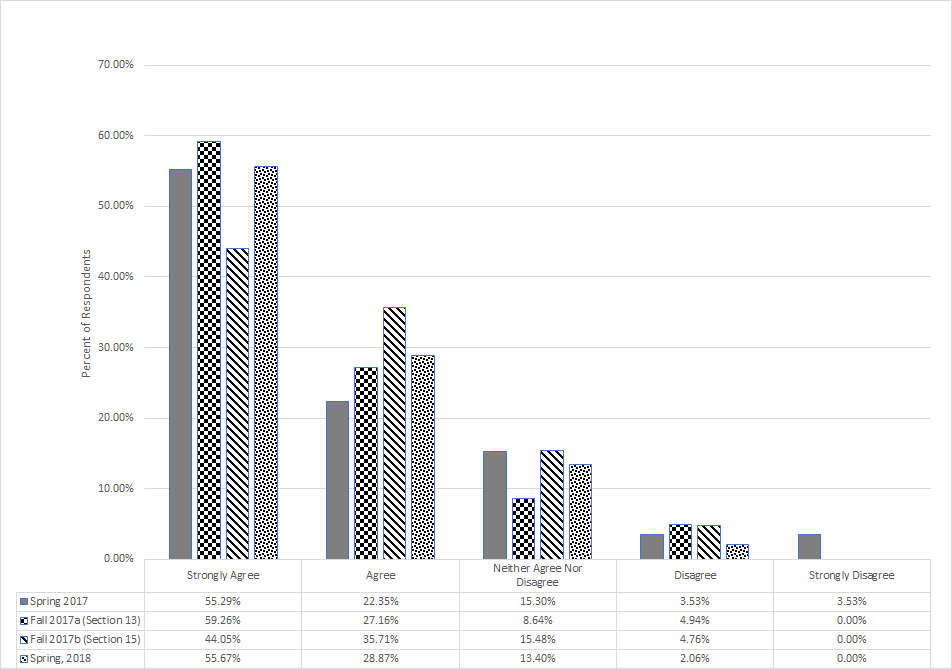

The third question, “I would like to have a textbook in general psychology online for free,” revealed that students overwhelmingly would prefer a free online book (see Figure 3), in spite of the fact that they tended to prefer print copies (see Figure 2). In the open comments section, however, students were quick to point out that they should have a choice between a print copy and an online copy.

Figure 3

General Psychology Surveys: Pre-Adoption (Four Semesters)

Question 3: I Would Like to Have a Textbook in General Psychology Online for Free.

Phase Three: Reviewing the Affordable Options in General Psychology

Based on the findings above, Dr. Schell reviewed three psychology open textbooks suggested by the OER Team. Only one, OpenStax (Rice University), offered both a free online version and a print version (hard bound and soft bound) for purchase at a reasonable price ($50 or less). The OpenStax psychology textbook is peer-reviewed, customizable, and openly licensed under a Creative Commons License 4.0 International (OpenStax, 2017; Watson et al., 2017).

The textbook content also had to meet the standards of the American Psychological Association (APA). According to the February 2011 Report, Principles for Quality Undergraduate Education in Psychology:

The introductory course and the psychology major provide a broad foundational understanding of the field from the perspective of content areas spanning levels of organization from cellular to ecological. Regardless of the structure of an individual department’s curriculum, the major should incorporate multiple core perspectives on psychology. Because the introductory course is the only formal exposure to psychology that most educated citizens will have, this course should reflect the nature of psychology as a scientific discipline and include sections from different basic domains. Integration across perspectives should be incorporated into the introductory course by, for example, organizing the course topically or providing an in-depth topical “case study” of integration. Many of the controversies in psychology result from different perspectives on human thought and behavior, so in teaching about controversies (e.g., nature/nurture issues), faculty should expose students to theoretically diverse perspectives. Departments should consider carefully the depth and breadth of topics to cover in their classes. Content coverage has become a critical factor in the psychology curriculum as a result of the explosion of research findings and the plethora of important topics that could be included in any course. (p. 13)

Dr. Schell hired a student, a junior psychology major, to review the contents of the OpenStax textbook. The student made a comprehensive list of topics typically covered in a standard general psychology course. The subsequent list of 249 topics was determined to be identical or similar to the major topics covered in most traditional, general psychology textbooks, and met the APA guidelines.

The next step involved hiring a second student, the third author of this chapter, who had been in Dr. Schell’s general psychology class, which at the time, used a traditional textbook. She made a more in-depth analysis of the OpenStax book in a one-page document focusing on: (a) a comparison of the OpenStax book to the current traditional textbook used in Dr. Schell’s classes, and (b) a comparison of the OpenStax print and online versions. She used the following criteria for her analysis: (a) the quality of language, (b) organization, (c) content, and (d) educational aids. Both the print and online versions were largely consistent in layout, thus allowing students to switch easily between versions. The presentation of the material (e.g., formatting, etc.) was the same and equally conducive to learning in each version. She also reported that the explanation and treatment of various psychological concepts, organization of chapters, graphics, etc. were on par with that given by other textbooks. Based on the student surveys and the two students’ analyses, Dr. Schell decided to adopt the OpenStax open textbook on a provisional basis.

Phase Four: Adoption of OpenStax General Psychology Textbook

Dr. Schell selected the OpenStax open textbook, Psychology, as the best open resource to support the learning needs of students taking his general psychology course. Consequently, the chair of the OER Team, librarian Dorinne Banks, and Dr. Schell formed a collaborative partnership to transition from the previously used traditional, general psychology textbook, costing $250 (new), to the freely-available OpenStax psychology open textbook. For the more than 300 students who Dr. Schell teaches each year, that’s a substantial savings per student. During the initial meetings and in follow-up emails, the conversations between Banks and Dr. Schell focused on what types of new material to integrate and specific topics/learning objectives that these materials needed to align with. For example, Dr. Schell knew that he wanted to include more digital content as a supplemental resource, so one student hiree and Banks provided links to freely-available educational videos online and library subscription content (see Appendix C). Redesigning a course’s curriculum around a new open textbook and revising the course’s syllabus is a time-consuming process (see Appendix D). Additionally, developing open course readings is just one part of the new design. The redesign process also influences class lecture content (e.g. PowerPoint presentations), learning assessments, homework assignments, etc. As a result, Dr. Schell was able to use the OpenStax psychology textbook to better match his learning goals (see Appendix E) for the students in his introductory-level general psychology course. The importance of a collaborative partnership between faculty and librarians was essential in this process.

