5.2. Over-the-Arrow Notation in Chemical Reactions

When showing either reaction equations or mechanisms additional information is sometimes provided. This is done is to add detail to the reaction without needing to write a paragraph to accompany the equation. The information is added above (and below) the reaction arrow connecting the starting material(s) and product(s) (Figure 5.3). We refer to this shorthand as “over-the-arrow” notation.

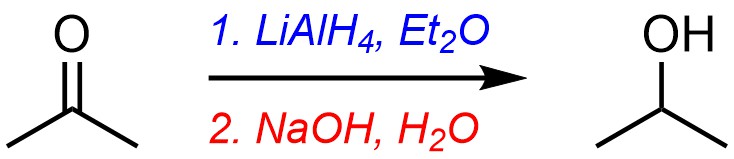

Figure 5.3 – Simple Example of Over-the-Arrow Notation.

Technically there are no codified rules for how this is done or what information is included/excluded. However, most sources use a similar approach.

5.2.1. Commonly Shown Species and Conditions

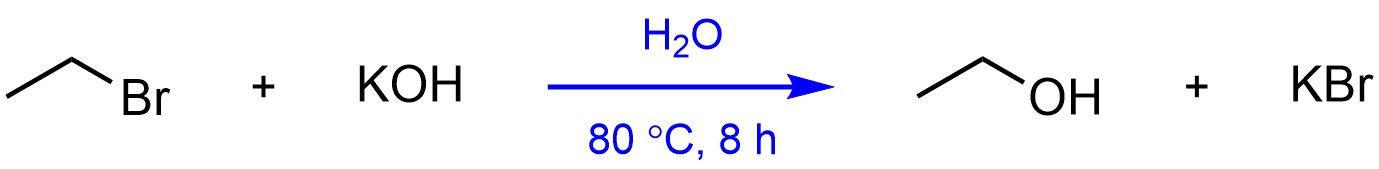

Over-the-arrow notation can be used to convey as much or as little information as desired (Figure 5.4). In very detailed cases all the information needed to repeat the reaction might be included. Commonly included information comprises reactants, reagents, and/or catalysts, their relative amounts (as equivalents to the starting materials), solvents, the concentration of the reaction, the temperature of the reaction, and the length of time needed for the reaction to occur.

Figure 5.4 – Common Convention for Over-the-Arrow Notation with an Example.