Phase Five: Implementation and Evaluation of Student Satisfaction of the OpenStax General Psychology Textbook

Dr. Schell used the OpenStax textbook in all sections of the general psychology courses he taught—two sections in fall 2018 and one section in spring 2019. Implementation of a short, nine-question student survey was conducted in each class to determine students’ satisfaction with the open textbook. The questions were:

- “I am using the following textbook: on-line free, hard-bound purchased, soft-bound purchased.”

- “The price of a textbook is important to me.”

- “The OpenStax textbook was easy to use.”

- “How would you rate the readability of the OpenStax textbook?”

- “How would you rate the quality of the OpenStax textbook compared to other traditional textbooks you have used?”

- “Would you recommend Dr. Schell continue using the OpenStax textbook?”

- “What is the best thing about the OpenStax textbook?”

- “What is the least favorite thing about the OpenStax textbook?”

- “Is there anything else you would like to say about the OpenStax textbook?”

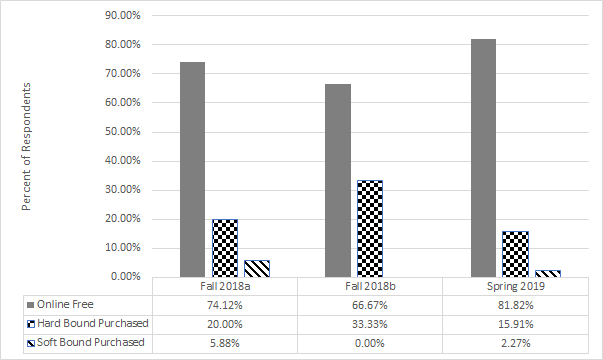

The first question asked, “I am using the following textbook:” The results showed that between 66.67% and 81.82% of respondents were using the online free OpenStax textbook, between 15.91% and 20% were using the hard bound printed version, and up to 5.88% were using the soft bound printed version (see Figure 4). It is to be noted that in the four surveys before adoption of the open textbook, students overwhelmingly indicated that they preferred print versions (hard or soft bound). Interestingly, post-adoption, most students used the online, free textbook version. It should also be noted that some students, for a variety of reasons (e.g., easier to read, easier to highlight/annotate), still wanted a print version, which is consistent with the comments students made in the four surveys prior to adoption.

Figure 4

General Psychology Surveys: Post-Adoption (Three Semesters) Question 1: I Am Using the Following Textbook:

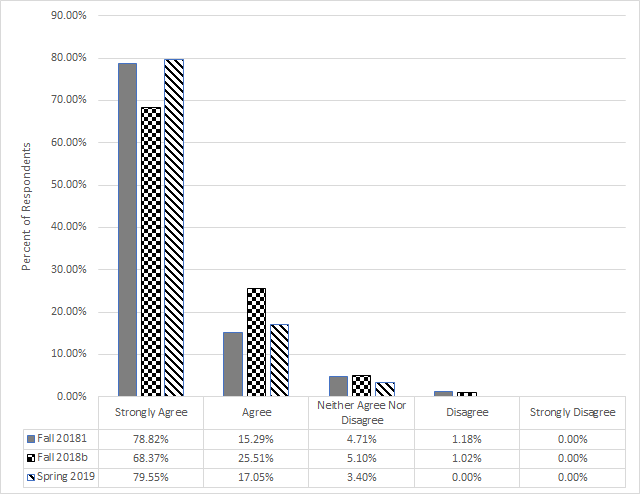

The second question asked, “The price of a textbook is important to me.” Students overwhelmingly stated that the price of a textbook was important to them, which is consistent with the results of the four surveys (see Figure 1) conducted before Dr. Schell adopted the open textbook. When students were asked if “the OpenStax textbook was easy to use,” (the third question) between 68.37% and 79.55% indicated they “strongly agree,” and between 17.05% and 25.51% indicated they “agree.” Clearly, students found the OpenStax open textbook easy to use (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

General Psychology Surveys: Post-Adoption (Three Semesters) Question 3: The OpenStax Textbook Was Easy to Use.

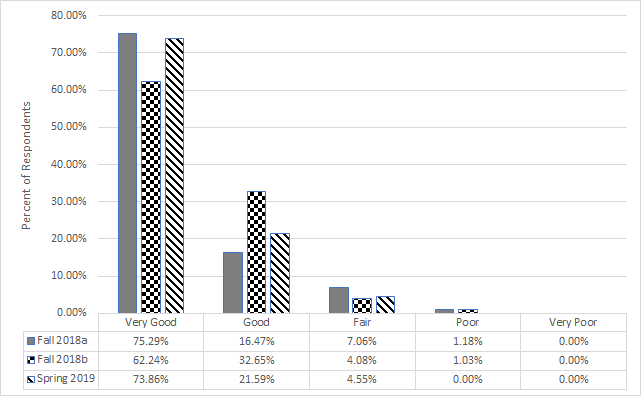

When students were asked about the readability (i.e., “How would you rate the readability of the OpenStax textbook?”), between 62.24% and 75.29% indicated that readability was “very good,” and between 16.47% and 32.65% indicated it was “good.” A majority of students overwhelmingly thought the readability was good or very good (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

General Psychology Surveys: Post-Adoption (Three Semesters) Question 4: How Would You Rate the Readability of the OpenStax Textbook?

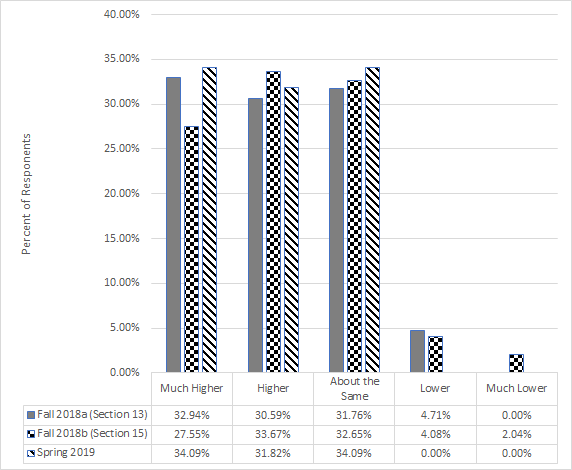

When students were asked to compare (see Figure 7) the overall quality (i.e., “How would you rate the quality of the OpenStax textbook compared to other traditional textbooks you have used?”), between 27.55% and 34.09% rated the OpenStax textbook “much higher,” between 30.59% and 33.67% rated it “higher,” and between 31.76% and 34.09% of respondents rated it “about the same.” There were two trends observed. First, the majority of students rated the OpenStax textbook higher or much higher, which suggests the quality of the OpenStax textbook, in their opinion, exceeded that of most traditional textbooks. Second, about one-third of students rated the OpenStax textbook “about the same” as a traditional textbook and very few rated it as “lower” or “much lower,” which suggests that students viewed the quality of the open textbook as matching or exceeding that of other traditional textbooks.

Figure 7

General Psychology Surveys: Post-Adoption (Three Semesters) Question 5: How Would You Rate the Quality of the OpenStax Textbook Compared to Other Traditional Textbooks You Have Used?

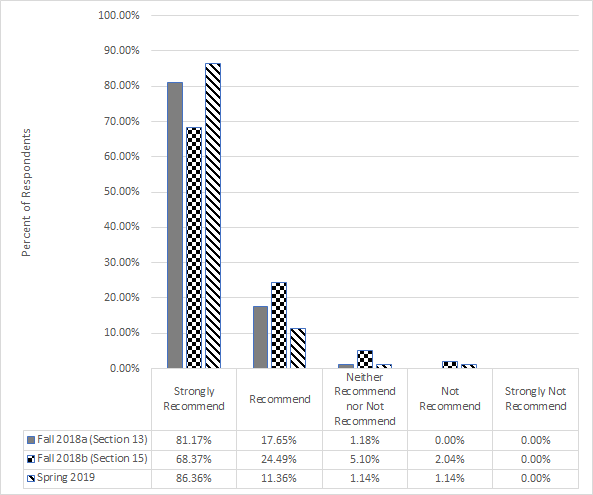

Students overwhelmingly recommended (i.e., “Would you recommend Dr. Schell continue using the OpenStax textbook?”) that Dr. Schell continue to use the OpenStax textbook (see Figure 8). To summarize survey questions 4, 5, and 6, responses indicated that students were highly satisfied with the OpenStax textbook.

Figure 8

General Psychology Surveys: Post-Adoption (Three Semesters) Question 6: Would You Recommend Dr. Schell Continue Using the OpenStax Textbook?

The last three questions in the survey were open-ended. The first question asked, “What is the best thing about the OpenStax textbook?” Out of 272 surveys completed, there were a total of 212 responses to this question (see Table 2). The most frequent comment was the fact that the online version of the book was free (67 comments), followed in descending order by: (a) how easily students could access the book, (b) how easy it was to use, (c) how easy it was to read, and (d) the review/practice questions at the end of each chapter. Additional interesting comments included: (a) “I like that I can download it and then use the search feature on my computer to find certain terms,” (b) “I don’t have to carry a heavy textbook,” (c) “being able to put it side by side next to notes or Quizlet,” (d) “The book won’t get ruined,” and (e) “Over break I didn’t need to lug a book to study, and I was able to do my notes whenever, wherever.” These GWU student comments mirror the findings from Grissett and Huffman’s (2019) study of psychology open textbooks in which students identified cost, weight, and convenience as the biggest advantages of open textbooks.

Table 2

Most Frequently Occurring Responses to the Question: “What is the Best Thing About the OpenStax Textbook?

|

Parameters |

Fall 2018a Section 13 |

Fall 2018b Section 15 |

Spring 2019 |

Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of Respondents |

60 |

76 |

76 |

212 |

|

Cost/Price (Free) |

24 |

25 |

18 |

67 |

|

Ease of Access |

8 |

14 |

12 |

34 |

|

Ease of Use |

10 |

9 |

15 |

34 |

|

Easy to Read |

6 |

12 |

13 |

31 |

|

Practice Questions |

3 |

9 |

5 |

17 |

The second open-ended question asked, “What is the least favorite thing about the OpenStax textbook?” Out of the 272 surveys completed, there were 179 responses (see Table 3). The most frequent comment was “none,” “n/a,” or similar suggesting that the student had no least favorite comment to make. There were 27 comments reflecting online issues such as: (a) “inaccessible without internet connection,” (b) “scrolling between chapters,” (c) “sometimes slow to load.” There were 25 comments reflecting content issues such as: (a) “some sections seem oversimplified or not relevant,” (b) “certain aspects could have been further explained,” (c) “maybe sometimes it can be too repetitive.” There were 15 comments noting that the chapters were too long and 13 comments that the authors provided only answers to the odd numbered practice questions. Finally, there were eight comments reflecting preference for print versions such as (a) “I just prefer having it on paper rather then my computer screen,” (b) “sometimes I wish I had the physical book because I don’t like reading on a computer,” and (c) “a book is so easy to focus on rather than a screen, which makes it a little more difficult.”

When transitioning from a traditional print textbook to an online version, it is crucial to obtain both positive and negative feedback. The negative feedback obtained here was particularly valuable because it allows Dr. Schell and the team to address the issues that may interfere with students’ learning. For example, feedback confirmed that students need a choice between an online version and a print copy. The survey also provided important feedback about the practice questions, which can easily be remedied in future semesters by providing all the correct answers. The positive feedback was equally important. In this case, the feedback reinforced how well students liked the OpenStax open textbook and the decision to continue its use in future classes.

Table 3

Most Frequently Occurring Responses to the Question: “What is the Least Favorite Thing About the OpenStax Textbook?

|

Parameters |

Fall 2018a Section 13 |

Fall 2018b Section 15 |

Spring 2019 |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

None/Not Apply |

11 |

16 |

15 |

42 |

|

Online Issues |

10 |

7 |

10 |

27 |

|

Content |

4 |

11 |

10 |

25 |

|

Chapter Length Too Long |

2 |

9 |

4 |

15 |

|

Practice Questions |

3 |

2 |

8 |

13 |

|

Preference for Printed Copy |

3 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

The last open-ended question asked, “Is there anything else you would like to say about the OpenStax textbook?” Out of the 272 surveys, there were 88 responses (see Table 4). The responses were overwhelmingly positive with 22 comments suggesting Dr. Schell continue to use the OpenStax textbook. Examples of positive comments include: (a) “I believe the idea behind the free online textbook is something that should be accessible for more courses,” (b) “This is the second class I’ve used OpenStax and I still think it’s great!”, (c) “Great pick!” Examples of negative comments included: (a) “Knowing if there is a cheaper version beforehand would be nice,” (b) “if there is a video for explanation, probably it is going to be more helpful and interesting,” (c) “Better to have answers for even number problems.”