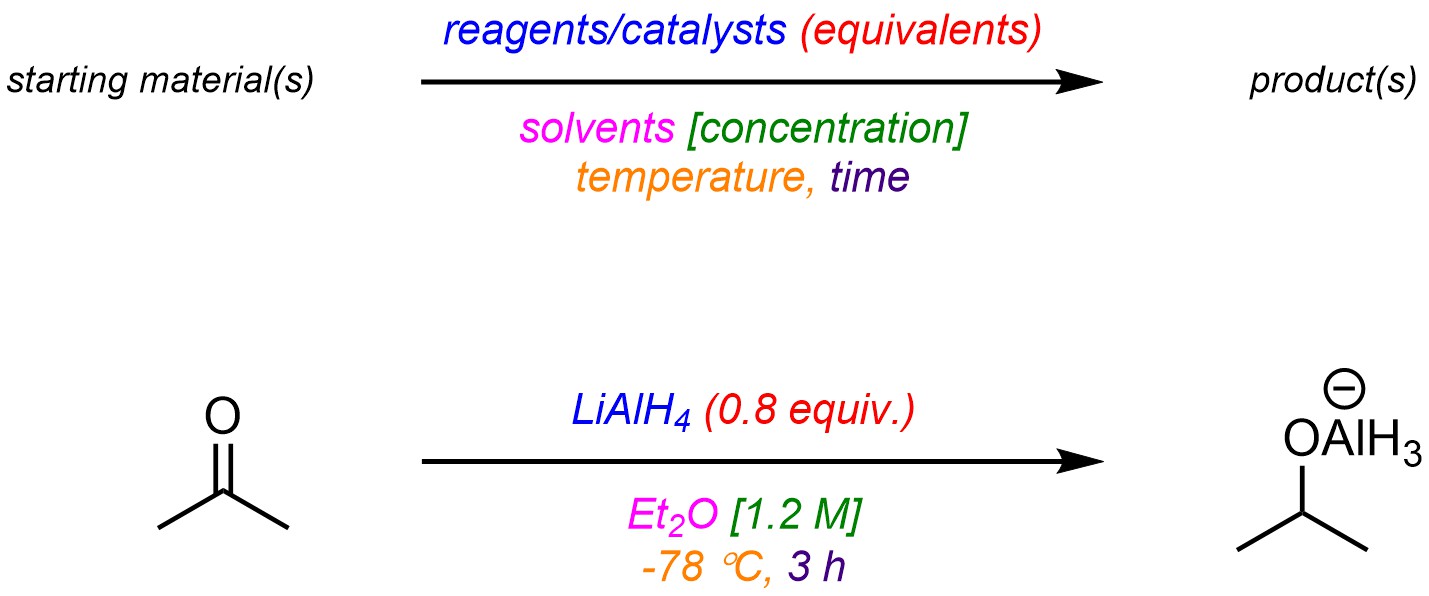

Usually less information is included, with only the key parts written to highlight what is happening and any special conditions required (Figure 5.5). For example, the solvent and temperature are important for this reaction (it will probably not work well if other solvents or temperatures are used) but the exact equivalents of the reagent and concentration are not (it will probably work well even if these are significantly adjusted).

Figure 5.5 – Example of Simplified Convention for Over-the-Arrow Notation.

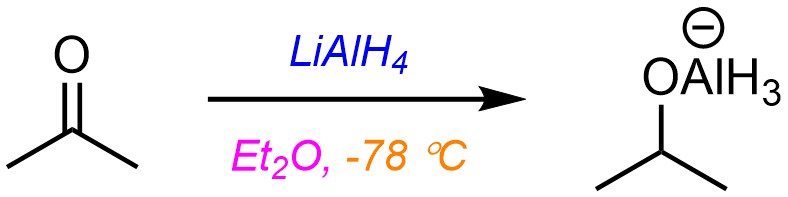

Remember that there is technically no requirement to be consistent with where or what information is added. This means that some sources might not include some information (even if it is “important”), or place it in a different order/location, or change the style between different figures in the same document (Figure 5.6). It is important to be able to read and interpret what information is included and understand how it might (or might not) be important for understanding the reaction.

Figure 5.6 – Examples of Different Possible Over-the-Arrow Notations.

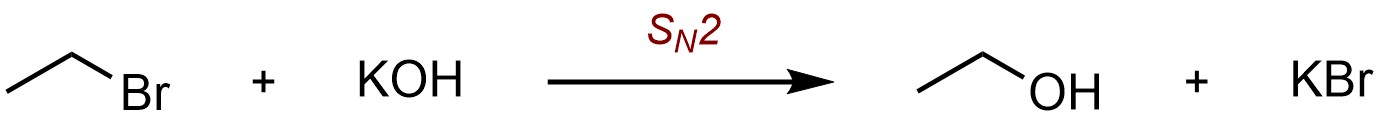

In some cases other information might be included. Usually this is meant to guide the reader, such as a label for the type of reaction or mechanism that will be followed (Figure 5.7). Often this is done when more than one reaction/mechanism is possible.

Figure 5.7 – Other Information in Over-the-Arrow Notation.

5.2.2. Reactions with Multiple Steps

Sometimes converting a starting material into a certain product takes more than one step, with multiple reaction conditions. Each step can be written out as a separate reaction equation. However, it is more convenient to avoid re-drawing things. There are two common ways to show the overall transformation.