Table 4

Summary of Type of Responses to the Question: “Is There Anything Else You Would Like to Say About the OpenStax Textbook?”

|

Parameters |

Fall 2018a Section 13 |

Fall 2018b Section 15 |

Spring 2019 |

Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of Respondents |

24 |

29 |

35 |

88 |

|

Positive Comments |

10 |

12 |

15 |

58 |

|

Negative Comments |

2 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

|

Continue to Use/ Recommend |

5 |

6 |

11 |

22 |

|

No or None |

7 |

9 |

8 |

24 |

One concern Dr. Schell had was whether students’ learning (e.g., final course grades) suffered as a result of transitioning to the OpenStax textbook. The grades for all seven semesters were calculated based on the following formula (see Table 5).

Table 5

Letter Grade and Point Equivalent

| Letter Grade | Point Equivalent |

|---|---|

| A | 4.0 |

| A- | 3.7 |

| B+ | 3.3 |

| B | 3.0 |

| B- | 2.7 |

| C+ | 2.3 |

| C | 2.0 |

| C- | 1.7 |

| D+ | 1.3 |

| D | 1.0 |

| D- | 0.7 |

| F | 0 |

An independent samples t-test was conducted to compare the grades of students using a traditional textbook and students using the OpenStax open textbook. There was a significant difference in the grades for students in the class using a traditional textbook (M = 2.96, SD = .814) in comparison to students using OpenStax (M = 3.20, SD = .713); t(663) = -3.986, p= .000. Students in the four semesters before Dr. Schell adopted OpenStax had an average letter grade in the C+ and B- range. Students in the three semesters after adoption had an average letter grade in the B- range. We cannot state that the OpenStax textbook was responsible for the increase in grade, but we can state that the use of the OpenStax textbook did not hurt student learning as assessed by grades. This aligns with research results from a large-scale study (Colvard et al., 2018) at the University of Georgia which showed that:

OER adoption does much more than simply save students money and address student debt concerns. OER improve end-of-course grades and decrease DFW (D, F, and Withdrawal letter grades) rates for all students. They also improve course grades at greater rates and decrease DFW rates at greater rates for Pell recipient students, part-time students, and populations historically underserved by higher education (p. 262).

Conclusion

Transitioning to an online general psychology textbook that was peer-reviewed, affordable, customizable, accessible, and meets the standards of the American Psychological Association was no easy task. A thoughtful and rigorous process was needed in order to design a quality learning experience for students and this detailed process was time-consuming (see Appendix D). We learned a number of things as a result that may serve as a template for other faculty and librarians. Faculty interested in redesigning their courses by replacing a traditional course textbook with open course materials do not need to tackle this effort alone. A team effort is essential. The insights of a librarian who is knowledgeable about open educational resources as well as skilled in locating open materials and understanding open licensing will make the project easier.

A second important essential element is employing student feedback from the beginning. For example, we learned through student surveys that they preferred a print textbook (hard or soft bound), but strongly supported a free online textbook, provided they had a choice of a print or digital version. Additionally, two student assistants who helped the faculty member evaluate the textbook, in detail, provided significant information about how well the textbook aligned with the American Psychological Association standards and how well it aligned with traditional, general psychology textbooks.

Third, after we adopted the OpenStax textbook, we learned through student surveys that they overwhelmingly liked having a free, online textbook and strongly recommended that Dr. Schell continue to use it. Also, students’ grades did not suffer as a result of using the OpenStax textbook. This made the decision to continue using the open textbook easier.

GW Libraries’ OER Team members currently continue their campus advocacy plan for affordable and open course materials based on the strategy that was successful when partnering with Dr. Schell: (a) purposefully aligning OER advocacy with the institution’s strategic plan; (b) prioritizing advocacy to courses based on the strategy to “save the most students the most amount of money on course materials,” (c) targeting faculty teaching high enrollment, undergraduate courses with multiple sections, especially those using expensive required textbooks; and, (d) having 1:1 conversations with faculty members while sharing examples of OER course materials in their subject area. Team members report that 1:1 conversations are the most successful format of outreach. These conversations conclude with team members asking faculty, “Are you interested in using open course materials?” Finkbeiner (2019) discussed this concept during her presentation: “Effectively encouraging OERs on your campus” (slide 9) in which she referred to it as a “direct tactic”—that is, a strategy that results in getting a direct faculty response of yes, no, or maybe—tell me more.

The team’s less successful strategies included stand-alone OER campus workshops and email campaigns. For example, in the original email campaign to GWU faculty teaching a general psychology course, only one of six faculty responded to the OER Team’s email. In fact, Nicole Finkbeiner (2019) stated in her webinar, “Effectively encouraging OERs on your campus” that only 23% of emails are opened by faculty. Since that approach was not effective, the OER Team adopted a new approach by directing personalized emails to academic department chairs in order to gain higher level buy-in before communicating with course level teaching faculty. We also learned the importance of clearly communicating the expectations of roles at the outset of a collaborative project. Time constraints will vary in amount depending on the librarian’s availability at various times throughout the school year. In each project to switch to affordable course materials, Banks meets with the faculty member and discusses that her role in evaluating the suitability of OER content for a course is based on two factors: affordability and relevance. It is the faculty member’s role to evaluate the quality, fit, and appropriateness of OER content. By using a thorough process that is well grounded in research and contributes to a quality learning experience for students, a collaborative team of faculty, librarians, and students provides the expertise necessary for selecting and adopting an appropriate open textbook.