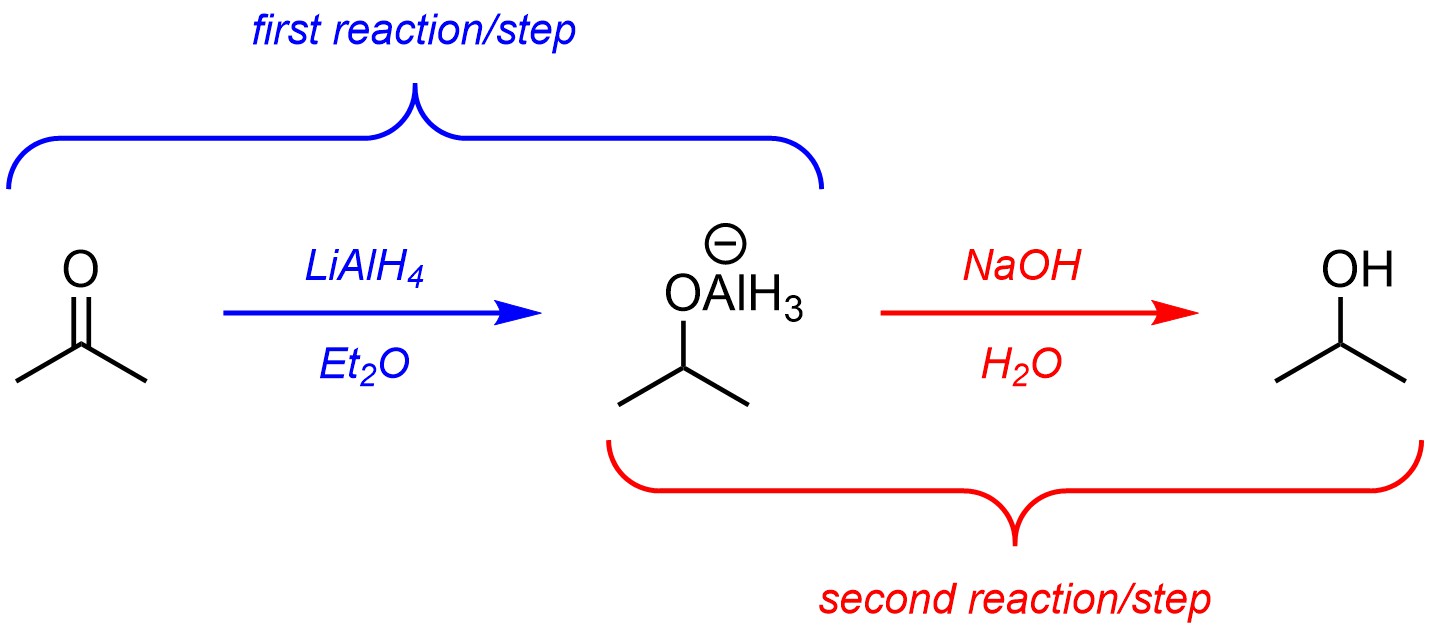

One approach is to discretely draw out each step’s product and use that as the starting material for another reaction equation (Figure 5.8). Since these are sequential reactions, the first step must be complete before the second step can happen. This works better for teaching materials as it allows the reader to directly see what the exact product is for each step. However, this approach is not commonly used in research or academic papers because it implies that the product of the first step is isolated (taken out of the reaction vessel, dried, and purified), which is often not correct.

Figure 5.8 – Example of Multiple Steps as Discrete Steps.

The other approach is to include details from the sequential steps above and/or below a single arrow connecting the starting material(s) and the overall product(s) (Figure 5.9). The different steps are numbered to indicate they are not all occurring at once. Instead of discretely drawing the product of the first reaction, it is implied that whatever product is made is used directly as the starting material for the second reaction. This approach works better for formal or advanced texts as it requires the reader to already understand and visualize what the product is for each step. This also makes it useful for examination purposes.