References

American Psychological Association, Report (February 2011). Principles for Quality Undergraduate Education in Psychology. https://www.apa.org/education/undergrad/principles

Cape Town Open Education Declaration. (2008). https://www.capetowndeclaration.org/

College Board. Average estimated undergraduate budgets, 2018-19. Trends in Higher Education Series: Trends in College Pricing. https://trends.collegeboard.org/college-pricing/figures-tables/average-estimated-undergraduate-budgets-2018-19#globalheader

Colvard, N. B., Watson, C. E., & Park, H. (2018). The impact of open educational resources on various student success metrics. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 30(2), 262-276. http://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/pdf/IJTLHE3386.pdf

Cummings-Sauls, R., Ruen, M., Beaubien, S., & Smith, J. (2018). Open partnerships: Identifying and recruiting allies for open educational resources initiatives. OER: A field guide for academic librarians. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/librarian_pubs/72

Finkbeiner, N. (2019, October 8). Effectively encouraging OERs on your campus [webinar]. In Association of Southeastern Research Libraries Archive of Webinars & Materials. http://www.aserl.org/archive/

Finkbeiner, N. (2019). Effectively encouraging OERs on your campus [PowerPoint slides]. https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1cBmo3jNRYSQRfulJhibKu3UlSeEMwKNwS2Wy2JCKjYU/edit?usp=sharing

Florida Virtual Campus. (2019). 2018 student textbook and course materials survey. Tallahassee, FL: Florida Virtual Campus, Office of Distance Learning & Student Services. https://dlss.flvc.org/documents/210036/1314923/2018+Student+Textbook+and+Course+Materials+Survey+Report+–+FINAL+VERSION+–+20190308.pdf/

Grissett, J., & Huffman, C. (2019). An open versus traditional psychology textbook: Student performance, perceptions, and use. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 18(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725718810181

Hewlett (2013). Open educational resources. https://hewlett.org/strategy/open-educational-resources/#overview

Jaschik, S., & Lederman, D. (2018). Faculty attitudes on technology. Inside Higher Education. https://mediasite.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/2018-Faculty-Survey-Mediasite.pdf

Jhangiani, R. S., Dastur, F. N., Le Grand, R., & Penner, K. (2018). As good or better than commercial textbooks: Students’ perceptions and outcomes from using open digital and open print textbooks. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2018.1.5

Millar, M., & Schrier, T. (2015). Digital or printed textbooks: Which do students prefer and why? Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 15(2): 166-185. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313220.2015.1026474

OpenStax. (2017). About our textbooks. https://openstax.org/subjects

Seaman, J. E., & Seaman, J. (2018). Freeing the textbook: Educational resources in US higher education. Oakland, CA: Babson Survey Research Group. https://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/freeingthetextbook2018.pdf

Shepperd, J. A., Grace, J. L., & Koch, E. J. (2008) Evaluating the electronic textbook: Is it time to dispense with the paper text? Teaching of Psychology, 35(1): 2-5. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1016.931&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Spielman, R. (2017). Psychology (OpenStax). Houston: Rice University. http://cnx.org/content/col11629/latest/.

Vojtech, G., & Grissett, J. (2017). Student perceptions of college faculty who use OER. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(4): 155-171. http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/download/3032/4205

Waller, M., Cross, W., & Hayes, E. (2019). The open textbook toolkit: Developing a new narrative for OER support. Paper presented at the Association of College & Research Libraries 2019 Conference. http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2019/TheOpenTextbookToolkit.pdf

Watson, C., Domizi, D., & Clouser, S. (2017). Student and faculty perceptions of OpenStax in high enrollment courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5). http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/2462/4299

Wiley, D. (2007, 2014). 5R permissions. http://opencontent.org/definition/

Woody, W. D., Daniel, D. B., & Baker, C. A. (2010). E-books or textbooks: Students prefer textbooks. Computers & Education, 55(3): 945-948. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.04.005

Contact Information

Author Dennis E. Schell may be contacted at dschell@gwu.edu. Author Dorinne E. Banks may be contacted at dbanks@gwu.edu.

Feedback, suggestions, or conversation about this chapter may be shared via our Rebus Community Discussion Page.

APPENDIX A

Draft Email to Psychology Faculty who Teach Large, Introductory Psychology Courses

Dear ________,

An important initiative promoted by Provost Maltzman and the Student Association Senate is underway at GW to encourage and support the adoption of open and affordable educational resources (OERs) in courses here. OERs are online course materials, such as open textbooks, that are available at no cost and are generally openly licensed such that faculty can freely use, remix, and adapt them. OERs are being used in courses at universities throughout the world, and there are many quality OERs available in a variety of subjects, including psychology.

I am writing to you as a member of the psychology faculty who teaches General Psychology to encourage you to consider adopting an open psychology textbook in lieu of a commercially published textbook the next time you teach this course. [If textbook known: Your current textbook [Insert Title] costs [Insert Cost]. If textbook unknown: Many traditional introductory psychology textbooks cost $100-$200.] This is a significant financial burden for our students, particularly for the many students receiving financial aid to attend GW. With the large number of students who enroll in General Psychology, transitioning to an open textbook in this course could result in thousands of dollars in savings for our students.

In addition to saving students money, OERs have a number of other benefits as well. Use of OERs can actually improve student learning and performance. This study, for example, found that in “three key measures of student success—course completion, final grade of C- or higher, course grade–students whose faculty chose OERs generally performed as well or better than students whose faculty assigned commercial textbooks.” The authors suggest that these outcomes are a result of increased access in that all students in courses using open textbooks have free, online access compared to students in courses using commercial textbooks where some of them may not purchase the textbook due to cost. This is not surprising in light of surveys showing that many college students have chosen not to purchase a textbook due to its cost, even if they thought this would hurt their grade in the class.

If you are interested in adopting an open textbook in General Psychology or your other courses, please don’t hesitate to contact me or any member of our Open Educational Resources Team at open@gwu.edu. We can help identify suitable open textbooks or other OERs for your courses and answer any questions you have about these resources. Please feel free to forward this message to any of your colleagues who may be interested as well.

Sincerely,

APPENDIX B

Information Sheet Given to Faculty

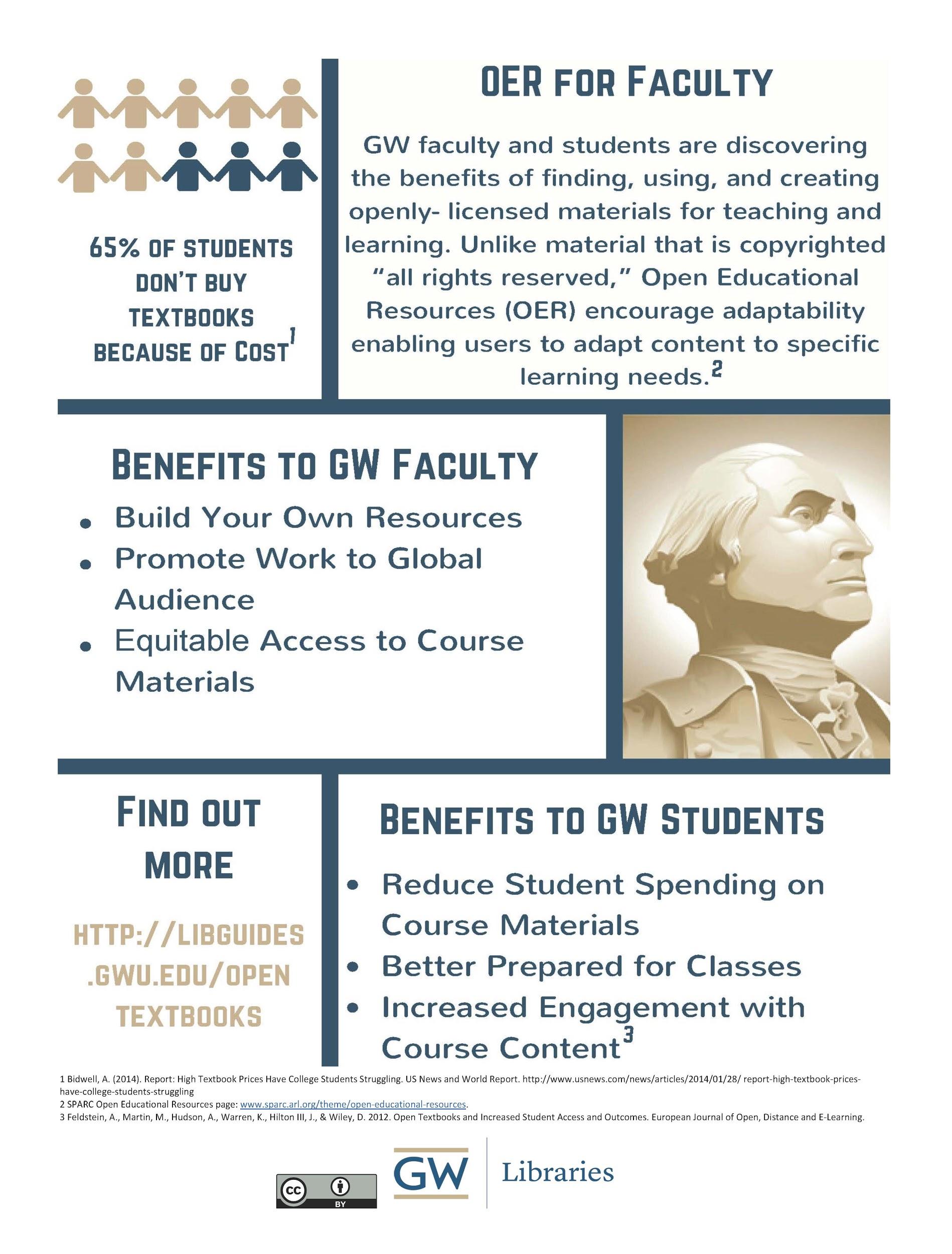

Full Text of Information Sheet: OER for Faculty

65% of students don’t buy textbooks because of cost[1]

GW faculty and students are discovering the benefits of finding, using, and creating openly-licensed materials for teaching and learning. Unlike material that is copyrighted “all rights reserved,” Open Educational Resources (OER) encourage adaptability enabling users to adapt content to specific learning needs.[2]

Benefits to GW faculty:

- build your own resources

- promote work to global audience

- equitable access to course materials

Benefits to GW students:

- reduce student spending on course materials

- better prepared for classes

- increased engagement with course content[3]

Find out more: http://libguides.gwu.edu/opentextbooks

GW Libraries, CC-BY

APPENDIX C

Free On-Line Resources For General Psychology

Chapter 1: Introduction to Psychology

- Crash Course Psychology #1 (YouTube Video)

- Important Historical Figures in Psychology (Web Image)

- Perspectives in Psychology (Web Image)

- Psychoanalytic Theory, Freud (YouTube Video)

- Gestalt Psychology (YouTube Video)

- Behaviorism (YouTube Video)

- Humanism: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (YouTube Video)

- Social Psychology (YouTube Video List)

Chapter 2: Psychological Research

- Crash Course Psychology #2 (Psychological Research) (YouTube Video)

- Correlational Research (Ch. 2 lecture YouTube Video)

- Types of Psychological Research (Web Image)

- Psychological Research Comparisons (Web Image)

Chapter 3: Biopsychology

- Ch.3 Lecture (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Biology #10 (DNA Structure & Replication) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Biology #9 (Heredity) (YouTube Video)

- The Human Genome/Your DNA (YouTube Video)

- What is a gene? (YouTube Video)

- What is DNA and how does it work? (YouTube Video)

- How Human Genome is Sequenced (YouTube Video)

- Khan Academy: Twin and Adoption Studies (YouTube Video)

- Chromosomes under a microscope (Web Image)

- Crash Course Psychology #3 (The Chemical Mind) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #4 (The Brain Overview) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Anatomy & Physiology #8 (Nervous System Part 1) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Biology #26 (The Nervous System) (YouTube Video)

- Khan Academy (Cerebral Cortex Overview) (YouTube Video)

- Khan Academy (More detail on Cerebral Cortex Structure and Function) (YouTube Video)

- Khan Academy (Anatomy of a Neuron) (YouTube Video)

- 2-Minute Neuroscience: The Neuron (YouTube Video)

- 2-Minute Neuroscience: Neuroimaging (YouTube Video)

- 2-Minute Neuroscience: Synaptic Transmission (YouTube Video)

- A Rod Through His Brain: The Story of Phineas Gage (YouTube Video)

- Nervous System Basic Outline (Web Image)

- Peripheral and Central Nervous System (Web Image)

- Parasympathetic vs. Sympathetic Nervous System (Web Image)

- Neuron Structures (Web Image)

- Neurotransmitters

Chapter 4: States of Consciousness

- Crash Course Psychology #9 (Sleep) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #10 (Altered States) (YouTube Video)

- Oxford Sparks: Circadian Rhythms (YouTube Video)

- Ted Talk: Circadian Rhythms and Health (YouTube Video)

- Khan Academy: Sleep Stages and Circadian Rhythms (YouTube Video)

- Sleep Cycle Infographic (Web Image)

- Effects of Insomnia on the Body (Web Image)

- Dreaming Comic (Web Image)

Chapter 5: Sensation and Perception

- Crash Course Psychology #5 (Sensation & Perception) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #7 (Perception) (YouTube Video)

- TedX Education: Synesthesia (YouTube Video)

- TedX Education: How You See Color (YouTube Video)

- Khan Academy: Visual Cues, Monocular vs. Binocular, Constancies (YouTube Video)

- Psychology Vidcast: Subliminal Messages (YouTube Video)

- Sensation vs. Perception (Web Image)

- Gestalt Principles Summary (Web Image)

- Gestalt Principles (Web Image)

- Sensation and Perception (YouTube Video)

Chapter 6: Learning

- Crash Course Psychology #11 (Conditioning) (YouTube Video)

- TedX Education: Classical/Operant Conditioning (YouTube Video)

- Classical Conditioning (Web Image)

- Operant Conditioning (Web Image)

- Operant vs. Classical Basic Comparison (Web Image)

- Operant vs. Classical more detailed Comparison (Web Image)

Chapter 7: Thinking and Intelligence

- Crash Course Psychology #23 (Intelligence Testing/Controversy) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #24 (Brains vs. Bias) (YouTube Video)

- TedX: The Optimism Bias (YouTube Video)

- Ted Talk: Dan Gilbert on Why We Make Bad Decisions (Web Video)

- Khan Academy: Theories of Intelligence (YouTube Video)

- Ted Talk: The Intelligence of Crows (Web Video)

- Koko the Gorilla (YouTube Video)

- Alex the Parrot (YouTube Video)

- Elements of Cognition (Web Image)

- Cognitive Bias Images (Web Image)

Chapter 8: Memory

- Crash Course Psychology #13 (Making Memories) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #14 (Remembering & Forgetting) (YouTube Video)

- Ted Talk: False Memories (YouTube Video)

- False Memory Test (YouTube Video)

- Ted Talk: How your working memory helps you make sense of the world (YouTube Video)

- Khan Academy: Information Processing Model (YouTube Video)

- BioEd Online: Learning and Memory Overview (YouTube Video)

- Ted Ed: How memories are formed and how we lose them (YouTube Video)

- Henry Molaison (H.M.) (Web Image)

- Information Processing Model of Memory (Web Image)

- Organization of Long Term Memory (Web Image)

- Types of Long Term Memory (Web Image)

- Types of Long Term Memory (simple diagram) (Web Image)

- Areas of the Brain Involved in Memory (Web Image)

- Storage (YouTube Video)

Chapter 9: Lifespan Development

- Crash Course Psychology #18 (The Growth of Knowledge) (YouTube Video)

- Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development (Web Image)

Chapter 10: Emotion and Motivation

- Exploring Facial Expressions with Paul Ekman (YouTube Video)

- Ted Talk: How to Spot a Liar (Web Video)

- Ted Talk: Lie Detection (YouTube Video)

- Self-Efficacy (YouTube Video)

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (YouTube Video)

- Abraham Maslow (Course Module)

- Crash Course Psychology #17 (The Power of Motivation) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #26 (Emotion, Stress, and Health) (YouTube Video)

- The Psychology of Motivation and Emotion longer one, not for class (very detailed) (YouTube Video)

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (Web Image)

Chapter 11: Personality

- Crash Course Psychology #22 (Measuring Personality) (YouTube Video)

- Personality Theories Overview: Eight Major Approaches (YouTube Video)

- Khan Academy: Psychoanalytic Theory of Personality (YouTube Video)

- Khan Academy: Freud’s Psychosexual Stages in Depth (YouTube Video)

- Khan Academy: Humanistic Approaches to Personality (YouTube Video)

- The Big 5 Personality Traits (YouTube Video)

- Cultural Dimension: “Me” or “We” (YouTube Video)

- Freud’s Psychosexual Stages (Web Image)

Chapter 12: Social Psychology

- Crash Course Psychology #37 (Social Thinking/Cognitive Dissonance) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #38 (Social Influence) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #39 (Prejudice/Discrimination) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #40 (Aggression/Altruism) (YouTube Video)

- Khan Academy: Conformity and Groupthink (YouTube Video)

- TedX: Stories of Implicit Bias (YouTube Video)

- Stanley Milgram (Web Image)

- Milgram Shock Generator Control Panel (Web Image)

- Stanford Prison Study Newspaper Ad (Web Image)

- Stanford Prison Study, Prisoner with Guard (Web Image)

- Phillip Zimbardo (Web Image)

- Ethnic Identity Comic (Web Image)

Chapter 13: Industrial-Organizational Psychology

- Ten Minute I/O Psychology (YouTube Video)

- Motivation Theories and Principles (YouTube Video)

- I/O psychology (Web Image)

Chapter 14: Stress, Lifestyle and Health

- Crash Course Psychology #26 (Emotions/Stress/Health) (YouTube Video)

- Ted Talk: How Stress Affects Your Brain (YouTube Video)

- Robert Sapolsky: Stress Response: Savior to Killer (YouTube Video)

- General Adaptation Syndrome (Web Image)

- Stress in the Brain and Body (Web Image)

- Psychology of Happiness (YouTube Video)

Chapter 15: Psychological Disorders

- Crash Course Psychology #28 (Psychological Disorders) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #29 (OCD, Anxiety Disorders) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #30 (Depressive & Bipolar Disorders) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #31 (Trauma and Addiction) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #32 (Schizophrenia, Dissociative Disorders) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #34 (Personality Disorders) (YouTube Video)

- Intro to the DSM (YouTube Video)

- TedX: Challenges and Rewards of a Culturally-informed Approach to Mental Health (YouTube Video)

- Ted Ed: Debunking the Myths of OCD (YouTube Video)

- The VisualMD: What is Depression? (Web Video)

- Auditory Hallucinations: An Audio Presentation (YouTube Video)

- Simulation of the Experience of Schizophrenia (YouTube Video)

- Ted Talk: Why Everything You Know About Addiction is Wrong (YouTube Video)

- Ted Talk: The Power of Addiction (YouTube Video)

- Ted Talk: The Voices in My Head (schizophrenia) (YouTube Video)

- Ted Talk: A Tale of Mental Illness (schizophrenia) (YouTube Video)

- Ted Talk: Mental Disorders as Brain Disorders (YouTube Video)

- DSM-V Anxiety Disorders (Web Image)

- Depressive and Bipolar Disorder (YouTube Video)

Chapter 16: Psychological Disorders

- Crash Course Psychology #35 (Getting Help) (YouTube Video)

- Crash Course Psychology #36 (Biomedical Treatments) (YouTube Video)

- What is psychodynamic therapy? (YouTube Video)

- Psychodynamic Therapy Role-Play (YouTube Video)

- What is Psychoanalysis? (YouTube Video)

- How Weed Works? (YouTube Video)

APPENDIX D

Timeline For Adopting the OpenStax General Psychology Textbook

| Semester |

Task |

|---|---|

|

Spring 2017 |

|

|

Summer 2017 |

|

|

Fall 2017 |

|

|

Spring 2018 |

|

|

Fall 2018 |

|

|

Spring 2019 |

|

APPENDIX E

Dr. Schell’s Course Goals as Stated in his Syllabus for General Psychology

QUINTESSENTIAL COURSE GOALS:

There are three quintessential objectives of the course:

- To master knowledge of psychology at the introductory level

- To think like a psychologist

- To ask fundamental, heuristic, and intriguing (e.g. Socratic) questions.

OBJECTIVES REFLECTING THE ELEMENTS OF REASONING:

A good critical thinker in general psychology employs the elements of reasoning in a systematic way that allows the fullest breadth and depth in thinking. The elements of reasoning are reflected both in the logic of science and in the logic of general psychology. They include:

- Key Question: How can the science of psychology help us describe, predict, control/change, and explain human behavior and mental processes?

- Interpretation and Inference: Students will learn how psychologists gather and interpret data and apply same to the issues studied in the course.

- Information: Students will learn the benefits and limitations of the scientific method and theory in describing, predicting, controlling/changing, and explaining human functioning and adaptation.

- Essential Concepts: Students will learn basic concepts (e.g. operant conditioning, synaptic transmission, intelligence quotient, etc.) and theories (e.g. psychodynamic, behaviorism, etc.) that underlie the psychological understanding of human behavior and mental processes.

- Assumptions: The fundamental assumption of this course is: there are intelligible and discoverable reasons why humans behave, think, and feel the way they do.

- Implications and Consequences: Students who reason well about psychology should be able to better understand their own behavior, thinking, and emotions as well as better understand the behavior, thinking, and emotions of others.

- Points of View: Students will learn how to reason using data derived from the scientific method (i.e. careful observation and systematic study) and to analyze and evaluate human behavior and mental processes through the lens of six major psychological perspectives (theoretical orientations): (1) biopsychological, (2) learning/behavioral, (3) cognitive, (4) socio-cultural (5) psychodynamic, and (6) humanistic/existential.

OBJECTIVES REFLECTING THE INTELLECTUAL STANDARDS:

In order to accomplish the broader objectives, you need to:

- Describe accurately, clearly, and precisely basic terms, concepts, theories, research, and relevant issues in psychology today.

- Analyze, evaluate, and apply the above to human functioning and adaptation AND to issues of diversity and technology.

- Apply good critical thinking (See “Critical Thinking in Psychology”) to the concepts, theories, and knowledge bases in psychology.

- Excel in a learning environment that respects the cultural, individual, and role differences, including those due to age, gender, race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, disability, language, and socioeconomic status of members of the class.

- Engage in a course pedagogy that will include lecture, discussion, demonstrations, and Socratic questioning.

OBJECTIVES REFLECTING BLOOM’S TAXONOMY:

The learning objectives are specified via Bloom’s (1956) Taxonomy:

|

Cognitive Skill |

Specific Examples |

|

Knowledge |

recall, define, match, name, list, outline, observe, record |

|

Comprehension |

recognize, locate, identify, summarize, report, explain |

|

Application |

solve, demonstrate, organized, illustrate, research |

|

Analyze |

classify, relate to, map, compare/contrast, infer, refute, interpret |

|

Synthesize |

construct, create, plan design, speculate |

|

Evaluate |

prioritize, persuade, assess, predict, criticize |

More specifically, what is it that you should know and be able to do at the end of the semester? In other words what would distinguish you, who have taken the course, from a student who did not take the course? The answers to these questions are set forth in the following specific objectives:

- Objective 1: As a result of taking this course you will be able to recall, recognize, identify and define basic terms, concepts, theories, research, and relevant issues in psychology [assessed via exams (graded), chapter quizzes (graded) and in-class dialogue (non-graded)].

- Objective 2: As a result of taking this course, you will be able to explain, analyze, evaluate, and synthesize the various psychological concepts and theories pertaining to human functioning and adaptation and to issues of diversity and technology [assessed via exams (graded), chapter quizzes (graded), in-class dialogue (non-graded).

- Objective 3: As a result of taking this course, you will be able to compare and contrast the major perspectives and interpret the research reflecting the efficacy of psychological concepts. [assessed via exams (graded), chapter quizzes (graded), in-class dialogue (non-graded).

- Objective 4: As a result of taking this course, you will be able to apply cases to illustrate psychological concepts [assessed via exams (graded)].

RATIONALE OF COURSE OBJECTIVES:

The American Psychological Association (American Psychologist, 2007, pp 650 to 669) published an article entitled, “Quality Benchmarks in Undergraduate Psychology Programs.” The article stipulates that all courses in psychology should be grounded in the scientific foundation of the discipline and strive for the following student learning outcomes: (1) writing skills, (2) speaking skills, (3) research skills, (4) collaborative skills, and (5) information literacy and technology skills. To that end the Psychology Department developed the following mission statement for the undergraduate curriculum: “The overarching goal of the undergraduate program in Psychology is to introduce students to current theories, research, and methodologies within the field. Through a variety of courses, at the introductory level and then in advanced seminars, students learn to understand and explain how humans function behaviorally, cognitively, emotional, and socially. They also learn to analyze and evaluate the many factors that influence human functioning and how the human mind integrates these factors in shaping an individual’s adaptation to the environment. Students receive scientific training through courses on research design and methodology, and these methods are incorporated within courses throughout the curriculum. Courses are also designed to stimulate critical and analytic thinking, and to foster effective communication skills. At the undergraduate level the department outlined the following student learning goals: knowledge and comprehension of theories and basic research in the major domains of psychology; knowledge of quantitative and research methods in psychology; acquisition of critical thinking skills; and acquisition of effective communication skills.”

- Bidwell, A. (2014). Report: High Textbook Prices Have College Students Struggling. US News and World Report. https://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2014/01/28/report-high-textbook-prices-have-college-students-struggling ↵

- SPARC Open Educational Resources page ↵

- Feldstein, A., Martin, M., Hudson, A., Warren, K., Hilton III, J., & Wiley, D. 2012. Open Textbooks and Increased Student Access and Outcomes. European Journal of Open, Distance, and E-Learning. ↵